Soledad Cañumil, Mapuche lifeguard: Reclaiming the autonomy of our bodies and territories

Soledad Cañumil, a teacher, first responder, and Mapuche woman, talks about the challenges of intercultural feminism and her experience accompanying women through abortions.

Share

“I support women seeking abortions, and I identify as Mapuche. But I don't conflate these two things. I don't support women seeking abortions as a Mapuche woman; I support them as a feminist activist. Our activism intersects, but they are two distinct issues.” Soledad Cañumil makes this initial clarification, as a starting point for separate paths. But later, as the days and conversations unfold, these seemingly distinct worlds will begin to intertwine.

Abortions are a part of her daily life: she is a member of Socorro Rosa Rabiosa , a feminist collective that supports people in southern Chubut and Santa Cruz provinces who have decided to terminate their pregnancies, ensuring they do so with information and in a safe and caring manner. She is also a member of Socorristas en Red , a federal network of feminist collectives in Argentina that has been supporting thousands of abortion processes since 2012, eight years before the passage of the Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy Law . Through her feminist activism, she also began working within the History Department at the National University of Patagonia San Juan Bosco. There, she was very active in the student union, advocating for various gender-related issues: the implementation of protocols, prevention programs, and the eradication of violence. She lives and works as a high school teacher in Comodoro Rivadavia.

“I’m primarily interested in education,” she says. “I’m always fighting for these topics to be more integrated into the formal education system, into curricula, programs, and courses. I consider myself an advocate for public education, comprehensive sex education, and now, intercultural education. And I’ve been providing abortion support for over seven years .”

– And how did you come to recognize yourself as Mapuche?

– I can't pinpoint a moment when I said, "I recognize myself." My last name is Cañumil, so I always knew in some way that I was Mapuche; it wasn't something unknown. My father comes from Río Mayo, a town in central Chubut. When I was little, I heard him speak, a few words in Mapuzungun , some memories. I always had that knowledge. But accepting it, recognizing myself, and beginning to recover that identity came hand in hand with my time at university, the public education system, and specifically with a degree in History.

Recovering indigenous identity is not easy

The conquest of America, the Desert Campaigns, the indigenous genocide upon which the American states were founded. The encroachment upon indigenous bodies and territories. All this and much more he learned thanks to the public university, where he met other people in the urban environment who already identified as Mapuche. And there, another path began.

“It’s difficult to talk about this,” confesses the history professor. “Those of us who were born and raised in cities have lost a large part of our personal and family histories, also due to forced displacement. So we are Mapuche, but we don’t have much knowledge of our culture and our identity. We have to recover it; we are learning with others. I call it a personal process of identity recovery.”

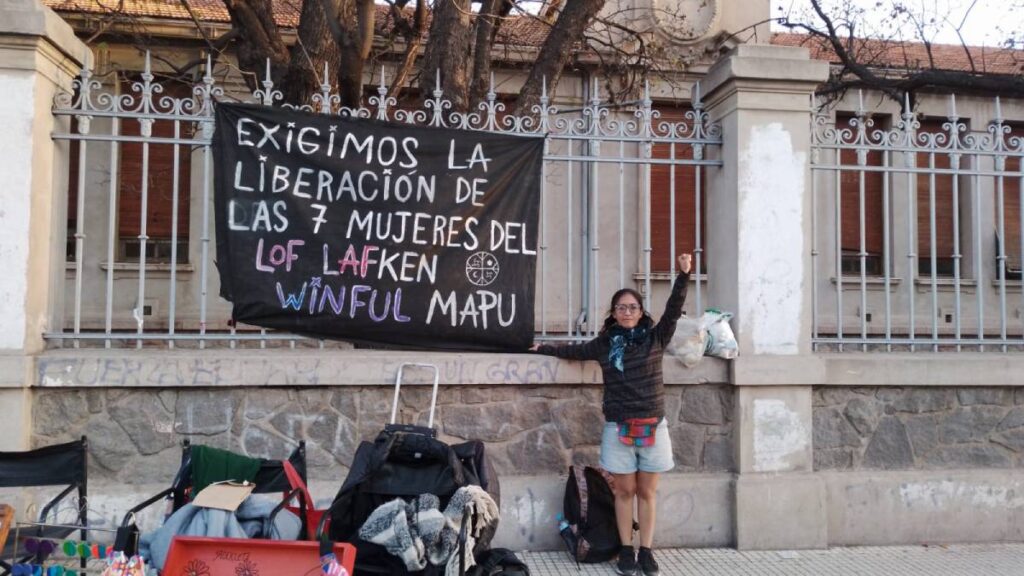

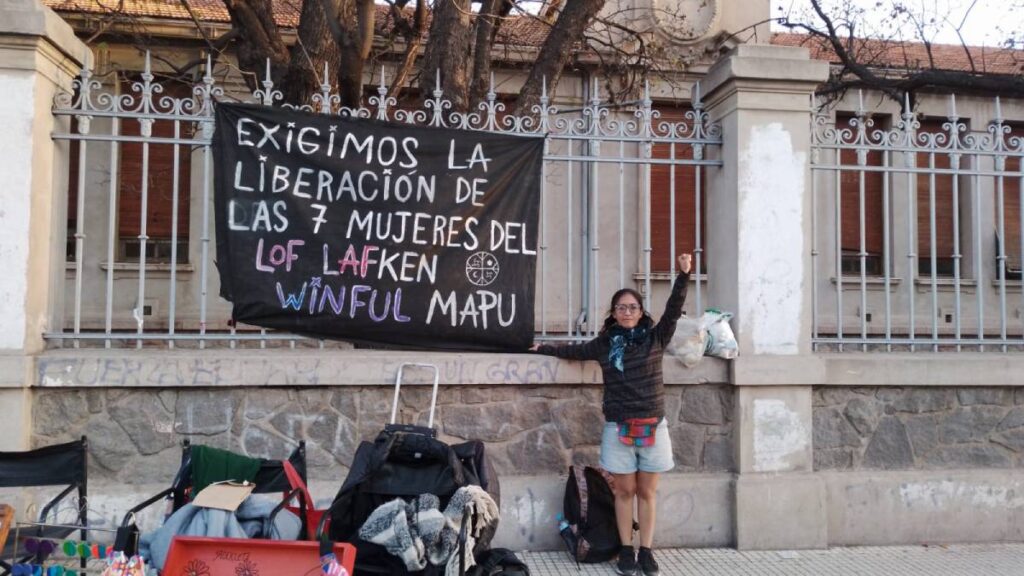

In 2016, the escalation of the historical persecution and harassment of Indigenous communities in relation to land reclamations—under President Mauricio Macri and Minister of Security Patricia Bullrich—further fueled this personal quest. She became involved in various struggles, putting her body on the line to raise awareness, demand change, and spread the word. And in 2021, she began to participate from a spiritual perspective.

“It’s one thing to recognize yourself, and another thing to be recognized by the communities and other members of our people,” she clarifies. “Being recognized is a different process. For me, that’s where an approach to other spaces began, spaces where people who aren’t from the community don’t participate, for example, ceremonies like the winoy xipantu and other celebrations.”

A decisive ruling in the fight for abortion rights

In 2010, Comodoro Rivadavia was the site of the landmark FAL ruling , a decisive precedent in the fight for abortion rights. A 15-year-old girl from that city was raped by her stepfather, a member of the Chubut police force. Her mother appealed to the courts to allow her to terminate the pregnancy. After being rejected at various levels, the Superior Court of Justice of Chubut ruled that the act was not punishable under Article 86 of the National Penal Code and finally permitted the procedure when the girl was 20 weeks pregnant. In 2012, the Supreme Court upheld the ruling, stating that such cases should not be subject to judicial review.

Four years later, Soledad and other women from that city began to educate themselves and disseminate their views. And so, quite naturally, this feminist group became a point of reference for many people who wanted to know how to access abortion. In times of secrecy, they built trust and created a space where these questions could arise. This led them to train in abortion support. It was a year of reading, discussion, debate, and some initial experiences until they formed the Socorro Rosa Rabiosa collective and decided to join Socorristas en Red (Network of Abortion Supporters). A new path, a new collective challenge.

Paths that intertwine

“Today, after so many years, we engage in self-criticism,” says the Mapuche activist, and asks herself: “Perhaps we entered feminism from more youthful perspectives, from white culture, right? From more Western perspectives. We are not only women, Argentina is not white, and we are in a territory that is Mapuche-Tehuelche.”.

Soledad has always participated in autonomous spaces: at the university, in feminist struggles, and in Mapuche struggles. “I strongly advocate for spaces that we haven’t created for any political party,” she says, adding, “Now that I think about it, autonomy of bodies and territories—everything intersects and connects.”.

In Socorro Rosa Rabiosa, there are several members who have identified as Mapuche, a non-binary member who has come to identify as Afro-descendant, and a member from Salta who is also undergoing a process of reclaiming their Indigenous identity. It is no coincidence that they choose to join a collective that provides a space for these new forms of self-determination to emerge.

Intercultural abortion as a utopia

“What’s at stake in abortions are, ultimately, life stories,” the teacher reflects. “So, the other person is sharing their personal story with us, and that’s very gratifying. And I really value that trust. Calling a number you don’t know what’s behind it, and calling anyway because someone recommended it. Or because you read something that gave you that trust.” For Soledad, it’s important to clarify that she doesn’t practice “ Mapuche health ” because she doesn’t consider herself qualified for that. Meanwhile, Socorro Rosa Rabiosa doesn’t ask about the ethnic identity of people seeking support to terminate a pregnancy. Neither does the National Sexual Health Hotline, 0800-222-3444 . What would happen if those questions were asked? Could they lead to new approaches?

As a first responder, Soledad accompanied some Indigenous people, but she didn't need to translate information into other languages or consider cultural adaptations. However, she hopes that abortion will be feminist and intercultural.

In that sense, and as a good teacher, she offers a historical analysis of the perspective on health: “The medicine we know today was founded by nation-states and the capitalist system. All peoples have had their own health practices, their own medicine. And they took it from us, appropriated it, and sought to exterminate it, with all the historical appropriation they have made of bodies.”.

The worldview of a territory to be cared for

For her, “it is very clear that there are other forms of knowledge and other ways of understanding health and other ways of understanding the body. And I say this from what little I know of my Mapuche culture and also from feminism, which also problematizes those only validated forms of knowledge.”.

Furthermore, the activist maintains that “in some communities, abortions are performed using methods other than medication. This is happening. It's not very visible, but perhaps the necessary dialogues, conversations, and spaces for dialogue haven't yet taken place. And today, with the prevailing fascism, it's very difficult to protect all of this without putting oneself at risk.”.

“I find it extremely difficult to deal with racist spaces,” she continues, “that ignore the fact that our country was founded on the genocide of certain peoples. That are ignorant of the history of the imposition of capitalism, the system that is starving us, plundering us, polluting our lands, and taking away our water. And it is precisely the Indigenous peoples who are challenging very powerful interests. What we seek in this territory, which is ours, is to protect it.”

Safe abortions. Caring for the body. Caring for the land. Care is a recurring theme throughout the narrative. “You won’t find people from our community setting fire to forests. Or thinking about building a hydroelectric dam, or only thinking about appropriating something for profit. Therein lies a question of how we understand the world and its relationships. We are not only human; we need to recognize all forms of life. We question this system, and the system responds with violence, harassment, and criminalization.”.

“I see it as a Mapuche person and as a feminist”

The passage of Law 27.610 is undoubtedly a historic milestone in the feminist struggle, but Soledad warns that “we need to protect it, but we also need to keep thinking about how to better guarantee it. And I say this from my contact with people who have abortions: the violence of doctors, the mistreatment, the racism, what happens to migrant women… Obstacles, difficulties, barriers. In these years since the law was passed, there has been a reconfiguration, and we have once again fallen under the control of doctors: we are again dealing with having to see a doctor four times just to access an abortion.”.

The interviewee looked for personal images to illustrate this article, but found almost no photos where she is alone: with few exceptions, she always appears with other people, in the streets, in classrooms, with the green scarf or a kultrun .

For her, “a feminism that only addresses gender violence and doesn't question capitalism, extractivism, or racism is a feminism that isn't problematizing anything.” And there, autonomy emerges as the thread that links the sovereignty of bodies and territories. “We will be able to exercise our bodily and territorial autonomy if we can decide. I see it as a Mapuche woman and as a feminist. The fight for abortion rights has been about reclaiming our life projects.”.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.