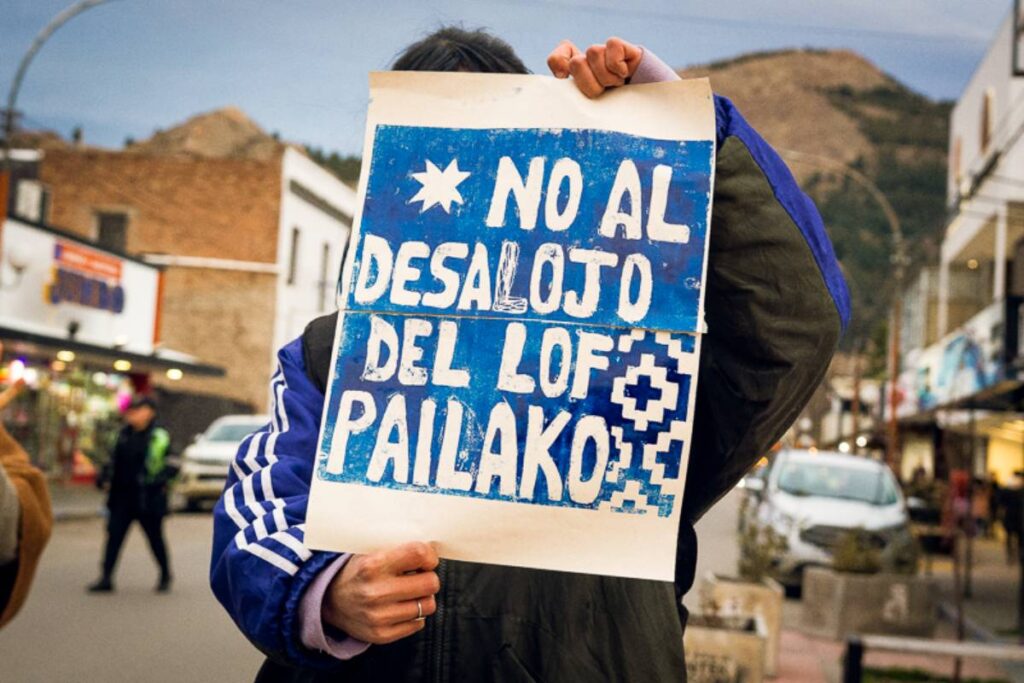

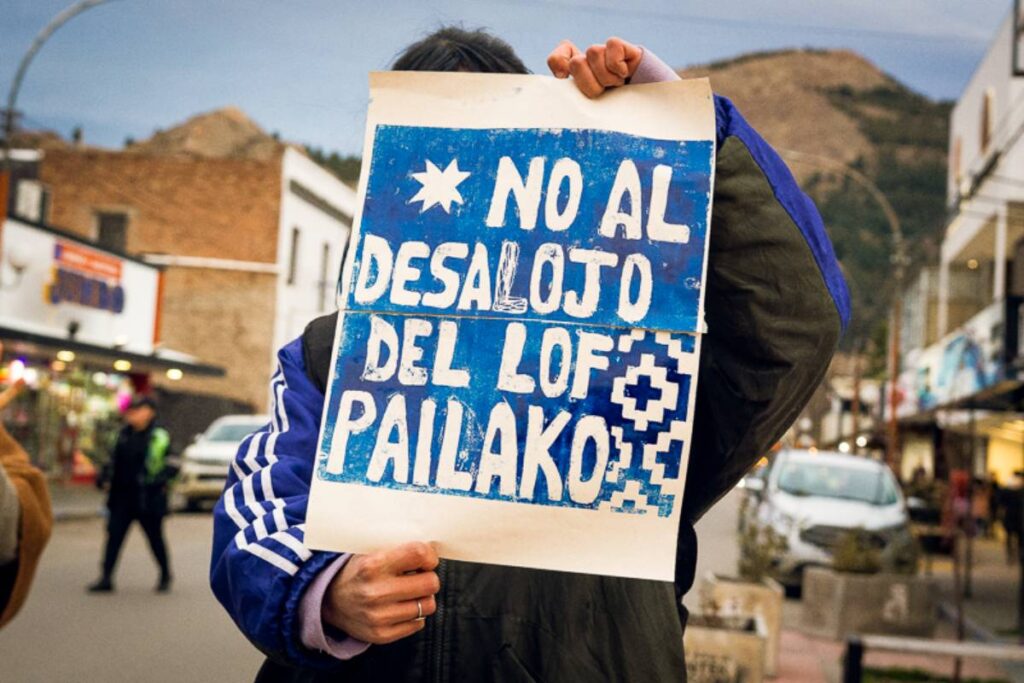

Persecution of the Mapuche people: Justice sentenced two members of Lof Pailako

In a trial marked by irregularities, the Federal Oral Court of Comodoro Rivadavia sentenced Cruz Ernesto Cárdenas to three years of suspended prison and María Belén Salina to one and a half years for aggravated damage and trespass.

Share

On Thursday, August 21, Cruz Ernesto Cárdenas and María Belén Salina, members of the Lof Paillako, a Mapuche community that claimed a territory in Los Alerces National Park in 2020, . The Federal Oral Court of Comodoro Rivadavia, presided over by Judge Enrique Baronetto, sentenced Cárdenas to three years of suspended prison for trespass, aggravated damage, and aggravated assault on an authority figure, while Salina was sentenced to one and a half years of suspended prison for aggravated damage only. The Salina family (often incorrectly referred to as Salinas) historically lived within what is now the National Park. In fact, the area is known as Paraje Felidor Salinas, named after Belén's great-great-grandfather. That's why she wasn't charged with trespass, while Cárdenas, her partner, was.

However, while only one person was charged and convicted of trespassing, the entire community was already evicted last January. Chubut Governor Ignacio Torres, then-President of National Parks Cristian Larsen, and Security Minister Patricia Bullrich all personally participated in the operation. Hundreds of federal troops were also present, but upon arriving at the disputed territory, they found no one.

The Lawyers' Association, the team that led the community's defense, expressed in a statement that, once again, there was a lack of impartiality in this trial. They characterized Judge Baronetto as "absolutely directed by the Federal Prosecutor's Office, which was effectively the one who conducted the trial throughout. This explains why they rejected all our evidence and accepted everything from the Prosecutor's Office."

A trial ends with the final words of the accused, and then the verdict is delivered. However, after that moment, the judge once again gave the floor to the prosecution and the plaintiffs. "An unprecedented ruling that some of us veteran lawyers with more than 40 years of experience have never seen," reads the statement from the defense team.

Long drag chase

Belén Salina said in a statement, "Why so much cruelty against Lemu (Cruz Cárdenas), against us? We've never had any problems with anyone; you can confirm that by talking to the people here. Even the same park rangers who are accusing us, we've never had any problems with them."

The cruelty he refers to has a long history. In January 2024, during the fires that ravaged Los Alerces National Park, Governor Torres publicly named him by name as the perpetrator of the fire, while also offering a reward for information that clarified the cause of the fire. And he never brought him to court, where, unlike the media, evidence is needed. Salina continues: “The problem is our Mapuche identity; the problem is denouncing the authoritarianism and subjugation that National Parks exerts in this area and the privileges of those with money.”

Eduardo Soares, the Union's lawyer, agrees: "While they were there without invoking their Mapuche status, everything was going on normally. When they reconnected with their historical memory, their ancestry, their worldview, and made it known, the conflict was immediate."

Gustavo Franquet, also a defense attorney, says: "We always say that the Mapuche are clearly subject to criminal law as an enemy." The problem begins from the outset, as the conflict is handled in the criminal court system. "In civil court, the judge has to say, 'Look, show me your arguments, and you also show me your arguments, and then I'll compare them.' But in criminal court, there's no comparison of rights. The community is only tried for an alleged crime." From there, the judicial imbalance continues to escalate.

During the trial, Cárdenas was held in pretrial detention for alleged "risk of flight" despite having voluntarily appeared before the court to participate in the trial. Before the hearing began, the defense team warned that of the 21 witnesses proposed by the defense, the court would only accept five. It was argued that redundancy should be avoided and that many of the Mapuche people would say essentially the same thing. The same criteria were not applied to the other side. The prosecution presented 19 witnesses, and all were accepted without the suspicion that, because they were all white, their statements would be redundant.

Discrimination at all levels

The discriminatory treatment and denial of Mapuche identity cut across all levels: judges, prosecutors, officials, and witnesses. Franquet speaks about the interrogation of former park superintendent Ariel Rodríguez Albertani, who filed the initial complaint in 2020: “We asked him, 'Did you participate in the dialogue table?' The response was, 'I wasn't going to participate in any dialogue table. I've known Cruz Cárdenas my whole life, and I say, he's not Mapuche.'” A park ranger testified as a witness that “Being Mapuche is an ideology.” The prosecution's statement said that the conflict began when the couple “began to perceive themselves as Mapuche.”

History of dispossession

This denial of Mapuche identity is related to the history of both the place and the people convicted today. Kaia Santisteban is an anthropologist with the Study Group on Altered and Subordinated Memories. She prepared a historical-anthropological report on the community and testified as a witness at the trial.

Santisteban told Presentes that in the first censuses, "the only registration categories that existed were those of Argentines and Chileans, and, for example, no mention was made of indigenous or Mapuche affiliation. So, in order to remain there, people understood that they didn't have to identify as Mapuche. And it's from these experiences of inequality that today, in the present day, the young people of the Paillako community decided to begin this process of reclaiming the Mapuche identity in the territory. The day before I was due to testify in court, a National Parks official publicly said, 'Oh, now they wear a headband and they're all Mapuche.'" This idea of taking advantage of the Mapuche, of the indigenous, to obtain territory is something that must be dismantled, because it's what they use to delegitimize these processes. Just as there's a contradiction because just as they use this discourse to say, 'Oh, now they're Mapuche,' they also say, 'But they don't dress like Mapuche and use urban clothing, cell phones, etc., so they're not.'"

Santisteban relates that the current settlements in the Lake Futalaufquen area date back to between 1890 and 1920, when many families displaced by the Argentine military conquest of Patagonia were looking for a place to settle and move forward with their lives. The boundaries between Chile and Argentina were still unclear, decades before the creation of the province of Chubut.

“Many of the former residents we spoke to allude to a life before and after the arrival of the National Parks Administration. Specifically, starting in 1937 (when the Parks Administration arrived), for example, certain ceremonies began to be prohibited, restrictions on free movement within the territory were imposed, grazing fees began to be imposed, and the Parks' policy of recognizing temporary land grazing permits meant that only one family member was recognized, meaning the rest of the family members were not recognized on those permits and had to leave the area.”

"A semi-feudal situation"

Gustavo Franquet says, “The situation at Los Alerces National Park seems to me to have traces of a semi-feudal situation. When the National Park arrived, it found a lot of people who had been settled there forever. What was communicated to these people was that they had no rights to the land they lived on. And that from then on, these lands belonged to National Parks, to the National State, and that they could be granted the possibility of living there. To this day, these people live there without being owners at all. The famous private property that is above everything else is beyond their reach. These people are on loan. The thing is, of course, being indigenous, being indigenous peoples, they weren't recognized any rights, nor were they expropriated, nothing.”

Belén Salina's statement also reflects this: "Sometimes I try to understand and think, why so much injustice? Why this circus? So many questions, and I can't find answers. I think it's the same thing they did to our ancestors; that's why they went into hiding, because of the exhaustion, the tiredness, and the pain all this generates. We can't freely be who we are."

No possible way

As is typical in trials involving Mapuche territorial disputes, the court avoids applying current Indigenous law by focusing on the right of way. It states that Indigenous peoples have constitutional rights but should demand them through the appropriate means.

Regarding this, defense attorney Franquet referred to the statement at the trial of Gabriel Nahuelquir, of the Nahuelpan Lof (Nahuelpan Lof) and a member of the provincial Indigenous Participation Council. "We asked him, 'If you follow the State's procedures to obtain land, will it be possible?' And he said, 'No, I don't know of any case.' Was that only Nahuelquir's opinion, or ours? No, the Inter-American Court, in a ruling against Argentina, said exactly the same thing. It said, 30 years after the 1994 Constitution was passed, Argentina still has no law that regulates and enforces the right of indigenous peoples to access land. It's the same old debate. They say, 'No, well, it's not the right that's being discussed, but rather the method, the path, the facts.' Well, what's the correct path? There isn't one."

We are Present

We are committed to a type of journalism that delves deeply into the realm of the world and offers in-depth research, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related Notes

We Are Present

This and other stories don't usually make the media's attention. Together, we can make them known.