The aunts: older trans women in Argentina fight for rights and weave memory

For trans people in Latin America, being over 40 means being a survivor. For decades, older transvestite and trans women in Argentina have organized to demand a law of historical reparations that addresses the state violence they have suffered over the years, as well as building networks in which they construct memory and everyday resistance.

Share

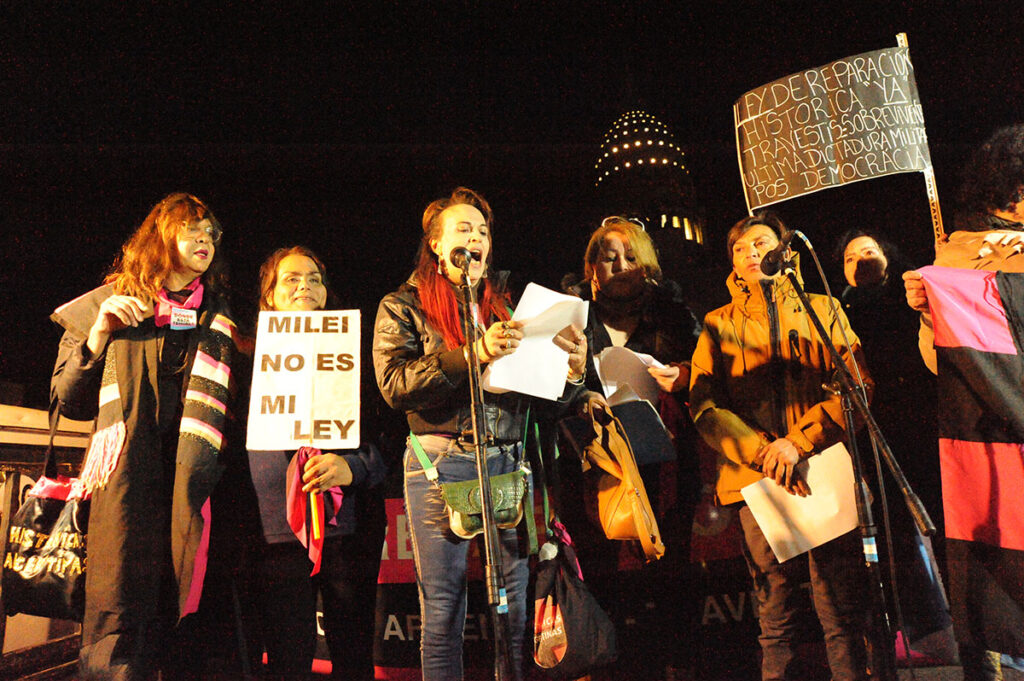

"You beat us, raped us, and murdered us, what more do you want?" Patricia Rivas shouts at about a hundred armored police officers behind helmets and shields.

It's May 24, 2024. The afternoon is freezing, and Plaza de Mayo, where the Government House is located, is surrounded by uniformed officers to prevent the Second Plurinational March for Trans and Travesti Reparation from proceeding along the street to the National Congress, where a stage awaits. The Ministry of Security under Javier Milei's government published a protocol that only allows demonstrations on the sidewalk , without blocking traffic, and also enables various mechanisms to criminalize the protest.

Patricia has flowing platinum blonde hair and walks in silver heels, wearing a black jacket that reveals a deep neckline. She is 58 years old, tall and robust, and appears strong, but her body and memory bear the scars of hatred and violence inflicted by the security forces. She is part of Históricas Argentinas, an organization of older trans women who identify as victims of state terrorism and multiple forms of institutional violence in a democratic society. They are survivors and demand to be heard.

The older trans women are accompanied by human rights and diversity activists. There are trans children and teenagers, non-binary people, lesbians, gay men, and many chosen families. Faced with the disproportionate police deployment with long guns and roaring motorcycles, the cry was unanimous:

– We are not afraid!

Institutional violence is a historical wound for trans and travesti communities. During the last civic-military dictatorship (1976-1983), people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, and trans and travesti people with particular ferocity, were persecuted and imprisoned for their identity. But for them, the prison cells remained a constant presence well into the democratic era, due to the criminalization enshrined in police edicts in several provinces that authorized the hunting of "transvestites" in the streets. These edicts remained in effect until 1998 in the City of Buenos Aires and for a decade afterward in the Province of Buenos Aires and other provinces. Trans and travesti people often say that for them, democracy only truly began in 2012, with the approval of the Gender Identity Law.

A decade ago, activism began for a law of historical reparation for trans and transvestite survivors, as well as the demand for a special pension.

For this purpose, different groups were formed: In addition to Las Históricas Argentinas, there is the Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina, an artistic and political project of historical recovery that went around the world and has been replicated in several countries.

In addition to historical reparations, these groups demand the fulfillment of their right to comprehensive healthcare for a dignified old age. But the bills remain stalled in Congress, languishing and losing their parliamentary status.

Marlene Wayar is an activist, writer, social psychologist, graduate of the University of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, and communicator. In a radio program, she explains :

What we want is for this society to sit down and discuss and acknowledge that we have an average life expectancy of 32 years, while that of cisgender people is 76 and rising, and that this constitutes genocide. Then we can look at the specifics of the law, but this is much more complex than a meager pension. As Wanda says, the State at some point has to recognize everything it has taken from us, everything it has taken from our lives.

Currently in Argentina, only the province of Santa Fe has a Reparations Law . This is an achievement and a precedent, but current political will is not opening new dialogues. On November 1st, organizations such as Futuro Trans and the Archivo, along with the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS), filed an injunction to compel the State to recognize their right to social security. “We also seek recognition and reparations for the institutional violence suffered by the trans and travesti population from the return of democracy to the present,” explains Marlene .

The marks of the dictatorship

“Historical reparation consists of two steps: one is for the Government to come out on the balcony and acknowledge all the mistreatment that trans people suffered, and the second is financial compensation that is not a minimum pension; we have to be compensated for the life they made us live,” says Patricia one Sunday afternoon, months after that March for Reparation where the police threatened and repressed.

We are on the terrace of her friend Eugenia, in the district of San Fernando, Buenos Aires province, near her home. Her voice is the narrator, amidst laughter and anguish, reconstructing that historical memory that she decided some time ago to reclaim in order to continue demanding justice.

– For a while, I was in a relationship, I worked as a hairdresser, and I buried that whole past behind me. When I went back to activism, I started having nightmares again about being chased, about running with my friends, escaping the police, and one of us getting run over and killed by cars. It's horrible to relive all of that.

Patricia also remembers the noises, the voices, and being detained and blindfolded at the Tigre police station in Buenos Aires province. “The one that now has a commemorative plaque saying that it was a detention center during the dictatorship,” she adds.

In 1981, when she was 14 years old, she was kidnapped there.

– It was five days, but for me it felt like an eternity. I was blindfolded, and all I could hear were the doors, the sounds of a heavy door opening and grabbing me. They'd take me to another place and torture me by holding my head underwater. Sometimes they'd point a gun and pull the trigger. Other times they'd rape me while saying, 'Do you like being a faggot?' There were always two of them, and when the first one finished raping me, I'd collapse to the floor, and then the other one would rape me.

In April 2023, for the first time in history, a trial for crimes against humanity featured a group of trans women victims of the dictatorship as key voices.

Carla Fabiana Gutiérrez, Paola Leonor Alagastino, Julieta Alejandra González, Analia Velázquez and Marcela recounted what they experienced in the Banfield Well , one of the clandestine centers of detention, torture and extermination that operated during the State terrorism.

Marcela Viegas testified wearing a thick chain necklace, bracelets, and a beret. The table in front of her was draped with the flag of the Argentine Transvestite and Trans Memory Archive. There, she recounted how, when she was about to turn 15, she was kidnapped on Camino de Cintura, in the province of Buenos Aires, and systematically tortured.

They put a hood over my head. I don't know where I was going. We had a blindfold and I could peek underneath. They threw me on a bed. They tied me up. And they applied 220 volts of electricity to me,” he said in his statement.

She added: “It’s a shitty thing to equate us with prostitution and vagrancy. I used to go to work every night because nobody was going to hire me as a transvestite.”.

In March 2024, judges sentenced the perpetrators to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity within the context of genocide. For the first time in Argentine history, military personnel were convicted of crimes including unlawful deprivation of liberty, torture, sexual abuse, and enslavement of transgender people.

Not all the survivors had access to the documents recording those arrests. Sometimes they weren't even recorded, or they were listed under different names. It was also very difficult for them to approach a police station to ask about a friend, first because they could be arrested themselves, and second because, who would they even ask about? Transvestite resourcefulness and humor—a muscle that helps them survive—meant that in "the zone" they all used their chosen names, their stage names, and nicknames that were a mixture of affection and playful teasing.

But none of that stopped them; if one was imprisoned, the others would find a way to get her "the baggage," as they called the shipment of essential items for the days that were missing.

Patricia knew that when she was arrested, she shouldn't sign whatever they gave her, but rather find ways to negotiate. When it came time to sign, she had to write: "I appeal, Your Honor." "You disgust me, you're wasting my time, I don't want to see you here again, or you'll never see the sun again," the judge told her back then.

Trans memory

Four months have passed since the Second March for Reparation, and on Avenida de Mayo, the door of a French-style building leads to the Trans Memory Archive. In this space, in addition to archiving and editing, there is a screen-printing studio, a bookstore with LGBT+ titles, and a lounge where the women hold meetings, have therapy sessions, and now, over pastries, coffee, and mate, give interviews. Sometimes here or in other spaces, they invite other adult survivors to share memories, talk, and discuss each other's needs.

In the Archive, some 20 older women search for and collect photos, letters, and newspaper articles that piece together the trans and travesti memory of a country that has tried and continues to try to make them invisible. With all of this, they create exhibits, souvenirs, books, and chronicles that they then sell to make a living and keep that collective trans and travesti memory alive. They dispel condescending glances and bring to light trans lives with all their nuances, colors, injustices, loves, celebrations, and connections.

Their lives and biographies cover many spaces, recounting what they have experienced.

At 59 years old, Wanda Sánchez shares the structural violence experienced by many transvestite and trans people of her generation.

– I saw so many of my classmates die, remembering how many of us there were. I outlived them all, everything that happened to us. I had to leave home at 13 to start being myself; I couldn't be there.

During this period of wandering, she began to be detained by the police, embarking on a journey through juvenile courts, institutions, and even a psychiatric clinic. “There, a saintly woman, a doctor, told me that it wasn't wrong to be homosexual, that the one who needed to change was my mother.” A bridge was built between her and her mother, though it was short-lived because her mother passed away a few months later.

He turned 18 in the clinic and when he left Argentina was already a democracy, but his ordeal was not over.

– They arrested me for existing. They came to my house to take me into custody. Sometimes I ended up at the police station with my shopping bags because I had just finished shopping and they arrested me.

It is her voice, but it is the story of many, of so many.

On a table, cloth bags and t-shirts with images taken from photographs, phrases shouted by a comrade at a march or during a chase, now transformed into a rallying cry, sit alongside books from friendly publishers and those produced by the archive itself. The first book published by the Trans Memory Archive is sold out, but others are still available and can be purchased on their website: 'Our Codes '; "If Your Mother Saw You," about the life of trans activist and one of the founders of the space, Claudia Pía Baudracco; and the most recent: 'Kumas,' a word meaning "friends, comrades, sisters" derived from Carrilche , the transvestite language that emerged in the 1940s to allow them to communicate with each other and survive the police and attacks.

Mónica, 71, says that having her own home helps her a lot. She built it with the money she earned from prostitution. “I didn’t waste anything,” she says. Unlike most, she has a supportive family, but this shared space is what “pulls her out of the pit of depression, because being with everyone helps her not to think so much.”.

She was also called “the gringa.” Her story in the book “Kumas” is interwoven with family stories, tales of friendship, but also of arrest and torture. But beyond the accounts of violence, there are also the nights of glitz and fun: the carnivals, the shows in bars.

Getting to know these women allows us to piece together the complete history of Argentina.

Teté is 60 years old, wearing her immaculate white apron as she works as an archivist. She has short, gray hair and a firm voice that betrays her sadness. She doesn't break down; she exudes the confidence of someone who knows who she is and who she was.

– It was an ugly situation, because when I was 13 or 14 years old I liked to go out because I was always very independent, and to be arrested, to be put in a patrol car and driven around so the whole town could see that you were a faggot.

She was born in a town in the north of Santa Fe province, and in her words the lines between dictatorship and democracy blur. At that time, she hung out with older friends, but they too were being pursued by the law.

– A judge summoned that gay boy to court and told him that if he continued hanging out with me, he would be arrested for corrupting a minor. That's how I lost friends.

All that context of discrimination meant that she couldn't finish her studies either: “It was very difficult to finish primary school. The last year was seventh grade and it was a matter of survival.”.

It wasn't until 2013 that she was able to resume her secondary studies, completing them in 2016. And she continued. She managed to complete two years of a degree in Social Psychology at the Social Psychology School of the State Workers' Association (ATE). "I struggled a lot to find a job," she explains.

In 2000, he became involved with the political organization Movimiento Evita, and since 2008 he has worked at the Magdalena V. de Martínez Provincial Public Hospital in Pacheco. He started doing cleaning and now works in the administrative area.

She has been in a relationship since 1992 and has worked in the Archives since 2018.

This is my space, my place, the one I would always choose. Even though I have my family and my partner here, this is something else entirely. Here, we're among equals. We might have differences, we have fun, we enjoy ourselves, it lifts our spirits. It fills my soul; it's truly a place I would always choose to be.

She says it out loud, but she also tells it with every knowing glance and every laugh. They're at the table, brought together by sharing anecdotes, joys, carnivals, and an infinite transvestite DNA. A chain of words, tools, references, concepts, and pride that transcends decades and geographies.

“I never thought that at my age I would one day be able to tell my story,” says Carola.

On September 29, Carolina “Carola” Figueredo turned 62, almost double the average lifespan of a trans person. She is now sitting with her colleague from the Trans Memory Archive, Marcela Navarro, in the library of the Alliance Française in Buenos Aires. The space is immense, filled with books; it is the largest Francophone library in Latin America. But what isn't there is what they will present at this meeting: the Archive's books, containing their stories , told by themselves, about their lives and the lives of those who are no longer with them.

“All I ever heard were reproaches. Everyone judged us, condemned us, but we were never given the opportunity to express who we really were. We were never understood,” Carola explains, and in her words the curve shifts to pride as she explains how the Archive was established as that redemptive project where they could speak out and become visible.

“This space was a second chance. Here we all met again, but at a different time and in a different situation. Now we were free because, starting in 2012, we obtained the Gender Identity Law. I never thought I would have the freedom to tell my story, to have everyone listen, to have them pay attention, and that makes you feel important,” she says to an audience that listens, asks questions, sheds tears, and smiles. Her body seems fragile, sometimes she seems shy, and then, suddenly, her biography comes to life, and she begins to weave stories in the air that should be in every national education textbook. Her story is also the story of a collective.

Beside her, Marcela exudes the presence of a school principal. Her black hair, pulled back in a ponytail, seems to crown her like a showgirl's cap. She will talk about all the processes carried out in the Archive, ask Carola for more testimonies, and treat her in a maternal way.

'This one left, this one was killed, this one died' was the title of the Archive's first exhibition, held in 2017 at the Haroldo Conti Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, located on the grounds of the former ESMA (Navy Mechanics School). In this former clandestine detention center, they managed to transform their memories into a manifesto. This time, they weren't forced in; they were the force and the resistance. She speaks with a measured and present voice, explaining, "I receive the material and separate it: daily life, sex work, carnivals," and recounts how she pieces together the conversations and reconstructs the stories. Besides photos, there are letters, documents, cards, flyers, and "many plane tickets and travel records." It's not that they were living the high life; these flights represent exile, escaping to survive.

“I fill out the forms and write down the year and name of the women in the photos. If someone has passed away, we try to find another woman who can help us piece together her story; after that, I write her biography myself. When a woman is still alive, I try to locate her so she can tell us her own story,” Marcela continues. On the other side of the group, there’s a table with some of the books and objects they produce.

We need work

“We have life to spare, but we need a job. We need something to live on, to keep going,” explain the members of the Archive. Sonia Torrese shares her story and explains that she was “flitting from place to place, wherever I could, like a swallow.” She too is one of those daughters expelled from her family home for being trans. Today, at 64, she has returned to that house, but to care for her parents. “My sister and brother didn’t accept me. They were very ashamed of me.”.

Sonia's blonde curls frame the words that timidly emerge to describe her. When she says that she used to be "very reserved, very stubborn," her colleagues stop her and remind her that she has the best memory. If someone sees a face in a photo and can't remember who it is, Sonia is sure to have the answer.

As a nurse, she explains that a neighbor asked her to go to the nursing home where his mother lived to treat her wounds. The first few times there was no problem, but then the nurses told the owner that she was transgender: “They immediately shut me out, they kicked me out.” This happened approximately seven years ago, in a country with a Gender Identity Law and no police edicts.

Currently, some receive a retirement pension, but very few. And since that's not enough, they have other jobs and seek help wherever they can. Wanda says she has a pension, plus she works at the Archives, on Saturdays she works at the Claudia Pía Baudracco Library , and she picks up supplies wherever she can. Most of them describe similar situations. At that moment, they all start talking at once, but they all say the same thing: they mention a colleague and express their desperation at not having any income.

“Sandra is almost 70 years old and is still working as a prostitute. It’s a shame that at her age she has to stand on a street corner,” they say about another colleague who also has no recognition from the State.

According to data from the National Institute of Statistics (INDEC), 80% of transgender and transvestite people are involved in prostitution. And only 32% have completed secondary education, according to research by the organizations ATTTA and Fundación Huesped.

To address this gap, Argentina passed the Transgender Employment Quota Law This law mandates the hiring of transgender people in the national government through a minimum quota of 1%, in addition to affirmative action measures aimed at achieving effective labor inclusion in both the public and private sectors. However, the arrival of the new government stalled the progress of this law, even adding transgender people to the unemployment figures.

The Transgender Employment Quota Law is named after the two historic activists who championed it and is only a first step. It is not currently being enforced, and the law itself is in danger.

“Unfortunately, the trans job quota doesn’t apply to our fifty-year-old colleagues,” Teté explains. “At this age, they don’t want you for anything, and even less so us,” she says, highlighting the connection between being an older adult and being trans.

Patricia shines brightly in the Buenos Aires afternoon sky. She's drinking mate and sharing a sponge cake with friends.

“I receive a disability pension, which is currently my only income because I have problems with the silicone I had injected years ago. It weakened my bones; my hip, for example, ate away the cartilage that connects the femur to the hip bone, and the silicone got into my spine. I feel a constant burning sensation in my back and around my kidneys,” she says.

The use of industrial silicone is a fairly common practice among trans people who cannot access implants. This is not a matter of vanity but rather a construction of identity; it's about looking more like who they truly are. However, being excluded from employment and healthcare often leads them to resort to these unsafe options with serious long-term consequences.

In Argentina, the report “Socio-Sanitary Conditions of Trans People,” published in 2019 by the Ministry of Health and Social Development, found that 83% of trans women had modified their bodies to align with their self-perceived gender identity. Half of them had injected materials into their bodies: 66% with liquid silicone and 17% with aviation fuel.

“Just this year, a friend of mine, like Silvina Luna, died because silicone damages your kidneys,” Patricia continues, citing the case of the model and TV host who brought the debate about methacrylate and liquid silicone to the forefront of the media. The difference is that transvestite and trans women aren't discussed or remembered in this way; they only do it among themselves.

Mothers, Grandmothers and Aunts

At the marches, there's often a sign that reads: "Mothers of the Plaza, the trans women embrace them." That phrase is also a rallying cry when the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo march—those women who, even today, in their eighties and nineties, continue to advocate for human rights, demanding answers about their disappeared children and grandchildren appropriated by the last military dictatorship. Transvestite and trans people know what it means to march to demand these rights be respected and for the right to identity.

“Memory, truth, and justice” is the phrase that demands justice for the human rights violations committed during the Argentine dictatorship. Trans women build memory by meeting together, searching for photos and stories of their comrades, and sharing them. But they also build truth by putting their own voices into these stories. So, what about justice? The time it takes for the justice system, the state, and society to respond and take action is insufficient to protect the older trans people who have survived. They use radio programs, television, podcasts, books, magazines, and meetings. They do this to connect with each other, to keep their voices alive, and also to ensure that all of society supports their demands.

Michelle came to Buenos Aires from Rosario, in the province of Santa Fe, because she was alone in her home there; here she found a family. “I thought I was going to die at 52,” she says, and everyone asks her why. “Because my mother died at that age.” And as she speaks, her long nails seem to guide her words. It’s hard to imagine her sad, because now she smiles and is part of this group of trans and travesti women.

“In the lottery, 52 is the mother,” one of the girls says, and it all has an air of revelation and casual conversation. The 52-year-old was Michelle's birth mother, because in the LGBT+ community, when they say there's a chosen family, the titles earned are real. Marcela has a very maternal air about her. “I told her, ‘Come over to my house and bring any photos you have.’ Then she came to the archives, started working, and earned her place,” she explains proudly. Now they live together but separately. How is that possible? “Well, she lives at the house of a gay friend across the street from me, but also at mine,” and there's the whole thing about tidying up, making the bed, and all those everyday things that create family life.

“The aunts,” as many call them, are much loved. Whether at an event or a gathering, if one of them starts telling a story, the young people calm down and are captivated by their voices. “Personally, what draws me in is the affection and respect they offer. It’s what we had the least of before. There’s respect and love; I’m very sensitive. You show me affection, and I’ll give you affection; you show me aggression, and that’s what I’ve experienced my whole life,” says Carola, her eyes always filled with emotion and gratitude. But the love that surrounds them must be accompanied by a present and supportive government.

Much more than a name

That second march for reparations, the one in May, after traversing the entire length of Avenida de Mayo, ended with a music festival and speeches in front of the National Congress. To the low-cut look of silver heels broken by police shoves, Patricia now added swimming goggles in case they decided to use tear gas during the repression. The LGBTQ+ youth present also learned a lesson in struggle and resistance, from what they shouted: "Trans Fury!" In organizations, archives, chosen families, and other adult spaces, there are always young people from the LGBTQ+ community working on urgent issues, ranging from logistics and registration to accompanying some of the "aunties." Sometimes it's listening to them, other times helping them with paperwork, but the interwoven generational fabric creates a loving network that once again defies all terror. Before the march ends, Patricia leaves them with a postcard of struggle; she looks at photographer Valen Iricibar and shows him her enormous breasts, laden with history. He does it with the police cordon behind him.

A couple of months later, when the interview seems to have ended and on that terrace in San Fernando, while everything is being arranged to close the day, Patricia, Pato, Aunt Pato, rebukes:

– Aren't you asking me my full name?

At that moment, all the ways of calling her gave way to what she is today, 12 years after the Gender Identity Law was passed: “Patricia Alexandra Rivas.” Her chest swells with pride, her eyes shine brighter, and the heart pendant around her neck seems to beat. It's not just a name; it's a fundamental part of the story of a collective.

For trans people in Latin America, being over 40 means being a survivor. For decades, older transvestite and trans women in Argentina have organized to demand a law of historical reparations that addresses the state violence they have suffered over the years, as well as building networks in which they construct memory and everyday resistance.

* German Federal Foreign Office

Learn about the project and more stories at https://cambialahistoria.com

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.