1. In the first person: Gastón on the couch with God

In his teens, Gastón turned to Catholicism to work in the most vulnerable neighborhoods. This is the story of how he ended up in a "healing" camp and also how he retraced his steps and became a psychologist.

Share

Gastón Onetto is 38 years old, a psychologist, and lives in the city of Santa Fe. He doesn't come from a religious family, but as a teenager, he became involved with Catholicism because he wanted to work in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods of the provincial capital. He enjoyed helping out at the soup kitchen, tutoring, and playing with the children in the Los Troncos and Loyola Sur neighborhoods.

In 2004, shortly after beginning her Psychology studies at the Catholic University of Santa Fe, she decided to start therapy. At that time, she was involved in an ecumenical group that combined social work with youth gatherings. It was there that a classmate recommended an evangelical psychologist from Rosario who traveled weekly to the provincial capital. So she contacted him and began having regular sessions with him.

For Gastón, talking about God, sharing thoughts related to religious beliefs, and praying were part of his daily life. He studied at a Catholic university and dedicated much of his time to the Christian work offered by the groups he participated in. Therefore, at first, it didn't strike him as odd that the professional mixed religious concepts into his analyses.

“In the third session, I told him I was seeing a boy. He was surprised and began, not so subtly, to launch into a discourse in which he constructed the problem he called 'gender breakdown.' For about six months, he kept recommending books and notes that mixed pseudo-psychology and religion,” Gastón recalls, adding: “I think my membership in the church left me vulnerable. He spoke to me in that code where we understood each other, and it wasn't strange to me anymore. If someone else were to hear about God in therapy, it would seem very odd.”

Gastón knew that homosexuality wasn't well-received in religious circles. But he understood it more as a moral stance, which didn't curtail his desires or prevent him from experimenting. "When the psychologist put together all those arguments, the perception of homosexuality as an illness was constructed for the first time for me. That's when I bought into that idea," he explains.

That break led him to "cut off the gay lifestyle." This meant changing the way he dressed, the way he sat, giving up certain music, and distancing himself from friends. He traded the Spice Girls for Jesús Adrián Romero—a Mexican singer-songwriter and pastor with nearly two and a half million monthly listeners on Spotify—and Marcos Witt—an American singer and pastor who has won five Latin Grammys for Best Christian Album.

“Renew me, Lord Jesus. I don’t want to be the same anymore. Renew me, Lord Jesus. Put your heart in me. Because everything inside me needs to be changed, Lord,” Witt sings in one of his best-known songs.

The psychologist's explanations resonated with Gastón's subjectivity and "sounded interesting because they were interwoven with certain psychological theories." As the sessions continued, his social circle shrank. Eventually, he could only speak with two female friends and one male friend who belonged to the same religious group as him.

“They started telling me I looked bad, that my smile had disappeared. It was very important to me that they told me to just be myself because they were very religious. They were the ones who supported me,” she says. She also remembers that her therapist advised her not to tell her family what was happening to her “because they don’t share the union in Christ” and wouldn’t understand.

A week to change

Gastón was feeling increasingly worse and began to doubt the effectiveness of the therapy. After his therapist recommended he see a psychiatrist, there was a first breakdown. That's when he was offered the opportunity to participate in a camp for "people going through the same thing as him."

Being admitted wasn't easy. Besides requiring the payment of a hefty registration fee, it required a recommendation from a professional and a religious figure. So Gastón went to talk to his family to get the money and returned to the Catholic church in his neighborhood to ask the priest to send the letter that allowed him to enter.

That's how, in 2005, Gastón arrived at a hotel in La Falda (Córdoba), along with dozens of young people from different provinces and exhibitors from all over the Americas. Although another young man also traveled from Santa Fe, they weren't allowed to ride on the same bus or meet each other. During the week of the event, they were forbidden from saying their names or sharing any contact information.

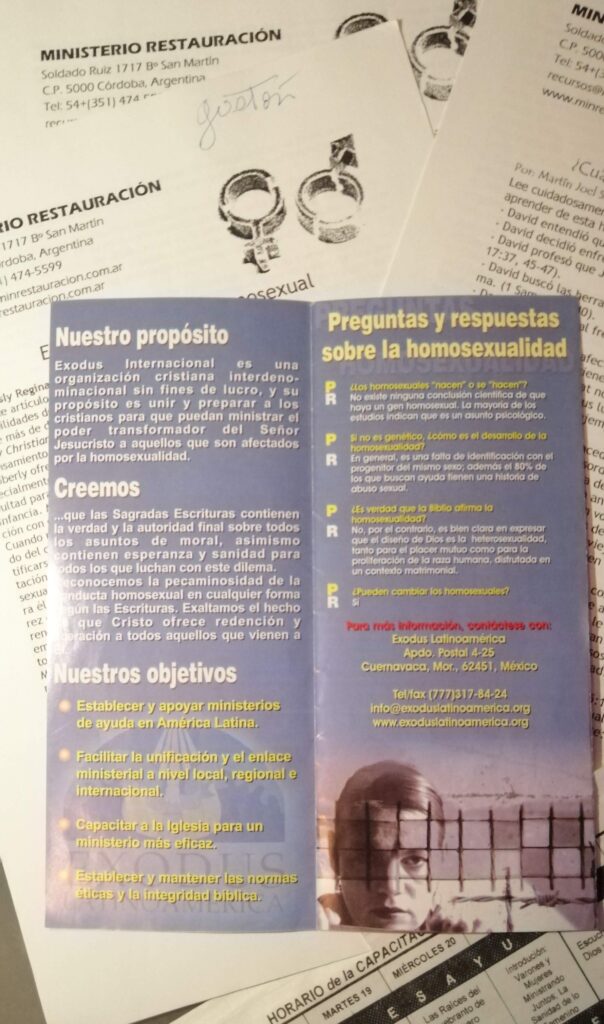

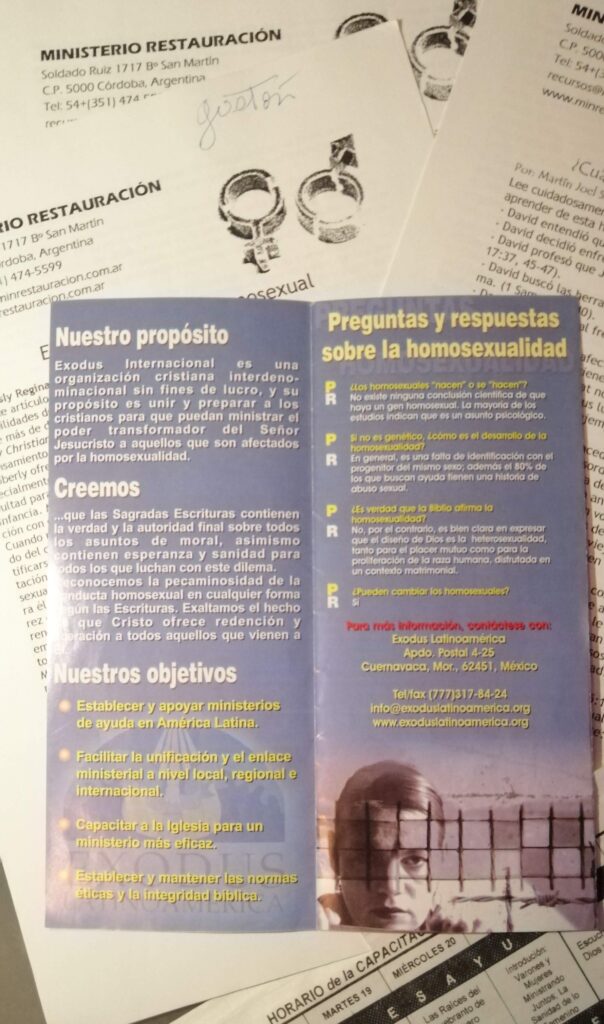

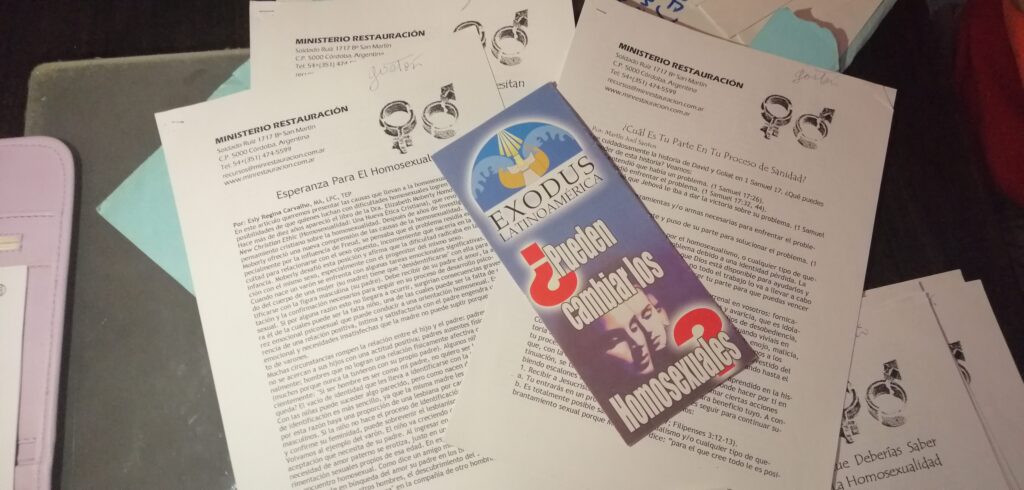

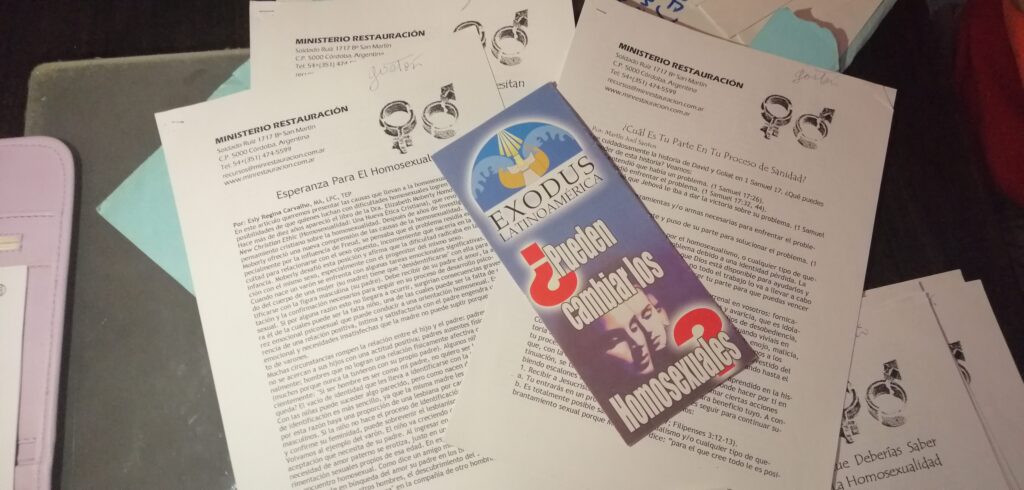

Upon arriving in La Falda and completing their registration, each person received instructions on where to sleep and what activities to participate in. From Monday to Saturday, there were talks given by representatives of the organizations that sponsored the gathering—including the aforementioned Ministry of Restoration and Exodus—followed by smaller group sessions where experiences were shared and prayers were offered.

Healing the maternal wound, healing the paternal wound, the breakdown of gender roles, sex addiction, and victims of sexual abuse were some of the central themes of the presentations. There wasn't much free time. And the fear and guilt imposed on them regarding sexuality created isolation among the participants.

Today, having retraced that path and with The Cure—a play that helped him process his experiences—he recalls situations with greater distance and humor. There are many anecdotes he reconstructs from that trip, like the time a man spoke up and said, “I want to report that a young man took off his shirt in the room. We’re all in the process of healing, we need to be more careful!”

Gastón shared the room with two other men. One was an older hairdresser who told him he was one of the founders of La Piaf (the first gay bar in Córdoba). Before going to sleep, he asked them to pray: “Lord, we ask that tonight you come and restore us; we are here confirming your presence,” he said solemnly, but then his tone changed to a more conspiratorial one, adding: “Because if it had been another night, oh boy. But not now, Lord.”

A few days had passed since the camp, and his discomfort grew to such an extent that he asked to leave. At first, they refused, delayed him, and tried to convince him that he had to keep trying to change . But he returned home with one conviction: he had to stop therapy and all those imposed activities.

At first they refused, delayed him, and tried to convince him that he had to keep trying to change . But he returned home with one conviction: he had to quit therapy and all those imposed activities.

Days later, she sat down to practice what she was going to say to her psychologist. She wrote it down on a piece of paper, repeated it aloud to bolster her courage, and went to the next session certain it would be her last. When she arrived for her appointment with the psychologist, she said:

I don't know if God exists. And if He does, I have a more loving image of Him, that He will love us as we are and perhaps doesn't even want us to change. What's more, I don't know if this can be changed.

the look on the professional's when he finished speaking. Nor will he forget the response.

"You're jeopardizing your eternal salvation by sowing these doubts. Are you going to be a psychologist? How can a blind man lead another blind man?"

From then on, Gastón distanced himself from religion and reconnected with his gay friends. They, he says today, helped him heal the most difficult thing: his self-image.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.