The first transmasculine memory archive in Mexico is created

The manager of the archive, which is currently virtual, explains how this idea came about. "Memory is not just recollection, it is also the present," he states.

Share

MEXICO CITY, Mexico. “There is a lack of knowledge about our histories,” says Aldri Covarrubias, manager of the Transmasculine Memory Archive MX . Presentes spoke with Aldri about building an archive focused on transmasculine people in Mexico, the importance of carefully collecting their narratives, and how this, in turn, fosters a form of care and connection among people who “live, whether by choice, temporarily, or permanently, in non-hegemonic masculinity,” as Covarrubias explains.

The Transmasculine Memory Archive MX , currently hosted online with some in-person activities in Mexico City, is inspired by the Trans Memory Archive of Argentina Trans and Escapes project , a Mexican archive run by Laura Glover, who writes chronicles to recover the stories of trans women and their survival , their experiences on the streets, and their struggles with crime.

“The Transmasculine Memory Archive is a space aimed at producing its own forms of knowledge based on the experience of transmasculinities in Mexico. That is, all these non-hegemonic masculinities in terms of gender. Including non-binary people, race, and even other aspects that have been constructed in the past, and still in the present, such as truck drivers, butch women, and male transvestites,” Aldri explains.

The Mexican transmasculine memory archive not only seeks to trace the past through efforts to search for and verify historical information from various sources such as journalism, historical archives and film, but also to build memory from embodied experiences recounted in life by transmasculine people , the encounters and the recovery of art about transmasculinity produced by transmasculine people.

From a location on the eastern outskirts of Mexico City, Aldri Covarrubias answers five questions for Presentes.

–How is this memory archive built?

-It's primarily about trying to trace the lived experiences of transmasculine people. It's not just about compiling information from journalistic or purely historiographical efforts of the past. This is a methodological decision because there are gaps in our understanding of our experiences; there's no record, no database. There's nothing where our experiences are systematized. There's a lack of knowledge about our histories , and deciding not to consider a strictly chronological or historical narrative is a starting point from which we can situate knowledge of our lived experiences.

This archive is not a catalog of transmasculinities. The aim is to see how transmasculinity influences and has influenced public life because we, we, think of transmasculinity not only as a gender identity but also as a way of seeing the world. I don't stop being trans when I take off my clothes. I am trans all the time, and my gender transition is not the only thing that affects me; there are many coordinates from which we can express ourselves.

–What triggered the need to construct a transmasculine memory?

-A very marked weariness in my personal life because I kept telling myself I can't be the only one . And the urgency to be able to look back and to the present to say that we are here, that we can bring back from oblivion those stories that concern us.

Of course, it also has to do with my age. I'm in my 30s, so I ultimately went through a kind of grieving process knowing that it wasn't through biological reproduction, as a person who could bear children, how I was going to seek that transcendence, which I think is a very human desire. Our own mortality confronts us with that question, and in the end, I don't see it as a matter of legacy but of ancestry.

If we have all these figures we call "mother, " like Madonna or figures in ballroom dancing, which the LGBT movement has ultimately distorted from the traditional, cisgender, patriarchal family, then I've felt the urgency to ask: Where are the grandparents? Where are these others, these "others" who can inspire us? Mainly to know that we're not starting from scratch, to remind ourselves that we won't go silent. Above all, in this fascist affront we're experiencing in the world, this memory is also a proposal and a counterattack against it.

–It is common for trans memory to be linked to a narrative of death. How does this archive construct and create memory?

We don't want to build memory based on experiences that the person can no longer deny about what their life was like. This archive, in that sense, takes up what activism and mad pride say about first-person experiences. Nothing about us without us. And that breaks the logic of the film director, the psychiatrist who diagnoses us, the doctor who gives us hormones.

For me, this shift in perspective stems from looking back at the history of this entire collection of memorials, which was particularly relevant. Above all, the response to the HIV epidemic, with its logic of grief management and the construction of meaning, is something I think is very important for us to reclaim. Because these movements also offered the possibility of rethinking death, especially in the face of a fascist affront that seeks not only our death but also the elimination of our transcendence.

This archive recovers that, in that sense, that death is not destiny. So the commitment is to life. Because we, we too are lives unfolding , and what we choose to share about ourselves, we, is a powerful force in the face of extractivism and the logic of death that is so prevalent today against trans people.

-Why opt for building memory while alive and from the present?

-Leaving it solely as a search in the past is a double-edged sword. If what we want is to label, classify, and systematize transmasculinity, we would only have about 60 years of history where we could find some data. But these would almost certainly be represented as objects of medicine, sensationalist journalism, or gender studies.

The other side of the coin is that there is still unexplored territory to revisit. When we talk about transmasculinities, we encounter other major themes of the human experience, such as migration, the concept of health and illness, fatherhood, and so on . These are experiences we can examine critically, and it is there that we might also find these stories.

This formation of knowledge, between the past and embodied histories, told by them, could not happen without clarifying that traditionally the trans experience is permeated by extractivism, especially by the scrutinizing gaze of cis people, where we are seen as objects of study, documentary subjects, objects of spectacle. But never from any other perspective, such as producers, journalists, or historians.

For me, it's important to revisit stories while we're still alive because memory isn't just about the past, it's not just about remembering, it's also about the present. I believe that remembering from the present also means seeing ourselves as active participants, so we can no longer remain complacent, thinking, "I did what I could, and it'll be up to the younger generation to keep the ball rolling ." Why? Remembering while we're still alive is also, in a way, confronting everything that seeks to erase us. So, while we're still alive, these are our times.

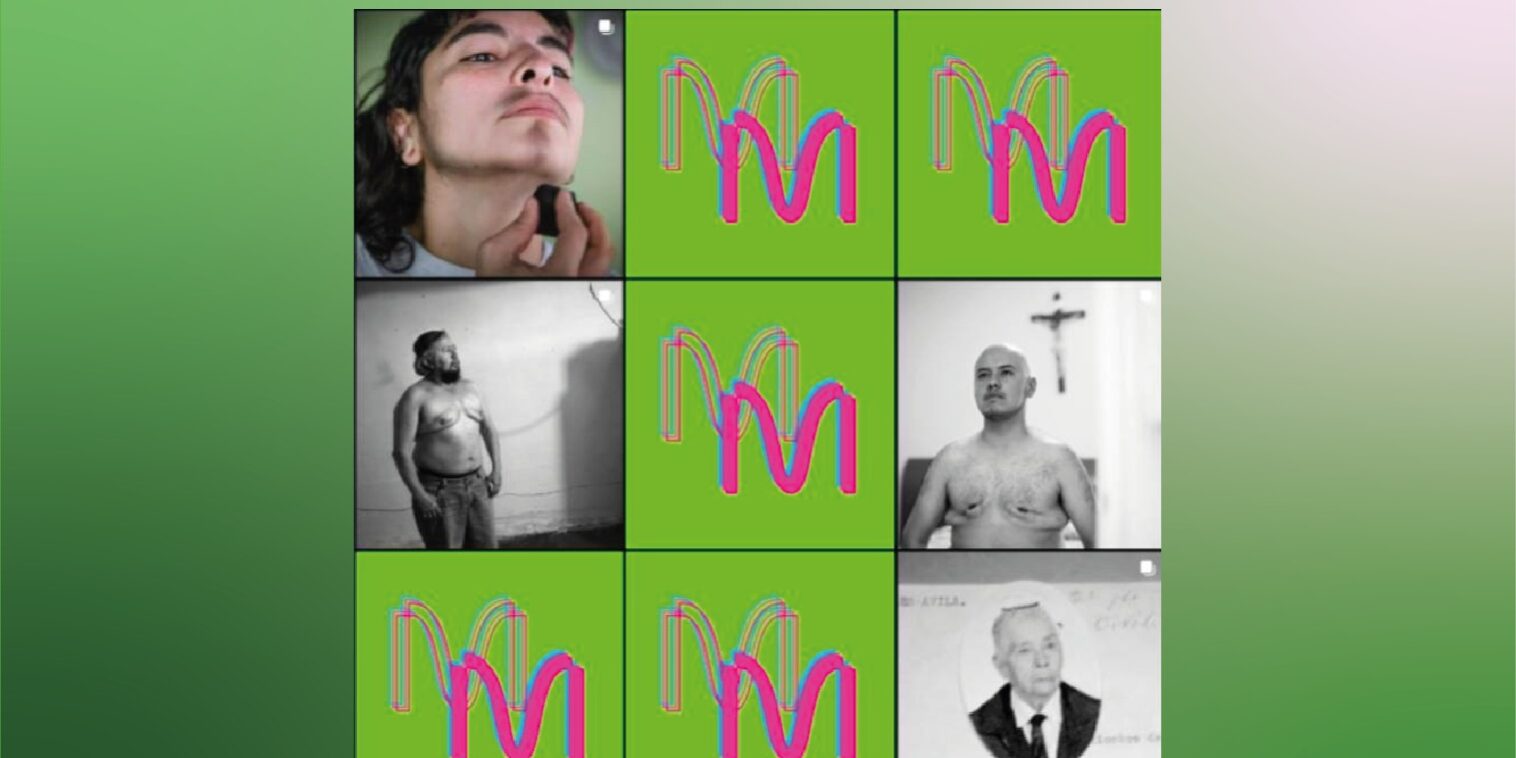

Photo: Geo González

-What is the value of creating physical meeting spaces like the Memorial Social Club that emerged from this archive?

-It's primarily a response to the lack of role models, representation, and opportunities for transmasculine people to connect. The initial idea behind creating the Memorial Social Club stemmed from the fact that there are people just beginning to explore their non-hegemonic masculinity, and there's a need for a space to do so without judgment or prejudice. Because with the rise of identity politics, masculinity is now being simplified and equated with man = oppressor, male = violent.

Photo: Geo González

So, beyond seeking acceptance in other LGBT spaces, it was important for me to try and rehearse what one would look like that put transmasculinities at the center. Not because we want to be a boys' club, but to build community. And board games were the perfect option because, upon recognizing my own social awkwardness and that of some of my peers, I thought that board games allow for this kind of forced socialization. It was an exercise that allowed us to listen to each other, to connect, to talk amongst ourselves, for more than 20 hours in three different sessions.

***

If you want to participate in the archive with your story, you can send a message to the Instagram account of Archivo de la Memoria Transmasculina MX.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.