Belén, María Belén: Photobook about the founder of the Trans Memory Archive

Interview with María Belén Correa, one of the founders of the Argentine Transvestite Association, regarding the book that portrays her intimate and collective life, published by the Trans Memory Archive.

Share

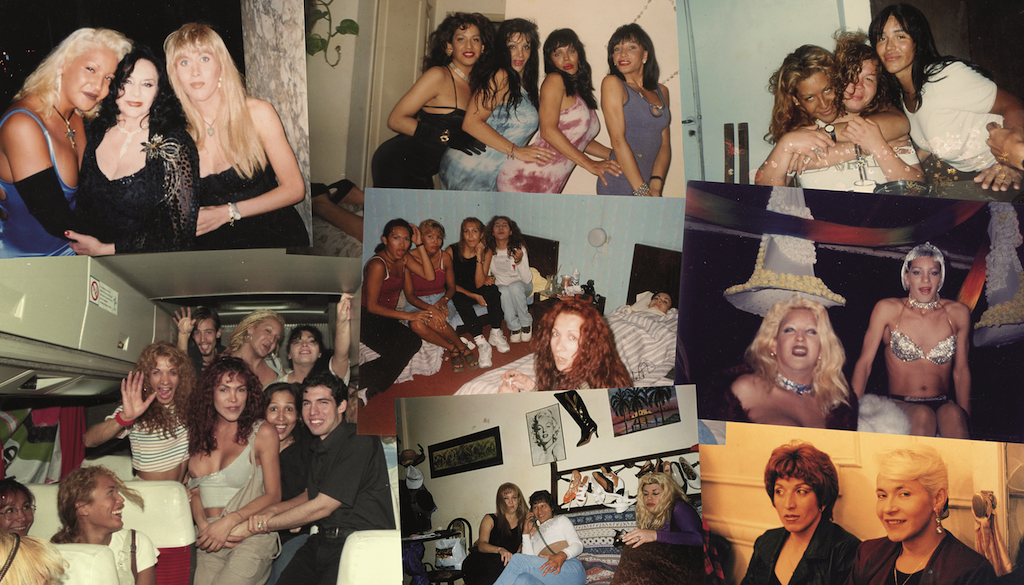

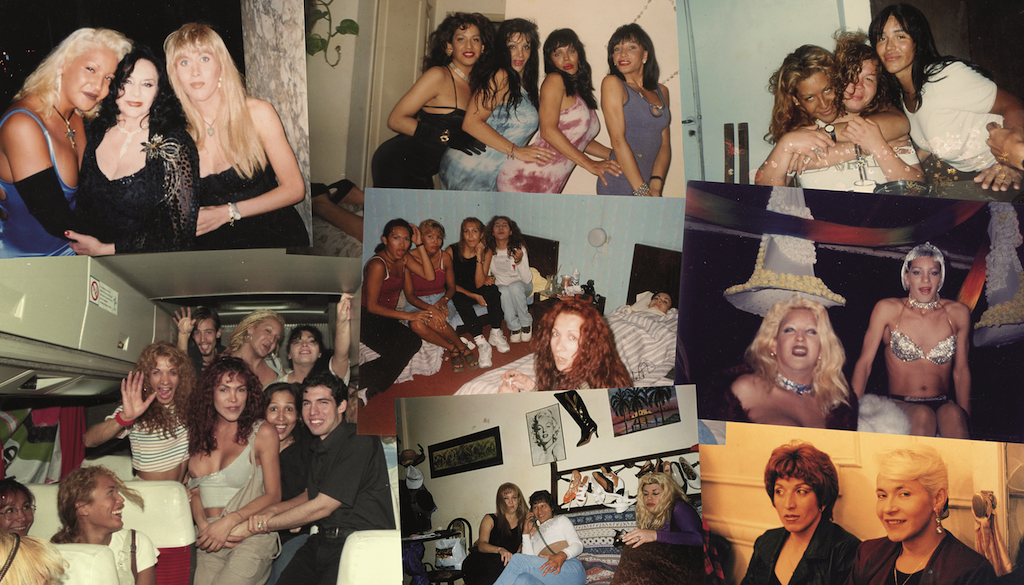

Letters, texts, pamphlets, photographs, and newspaper clippings reconstruct a moment in the intimate history of María Belén Correa: the formation of her identity and activism, her friendships, a note that changed everything, exile, and the figure who profoundly affected her: Eva Duarte de Perón. Belén, María Belén is the new photobook from Archivo Trans Publishing House , in collaboration with Cesura Publishing House. It portrays the life and legacy of this emblematic trans activist and one of the driving forces behind the Argentine Association of Transvestites (now ATTTA ) and the Lactrans Network, and founder of the Trans Memory Archive .

Today, some 18 people, including older trans women, are dedicated to protecting, building, and reclaiming trans memory through the Archive. Its collection now exceeds 15,000 documents: photographic, film, audio, and journalistic records; items such as ID cards, passports, letters, notes, police files, magazine articles, and personal diaries, dating from the early 20th century to the 1990s. In addition to making the documentary collections of several colleagues available online, the Archive has also published several books.

Belén was convinced that her new photobook should be about her own story, but she insists it's actually a collective creation. It was selected for the Andy Rocchelli managed by Cesura , and also received an honorable mention in the Dummy Award . She confesses that talking about herself feels strange. But she eventually manages it.

In Germany, where she lives, Belén spends her days with her mind on her home country. “My phone, computer, work, and television are all connected to Argentina. I’m 100% dedicated to the Archive,” she says in a phone call, sitting in her home in Hanover, where she lives with her husband and their two dogs, her children. She leads a monotonous daily life, without much of a social life. This is the opposite of what she experienced for much of her life: shows, demonstrations, police harassment and threats, sex work, and moving from country to country.

In 2015 and 2016, she suffered from meningitis in the cerebellum followed by tuberculosis. She almost died. “After that, I asked myself how I want to spend the last 10, 15, or 20 years of my life. And I want to be calm, without any surprises, doing what I love, which is partly collecting the Archive,” she says.

Around her neck she wears a pendant that belonged to her friend, the activist Claudia Pía Baudracco . During the conversations they shared in their youth, they imagined together a place to keep the memories and images of their companions, so that they wouldn't be lost during the raids and constant moves.

“At the time, I didn’t realize its importance. I did it because I enjoyed it. We wanted to document our family, which in our case were our friends. Pía was always taking photos or asking others for theirs and keeping them. Because of the moves, much of it was lost: whole boxes. But we found some that she had hidden in a friend’s house where she lived. Today it’s the Claudia Pía Baudracco Library in Quilmes,” Correa shares.

In 2012, just before the Gender Identity Law was passed, Pía died. She left a mark on Belén, who that same year decided to bring her dreams to life and founded the Trans Memory Archive from exile.

The Importance of Being Named Bethlehem

She was born on June 25, 1973, in the district of Luján, in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. She is 53 years old: a survivor from the trans community, whose average life expectancy is 35 to 40 years. She knows this all too well. Although she is at peace in her home in Europe, where she wants to spend the last stage of her life, she understands that violence against trans people transcends borders. “Just because I’m locked in my house doesn’t mean my husband won’t kill me tomorrow. You live with the enemy. No one is exempt,” she says.

She was five or six years old and playing under the table when she heard her grandfather say, "María Belén, what a lovely name." Later, she asked her family to name her unborn baby brother after her. But it was a boy: lifelong frustration and tears. "When my sisters, who are twins, were born, they granted my wish. One was named María Belén and the other María Vanina.".

She used to take the train to primary school in a neighboring town, Jáuregui, which was larger and more industrial. She lived with her parents, her brother, who was seven years her junior, and her twin sisters.

For ten years, in addition to being a daughter and student, she was a nurse, assistant, and cared for her siblings. The longest days were when her father had cancer. In 1989, when he passed away, she packed her things and traveled on the Sarmiento train to Buenos Aires.

“I arrived in Once and started walking along Pueyrredón Avenue, going from business to business. I didn't know anyone. Before reaching Santa Fe Avenue, I went into one of those old-fashioned strip clubs, they used to be cabarets. They asked me if I knew what it was. I said no, that I imagined it was a bar, that I could work as a dishwasher. They told me they only hired women. I said I was gay. They asked me my age. I was 16 and they couldn't hire me, but they gave me the address of a new agency that was looking for people. I stayed there.”.

In those early days in Buenos Aires, she went to her first birthday party, a big event with a show and a presentation. “I had thought of everything: dress, shoes, makeup, eyeshadow. Everything except my name. When I arrived, they greeted me and asked, ‘What’s your name?’ It took me by surprise. ‘Belén, María Belén…’ I said. Later, as much as I wanted to change it, I couldn’t because in the trans community, I was branded as María Belén. The only thing I could do was drop the María and have them call me Belén.”

“I felt like I was being educated alongside Pia”

At the agency, she met many transvestite and trans women. Those identities hadn't yet crossed her mind. She also didn't know that lesbians existed. “I got to know the different girls, the legendary ones, the ones who escaped from Panamericana. The agency was a place of rest for them because they weren't running from the police there. There were also girls who worked on the streets at night and in the agencies during the day. It became like a rotating schedule of girls. I started making friends. Among them were Pía (Baudracco) and Brigitte (Gorosito).”

With the help of her mother, with whom she maintains a close relationship to this day, she rented an apartment on Armenia Street in the Palermo neighborhood at the end of 1992 and left the agency. She soon ran into Pía on the street, and ten days later they were living together.

“Pía and I ended up becoming very close friends. Like any friendship, we went through all the stages: from living together to not being able to live together anymore. She was very sociable, too much so. You didn't have a house, you had a club that was always full of people. I would come home from working all night, and there would be people sleeping in my bed with my clothes. So we would end up fighting about these things. She was used to living like that, in a community,” Belén says.

They were of similar ages but had very different backgrounds. “She was three years older, but had been a transvestite since she was 13. She had been fighting with the police since she was 14, had been in a lot of jail cells, had gone to another country. She had an experience that I had never had. I felt like I was being educated alongside Pía .

From friends to founders of the Argentine Transvestite Association

Belén never liked celebrating her birthday, but a few months after they started living together, on July 25, 1993, Pía invited friends over to celebrate. They cooked and dressed up to welcome them. They arrived little by little, and as night fell, two of the girls were still missing. “They had been arrested. So we put together what we called a 'bagayo,' a bag with a blanket, cigarettes, and food, so they could get through the night. We put the same food from the birthday party in a Tupperware container. This changed the conversation. Of all of us there that day, the only one who knew freedom was Pía because she had traveled to Italy. We were talking about when she was going to take us there. And Pía said, 'No. We have to make the changes here so we're not always leaving.'” That day, along with other activists, they founded the Argentine Transvestite Association (now ATTTA), the first organization for the trans community in the country.

Organized, they began to denounce the police bribes. The department in Armenia gradually filled with people: between 50 and 60 trans women attended every Saturday to plan their next steps. They experienced at least two raids: the more people there were, the more they were targeted. “My photo was posted on the bulletin board at the Central Police Department for five years,” Belén shared in several articles.

“If I weren’t an activist, I wouldn’t be a transvestite.”

“For me, the world of activism was directly linked to being a transvestite. I didn't have a stage where I was first a trans woman or transvestite and then an activist: it was parallel. I understood it as the same thing: living in community, being an activist, wearing lipstick. I never had any other life than this. If I weren't an activist, I wouldn't be a transvestite ,” she explains today about how her identity was formed at that time.

She chose her mother's surname, Correa, and not Carlocchia, her father's. She says she did it for safety. “In the '90s, to protect ourselves, none of us used our real surnames so we wouldn't be identified so quickly: Berkins doesn't exist. Carlocchia, in Argentina, are the descendants of my great-grandparents: if I used that one, they could locate me instantly and raid my hometown.”.

Those pioneering Pride Marches, from the first one in 1992 until 1995, were protests, without shows or dancing. Belén's name began appearing in the newspapers in connection with complaints against the police and her presence at demonstrations. One day, she received a unique proposal. She was contacted by Para Ti to do a different kind of story. They wanted to tell the story of Belén the person , the one behind the struggle. She welcomed them into her home, introduced them to her mother and her town. They talked about her life, and took photos. Shortly after the article was published, the first threats began to arrive at her house.

“It was one of the biggest fights I ever had with my mom. She blamed me for everything that was happening. That's when I decided to leave and told my mom to start denying me: to say she didn't love me anymore, that she kicked me out, that I wasn't part of the family. For a long time, I would call the neighbor to talk to her. We don't talk about it now. She prefers it to be a thing of the past.”.

From the moment the threats arrived, she had 15 days to make the most important decision of her life. Just a month earlier, the world had been paralyzed by the images on television screens of one plane, then another, crashing into the North and South Towers of the World Trade Center. While many fled New York, terrified by the attack, Belén arrived in November 2001.

Exile in the United States

“My time in exile was the worst period of my life. The worst thing is leaving against your will. I left in 2001 and didn't return until 2008. In 2005, I was finally able to start traveling outside the United States. I would go to Uruguay to see my family. I couldn't cross into Argentina because I had political asylum. For many people, I was dead. I came back to life in 2008 when they saw me at the Pride March in Argentina,” she says.

She says it was hard to make a name for herself. Many times she thought she would receive help, but in the end, there was always an ulterior motive. She worked as a sex worker for the first few years and gradually gained visibility as an activist in the United States. She liked the term "trans"—which she still uses today—because "it didn't reveal whether someone had undergone surgery or not." She had to prove to a judge that she was neither gay nor lesbian, and explain what it meant to be trans in Argentina, where, even under a democratic system, they suffered persecution under police edicts.

For four years, she appeared before Immigration every four months without knowing if they would detain her, deport her, or let her go for a few more months until the next appointment. “You had to prepare yourself psychologically and say goodbye in case something happened every time you went,” she recalls.

Bethlehem and Evita

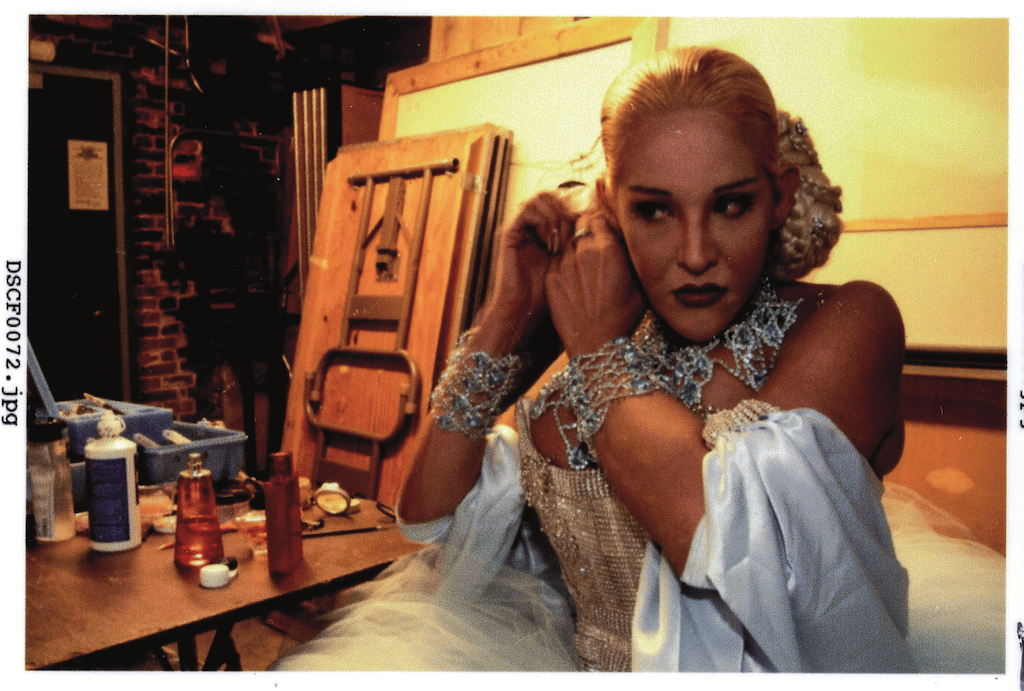

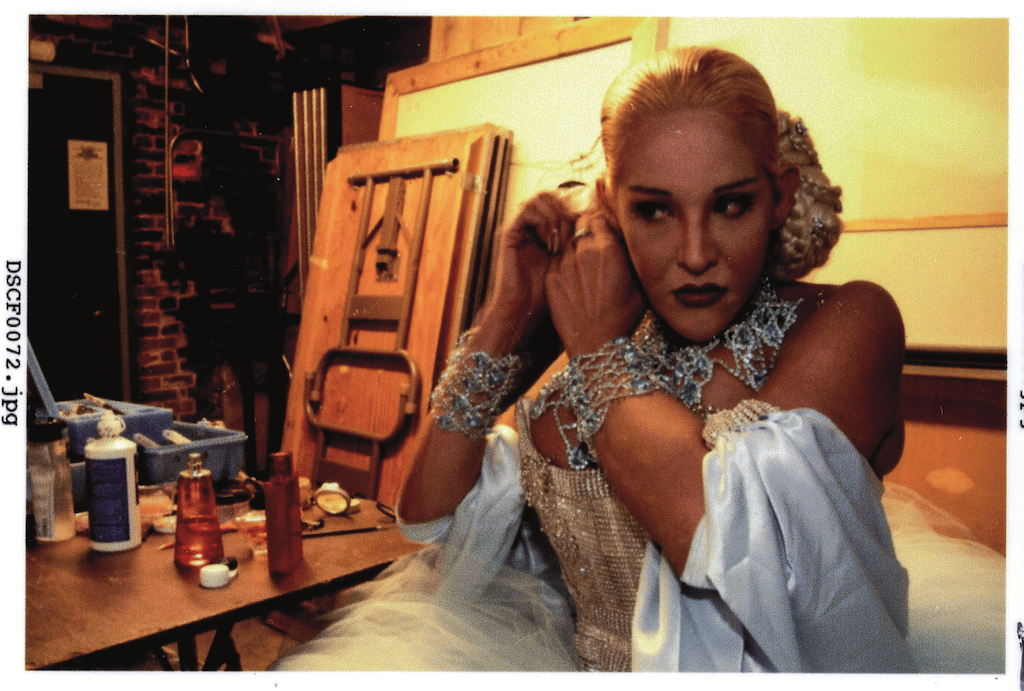

One night, at a social event for Latino migrants, she put on a show. She wore her blonde hair in a low bun, sparkly earrings, a large necklace with translucent white stones, and a white corset with silver appliqués. She sang “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.”.

“There weren’t any good experiences with transvestites or LGBT people playing Evita. There was the experience of Copi or Perlongher. One of them had her theater set on fire. Besides, you thought they were going to laugh their heads off. Peronism would come down hard on you for anything back then if you ‘insulted’ Eva. It was the time of Evita-mania.”.

The first time she embodied Eva Perón was at the request of her friend Vanesa. In 1993, transvestite birthday parties were social events, each featuring a performance. “Why don’t you do Evita for me?” her friend suggested. She took the character to the stage for the first time at the 1995 Pride March. Later, in the United States, she spent a whole year preparing for the Pride parade in Manhattan, where she performed under the name of the Argentine Transvestite Association. This hostile yet simultaneously favorable environment for Evita-mania allowed her to take the character to different countries. She arrived in Germany, precisely, “thanks to Eva.”.

Over the years, each time she portrayed Eva, she added a little something: a bracelet, a brooch. Today, she owns 36 books on Eva's biography, each exploring different aspects of her life. The book "The Eva Perón Case ," written by the embalmer Pedro Ara, was full of photographs of her alive, which he copied for his work. Belén adopted some of her mannerisms from these. She also cherishes " And Now… I Speak ," by Lillian Lagomarsino de Guardo , who accompanied Eva during the early years of Peronism and on her trip to Europe.

“In Europe they teach you how a queen greets people: slightly, inclining her head and moving her hand to show her rings. Physically, I could never see myself as Eva: big breasts, tall. The other one weighed 40 kilos and I weighed 80. But I always remembered something I was told, that in the theater, if you maintain the illusion and believe it, everyone else believes it too. So I copied all her gestures and movements,” Belén says.

Her family didn't have photos of Perón or Eva in their home, but Peronism had entered their lives in various ways. Her father's side of the family worked for the railways, and her grandfather was a member of La Fraternidad, a union historically linked to Peronism. Her mother was four years old when she received a doll from the Eva Perón Foundation , and her grandmother received a sewing machine from the same institution.

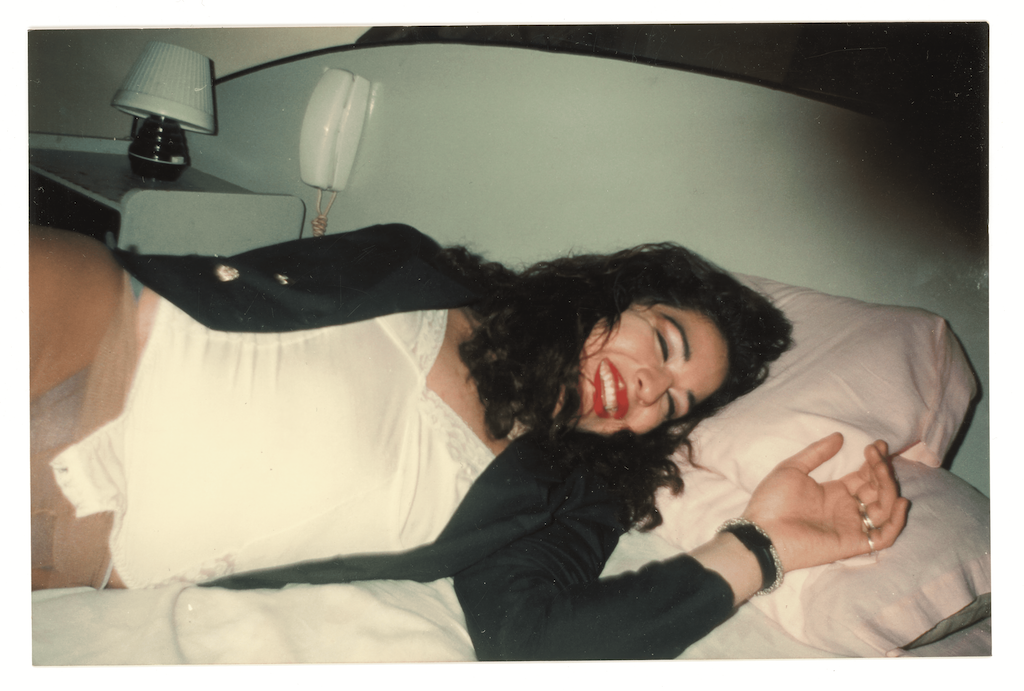

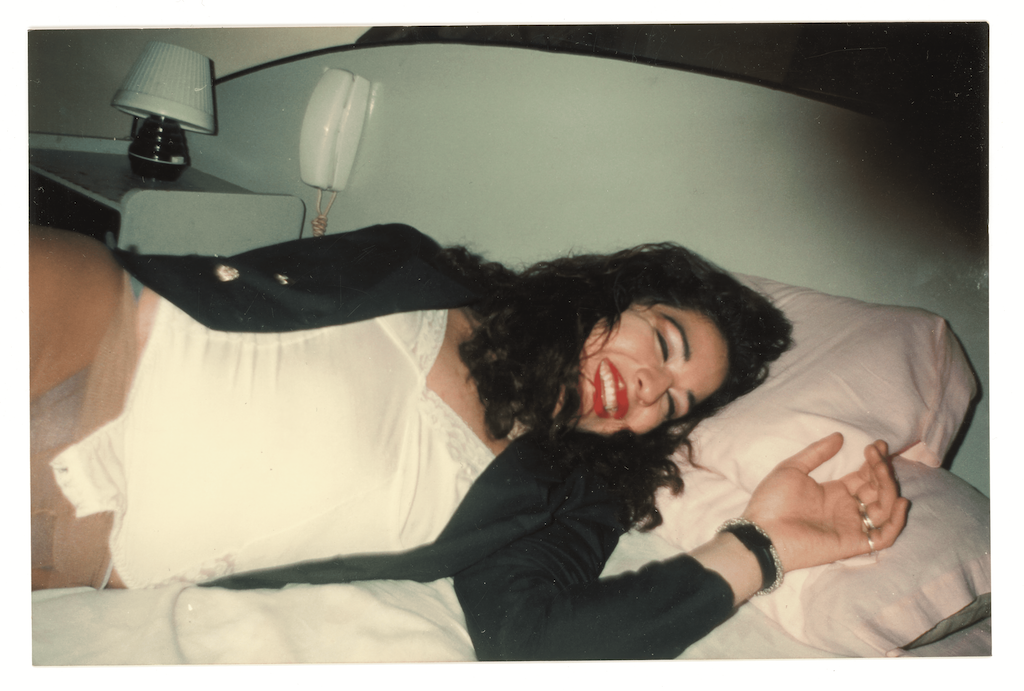

For many years, Belén was "Eva." She began portraying her at 20 and soon learned of a curse. All the trans women who played Evita died at 33. "As I approached that age, around 29 or 30, I got the idea that these were my last days. I lived dressed like an old-fashioned lady, people waited on me in bed, I lived in bedclothes. I had developed that Esther Goris syndrome, who lived with the character attached to her for I don't know how long. I had become consumed by the character. I thought I was going to die.".

She realized the curse wasn't real when she reached that age, but Eva remained a constant presence throughout her life. With the Gender Identity Law passed in Argentina, she legally changed her name to Belén Eva Carlocchia.

“We must stand united, because otherwise, they will kill us separately.”

That law was a watershed moment for her and so many other trans people. “It brought us into democracy in Argentina because it was the moment the State recognized us as citizens and made us equal to the rest of society. Trying to take away those rights through modifications, or eliminating the law altogether, would be a return to clandestinity,” she says, referring to the various attacks the legislation has suffered under the current government of Javier Milei.

The photobook about her life culminates with her years in exile. Of those tragic years, perhaps what she remembers most is the feeling of loneliness and helplessness. Something that, thankfully, is far behind her today. Although she is thousands of kilometers away from her friends and colleagues at the Archive, she shares thoughts, conversations, and life plans with them.

“We have to be united, because otherwise they’ll kill us separately. And we have to be alert. In the times we’ve been through, when they’d arrest you just for going out on the street, what we did to resist was live in community so that if something happened to us, someone would be there to help,” she says.

That, she asserts, is what will save us. That community life about which trans women and friends have taught her so much throughout her life. The book will be presented on Saturday, September 6th at 8 PM in Parque de la Estación (Juan Domingo Perón 3326, CABA), as part of the Migra Book Fair .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.