The story of two LGBT activists and feminist journalists fighting for marriage equality in Peru

Graciela and Dayanna had to get married in Argentina and then filed a lawsuit with the courts to register their marriage. "We've been doing activism for years, but we haven't made much progress on LGBTQ+ issues."

Share

LIMA, Peru. As the plane carrying them back to Peru began its ascent, Graciela and Dayanna looked at each other and wept. They knew they were returning to a country hostile to LGBTQ+ people. Their recent marriage in Buenos Aires would not be legally recognized and, moreover, would be questioned. They wouldn't be able to kiss or hug in the streets without risking their lives. Their love, their longing to see their families, and their desire to fight for LGBTQ+ rights in their homeland gave them the strength to return.

Graciela Tiburcio Loayza, bisexual, and Dayanna Delgado Velasco, lesbian, both 32-year-old journalists, feminists, and activists, were married on May 3, 2023, in Argentina. However, the Peruvian state does not recognize same-sex marriage. Peru continues to deny LGBTQ+ couples the right to be recognized as families.

On their first wedding anniversary , May 3, 2024, Graciela and Dayanna, accompanied by their families and lawyers from the Flora Tristán Peruvian Women's Center, filed a petition with the Peruvian Judiciary to register their marriage in Peru. Many photos were taken that day in front of the courthouse. In one, Graciela's mother holds a portrait of her husband and Graciela's father, who sadly passed away in 2022. It is the same photograph the couple has in their living room.

“ Having our family on our side makes us feel like we’re not alone in this process. We recognize this privilege,” Dayanna tells Agencia Presentes , sitting with her wife in their apartment living room. “ We’ve been doing activism for years, but we haven’t seen much progress on LGBTQ+ issues. The recognition of our marriage represents the recognition of other LGBTQ+ marriages ,” Dayanna affirms.

their marriage before the Judicial Branch.

When the NGO Flora Tristán announced on social media and Facebook the start of the legal process to recognize their marriage, the networks were flooded with LGBT hate comments. They are aware of the risks they face and try to mitigate them. One of their protective measures is not posting photos of their locations. “ I feel that the current social context is more aggressive towards LGBTQ+ people. Now there is so much hatred perpetuated by the authorities that people no longer hold back or they attack you ,” Graciela says.

No rights for same-sex couples

Among the few LGBTQ+ individuals who have decided to fight the Peruvian justice system to register their marriages, several have had their rights violated by the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (RENIEC) , the Judiciary, and the Constitutional Court (TC). For this reason, they have turned to international bodies. These institutions are trampling on the human right to equality that the Peruvian State is obligated to guarantee.

Without marriage equality, LGBTQ+ couples cannot access shared health insurance, the right to make decisions about each other's medical care, widow's pensions, and other benefits. “Graciela is self-employed. I have health insurance through my job, but I can't list her as my spouse on the policy. Many diverse families experience the same thing. Those with children face even greater vulnerability,” says Dayanna.

The couple's lawyer, Cecibel Jiménez, explained to Agencia Presentes that they decided to pursue the civil route because they have a history of not obtaining favorable rulings through the constitutional route . "In the constitutional route, it will always end up being reviewed by the Constitutional Court. At least until now, the Constitutional Court's approach has been to not rule in favor of same-sex couples," she said.

For Liz Meléndez, director of Flora Tristán, this lawsuit also seeks to set a precedent highlighting the need for clearer and more efficient mechanisms so that other same-sex couples who wish to formally unite their lives in marriage can register their unions and thus enjoy the same rights as anyone else . “We also seek recognition of marriage equality between people of the same sex ,” she emphasizes to Presentes.

Difficult childhoods and fighting spirit

Graciela is an only child. She lived until she was eight years old in San Isidro, one of Lima's most exclusive districts, where her family owned a restaurant. She studied at the María de las Mercedes school in Miraflores, another affluent district of the capital. As a result of the political crisis that gripped the country in the 1990s and 2000s, when former dictator Alberto Fujimori fled Peru, businesses began to collapse, including her family's.

They moved to the Villa María del Triunfo district. “The way I was treated at school changed. A teacher told me I should go to a school in my own neighborhood. My circle of friends drifted away. I was one of the few dark-skinned students. I was never aware of my skin color because the money I had whitened . When I lost that money, the blow hit hard,” Graciela says. “I went from being a girl who had many comforts to selling clothes at the market. Sometimes we didn't have enough to eat.”

Dayanna was born in Lima. She has one sister and three brothers. When she turned four, her father got a job in Trujillo, a province in northern Peru. There they lived in a rented space two meters wide, “like a matchbox,” Dayanna says. After a few years, her father lost his job. To help him, she and her siblings sold candy in Trujillo’s main square. “Those were hard times, but we also remember them fondly. We did that for six months,” she recounts.

In 2021, the wives traveled to Trujillo. Dayanna showed her the little house where she had lived. “The fact that she took me to where she had been in her childhood, even enduring hardship, but also remembering all the beautiful things, made me feel like, ‘Wow, how I admire this woman!’” says Graciela. “It’s mutual,” Dayanna says, looking at her with love.

Both believe that their childhood experiences were a great impetus for their fervent activism in support of the causes they believe in.

How to become an activist

They met in 2013 at Jaime Bausate y Meza University, where they studied journalism. They fell in love after graduating. “I remember Graciela as very sweet back then, with her giant flower hair clip,” says Dayanna. “Daya was an activist at the university, and I thought, wow, that’s so cool, and on top of that, she works and pays for her own studies ,” says Graciela.

At university, Graciela had a romantic relationship with her best friend, who is now non-binary. She supported her ex-girlfriend through her transition. During that relationship, she became involved in activism. “I saw this person struggling with a huge internal battle. I decided to look for groups that could help her with her transition.”

On May 17, the International Day Against Homophobia, she went with her ex-boyfriend to an Amnesty International (AI) event. From that day on, Graciela volunteered for various organizations and collectives. At 25, she was elected president of AI.

Dayanna's first steps into activism were as a journalism student. With a classmate, she created a university collective, Bausate Diversa. They felt there was a lack of respect and open dialogue surrounding the LGBTQ+ community. Their first activity was called Free Hugs Against Homophobia. “We painted the phrase on small signs and went all over the university. After that, many people wanted to join the collective, and we started organizing discussions,” Dayanna recounts. Today, she works as a recruitment coordinator at Amnesty International.

After graduating in 2019, Dayanna ran into Graciela wearing ripped jeans and wielding a giant megaphone, speaking out against some professors as part of an activity organized by Bausate sin Acoso (Bausate Without Harassment), a collective that denounces and supports victims of sexual harassment at Jaime Bausate y Meza University. “I knew she was an activist, but I hadn’t seen her in a while, and it was a shock. I saw her and thought, ‘ She’s my friend, ’” Dayanna recounts.

On March 8, 2020, after the Women's Day march, they went dancing at a bar with other friends. They spent the early morning at a friend's house, talking and looking at each other. The next day, Dayanna called her to say that "they needed to talk about last night." Graciela replied, "I like you," and Dayanna responded, "You too."

A few days later, the government declared mandatory social isolation due to the pandemic, and they couldn't see each other. The beginning of their relationship was entirely virtual. In 2021, they moved in together.

“May everything continue to go well for us.”

One night in August 2022, Dayanna went to pick up the ring she had ordered to propose to Graciela. It was a surprise. That day, Graciela's parents were waiting for her to celebrate a professional achievement. Her father made a toast: "May everything continue to go well for us." The next day, she died of a stroke.

“The following days were quite painful. Graciela was very unwell. One day I saw her lying sadly on the couch, completely unconcerned about everything, and I thought, ‘That’s enough.’ I took out the ring and told her that I understood she was going through a very difficult time, but that her father would have wanted her to continue thinking about her future,” Dayanna recounts. Graciela was moved and told her that of course she wanted to marry her.

Months later, they got married in Argentina. They thought about bringing their mothers, but they didn't have enough money. "The final part of my vows, where I say 'may no one ever be missing from our lives,' I said it for my dad, and then 'may everything continue to go well for us,' I also said it for him. We felt it was his last wish without knowing it," Graciela shares.

Leaving the civil registry, they went to the notary to begin the process of obtaining the Hague Apostille, a requirement that any marriage celebrated abroad needs to be registered in its country of origin.

In their living room hangs a picture of an activist grandmother holding a sign that reads, “I’m the grandmother of the girl you’ll never touch.” Like her, they envision growing old together, still active in the community. “We would love to grow old and have our marriage recognized, alongside the marriages that already exist and those that will come after,” says Dayanna.

Same-sex marriage: a struggle with stories

Three same-sex couples who have made their fight for the legalization of their marriage visible in Peru have turned to international bodies to access the justice they have not been able to obtain in their country.

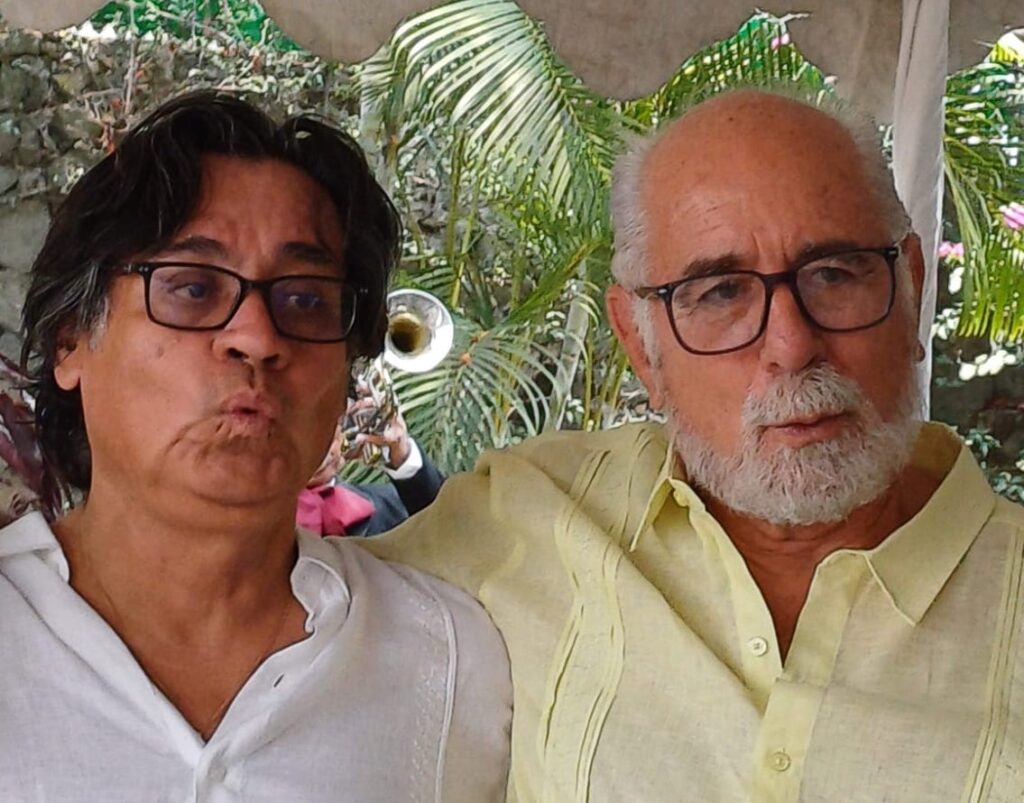

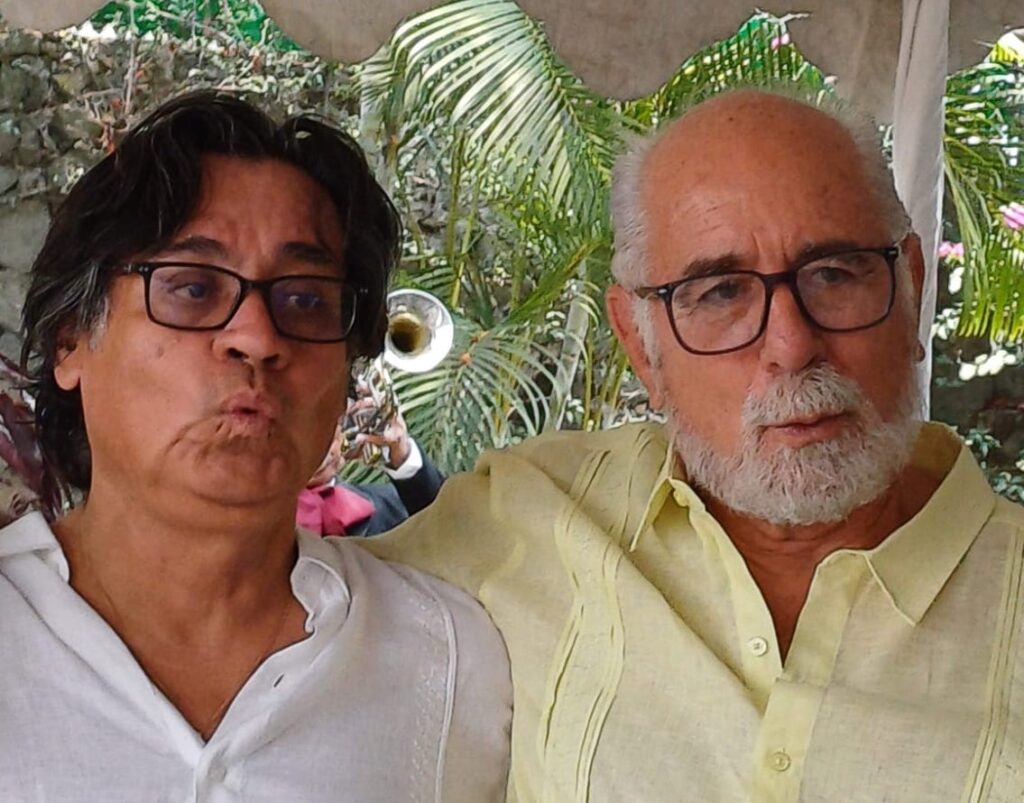

Óscar Ugarteche: “I am going to sue the Peruvian State for moral damages”

The founder of the Lima Homosexual Movement, Óscar Ugarteche, married Mexican national Fidel Atoche in 2010 in Mexico. In 2012, he attempted to register his marriage in Peru with the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (Reniec), which rejected his request. Óscar sued the institution. In 2016, in a landmark ruling, the Seventh Constitutional Court of Lima ordered Reniec to register his marriage. However, Reniec appealed, and the case went to the Constitutional Court, which rejected the lawsuit seeking to compel Reniec to register his marriage.

In an interview with Agencia Presentes , Óscar stated that he and his husband went to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to demand that the Peruvian State comply with its international commitments. “But Peru told the commission that it was not applicable. Now we are before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights , and we are going to win there, but surely the Peruvian State will not recognize it. We will file a lawsuit against them for moral damages and for a huge sum.”

Susel and Gracia : at the IACHR

similar case involved Peruvian congresswoman Susel Paredes and her wife Gracia Aljovín . They married in the United States in 2016. The Peruvian National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (Reniec) rejected their application twice. The couple filed a constitutional appeal, which the court ruled in their favor in the first instance. However, in 2022, the Constitutional Court (TC) declared that the registration of their marriage was not valid.

According to the 2023 LGBTI Annual Report by the NGO Promsex, they are awaiting a ruling from the IACHR .

Andree and Diego: 10 years of marriage for the world

Peruvians Andree Martinot and Diego Urbina married abroad and suffered the same injustice in their country. “The Constitutional Court ultimately denied our claim. Our case is now before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. We've been officially married for 10 years in the eyes of the world, but not in Peru Andree told Presentes

Noam has two moms

Mabel Aguilar, president of the Peruvian Association of Homoparental Families, and Luisa Morcos, the association's head of institutional relations and fundraising, have a son, Noam, who turns four in August. On the child's national identity document (DNI), only Mabel is listed as a single mother, since there is no law in Peru stating that two mothers or two fathers can have children. The mothers want Noam to be legally recognized as the son of both of them. Their lawyer advised them to register their marriage first. They had to expedite their wedding, which took place in August of last year in Arica, Chile, and applied for registration with the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (Reniec) in March 2024. Months passed because they were delayed in receiving the Hague Convention apostille.

The lawyer is requesting the registration of the marriage, as well as other legal actions to ensure that Luisa has certain rights over Noam, such as permission to travel with him, the authority to conduct business at various institutions, make a will, among others. “We are fighting so that Noam won't have problems in the future if one of us is no longer there,” Mabel told Presentes .

On their wedding day, they had their picture taken at the civil registry in Arica, in front of an archway adorned with colorful flowers. In the picture, Luisa is hugging Mabel, who is holding Noam, and he's holding up the family record book they were given as if it were a soccer trophy, his little eyes gazing at it with pure joy. "Whenever Noam sees the photo, he says, 'Here are my moms when they got married.' We feel like he understands the important step we were taking," Mabel shares.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.