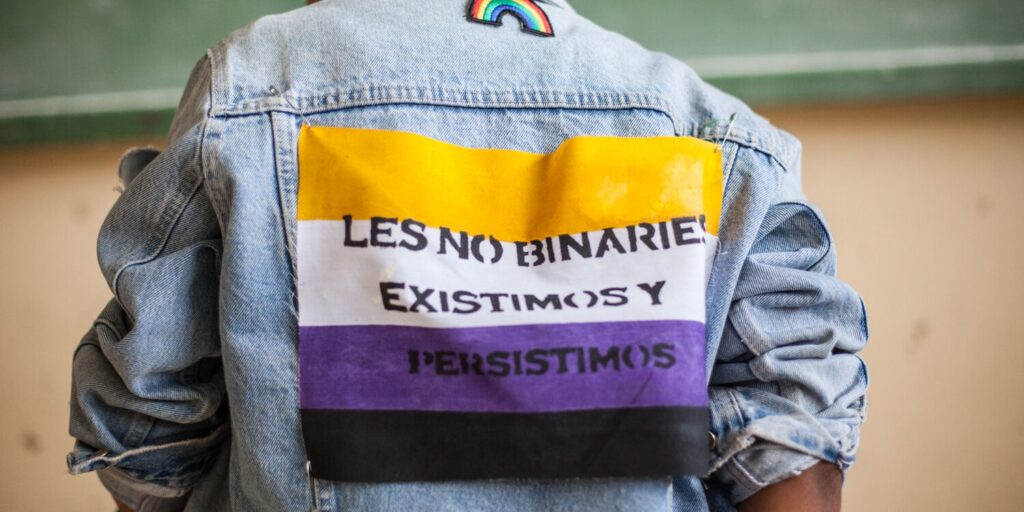

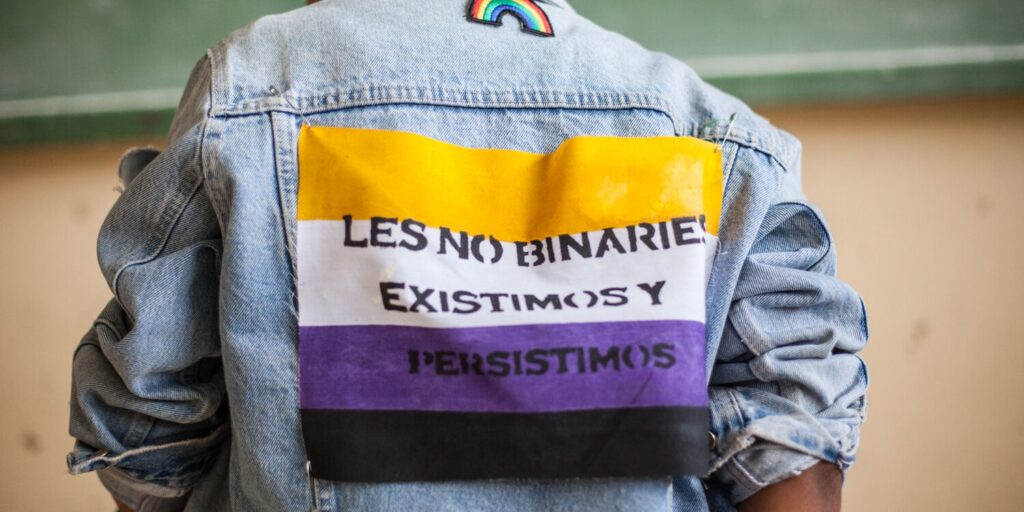

How does a non-binary person with a rectified document live: in limbo

Although 18 Mexican states allow for the rectification of identity documents, non-binary people who do so face invisibility and bureaucratic hurdles. In this investigation, non-binary people share their firsthand experiences of the process.

Share

What happens after a non-binary person (also known as NB) corrects their birth certificate in Mexico? What are the risks and obstacles involved in validating identity documents and records?

After years of activism, it is now possible to correct identity documents in 18 Mexican states. However, in practice, it remains a real feat that discourages other non-binary people. How do non-binary people struggle and resist adapting to a changing legal framework, the discretion of officials, and broken promises of full recognition?

A bureaucratic odyssey

As if it were a metaphor for her entire process, K realized she was invisible on the form she had to fill out at the Civil Registry. In the "sex" section, only the options M and F—male and female—were included. There was no third option anywhere. With the same pen she had used moments before to write her new registered name, she drew a circle next to the two options and added a third: NB.

The idea of changing her identity documents came to her suddenly, after a violent experience. From then on, she began to investigate. In Mexico City, where she lives, the process seemed simple, and although she expected some red tape, she never imagined that she was about to embark on a bureaucratic odyssey that would take her more than two years to complete.

A group advised her and told her what documents she would need to take to the Civil Registry. K explained what she needed multiple times without much success until a bureaucrat finally understood the procedure she was referring to. There, they gave her the form, which she filled out by hand so that the State could recognize her identity.

After decades of statistical silence, in 2021 we gained a rough idea of how many people identify as non-binary in Mexico. That year saw the ENDISEG 2021 , the first national survey on the gender and sexual diversity population, which included the T+ population: queer, agender, gender-fluid, non-binary people , among others. According to the survey, the number of people aged 15 and over who identify within T+ identities was 900,000 nationwide.

With this survey, the Williams Institute and YAAJ conducted a study that counts at least 340,000 Mexicans who identify as non-binary. However, this is far from an accurate count. A more robust survey is needed that includes the multiple ways in which non-binary people identify themselves, as well as the difficulties, violence, precariousness, and rights restrictions they face.

In Mexico, the LGBT+ community continues to face greater challenges in accessing their rights than the rest of the population . While 23% of the general population reports having experienced discrimination in the last 12 months, 37% of the LGBT+ population has experienced it ( ENADIS, 2022 ). This has multiple effects on mental health: 28.7% of LGBT+ people over the age of 15 have had suicidal thoughts or attempted suicide, three times more than the general population (ENDISEG, 2021).

Identity documents do not, in themselves, guarantee the full exercise of basic rights. However, some of them, such as voter registration cards, can serve as a defense against discriminatory acts, especially in public spaces considered exclusive (gyms, restrooms, public transportation, for example).

B comments that, in the face of discrimination or violence, legal recognition can help protect, because it serves to reaffirm gender identity. The document acts as a device for reaffirming one's identity and can guarantee its respect and recognition. But this does not always happen.

For the legal and identity system, the gender binary has been one of the organizing structures: from birth to death, gender categories are included that construct, reproduce, and shape gender roles and their social function. Adapting this administrative and legal architecture to the reality of non-binary people is an immense challenge for the Mexican State.

While these sex/gender indicators might seem merely a superficial element for identifying each citizen, for philosopher Judith Butler they are a central axis of social organization and the State ( Who's Afraid of Gender , 2024). For her, sex and gender operate as legal and social identifiers that sustain a legal-epistemic apparatus aimed at tautologically reaffirming gender roles and, with them, the division of labor and the organization of basic rights .

When these categories are challenged, Butler says, it becomes clear that they constitute one of the main mechanisms of regulation and control over our bodies and identities.

Guanajuato, a pioneer in recognizing a non-binary person

In February 2022 , Guanajuato became the first state to recognize the legal gender change for a non-binary person. This was achieved after a court ruling that compelled one of the country's most conservative states to recognize these identities. Since then, 18 other states have amended their constitutions and laws to allow anyone to correct their birth certificate through an administrative process.

This, however, has not been accompanied by regulations that would allow for a more expedited standardization of identity documents at the subnational level. The absence of standardization protocols, coupled with a lack of awareness among administrative staff, negatively impacts the development and well-being of non-national individuals.

In a legal limbo

“In theory, I have three CURPs,” C tells me. When she went through the process of changing her identity, her birth certificate had to be corrected twice. First, the Civil Registry staff incorrectly changed her gender; then, they did the same with her name. However, the error wasn't detected until the change to the CURP was processed.

C lives in a legal limbo that prevents him from looking for work, opening a bank account, or obtaining a driver's license. This also prevents him from obtaining a voter registration card or passport. In practical terms, his daily life and the full exercise of his rights are on hold.

C's testimony illustrates how non-binary people live an intermittent life in the eyes of the state. Legislative advances do not mean that procedures have been streamlined, nor that there is training for the bureaucratic apparatus. Even less so that, in three and a half years, computer systems have been modified to "allow" the digital existence of people who have begun their legal transition processes.

What began in 2022 in some states as a procedure that would "resolve" the recognition of non-binary identities, has now become a legal, social and juridical limbo for thousands of NB people, who for various reasons prefer not to do it in the country.

“I began my legal transition after a hate crime by a ride-hailing driver,” K, a non-binary person from Mexico City, tells me. “I didn’t want to die and be buried under another name.”

“I would like to, but I know it’s so difficult and limits so many processes, that I don’t want to put myself in a vulnerable situation,” B tells me.

“I started and from that first day it’s been nothing but trouble,” says C.

A single procedure, however, cannot resolve or guarantee the full recognition of non-binary people's existence. If gender is a basis for population organization, a deeper restructuring of that same binary and exclusionary state system is necessary.

This is also reflected in the private sphere: the invisibility of non-binary people by the State legitimizes and justifies the restrictions and limitations of private institutions, such as schools, banks or workplaces.

K had to sue UNAM to have her legal transition recognized on her academic transcripts. Now, she also advises other non-binary individuals who have been rejected from the admissions process because their CURP (Mexican national ID number) with an "X" marker is not accepted by UNAM's digital system.

The lack of comprehensive legal recognition is not only a problem of bureaucratic procedures, but an impossibility of having a fuller life.

Carrying out any procedure if you are a non-binary person who has already corrected their birth certificate is a risk and a drain that shouldn't be, R tells me. From staff who don't know that the non-binary CURP exists and fear facing consequences for allowing the change, to institutional discrimination, so common in banks and universities, she says.

According to the National Diagnosis on Discrimination against LGBTI People in Mexico (2018), 66% of LGBT+ people surveyed reported aggression, harassment and/or violence because of their identity or sexual orientation in their educational spaces.

Organizing and lobbying politicians and officials also achieves some progress. R and B, who work with non-binary groups, talk about the numerous meetings, gatherings, and conversations they have with authorities: directors, deputy directors, and managers of public institutions. All of this so that R could make adjustments to their bank account as part of a pilot program they joined. B is in talks with federal deputies to push for a constitutional reform that would include gender identity and expression in Article 1 of the Constitution.

But this does not mean that correcting documents is an achievable process for most of the population. NB: “ I wouldn’t have been able to make all the changes I’ve been able to make on my own, without the pressure and support of the collectives,” R tells me.

R also explains that health institutions, such as the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) and the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), continue to ignore requests from agencies like the National Population and Identity Registry (RENAPO) and the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (CONAPRED) to implement mechanisms that would allow non-binary people (NB) to correct their documents and records. The State is a multi-headed beast that moves at different times and, at times, in opposite directions.

Beyond the documents?

But even if full document standardization could be achieved through reforms and protocols, this in itself does not generate immediate changes in society.

Gender-neutral identification, whether marked with an X or an NB, forces individuals to relinquish the security of not revealing their gender identity to potential employers, authorities, or even family members. “Being in the closet hurts, but so do rejection and violence,” JC tells me. At work, they present as male, and their colleagues respect that identity. However, they doubt they would receive the same acceptance if they had to explain their non-binary identity.

She works as a lawyer and identifies as femme. She finds it amusing to see the reactions of her colleagues in law firms and courts, but she also tells me that she is aware that starting the process of changing her documents would imply, at the very least, years of economic hardship, since her professional license—a central part of her practice—could not be corrected until much later in the homologation process.

In many cases, the advancement of legislation that attempts to guarantee non-binary identity was made without the support of collectives. Three years ago, when the push for non-binary documents began in the country, it was carried out through strategic litigation that ignored the criticisms and doubts that a large part of the non-binary community had regarding the X marker, as well as the vulnerability of being identified as a non-binary person in unsafe spaces.

Without secondary laws, protocols, or awareness and training guides, access to rights remains discretionary: non-binary people depend on the acceptance of a CURP (Unique Population Registry Code), a voter ID card, or a passport with an X marker. Something that, incidentally, would not happen with the documents of a cisgender person.

Furthermore, legal processes, such as document correction, exclude people who live outside the system's "normal" framework, such as people experiencing homelessness, migrants, or those working in unpaid labor (caregivers) or in the informal economy. Because of their gender identity, they lack access to their documents, as well as the necessary economic and social resources and time to obtain them.

This exclusion is not a legal loophole that can be addressed with "credentialing" campaigns. Beyond that, it raises questions like the one JC points out: if we don't have the conditions for everyone to have access to their rights and recognized identity, what should be the focus of our efforts?

Surviving amidst paperwork

Every trans person (binary or non-binary) develops personal survival mechanisms in contexts of high exclusion or in the face of a perceived violent response to their identity. While staying in the closet is one option (painful, but one that provides a certain degree of security, as JC mentioned), others fight for it through activism.

The authorities insist on closed-door meetings. They say that “if there aren’t enough people making these changes, there isn’t enough pressure to achieve them,” but activists like B, R, and K live a different reality. Their bodies, worn down by exhaustion and the strain of endless meetings, endure a thousand excuses, as well as the constant administrative and legal obstruction.

They, however, insist not on the responsibility of other non-binary people, but on the responsibility of the authorities to guarantee the right to full identity. “ We may be few, but even if we are only two people, we are already two citizens who do not have our rights ,” says K.

Like the vast majority of their generation, the non-binary people interviewed for this report experience daily burnout, with precarious, low-paying jobs and no benefits. They are also tired of the growing wave of transphobic attacks, hate speech disguised as debate, and the questioning of their rights.

Tired of the charade: of symbolic events and announcements from authorities that don't translate into any improvement in their daily lives. Tired, but not alone. They have support networks, friends who surround them, collectives that accompany and guide them to find work, to endure and resist together the most difficult days they have to face.

The non-binary community in Mexico may be very small, but it is not alone; it may not be counted by the State, but it has its own voice.

This report was produced with the support of the International Women's Media Foundation (IWMF) as part of its Express Yourself! initiative in Latin America.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.