Special report: the plot behind the fires in Los Alerces in Patagonia

Who benefits from the fires in Los Alerces National Park? This special report, in partnership with the Telúrica News Agency, reveals the key elements to understanding the situation, the accusations against the Mapuche-Tehuelche people, the real estate interests involved, and a historic struggle to defend their territory.

Share

This Special Report was produced in an investigative partnership between the teams of Telúrica, the Indigenous News Agency , and Presentes.

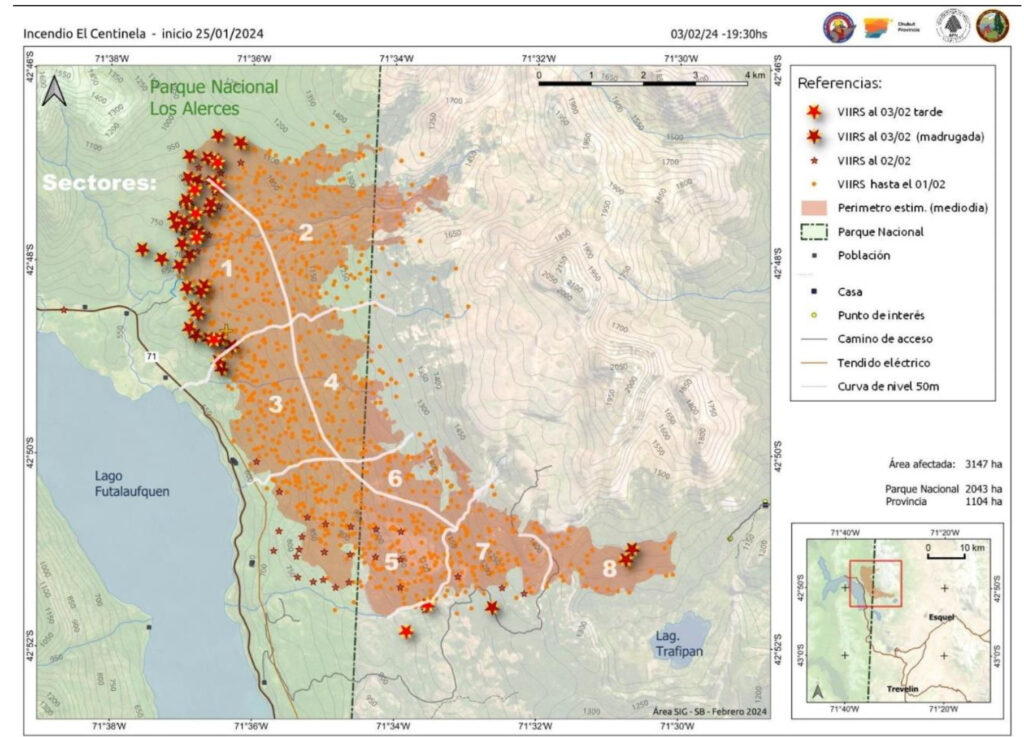

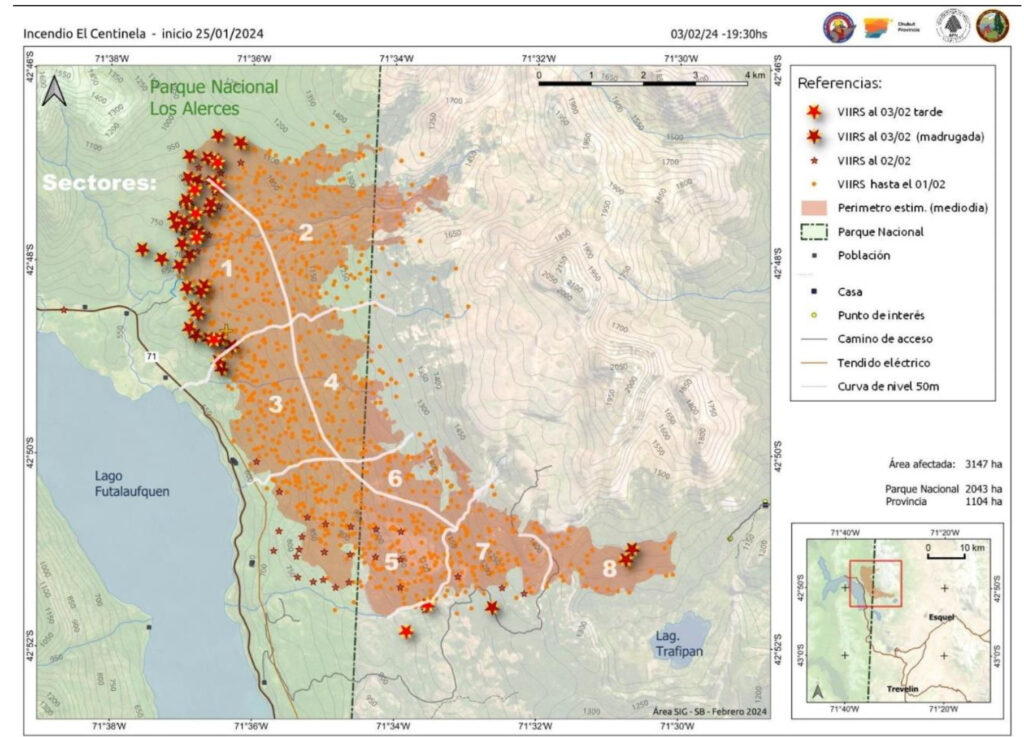

ESQUEL, Chubut. The city of Esquel has been shrouded in smoke for several days. A terrible sign: the forest fire raging in Los Alerces National Park, 35 kilometers from this city in Patagonia, remains out of control. Yesterday, gusts of wind fanned the flames, and four families had to evacuate their homes as a precaution. More than 3,500 hectares have already been burned, according to the latest statement from the unified command attempting to combat the blaze.

Fires are nothing new in this land of ancient trees and pristine lakes. Behind the flames and the public accusations leveled against the Mapuche-Tehuelche people who inhabit the area lie powerful economic interests and a multi-layered history—political, economic, judicial, and related to the fight against land destruction—that has unfolded over years.

How did the fire start?

The forests were already dry when the fire started. It hasn't rained in the area for a long time. On the other side of the Andes, Chile is also facing devastating wildfires, with more than one hundred human fatalities.

The fires in Los Alerces National Park began on Thursday, January 25th. They started in the area of the Centinela stream , near Lake Futalafquen, in what is now Los Alerces National Park (Chubut Province), Mapuche-Tehuelche territory. The fire then spread to other areas within the jurisdiction of Chubut Province. A unified command, comprised of national and provincial agencies and departments, has been fighting the blaze for the past 10 days.

“It started with two simultaneous fires, which suggests it was premeditated, to make it difficult to quickly control initially,” explained Danilo Hernández Otaño, superintendent of Los Alerces National Park, to the media, adding that they were intentionally set. According to his statements , “it was lit at nightfall, knowing that, according to safety protocols, firefighting must be done during the day.” The two fires merged and quickly spread out of control. Others say the fire started in the afternoon: “24 crucial hours were lost in fighting it,” says Moira Millán, a Mapuche weychafe (warrior).

A week later, experts from the Federal Police's Fire Investigation Division arrived to conduct their investigation. They are seeking to determine the origin of the fire, part of the federal investigation in which the Chubut government is a plaintiff.

A crime against nature

As it spreads, the fire devastates ancient native forests: ñire, lenga, coihue, and lahuan trees—that ancient South American tree that can live for over 4,000 years and gives the park its name—it's often called the Patagonian larch. It's estimated that these species will take between 120 and 250 years to recover and thrive. The Mapuche people speak of terricide and a crime against nature. They demand an investigation and that those responsible be punished under a new criminal category.

When the media asked the park ranger if he believed the origin could be in the area of the Paillako lof (see below) – knowing that Hernández Otaño has an unfriendly view of the Mapuche people – he replied: “There is no demonstrable and identifiable causal link, beyond the opinions one may have.”

What did the governor of Chubut say?

The Mapuche people speak of territorial reclamations. But the governor of Chubut, Ignacio Torres, when referring to the Paillako community, speaks of a “land grab.” Nor did the previous governor, Mariano Arcioni (2019-2023), recognize the pre-existence of the Mapuche Tehuelche people.

On Sunday, January 28, Governor Torres toured the fire zone and, before leaving, in statements to Radio Rivadavia amplified by Infobae, accused the RAM—an organization of highly dubious existence—and blamed the Mapuche people for the fire in Los Alerces National Park. He also hinted at what might happen: “There has to be an exemplary measure,” he stated, adding that “that park has to be evacuated as soon as possible.” He offered an explanation in line with the new government's policies, which, whenever possible, equate crimes with rights and transform those who protest or demand into enemies. “They are criminals who run a real estate business and do these things. So the problem isn't the Indigenous peoples, but these criminals who seize land under false pretenses. They do it in Neuquén, they do it in Río Negro, they do it in Chubut, and I think it's time to put a definitive stop to it,” said Torres, who has been a member of the PRO party since 2014 and headed the Pensar Foundation, the think tank of former President Macri.

The newspaper La Nación went further and accused, through an anonymous source, the weychafe Moira Millán of leading an organization considered terrorist: the RAM.

“The governor often makes these kinds of racist, right-wing statements. It doesn’t surprise me that he’s taking advantage of the situation, the fire in the park, where there are fires every year and then the land is appropriated,” says environmental and indigenous rights lawyer Gustavo Macayo, of the No to the Mine movement.

The story is well known to those who live in Esquel, Trevelin, or Corcovado, and they've seen how, over the years, more and more areas of the Park have been privatized. Now, they have to pay to access them. "It's hard to enjoy the Park, because the foreigners can afford it, but it gets more and more expensive for us," says Macayo. "Every year there are intentional fires. But then nothing is investigated. They call some scapegoat in to testify, and that's it."

The Mapuche people and a historic struggle

The Mapuche Tehuelche communities in the area responded to these accusations, first with a statement released on Sunday . “We want to make it clear that the Mapuche people have a long history of struggle in defense of Ñuke Mapu (Mother Earth); the forests are an essential part of our itrofil mongen (our way of life), and we would never harm them ,” they stated. They also denounced Joseph Lewis, a magnate of the Tavistock Group, as one of the people interested in developing businesses in Los Alerces National Park.

The British businessman based in the Bahamas is the subject of multiple lawsuits in various countries, including the United States . In Argentina, he is accused of blocking access to Lago Escondido in the province of Río Negro and illegally occupying land on a 12,000-hectare property whose sale is being questioned due to irregularities. A friend of politicians like Mauricio Macri, judicial officials, and the Clarín Group , a scandal erupted last year when it became known that a visit to his mansion at Lago Escondido was attended by judges, Buenos Aires city officials, a former intelligence agent, and an operative from the Clarín Group . The meeting at the lavish estate, whose access to Lake Lewis he keeps illegally closed, took place a week after a violent eviction operation in which, according to rights organizations, the rights of Mapuche women and children were violated.

In the statement, the Mapuche Tehuelche communities referred to the announcement of a project by Lewis's group: “the construction of a hydroelectric dam, among other real estate interests that exist precisely in the area where the fire started.” They also questioned the governor's notion of “good and bad Mapuches” and emphasized: “The Mapuche-Tehuelche people do not burn the forests; they protect them and live in harmony with them.”

Who benefits from the fires?

On Wednesday, January 30, at a press conference held in Esquel with the participation of members of Lof Pillañ Mawiza, Lof Catriman Colihueque, Lof Nahuelpan, Lof Inan Kume Rupu, Pu Lof Resistencia Cushamen and Lof Emilio Prane, the communities mentioned that three days before the fires started, Governor Torres had met with investors from the United Arab Emirates.

“The governor is a destroyer of the land. While he accuses the Mapuche people, he allows large transnational corporations to destroy the aquifers. If he is going to take responsibility for fighting ecocide (a word Torres used), he has to overturn the agreements with these land-destroying transnational corporations,” said Mapuche weychafe Moira Millán at the conference. She added, “We are going to file a lawsuit against him for his accusations, for inciting racist violence. We will also sue the newspaper La Nación. Now it seems there are good and bad Mapuches. Does Mr. Ignacio Torres have a Mapuche-meter?”

Among the questions left hanging after the conference was another one posed by Millán: Who benefits from the fires? “It’s obvious that the Mapuche people don’t.” “We Indigenous peoples have no history of terrorism. Our history is one of protecting life and nature,” added Gloria Colihueque Catriman, from the Mapuche-Tehuelche community Lof Catriman Colihueque, located near Lake Futalaufquen.

Other fires in Pu Lof, Mapuche territory

Forest fires in this territory of immense natural beauty in Patagonia have very recent and recurring precedents.

– In March 2022, another fire broke out in Los Alerces National Park, in the Laguna Larga area, near the Lof Catriman Colihueque , which ravaged 1,500 hectares . In that context, Mapuche brothers and sisters (pu lamngen) went to show their solidarity and brought tools to create firebreaks. At that moment, the Chubut police intercepted two sisters (lamgen) on the way up the mountain toward the territory. According to their later accounts, the police harassed them, filmed them, and then spread content on social media that defamed them and blamed another member of the Mapuche community for the fire. Faced with this institutional and racist violence, the two sisters—accompanied by other sisters, siblings , and supporters—filed a complaint with the prosecutor's office. But once again, the justice system ignored their complaint, and nothing came of it.

Recently, in December 2023 a column of smoke was spotted in the Lof Paillako community members of the community who came to help. In this same community, a few months prior, witnesses recorded the clearing of native forest by National Parks employees without the prior and informed consultation required by ILO Convention 169. The Lof Paillako community documented and shared this situation to highlight how National Parks provokes and intimidates the reclaimed territory and its inhabitants.

-Last summer, the Lof Paillako suffered at least three fires that affected one hectare of forest, a beehive and a broom thicket.

“Homes have also been set on fire on other occasions. In 2015, a house burned down in Costa de Ñorquinco, in a Mapuche community embroiled in conflict. In 2017, a house burned down in another Mapuche community near Leleque. Also in Alto Chubut, two elderly people died in a confusing fire,” shared anthropologist Hernán Schiaffini. He also recounted that in Esquel, in 2018, a confectionery shop burned down at the La Hoya ski resort (and the mountain was later privatized). In this case, arson was proven, but the perpetrators went unpunished.

Further investigations into the fires

“These fires are less publicized and smaller in scale, but they indicate that there are often vested interests at play. Or that fire can be a means to achieve a particular end,” said Schiaffini, who agrees with the phrase “All fire is political.”

However, he warned that in Los Alerces National Park, “it is unclear what interests are at stake through the fires.” He stressed the need to “deepen the investigations into this dimension of the fires: what do they express? Land disputes? Local or global? Transnational businesses? Which ones? Are they set to displace residents? Why? What tensions lie behind the fires?”

“Can anyone in their right mind believe that the Mapuche would set fire to the place where they live and where their ancestors lived?” asks the Lawyers' Association. This organization is representing the Paillako community in a case of “usurpation,” which “has been sent to trial” and for which “a start date is expected to be set,” they explained.

“The fires in the south have many causes: sometimes they are related to tourism that disregards the care of nature. Added to this is the lack of infrastructure to be able to extinguish them. Sometimes they are started by the companies themselves to take over the land for their economic purposes. But what cannot be doubted is that it is never the indigenous peoples who cause them; on the contrary, they are the ones who suffer them, because the defense of nature is ingrained in their very being ,” they emphasized.

Interests in the territory

Energy projects act as a magnet for the multi-million dollar investments that are being sought in the province of Chubut.

One of the projects that has been generating interest and concern in the region for at least five years is the IIRSA plan. IIRSA stands for Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America, a megaproject with many fronts in different territories of Latin America. In the Lago Puelo area of Chubut province, it aims to build an international border crossing.

It emerged in 2000 as an agreement between twelve South American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, and Venezuela), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the Financial Fund of the River Plate Basin (FONPLATA), and the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF). Behind the idea of “Integration and Development Axes (IDAs)” across the continent—according to IIRSA's own website—are “multinational strips of territory where natural areas, human settlements, productive zones, and trade flows are concentrated.” Researchers believe that, in practice, “each of these strips would be modified to interconnect extractive territories and configure trade corridors with outlets on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts: these have been called Bioceanic Corridors.” In other words, it is the construction of large infrastructure to connect production centers with consumption centers, making transfers cheaper and faster, further facilitating the exploitation of hydrocarbon deposits, minerals, energy, aquatic, agricultural resources and their transport, and at the same time reinforcing social control,” as explained in the publication Contra-IIRSA .

What do the fires have to do with the Omnibus Law?

In addition to the proposed repeal of the Land Law and the Mining laws included in Milei's DNU, the Omnibus Bill, which is still being debated in Congress, also includes modifications to the Forest Law , the Glacier Law , and the Fire Management Law .

The situation is alarming to locals, and not just Indigenous communities. The proposed new Article 517 in the Omnibus Law seeks to legalize the sale and change of land use in burned areas by repealing Law 27.604 on fire management, enacted in 2020. This law is crucial for preventing intentional fires for real estate speculation, as it prohibits the use and sale of land after a forest fire. This amendment could lead to intentional fires in areas of real estate interest, as has already occurred. This situation fundamentally affects the pre-existing communities that safeguard life in these territories.

“The lands ravaged by fires, which happen every year, are then appropriated by people who want to do business. And even more so now that the Forestry Law is at risk of being repealed. It's a very big risk. National parks are a money-grabbing machine, and they're going to take advantage of it, but there are no serious preservation policies,” says Macayo.

"Only Argentine flags"

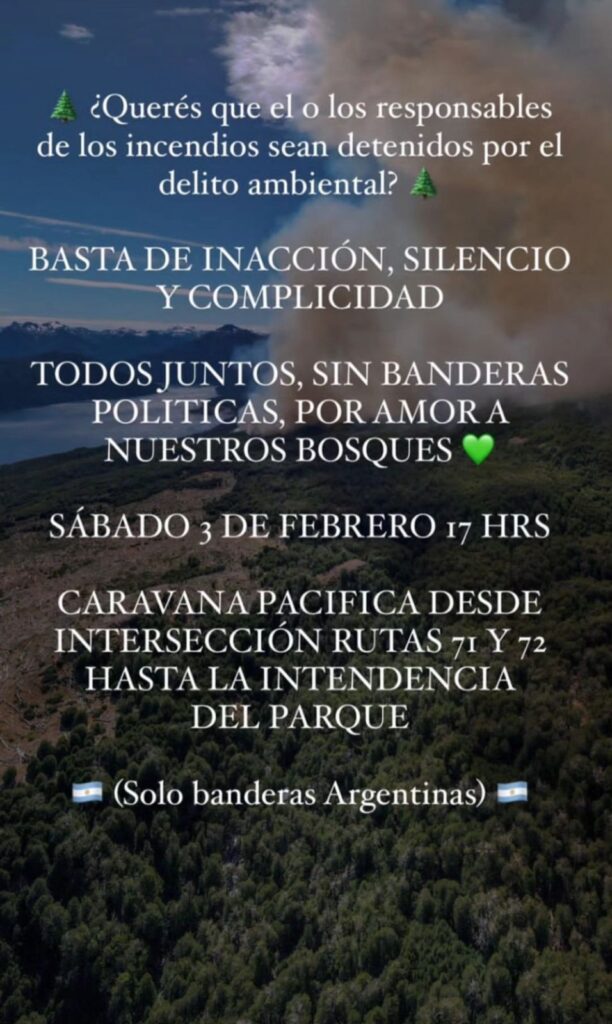

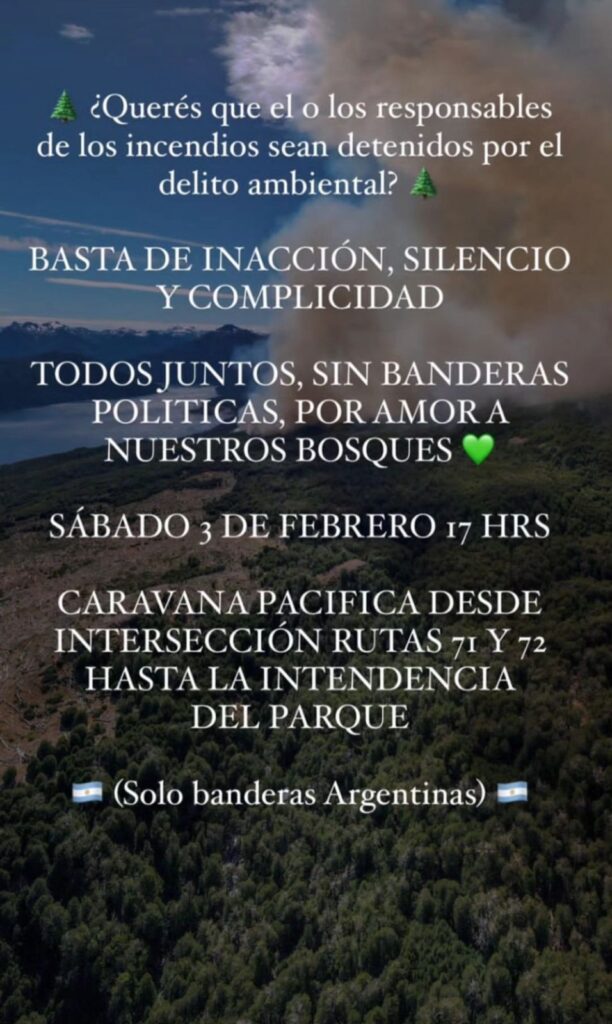

In this context, the call for a caravan in Esquel drew attention: “Do you want those responsible for the fires arrested for environmental crimes? Enough of inaction, silence, and complicity.” It was on Saturday, February 3, and the flyer warned, “Only Argentine flags.”

Members of Agencia Telúrica explain: “We believe this is not an innocent clarification, since Mapuche Tehuelche flags have always been present in contexts of struggle. Thus, this “peaceful” gathering (as they call it) also contributes to this racist violence against the Mapuche Tehuelche people.”

Behind the call to action are members of the Rural Society and many anti-Mapuche individuals. "Although it also includes those who are asleep, still unaware of this manipulation that makes them believe that an ancient people, predating the Argentine state, is capable of threatening its own existence."

More than 150 indigenous communities in Chubut

“The governor’s reaction, pointing to the Mapuche people as the perpetrators, whether directly or indirectly, was not only ill-advised, insulting, and slanderous, but also an attempt to create an internal enemy. Furthermore, it evades other matters that must be addressed in court,” says Sonia Ivanoff, a lawyer with AADI (Association of Indigenous Law Attorneys of Argentina). She is referring to two court rulings. “The governor of the province of Chubut has been ordered to guarantee the right to consultation and participation of Indigenous communities. There are more than 150 Mapuche communities throughout the province,” she notes. “The governor prefers to ignore the order rather than regularize this issue. For years, Chubut has been negligent in its handling of public land. He must guarantee Indigenous communal land ownership. And, on the other hand, he must recognize bilingual intercultural education within the provincial government.”

Ivanoff also points out that Torres “is appointing people of Mapuche origin or with Mapuche surnames to political positions where the communities have already told him not to appoint anyone. There are no representatives elected by the communities in the Chubut government, and yet he continues to refuse to comply with court decisions.”

RAM: An invention of the intelligence services?

There is no verifiable evidence of the existence of the RAM (Resistencia Ancestral Mapuche) in Argentina. And generally, those who mention it are all from the PRO party (Patricia Bullrich, Governor Torres) or anonymous sources cited by the media.

“Nobody knows where it operates or what kind of organization it is,” explains Gustavo Macayo. He recalls that in Argentina, nobody had heard of it until around 2015, when Jones Huala, who had previously been in Temuco, Chile, became known for the Lof Cushamen en Resistencia (Resistance Movement), which claims territory held by Luciano Benetton. “The RAM (Resistencia Ancestral Mapuche) was constructed as an internal enemy during Macri's time to create an Indigenous enemy; it suits the State because it treats them like terrorists. This was done using the State's intelligence services to investigate this land occupation,” says Macayo. There is currently an open case for espionage by the AFI (Federal Intelligence Agency). The media hardly mentions it.

In contrast, “Jones Huala’s case is closed and he’s detained there. But whenever something happens, they blame the RAM or the Mapuche,” says Macayo. He asserts that in the Comarca region—Esquel, Trevelin, Corcovado, Cholila, Puelo—many people were subjected to illegal intelligence gathering by the AFI (Federal Intelligence Agency). Both he and Moira Millán were among those spied on in 2015. The case is going to trial this year.

Several sources claim that the RAM (Resistencia Ancestral Mapuche) is a fabrication of the intelligence services to justify the criminalization of the Mapuche people. In the words of Claudia Ermili, a member of the APDH (Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos) in Esquel: “The RAM is constantly accused of anything and everything. We're very used to them throwing around accusations that the RAM is responsible for this or that, and the truth is, it's never proven, it never has been.”

The anti-Mapuche statements made by officials, such as Governor Torres in this case, are neither new nor unique, Ermili points out. “We already experienced this with other governors, like the late Governor Das Neves, where someone from the Mapuche community was always singled out as the bad guy, the one who does harm.”

“Through this creation of the figure of the internal enemy, the demonization is deepened to justify the militarization of territories, considering this ancestral people as a group of terrorists. The one acting as terrorist is the State; through it, the various governments in power exercise violence, dispossession, and death. Under this representation of the Mapuche people, the murders of Santiago Maldonado and Rafael Nahuel in 2017 were justified,” expressed voices of the Mapuche Tehuelche people who live in the area.

During those years, Patricia Bullrich produced a 180-page report called "Revaluation of the Law. Problems in Mapuche Territory," accusing members of the Mapuche people, social organizations, and media outlets that had shown solidarity at that time of institutional violence in Chubut and Río Negro with impunity.

“This report, based on disinformation, is sowing hatred and creating a scenario of terrorism to blame the Mapuche people. Based on false information, part of the population justifies the deployments of special security forces. This fabrication is part of a strategy to prosecute, imprison, and weaken the Mapuche people, who defend life in their territories. Meanwhile, these politicians are negotiating away these territories with corporations. They are threatening the lives of the rivers, forests, animals, and people who inhabit them,” the same sources said.

The configuration of the external enemy for the installation and intrusion of US forces into the territory, which they intend to install in Patagonia and against which the Mapuche people have been fighting.

The prosecutor's office investigating the fires

The day after his visit to Los Alerces National Park, the governor met with Guido Otranto , the only federal prosecutor in Esquel. Otranto was heavily criticized when he was in charge of the case of Santiago Maldonado's disappearance in 2016, amidst an operation orchestrated by Bullrich under the Macri administration.

The governor told reporters, “We have decided to file a lawsuit to closely monitor this case, to ensure the expert analyses are carried out as soon as possible, and to demand an exemplary measure. This doesn't have to be simply suggesting that the Park improve its infrastructure, which we agree with, but there has to be someone responsible, and they have to be imprisoned.” He also urged the Justice system to act swiftly in the case of the land occupation, adding, “The residents of the National Park cannot be left in suspense, living in fear of having their homes burned down, with a squatter inside the Park.”

In September 2017, Judge Otranto ordered a violent raid on the Vuelta del Río community in search of Santiago Maldonado. He ordered this massive operation in the early morning hours, deploying 400 officers, dogs, a helicopter, and approximately 30 vehicles. At that time, several communities gathered at the Federal Courthouse in Esquel, peacefully occupying it to demand the judge's resignation, the removal of the officers involved, and an investigation into this abuse of power, during which community members were imprisoned with zip ties and left lying on the floor for hours in the middle of the night, their rukas (traditional houses) were set on fire, and other irregularities were committed. But their demands were ignored.

Precarious brigadistas

There are around 300 firefighters, with the collaboration of municipal, provincial, and national institutions, trying to extinguish the fire amidst ash, smoke, and wind, and in a context of complaints and protests over precarious working conditions . This adds another dimension to the ongoing conflict over wage negotiations, a demand the firefighters, who are provincial government employees, have been making for some time.

On January 18, firefighters from the Provincial Fire Management Service protested in Esquel, in front of the Forestry Secretariat. In his statements, the governor did not mention, nor did most of the media, the conditions under which they are fighting the fires.

According to Ivanoff: “Today, public health doctors and nurses are assisting these firefighters; many are purely volunteers and driven by their dedication. They are working under precarious conditions. Some people have been doing this kind of work for 20 years. And for the past 20 years, the mismanagement of public land, corruption, and fires—in a province that once had a native forest and protected areas—have led to ever-increasing deforestation. Various voices have been heard, not only from the Mapuche people, but also from other sectors and organizations, criticizing the fragility with which the ruling class protects these common resources.”

“The firefighters, especially those in the provinces, are in dire straits, neglected, and facing wage problems,” says Macayo. For him, a crucial part of the problem is the lack of year-round prevention and investment policies.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.