Mexico: seven transfemicides in one month

Activists point out that the increase in hate crimes goes hand in hand with violence on social media and in some political sectors.

Share

MEXICO CITY, Mexico. In August, at least seven trans women were victims of transfemicide in Mexico, according to reports from activist groups in the country. The victims were Eli, Katia, Joseline, Michelle, Montserrat, Guadalupe, and Mónica. These hate crimes were characterized by violence against their bodies and the use of firearms. In only one case has an arrest been made.

Activists frame the increase in hate crimes within a context of hateful and disinformation narratives spread by right-wing politicians and content creators. This violence escalated after a trans woman reported on social media that a police officer denied her access to the women-only subway car in Mexico City.

One act of violence among so many others

Regarding the impact of hate speech, Ximena with X, a non-binary trans woman and human rights defender in Sinaloa, explains that the urgent needs in non-centralized territories are different: survival.

“We get together for funerals, to heal wounds, to figure out how to get the one who was locked up for stealing to eat out. We don’t have time for anything else,” she says.

“Trans women from the periphery, from rural areas, are fighting to survive. If a politician misgenders us, if a religious figure spreads hate speech, it doesn't mean it doesn't affect me, but it's not an emergency. I don't deny its impact, but those of us who don't have a full voice have other urgent needs. In non-centralized cities, in towns, in the mountains, we're more worried about food, about having a place to sleep, about being allowed to work,” she adds.

They were activists, migrants, stylists

On August 4, the body of Eli Sánchez, originally from Veracruz, was found. She had stab wounds and was discovered in the beauty salon where she worked in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Activists held a protest in her memory. Authorities arrested a man and presented him before a judge as the alleged perpetrator of her murder.

Katia Medina was an activist. On August 9, her body was found with signs of violence in Ciudad Guzmán, Jalisco. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico demanded that the Mexican government conduct an investigation that takes into account her status as a human rights defender.

🏳️⚧️ #JusticeForKatia

— diverse collective (@diversoudg) August 11, 2025

On the State Day Against Hate Crimes, we demand that the murder of Katia Daniela Medina, a trans woman and human rights defender in Ciudad Guzmán, be investigated and prosecuted as a transfemicide.

No more impunity. ✊🏳️⚧️ pic.twitter.com/jTmJOKTS72

On August 10, Joseline Páez was found unconscious in the street with signs of physical violence. Her condition was critical. On August 16, she died in a hospital in Zapopan, Jalisco, as a result of the beating .

#JusticeForJoselinnePáez 🏳️⚧️✊🏽 On August 18, 2025, Joselinne Páez, a trans woman from Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco, died after being brutally beaten days earlier. Local activists are calling her murder a transfemicide and a hate crime, the second such incident in the state… pic.twitter.com/cYg5g33mKB

— Yaaj México® (@YaajMexico) August 19, 2025

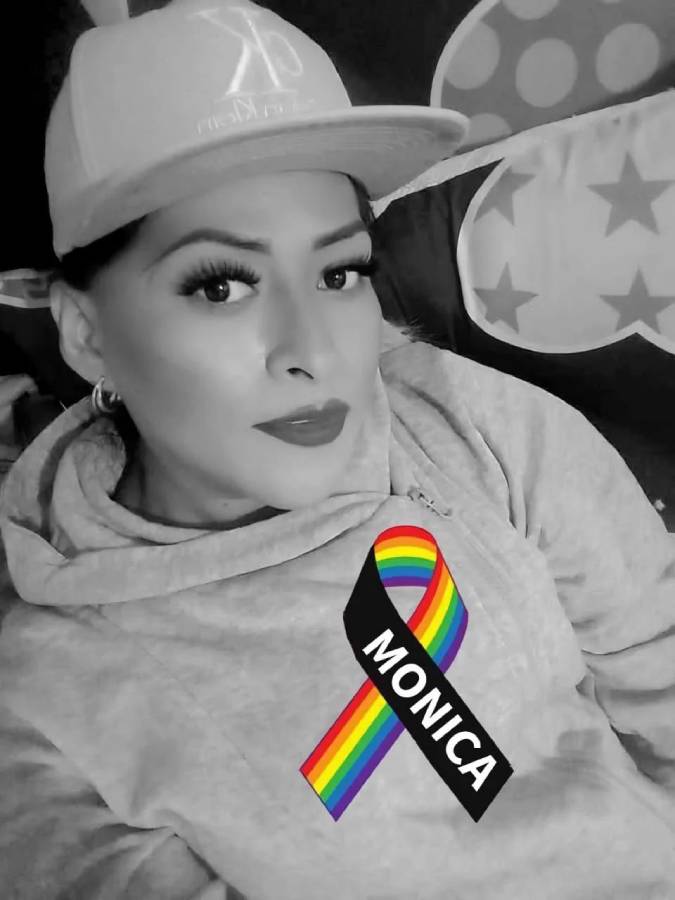

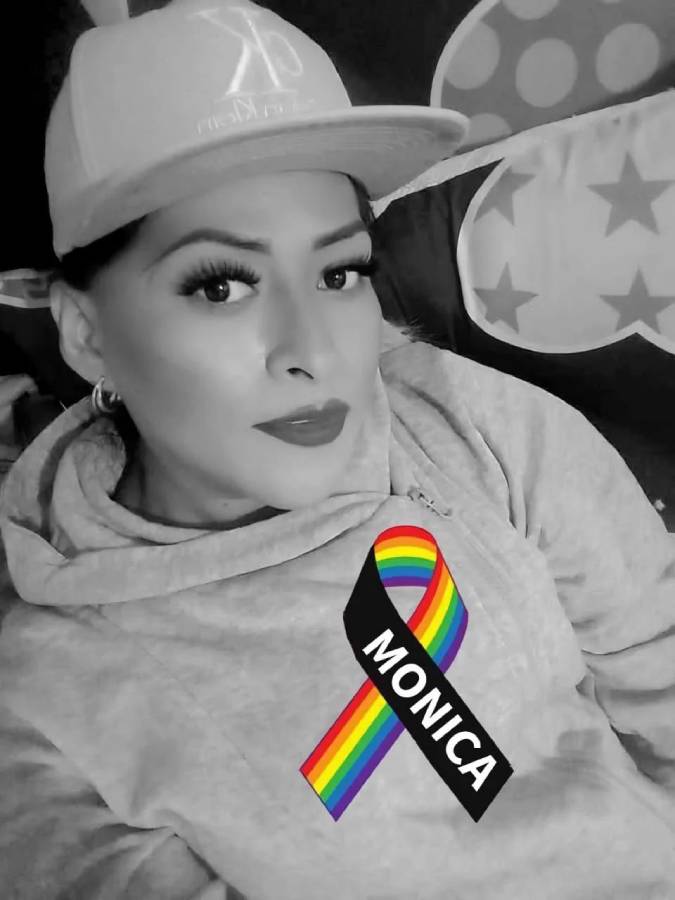

Mónica Hernández was originally from Mexico City. She was murdered in the street in Guanajuato on August 15th, and her body has not been released to her friends . The Prosecutor's Office claims they cannot release it because Mónica did not have a registered birth certificate. Her friends say she migrated at the age of 12 as a result of family exclusion.

Michelle Iturbide would have turned 38 on August 18th when she was riding her motorcycle to her birthday party. Men in a pickup truck intercepted her and shot her on the Puente Ixtla – Amacuzac highway in Morelos.

Montserrat Martínez was murdered on August 20 in Jonuta, Tabasco. While working at a bar, two men shot her at point-blank range and left a threatening message on a piece of cardboard.

Guadalupe Arias was beaten to death in her home in Xochimilco , Mexico City, on August 21. The assailant tried to flee but was apprehended by neighbors.

Transfeminicidal violence on the rise

So far in 2025, at least 27 trans women have been murdered in Mexico, according to documentation compiled by the Transcontingenta and the National Assembly of Trans and Non-Binary People .

For its part, the National Observatory of Hate Crimes records at least 51 LGBT+ people as victims of murders and disappearances in 2025.

Letra S 's monitoring shows that transphobic violence has been on the rise in the country over the last three years. The organization has been documenting violent deaths motivated by prejudice against LGBT+ people for more than two decades.

In Mexico, 5 out of 10 trans women are murdered with firearms. This violence occurs within a context of militarized security and territorial conflicts between organized crime groups, impacting cis and trans women differently. This is according to the report " Gender Violence with Firearms in Mexico (2021)," published by Intersecta and other organizations.

The importance of the social family

Ximena, whose name is X, points out that trans collectives face obstacles in influencing investigations. Prosecutors do not recognize them as key actors, which prevents cases from going unpunished.

For Ximena, it is vital to include “social families” —friends, collectives and community networks— in the justice processes, since many blood relatives of the victims reject the identity of their trans daughters.

“There are still families who feel ashamed. The last thing they want is for it to become public that they had a trans family member, for the specific violence to be discussed, and for the justice process to be separated from the restroom for safety reasons, because they think there could be reprisals for reporting it,” she explains.

Struggles organized with searching mothers

At Presentes, we have documented cases of transfemicides where the victims were previously disappeared. From Mexico City, Rocío Suárez, director of the Center for Support of Trans Identities, explained the importance of framing these violent deaths within other phenomena of violence.

“It is important to name these deaths from other places and other social phenomena and contexts that are intersecting with violence against trans women. The intersectionalities we notice are necessary: disappearance, contexts of mobility, the presence of organized crime and the increased use of firearms.”

In the north of the country, Ximena, whose full name is Ximena X, tells Presentes that the collaboration between trans collectives and the mothers searching for their missing loved ones has opened an unprecedented path in the defense of human rights under the slogan: “Without the families, nothing.” In Sinaloa, for example, trans collectives have learned from Sabuesos Guerreras —the largest search collective in the state—not only to denounce the extreme violence of transfemicides, but also to undertake searches for missing trans women alive, with the participation of their extended families.

This alliance has allowed the experiences of mothers, accustomed to tracing the disappearance of their children in contexts of impunity, to intersect with the urgent need of trans collectives to make visible and demand justice for their dead. They demonstrate that gender violence and forced disappearance share the same web of silences and institutional omissions.

Between impunity and the criminalization of transfeminicide

In Mexico, transfeminicide is only classified as a crime in five states: Nayarit, Mexico City, Baja California, Baja California Sur, and Campeche.

Activists denounce the lack of implementation of the National LGBTI+ Action Protocol , which aims to guarantee access to justice for these populations, and the high levels of impunity that leave victims without recourse. Although 13 states include the aggravating circumstance of hate based on sexual orientation and gender identity in homicide cases, it is not applied in investigations.

Currently, in various states, trans activists are working to have transfemicide classified as a crime at the local level. They are also seeking federal legislation, through Recommendation 42/2024 of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), to reform the national penal code and specifically define transfemicide as a crime. Furthermore, they are working to guarantee other rights such as identity, education, health, work, and housing.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.