Eviction of Lof Pailako: a failed show and the plundering of indigenous territories

The spectacular deployment by the National Ministry of Security did not have the desired effect: by the time the Federal Police and the Gendarmerie arrived to evict Lof Pailako (Chubut), the community had already left peacefully. A political-judicial web of dispossession and human rights violations.

Share

*Collaborative coverage by Infoterritorial, Agencia Tierra Viva , Revista Cítrica and Agencia Presentes.

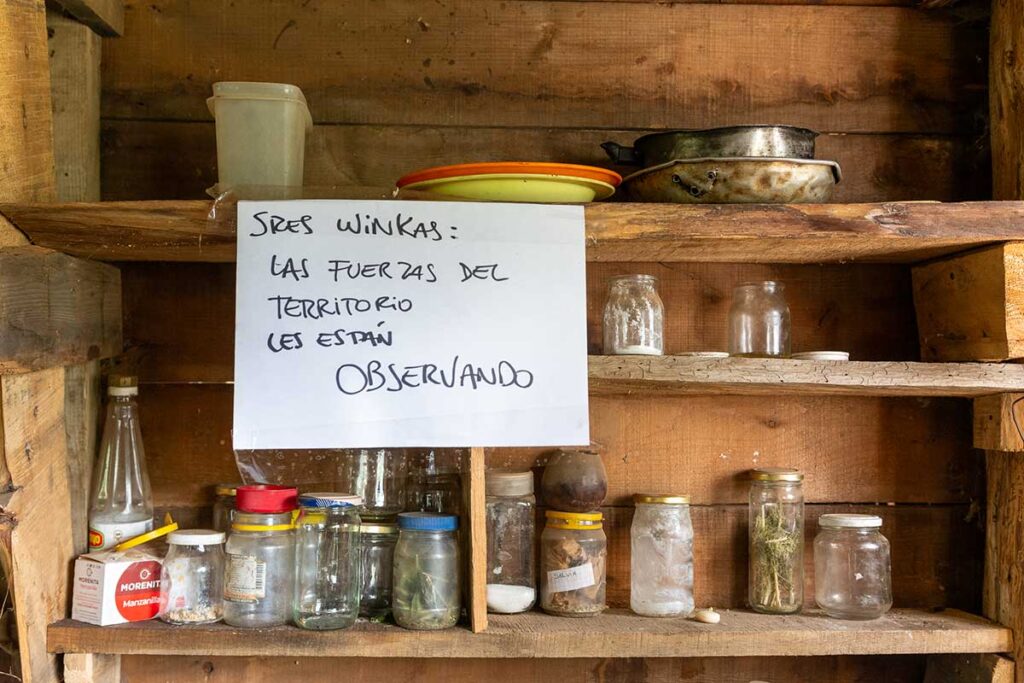

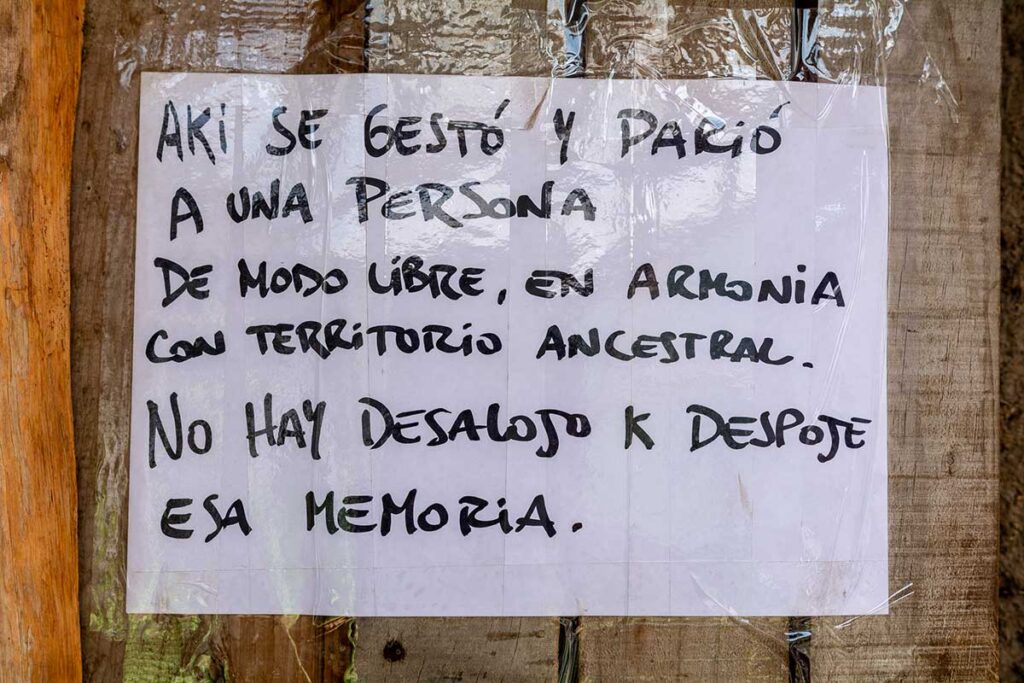

The eviction of the Pailako Mapuche community from their ancestral territory in Los Alerces National Park (Esquel, Chubut) had been announced with great fanfare. At 8:00 a.m. this Thursday, more than 30 vehicles from the Federal Police and the Gendarmerie, along with trucks, buses, and National Parks personnel, began arriving via Route 71. The scale of the operation to exclude a few families from their land is consistent with the racist rhetoric of the provincial and national governments and is based on a ruling by the Federal Court of Esquel. However, the Lof (Mapuche community) decided to withdraw peacefully beforehand, so the officers found no one at the site. Only a few signs were posted on what had been the community's houses: " The forces of the territory are watching you ." " Here, a person was conceived and born freely, in harmony with the ancestral territory. No eviction can erase that memory ."

“We knew this was going to happen, so we organized ourselves to ensure they wouldn’t encounter anyone. This whole circus is for nothing; they found empty houses. It’s a painful situation, but at least the members of the Lof aren’t exposed to being shot or killed by the government,” said Moira Millán, a weychafe (Mapuche leader) who supports Pailako’s claim to their territory.

The Lof community is asserting its presence in an area of Los Alerces National Park (35 kilometers from Esquel). This spiritual and identity-based process began in 2020. Currently, about twenty people live there: families with children. An educational center operates on the site. Had it gone ahead as announced by the government in recent days, it would have been the first eviction since the repeal of the extension of Law 26.160, the Indigenous .

The attempt to evict Mapuche families from their lands served as a cautionary tale, given the ongoing persecution of Indigenous peoples under Javier Milei's government. Other situations, such as that experienced last October by the Wichí community of Guerrero in Jujuy, reflect this pattern.

At the institutional level, the National Institute of Indigenous Affairs was first gutted. Then the National Registry of Indigenous Communities, whose function was to register pre-existing peoples in a national survey, was dissolved. The final blow was the repeal (by decree) of the decree that extended the Indigenous Territorial Emergency Law, on December 10.

Just 20 days later, the federal judge in Esquel, Guido Otranto, lashed out against the Lof Pailako. “Lashed out,” because the threats of eviction and institutional violence began when the families decided to inhabit the territory where their grandparents grew up.

A show that was announced and then thwarted

The eviction was a spectacle orchestrated by the national and provincial governments, the judiciary, and numerous media outlets. Security Minister Patricia Bullrich, Chubut Governor Ignacio Torres, and National Parks Director Cristian Larsen had all promised to be present. The minister arrived by helicopter around midday. Bullrich had also served as Security Minister during the military operations in which Santiago Maldonado and Rafael Nahuel were last seen alive. Her provincial counterpart, Minister Héctor Iturrioz, was also present. The press conference promised by the government never materialized.

The order from Federal Judge Otranto (known for his involvement in the forced disappearance case of Santiago Maldonado) is based on Law 22.351. This law was enacted during the last military dictatorship: it criminalizes “intruders” who use the facilities of National Parks and authorizes their eviction.

Without a final judgment

The actions carried out this Thursday were done without a final court ruling and without the presentations made by the Lawyers' Association, representing the Pailako community, before the Judiciary having been exhausted.

Faced with these abuses, the community resists. “We are always looked down upon. Our intention is to preserve this forest, to be able to raise our children and the children who live here,” stated Belén Salina, a member of the Lof, days before the eviction . Despite having avoided a situation of violence against the families, the community was forced to leave their homes, their land, and their animals in the Park.

On January 8, the Lof, the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights (APDH), the League for Human Rights and the Committee for the Freedom of Mapuche Political Prisoners in Puelmapu held a press conference in Esquel.

Speaking on behalf of the Committee, Millán criticized the government: “Today we see these architects of death coming to our territories and normalizing the narrative of criminal policies. They are vindicating the military regime. And during the military regime, a pristine ecosystem was destroyed to build one of the largest dams in Patagonia, which now supplies a private company. That is the logic they are now vindicating, not only the disappeared but also the plunder .” In this regard, he asserted: “They want to privatize areas of the National Parks, and we, the Indigenous peoples, are the thorn in their side.”

The dam Millán referred to is Futaleufú, built within Los Alerces National Park and commissioned in 1978 to supply energy to the aluminum company Aluar. Indigenous communities are also concerned about intentional fires. According to a statement released on social media by the Lof Pailako community, thousands of hectares are being burned to facilitate various extractive activities. In addition to the eviction, one hundred forest firefighters who worked in the park were recently dismissed.

At the conference, Millán pointed to the responsibility of previous governments for failing to regularize the land tenure of Indigenous peoples. Finally, he called for a boycott of the country's national parks, urging people to withhold entrance fees nationwide.

Solidarity with Pailako in Nahuelpan

While Patricia Bullrich was carrying out an excessive and costly deployment of security forces, 40 km away, in the Lof Nahuelpan, a group of self-organized Pu Lamien, from a support network for Lof Pailako, carried out an action to make visible, talk to and inform those arriving on the La Trochita tourist train about what happened in Los Alerces and the stigmatization towards indigenous communities.

For a while, the tracks were blocked, a flag was raised, leaflets were distributed, and people spoke with those about to board the train. There were tense moments when the police arrived, but no one gave in to the provocations, and the buses requested by the municipality took care of transporting the tourists.

“We came peacefully to break with the social narrative created about us by the mainstream media and racist society itself, where they portray us as violent, when all we want to do is inform. Unfortunately, ignorance and misinformation are a virus, a disease that plagues us as a society today. We came peacefully, and the police arrived to intimidate us, to use violence against people, and to push them,” Zamira Tacuman told us.

With all the repressive forces at their disposal, this small act of resistance and solidarity was able to take place peacefully and at a site emblematic of the protests. It was a way of embracing the struggle of the Lof Pailako and all the Indigenous communities criminalized by the provincial and national governments. In November, at the UN General Assembly, Argentina was the only country that voted against a resolution that violated the rights of Indigenous peoples.

The unequal legal battle: how the eviction came about

In 2020, the community reclaimed its ancestral territory, reaffirming its cultural and spiritual roots in the Mapu (land). There they cultivate crops, raise animals, and care for their children. Since then, they have faced threats and harassment. Those who live there are descendants of Mapuche settlers in what is now Los Alerces National Park, created by the Argentine State as part of its policies to expel Indigenous communities from Patagonia.

“For us, ‘pailako’ means ‘quiet stream,’” explained Lemu Cruz Cárdenas in a statement given to the Presentes Agency . “The stream that gives the community its name is formed by several smaller streams that flow down from the hill and combine to form a larger one. We used to live on the banks of that stream,” Cárdenas recalled. Today, he and María Belén Salina (members of the community) are charged with alleged involvement in forest fires that occurred in the park. There is not a single piece of evidence against them.

In response to the land reclamation efforts initiated in 2020, the National Parks Administration filed a motion with Judge Otranto requesting the eviction of the community. Initially, the judge authorized entry to the Lof (Mapuche community) to identify its residents. This was a preliminary step to the eviction.

Otranto then issued the eviction order, but it was suspended by the Federal Court of Comodoro Rivadavia. Following an appeal by the National Parks Administration, the Federal Court of Appeals of Comodoro Rivadavia ruled in favor of the national agency, and the threat of eviction was reinstated.

It is striking that, in the ruling of the Federal Court of Appeals, Judge Javier Leal de Ibarra argues: “It is duly established that Cruz Cárdenas and María Belén Salinas (Editor's note: note the misspelling of the surname Salina, a traditional family in the area) joined a Mapuche community that occupied the area known as the former Felidor Salina Settlement starting in January 2020. […] and that although they are descended from settlers who had permits to occupy land within Los Alerces National Park, no temporary permit has been granted to them for the specific area they are claiming.” Felidor Salina was the great-great-grandfather of Belén Salina, a member of the Lof Pailako. Like so many settlers in the area, he was granted a “temporary permit” for grazing and occupation in 1940.

On December 30, days after the repeal of the extension of Law 26.160, Otranto again authorized the eviction without a final ruling in the case and before the community had exhausted all legal appeals. The APDH (Permanent Assembly for Human Rights) also filed a preventive habeas corpus petition, which was dismissed by the judge.

On January 2, a court officer, accompanied by federal forces, notified the community of the eviction. They were given five business days (until January 9) to vacate the territory. The notification warned that the use of force and searches of homes would be authorized if "necessary." The information was presented alongside Danilo Hernández Otaño (superintendent of Los Alerces National Park) and Laura Fenoglio, a member of the National Parks Administration.

The argument put forward by National Parks for the eviction is to preserve the protected area. However, the UN highlighted in 2023 that “thanks to their knowledge and their relationship with the environment, indigenous peoples can help find solutions to remedy the damage caused by the triple planetary crisis.”

Los Alerces Park

Los Alerces National Reserve was founded in 1937. In 1945 it was declared a National Park, covering more than 280,000 hectares. These “protected” areas were created through the dispossession and violent eviction of the communities that lived there.

“The civil trial in which the ancestral rights of the members of the lof could be resolved, is languishing in a drawer of the Argentine justice system, thus preventing the possibility of bringing to light the traditional occupation of this territorial space by some of its members who are the fifth generation of the families who lived there, long before the creation of National Parks,” states a document signed by dozens of Mapuche communities and socio-environmental assemblies.

In the same text, they denounce that the area “is coveted by real estate, mining, forestry and hydroelectric interests”.

A state that defends its racism

Last December, the governor of Chubut declared: “This (provincial) government will go to the furthest extent of the law against those who seize property that does not belong to them, and they will be imprisoned. We must distinguish between our indigenous communities […] and these criminals who raise false flags to commit crimes, to seize private lands, or, for example, to occupy Los Alerces National Park.”

Similarly, on January 8, the Ministry of National Security, together with the Deputy Chief of Staff's Office and the National Parks Administration, issued a statement affirming that "after exhausting all legal avenues and attempts at peaceful withdrawal, the eviction of the self-proclaimed Mapuche group led by Cruz Cárdenas, which has been illegally usurping and occupying protected areas of Los Alerces National Park since 2020, will proceed." They announced that the operation would be carried out with Federal Forces.

They also alluded to the "right to property of the National State" and alleged verbal and physical attacks by the community. And they referred to Law 26.160: "legislation promoted by previous administrations, which suspended the execution of evictions in territories claimed by certain groups," thus disregarding the rights of indigenous peoples in Argentina.

Identity is a right

Nora Rodriguez and Raul Mazzone, members of the APDH (Permanent Assembly for Human Rights) present at the press conference, stated: “It is horrifying to see the racist, colonial, and increasingly inquisitorial face of the state, which enables methods that were prohibited during the dictatorship, conducting investigations as if there were internal enemies. It is a horrific aspect of the state. But at the same time, we see identity processes unfolding in communities, which are a right. Dispossessing them of their territories is very painful. We see the damage this causes to people of different genders and ages, to children who will suffer this significantly throughout their lives. Identity is a right; perhaps the state, in its current form, doesn't like to acknowledge it .

In turn, the Argentine League for Human Rights stated: “Why did we elect a democratic government, including indigenous peoples? We have the right to question that government; no government is absolute. Shouldn't the current administration respect the Argentine Constitution? Today we see a state that fosters discrimination.”

The National Team of Indigenous Pastoral Care (Endepa) stated in a press release: “The eviction of the community reminds us of recent dark episodes in which those involved in territorial claims lost their lives. It is possible to build an intercultural dialogue in which all cultures and peoples are respected, but this will not happen if the state's response is violence, discrimination, and a lack of respect for the collective rights of pre-existing communities.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.