Mexico: How gentrification affects access to housing for LGBT people

The advanced process of gentrification in Mexico directly threatens access to housing for LGBT people. The role of activism and the concern surrounding the upcoming 2026 FIFA World Cup.

Share

MEXICO CITY, Mexico. For two decades, Mexico has recognized rights for LGBT+ populations. These include, primarily, the right to marriage equality and, although not entirely, the recognition of gender identity. However, behind these advances and the official discourse of inclusion, the demand for the right to housing is intertwined with the phenomenon of gentrification.

Lawyer and housing rights advocate Carla Escoffié has insisted that gentrification “is not positive.” She also stated that it should be understood as a “preventable and reversible” process. She explained during an interview on journalist Julio Astillero's program.

Escoffié points out that gentrification is an expression of socioeconomic inequality. And that it is not a phenomenon of modernization but a process of displacement. “It is the process by which a neighborhood previously considered 'in decline' is revitalized by people from socioeconomic strata with greater purchasing power than its original inhabitants. The arrival of these new residents generates a change in consumption and living patterns that ends up displacing the original population,” he explains in this article published in Este País magazine .

These barriers are exacerbated for LGBT+ people and are particularly acute for those living in vulnerable conditions and experiencing family exclusion. Thus, gentrification and dispossession processes intersect with existing prejudices and barriers, multiplying their effects on these populations.

“In Mexico we don’t have a public housing policy, but rather a real estate policy.”

Attorney Escoffié previously explained to Presentes that in Mexico, housing is viewed as a market commodity, not as a right and a necessity. “The right to housing is not guaranteed. We don't have a public housing policy, but rather a real estate policy,” she said.

So how should we understand housing? For her, housing itself is the right to have a place to live. It includes the right to have measures in place to prevent forced evictions that are arbitrary, illegal, and unjustified; and even the right to non-discrimination in access to housing.

In 2022, the National Survey on Discrimination (ENADIS) indicated that 1 in 5 LGBT+ people had been denied some right in the last five years. Furthermore, it found that 1 in 3 people (33.4%) would not be willing to rent a room in their home to a transgender person .

This percentage decreases slightly when it comes to lesbian or gay people (29.8%) . There, the violence ranges from being denied housing, evictions, and harassment by neighbors, especially if they live with a partner or are trans, forcing them to move.

Covid-19 exacerbated the barriers to the right to housing

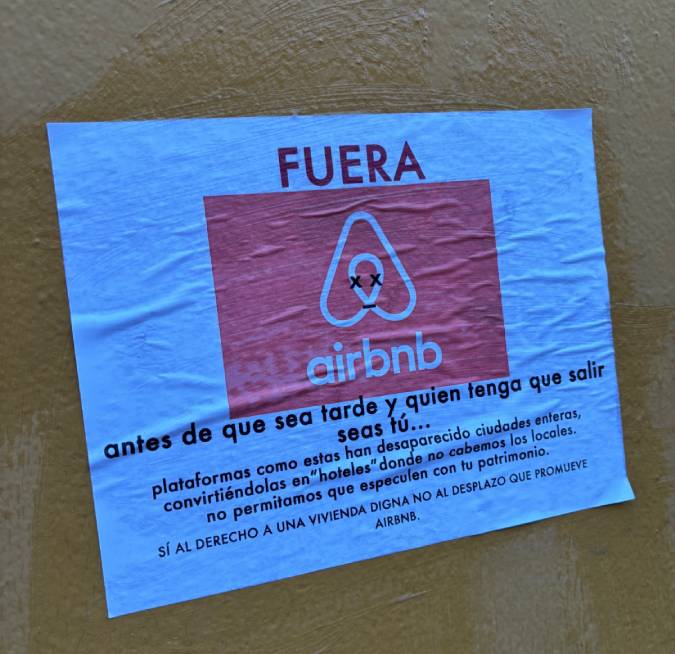

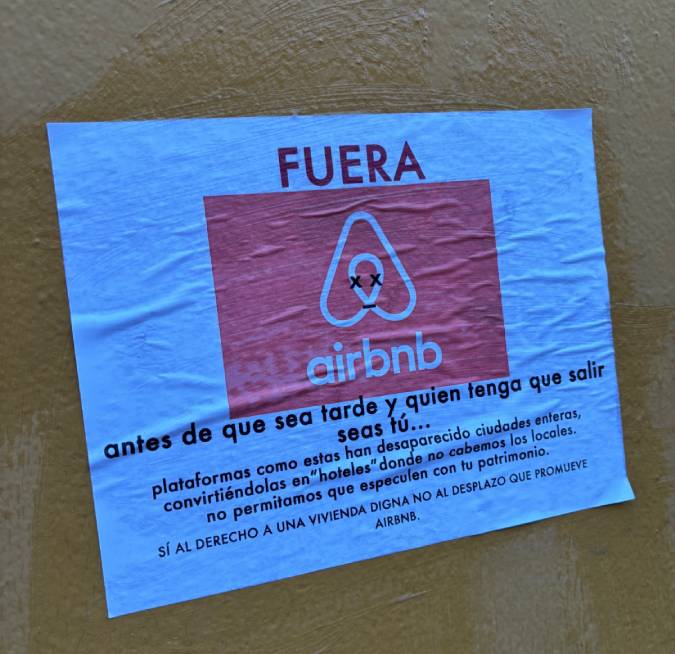

The phenomenon of gentrification in Mexico City gained greater impact after the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. The arrival of more digital nomads to the city caused a rise in rental prices, particularly in central areas, and a greater number of spaces dedicated to accommodations on platforms like Airbnb.

In the most vulnerable populations, one of the first consequences of the COVID-19 emergency was the closure of hotels. This left sex workers in Mexico City, especially trans women, without homes and places to work. According to the survey "Differentiated Impact of COVID-19 on the LGBT Community in Mexico ," 7 out of 10 people from the LGBTQ+ community lost their income, either partially or completely, with trans people being the most affected.

Similarly, 1 in 3 LGBT+ people could not afford their housing. 4.84% were forced to leave their homes due to domestic violence related to their sexual orientation and gender identity in the context of isolation.

The activism is a response to the lack of access to housing

In the face of the Covid-19 emergency, activists did the work of the State in addressing the violation of the right to housing of LGBT+ people in Mexico City.

An example of this was the activation of shelters such as Casa Frida , at that time mostly focused on migrant populations, and Casa Lleca, a shelter and community dining hall that is still active and today experiences the consequences of gentrification in the city.

“We can’t do this work alone; it’s up to the authorities. We mobilized to demand housing so that they don’t have to return to the shelter. We protested at the Ministry of Welfare and demanded the presence of the Housing Institute of Mexico City. Through this mobilization and the testimonies of our fellow activists, we reached an agreement to build housing for 42 trans people,” explained Victoria Sámano, founder of Lleca, listening to the street.

Authorities are expected to deliver those 42 homes within a year and a half. They are not free, and the Lleca shelter will also be relocated to Iztapalapa, a peripheral area in eastern Mexico City.

The impact of these actions on LGBT+ populations is not limited to moving further away. Leaving their current location can mean losing access to employment, increased expenses in money and time for transportation, reduced access to specialized health services, and fewer opportunities to exercise their right to the city. This, in turn, means less access to their community networks and emotional health support.

“We’re asking the government to relocate Casa Lleca to the city center. That’s where most of the homeless population lives, but they tell us there are no spaces available for rehabilitation. Their view is that the populations that bother them are better off living on the outskirts. There, they don’t bother the people who have access to these resources and live downtown,” Sámano explains.

In fact, none of the shelters for the homeless run by the Mexico City government are located in the city center. They are all located on the outskirts.

Increased vulnerabilities ahead of the 2026 World Cup

With the 2026 World Cup on the horizon, the head of government, Clara Brugada, has said that the event will allow "works and interventions that will remain forever and combat social inequalities."

Among them are the Tlalpan bike path that will connect the Zócalo with Azteca Stadium, and the Elevated Park, a pedestrian and bicycle promenade with green areas along the same avenue. Although presented as mobility and public space projects, organized sex workers have protested, fearing they will jeopardize their workplaces and safety. Tlalpan is one of the main hubs for sex work in the city.

According to La Jornada , “César Cravioto, the Secretary of Government of the capital, said that seven working groups have been held with sex workers where the use of different clothing for areas where schools are located has also been addressed, this at the request of parents.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

1 Comment