Same-sex marriage in Argentina: 15 years of the law that strengthened democracy

After years of struggle, the LGBT movement achieved one of its most important milestones with the legalization of same-sex marriage. Argentina was the first country in Latin America to grant this right and the tenth in the world. Activists share their experiences of activism and their lives after marriage.

Share

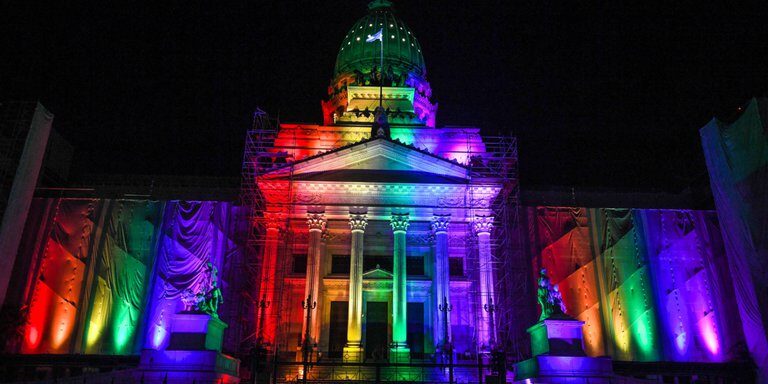

The night of July 15, 2010, was unforgettable, not only for the passage of the law in the early hours of the morning, but also for the cold. Argentina became the first country in Latin America to have marriage equality. The law's approval was the result of more than 30 years of activism for LGBT rights and the political will of the government led by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Vilma Ibarra and Silvia Augsburger drafted the initial bill, and Juliana Di Tullio presented the final version (originally submitted by Eduardo Di Pollina). It sparked a series of heated debates both inside and outside the chamber.

Marcelo Ferreyra has been an LGBT rights activist since the 1980s. Alongside figures like Carlos Jáuregui and César Cigliutti, he campaigned for civil rights. “At that time, we were in the midst of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, and we saw many cases where, because relationships weren't legally recognized, when one partner died, the other was left destitute. Or relatives who had never cared for the deceased would appear to claim property,” he recalls of those early days when he began to weave the debate for marriage equality.

At that time, Ferreyra recalls, the Argentine Homosexual Community (CHA) had other priorities, but "from these experiences stemming from the issue of couples facing the context of HIV, we began to consider that legal recognition of the couple was a necessary issue," he adds.

Rights for all

María Rachid, head of the Argentine Federation of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Trans (FALGBT), recalls that when the votes in favor were announced 33 to 27 in front of the National Congress, the plaza erupted. “With emotion, with joy, with the pent-up anguish of uncertainty,” she remembers.

“That approval wasn’t just about the concrete rights that same-sex marriage entailed—the right to leave a pension to your loved ones, the right to inheritance, to share health insurance. The main thing was the recognition of equality by the State. A key tool to continue working against the discrimination and violence that our community and LGBT people still experience in Argentina and around the world. Without that tool—the message of equality from the State—it’s very difficult to build real equality.”

José María Di Bello, an LGBT rights activist and the protagonist of the first same-sex marriage in Argentina, also emphasizes the notion of equality. “The struggle wasn't for the institution of marriage itself, it was because we were disadvantaged, unequal. The law introduces legal equality, and that legal equality drives social and cultural change. Which is the most difficult transformation. It's the one that, for example, is now faltering due to hate speech and the social shift towards a conservative right wing under the current government.”

“ The Equal Marriage Law subsequently promoted a large number of positions and new rights or recognition and restoration of rights. Two years later came the Gender Identity Law, and all of this was precisely related to that construction and that social and cultural transformation that equal marriage began to bring about.”

Building new struggles

The night of July 15th was marked by uncertainty after an arduous and exhausting process that ended in boundless joy, recalls Martín Canevaro, a member of 100% Diversity and Rights. “That approval meant that the LGBTINB+ movement was recognized as a relevant social actor in our country and deepened the process of greater political participation for our community. But the most important thing was the ability to build pluralistic and cross-cutting consensus to expand rights.”.

“At the level of society and its institutions, it allowed us to move beyond the medical discourse that historically pathologized us and into the realm of human rights, initiating a process of social recognition and appreciation of sexual and family diversity. Essentially, it reduced the social costs of visibility for those of us who do not conform to the mandate of heteronormativity and increased levels of freedom to express the diversity of sexual orientations and gender identities, especially for young people,” adds the LGBT activist.

Canevaro married Carlos Álvarez Nazareno on April 15, 2010, two months before the law was passed. “Judge Guillermo Sheibler’s ruling declared the articles of the old Civil Code unconstitutional, as they were interpreted as an impediment to marriage. This led to a prosecutor’s appeal regarding the scheduled date for the civil ceremony, which meant we had to suspend all the preparations. At that time, making ourselves visible to file an injunction involved a level of exposure that was difficult for most couples to sustain. We are proud to have been able to make that contribution,” she says.

For Mónica Santino, a lesbian and LGBT activist, the law “changed the nature or the way we look at our bonds and our relationships. I didn't show vacation photos, or my friend would show them to me. There were a number of issues that had to do with that kind of secrecy, and what marriage equality does is equalize.”.

And he adds, "to bring to light a number of relationships that perhaps had been hidden for some time, especially in older couples. All of that was wonderful, those years that followed between 2010 and 2015. In the first few days, the feeling was like having emerged from a clandestine zone."

The law also protected children

José María Di Bello also mentions equality and the importance of legal protection for children, which many lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans couples already had.

"They would say, 'No, because then they'll want to adopt,' but adoptions were already happening. There are hundreds of thousands of couples who had adopted; the problem is that legally, only one of the two adults had legal guardianship of the child. In other words, if the adult who had the adoption rights died, the child didn't necessarily remain in the other person's care; it sometimes depended on the court. And generally, that didn't happen; they would return to children's homes, and this is the lack of legal protection, the same with social services, etc. So, that child was also in a situation of inequality compared to children of heterosexual couples who had been able to marry and who were adopted by those couples."

Lesbian kisses

“When I was 22, my partner and I went to the Civil Registry. We told each other our favorite numbers. Marian said it was 13, and mine was 5. Well, we got married on May 13th,” Rocío recounts. Eight years ago, her partner was the third same-sex couple to get married at the Olavarría registry office. Rocío remembers that it was “overly romanticized” and that, at least for her, she didn't fully grasp what it meant to have accessed that right. That is, until two years later, when, at Constitución station, Marian 's partner was arrested for kissing her.

“We’re grateful to have been married at that time. Having that marriage certificate and proof of our relationship was a way to say, ‘Tell me where you’re taking my wife,’” Rocío recounts. She vaguely remembers the day the law was passed because she was a teenager. “I remember seeing Norma and Cachita, that possibility of getting married, and understanding that from then on, we could ‘fit in,’” she adds.

To live love in equality

When they decided to get married, Mónica Santino and her partner had been together for 13 years. They wanted to get married under the government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and did so in November 2015. “It was like a tribute, a political recognition of that desire for us to have that law. We also wanted a legal framework for our daughters.”.

For María Rachid, the law meant protecting her family, her partner, and having a child. “It wasn’t just the equal marriage laws; there were many other important laws for our families, like the assisted reproductive technology law, without which we wouldn’t have been able to have the beautiful son we have today. That equality, but also those rights, changed our lives. Another possible and beautiful life.”

Although he didn't have much faith in marriage, Marcelo Ferreyra got married in 2013. "When we bought the property where we live, we were figuring out how to handle the paperwork, and the lawyer told us the easiest thing to do was get married," he says, laughing. Today, he and his husband have a three-year-old daughter, and he adds that they don't experience any hostility from society. "For me, coming from a background of activism of 30 years, it's a very powerful and rewarding change," he reflects.

There are no national statistics on same-sex marriage, only data by jurisdiction. According to the General Directorate of Statistics and Censuses (GCBA), from 2010 to 2024 there were 300 marriages between women and 394 between men.

A law to defend

The current government has launched numerous attacks against the LGBT community. The most violent was the Davos speech in which the president linked LGBT people to pedophilia. This speech was met with a massive protest that was replicated throughout the country. According to activists, this reaction is a sign that Argentine society, despite the hate speech, has settled the debate with LGBT people. “The Davos speech was a turning point. Society isn't stupid, and I believe in that, in a critical unity,” says Rocío. Rachid adds, “At the time, there was a segment of society that celebrated the passage of the equal marriage law and that today defends that great achievement. It's no coincidence that the first major mobilization against Javier Milei's far-right government was in response to the Davos speech.”

Activities

-Organized by various LGBT groups, on Monday, July 14 at 12:30 there will be a "Booklet for love and equality" in front of the Civil Registry, Uruguay 753, CABA.

-On the 15th anniversary of the enactment of the Equal Marriage Law, a talk will be held at the Patria Institute with the participation of María Rachid, Franco Torchia and Agustín Rossi.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.