Mina Morsán: "It sounds like magical realism, but the jungle is resisting the train that isn't Mayan."

Mina Morsán, an activist, explains from Yucatán why organizations defending the territory are resisting the Maya Train megaproject and what the anticipated risks are that are beginning to materialize.

Share

MERIDA, Mexico. The Maya Train is a megaproject being promoted by the Mexican government and generating protests from environmentalists: 42 trains that traverse 1,525 km of railway tracks through the southern states of Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo. This involves, among other things, crossing one of the most important rainforests in Latin America and drilling into the cenote caves of the Yucatán Peninsula.

Since its announcement in 2018, civil society organizations, researchers in anthropology and the exact and social sciences, human rights defenders, and Mayan communities have protested the project's various irregularities. These range from the lack of free, prior, and informed public consultation with the communities to its environmental impact. Operated by a public company, Olmeca-Maya-Mexica, the train will offer differentiated services: it will be a tourist train, a passenger train, and a freight train.

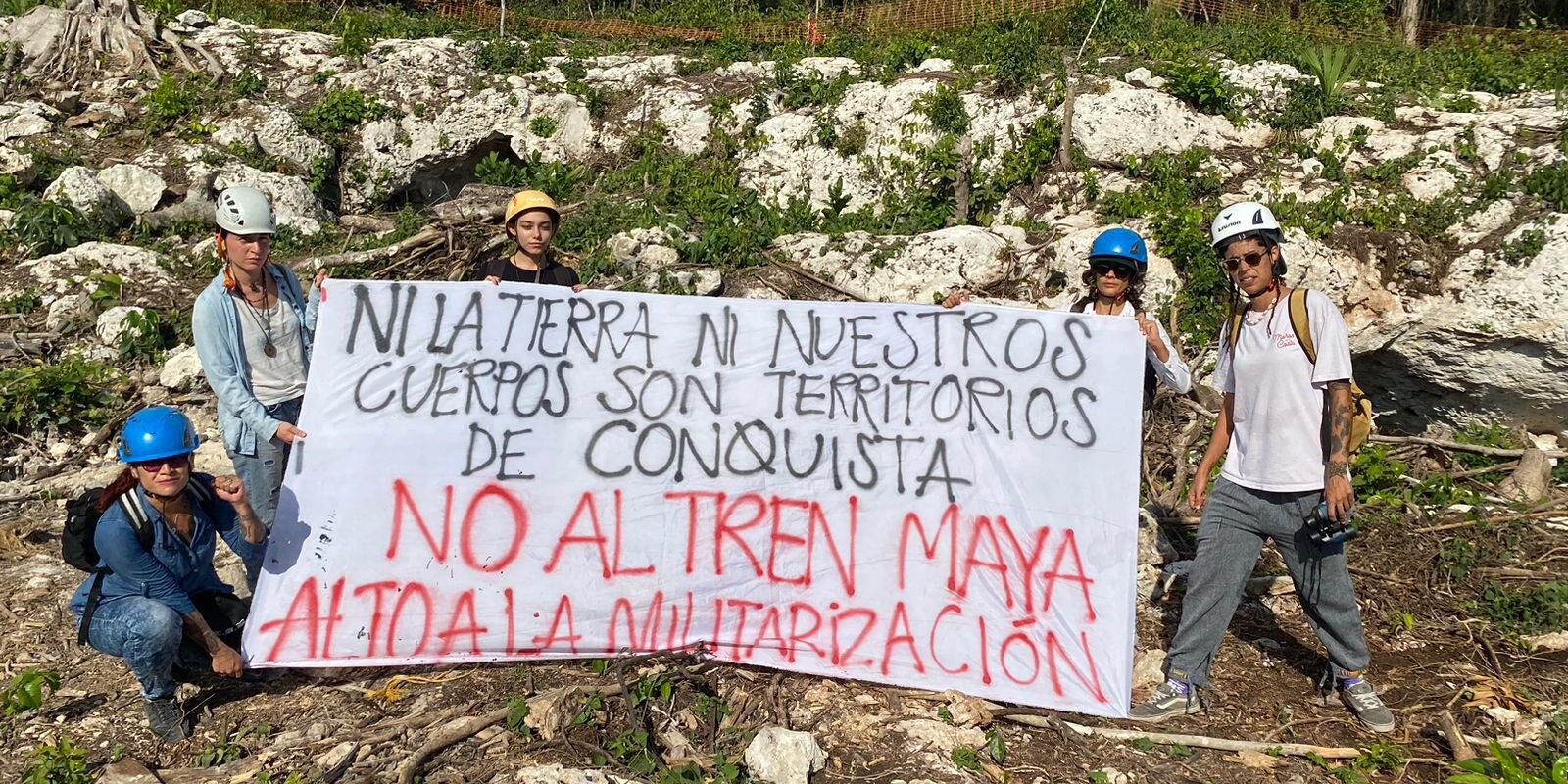

Mina Morsán—pictured standing in the opening photo wearing a blue helmet—is a diver who lives in Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, and is a member of the SOS Cenotes organization, Mujer Libre Mx (MULI), and the Red de Resistencias Sur Sureste (South-Southeast Resistance Network). These are just a few of the many groups that have protested against the megaproject from various perspectives: anti-military, gender-based, environmental, anti-racist, architectural, and civil engineering.

What imminent risks does the Maya Train pose?

The first concerns about the project on the Peninsula were raised at the International Gathering of Women Who Struggle—organized by the Zapatista women—in 2019, before the pandemic. Mina Morsán, originally from Guadalajara, had just moved to Quintana Roo when the project was announced. “It was like when you’re told someone has cancer. The first thing you think about is how much time they have left.”

In an interview with Presentes, Morsán argues that the greatest risk posed by the Maya Train is not over-tourism—one of many risks—but rather the industrialization that the megaproject will bring . In recent years, southeastern Yucatán has been overexploited by mega-pig farms and the real estate industry, which fail to consider the region's soil type: porous and riddled with underground caves where pollutants enter and exit unfiltered.

“The Maya Train widens that door. Communities have been fighting against these industries for 10 or 20 years. And in the official communication about the Train, they talk about boosting these industries, using euphemisms. The territories lose out with industrialization, and a territory as fragile as this one loses even more, ” explained Mina Morsán.

The train that is not Mayan

In the hands of a public company, Olmeca-Maya-Mexica, the train will offer differentiated services: it will be a tourist train, a passenger train, and a freight train, seeking to connect southern Mexico. But Quintana Roo is a state on the Peninsula where Mayan communities have been displaced and tourism has exploited their indigenous culture. It is also a place that attracts biologists, explorers, scientists, and conservation experts because of the natural wealth of its sea, jungle, and cenotes. Therefore, when representatives from the National Fund for Tourism Development (Fonatur) arrived—the agency that administered the project until it was taken over by the military, where it remains today—the Mayan communities and specialists raised the alarm.

"There used to be an office in charge of promoting the project. We had a couple of meetings and it became clear to us that they would use euphemisms. Even when they were being heavily criticized for the data and information they were hiding or downplaying, they responded with a smile. They were questioned from many quarters: engineers, architects, cave divers, lawyers talking about the right to a healthy environment. But it was useless."

One of the most controversial decisions regarding the route of the Maya Train is that of sections 5 and 6 in Quintana Roo . Initially, those in charge proposed that the train would cross the highway to avoid further deforestation. This angered hotel owners. So they decided to pass over the jungle and cenotes. They built concrete pilings that pierce caves and fragile ecosystems.

“These ideas could only occur to people who don’t know the area. To those who have no idea that drilling into caves with pilings will eventually cause them to collapse. We know it’s going to fall; we don’t know if it will be in two weeks, four months, or a few years, but it’s going to happen. Now that it’s a widely publicized and obvious absurdity, they’re changing the opening date ,” says Morsán.

In resistors

The pandemic slowed the project's progress, but visible advances only began in 2021. By then, collectives and networks of people were already questioning the train. Everything became more real when they cut down the ceiba trees, those large and sacred trees of the Mayan people , and began removing the lighting and drilling into the road .

In November 2022, a massive call went out to towns and urban and rural communities throughout the Maya territory to travel to Xpujil, Campeche. More than 15 organizations and collectives arrived, forming the South-Southeast Resistance Network to defend the life of their territories. They reunited for the Southern-Resist Caravan, which began on the coast of Chiapas, and connected with other organizations also resisting the Trans-Isthmus Corridor.

" We realized the level of militarization in the country . There were a lot of checkpoints manned by the National Guard, the Army, and the National Migration Institute. It's terrifying that the US agenda of building security from a military perspective, rather than from a human rights perspective, is back."

The caravan from the South Resists found many organized groups in the southern states of Oaxaca, Tabasco, Chiapas, Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Yucatán. However, they also encountered environmental disasters, such as in the El Bosque area of Tabasco, now flooded and devastated by the climate crisis.

“It was a powerful and inspiring journey. Everywhere we went, we encountered a fiery force. Even in the land of Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, there is resistance to the Maya Train ,” says Morsán.

Impacts on women, children, older adults, and LGBT people

Organizations like Mujer Libre Mx (MULI)—of which Morsán is a member—have denounced the differentiated impacts of the Maya Train megaproject on each population group: women, children, the elderly, and the LGBT community. Since the project began, they have received reports of missing women and femicides. What is the connection to this? “When the military enters a territory, they bring with them a lot of weapons and masculine dynamics that pose a risk to women and LGBT people. It’s a ticking time bomb. Many of our colleagues no longer dare to go out at night because of the military. So far, we haven’t had any cases of military aggression against the LGBT community, but I don’t rule them out because it’s a very hostile environment. For example, young people from the communities used to get together at night to hang out, and now they can’t. They’re sent home as if there were a curfew. But the street is their home, the jungle is their home. And that’s a dynamic that has changed; ways of life are the first thing to change .”

The official discourse : "pseudo-environmentalists"

In his morning press conferences, the president of Mexico has referred to those organizing against the train project in Quintana Roo as “pseudo-environmentalists.” His criminalizing narrative that these individuals are paid “by the right wing” has been adopted and echoed by a large portion of his supporters.

“The official narrative of development to lift the southeast out of oblivion is very strong and convincing to working people. The message of ‘I’m going to lift you out of poverty’ is very powerful. They don’t want to believe they’re being lied to, because a large part of Mexico’s hope would crumble. On the other hand, the government has tried to deny that there are people who disagree, that not everyone is happy. When you go to these areas, you see everything people are doing to resist,” he points out.

Initially, environmental organizations opposing the Maya Train focused solely on protecting the ecosystem. There were—and still are—people who called for the train to be rerouted along the highway to save the jungle, but without questioning the project's overall logic. However, through the ongoing resistance, alongside other perspectives, another conceptual dimension emerged: it is more than just an environmental issue; it is about defending the land.

"At this point, we should realize that whether they put the train in the sky, in the air, or underground, the underlying problem is that it's a death project. It still infuriates me that some people are asking for the train to be put back on the road. We need to understand the geopolitical implications of this happening. People who don't live here, when we tell them what's going on, can't believe it. The level of decision-making is unbelievable. There's a climate crisis, the worst in centuries. And it's not like there's a lack of information about it."

The train that isn't going anywhere

Although one section has already been inaugurated, the megaproject has faced numerous obstacles due to resistance from communities, organizations, and the land itself. According to Morsán, " It sounds like magical realism, but the jungle is putting up a fierce fight . The reason they can't advance on section 6 is because of the number of caves. It floods constantly, or they encounter wetlands, getting covered in mud up to their knees. Several workers have told us they get lost in the jungle, sometimes for an entire day."

Some injunctions filed against the Maya Train are still active. They continue to explore avenues because the plan is to stop it. If it's proving so difficult, Morsán explains, it's because there are enormous interests at play that have been established for a long time. But that doesn't mean it can't be fought. She believes that self-criticism is needed within the Obradorista feminist movement on the Peninsula, along with a class consciousness that recognizes the impacts already being felt by populations with fewer resources to cope with the environmental crisis.

"The most important thing is not to believe the narrative that 'The train is going because it's going.' In reality, it's not going anywhere. It's going to a very bad chapter in the country's history."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.