The invisible (trans)feminicides in Puebla

Although the murders of trans women in Puebla exhibit characteristics of femicide, the authorities do not investigate them as such. Nor do they investigate them as hate crimes, thus rendering these crimes invisible and leaving them unpunished in the state.

Share

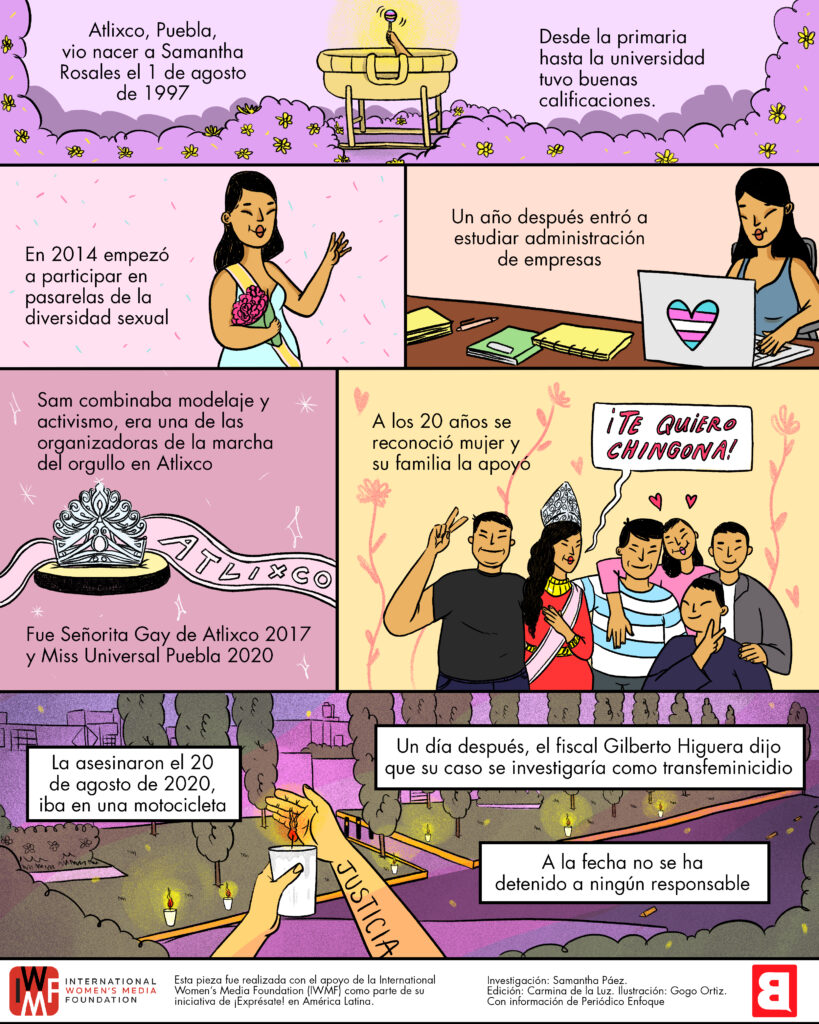

PUEBLA, Mexico. In the early morning hours of August 20, 2020, a police officer knocked on the door of Samantha Flores Rosales's house to tell her family that she had been in an accident on Ferrocarriles Avenue in Atlixco, Puebla. What the officer didn't say was that Sam, as she was affectionately known, was dead: a car had chased her, knocked her off the motorcycle she was riding, and then run over her body. Her mother, Fabiola, learned that Sam's death was not accidental, but rather a case of trans femicide, after people told her about a video showing the last moments of her daughter's life.

A transfemicide is the murder of trans women committed out of contempt for their identity or a sense of ownership over them, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . Sam's is one of 33 that have occurred in the state of Puebla over the past 11 years. These are recurring stories: violent murders, addressed by authorities and the media as crimes of passion, fights, or robberies.

A day after Sam's murder, Puebla's Attorney General, Gilberto Higuera Bernal, acknowledged that there were grounds to consider it a femicide . However, the agency later revealed, in response to a freedom of information request, that no murder of a trans woman is investigated as such.

For the murder of a trans woman to be considered a femicide, according to the Prosecutor's Office itself, it is required: "that the person in question is identified as a trans woman in accordance with the laws applicable to the matter, and that the crime in question was carried out in accordance with Chapter Fifteen of the Penal Code of the Free and Sovereign State of Puebla."

This would mean that only if the murdered trans women had changed their self-perceived gender identity would the crime be investigated under the femicide protocol, even though these are murders carried out with cruelty, cruel treatment, torture, in which there is usually an affective or trust relationship with the perpetrator, exposure of the bodies in public space and previous violence, causes of the crime of femicide, classified in Puebla since 2013.

Meanwhile, transfemicides seem invisible to the authorities.

The beginning of a struggle

On Wednesday, March 7, 2012, Brahim Zamora last saw Agnes Torres Hernández, his friend and collaborator on sexuality projects. She told him she was going to Chipilo, in the municipality of San Gregorio Atzompa, that weekend. She let him know so he wouldn't worry, since she had previously given her friends a scare by going out partying and not contacting them for a long time.

That's how Agnes was, says Brahim, she lived intensely.

Two days later, she was murdered and her body was found in a ravine near Atlixco. The crime was committed by people she knew . The brutality was evident, but at that time, hate crimes and femicides were not classified as separate offenses from homicide in the Puebla Penal Code.

As soon as news of Agnes's murder spread, dozens, if not hundreds, of people gathered in the main square of Puebla. The plaza was filled with white candles, images of Agnes's face printed in rainbow colors, heartbroken hugs and tears, but also with profound outrage.

From that moment on, there was a strong demand that crimes against members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex (LGBTI+) community be investigated as hate crimes.

They requested the creation of a State Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination , a Gender Identity Law, a specialized unit to investigate the murders of women and people of sexual diversity, and the designation of May 17 as the State Day Against Homophobia.

Some of the demands took almost ten years to be met, others were only partially fulfilled.

The classification of hate crimes occurred in July 2012 ; the state law against discrimination was issued in November 2013, but so far the council that analyzes acts of discrimination has not been installed; the designation of the Day against Homophobia was made in May 2019; the specialized unit was created in November 2020 , and the Law of Self-Perceived Gender Identity in Puebla , also known as the Agnes Law because the activist was the first to promote it, was approved in March 2021.

Despite the fight for the recognition of hate crimes, the initiative has not yielded the expected results. According to information provided through a transparency request by the Puebla Attorney General's Office, from January 2013 to August 2023 there were 14 hate crimes against men based on gender, which could be trans femicides.

Official figures acknowledge three cases during 2013; four in 2014; six in 2015; and one in 2016. There would be zero cases in the years 2017 to 2023.

Regarding hate crimes based on sexual orientation, the Prosecutor's Office provided the exact same data: 14 murders of "men" between 2013 and 2016. That is to say, from 2017 to date there are no officially recognized hate crimes motivated by transphobia or homophobia in Puebla.

In contrast to official figures, this investigation compiled a historical record using databases of possible transfeminicides collected by Letra S and Vida Plena, both civil organizations, in addition to conducting its own press review.

This review reveals that 33 probable transfemicides occurred between 2012 and 2023, 135% more than those reported by the Prosecutor's Office. Of these violent murders of trans women in Puebla, at least 15 happened from 2017 to the present.

The places with the most cases are: Puebla , Atlixco and Tehuacán.

A violent place

It is no coincidence that the city Agnes fled from, despite having been born there and having enjoyed a happy childhood, is Tehuacán, where she received threats and was the victim of an attempted attack.

According to the aforementioned newspaper review, at least five transfeminicides occurred in that municipality from January 2012 to November 2023. Kevin Williams, spokesperson for the Union of LGBTI+ Collectives of Tehuacán, says that they have counted 15 hate crimes from 2010 to 2020, some of them extremely violent.

During an interview, Kevin recalls one in particular.

—When they call you at four in the morning and tell you: William, your best friend has just been killed , it's not easy and you never get used to it, it never stops hurting and you never forget the faces.

This refers to the murder of Bárbara Lezama, which occurred on April 30, 2011, in the city of Puebla. Bárbara, tall, charming, and beautiful, had gone out to a nightclub with a friend in the Zavaleta area ; hours later, she was brutally murdered.

In a very similar way, three other crimes against trans women occurred in Tehuacán: Regina Echeverría, in 2013; an unidentified woman, in 2016; and Yadira, the manager of a bar, in 2017. Others, such as Charly and an unidentified woman, were found dead with signs of torture and infamous injuries.

As in Sam's case, the characteristics of these murders fit some of the causes of the current criminal type of femicide in Puebla .

In fact, in the historical compilation of 42 violent murders of trans women from 1996 to November 2023, in 39 there is sufficient information (causal) to consider them femicides.

Of all the historical cases, 25 involved infamous or degrading injuries, sexual violence, or cruel or inhuman treatment; in 22 cases the body was displayed in public; in 11 there were indications of a sentimental, affective, or trusting relationship with the perpetrator, and in two cases there was a history of violence, threats, harassment, or previous injuries.

In Tehuacán, violence against trans women and people of sexual diversity is a constant, although it does not always culminate in murder.

Kevin Williams recounted that in July 2020, a trans woman known as Jeidy was chased and shot by mechanics. Her case is one of the few where the perpetrators have been convicted . In 2022, around the time of the LGBTI+ Pride March, a Telegram group was discovered in which several people were organizing to kill gay men .

—This attempted attack was so strong that even the governor (Luis Miguel Barbosa Huerta) got involved—recalls Williams, who was outside the event that took place after the march, in a nightclub, checking each of the people who entered, and private security was also hired to prevent the threats from being carried out.

While acknowledging that this threat was against the LGBTI+ community in general, the attacks against trans women in the municipality are more pronounced, as they are subject to domestic violence and discrimination in public spaces.

"What is most visible is what is most attacked," says the activist.

According to the report “ The Traces of Violence Due to Prejudice: Lethal and Non-Lethal Violence Against LGBT+ People in Mexico ”, prepared by Letra S, 55.2% of hate crimes against sex-diverse people, from 2018 to 2022, correspond to trans women.

Figures from Letra S place Puebla 11th nationally in terms of transfemicides. However, they only count 11 cases from 2015 to 2022, while the newspaper review conducted for this study identified a total of 21 cases during the same period.

The discrepancy in the data stems from the source used: the media. Ana Laura Gamboa Muñoz, from the Observatory of Social and Gender Violence (OVSG) at the Ibero-American University of Puebla, maintains that throughout Latin America there is a deficiency in the recording of these murders. Consequently, many civil organizations compile their own records, which can lead to complications that would need to be addressed by an official registry, in this case, managed by the Attorney General's Office of the state of Puebla.

Atlixco and impunity

An example of how transfeminicides go unnoticed by both the media and the authorities is the case of Yoksana or Pamelitha Martínez Vázquez, a 22-year-old woman murdered in Atlixco, whose body was left in the middle of the city's main square in 2015.

It wasn't until 2020, when Samantha Flores Rosales was murdered, that a mutual friend confirmed Yoksana was the first trans beauty queen killed in the municipality. He didn't provide further details, but a review of social media revealed that she was originally from Mexicali, Baja California, had arrived in Puebla around 2012, and while the exact date of her death is unclear, one of her sisters posted a photo of her with the caption "I miss you" on October 1, 2015.

Atlixco, known for being a Pueblo Mágico (Magical Town), for its flower sales and its warm climate, is second in the state for transfeminicides, with six cases from 2012 to date, according to the newspaper review.

The transfemicide of Samantha is perhaps the most widely reported, not only because of the viral video of her murder, but also because she was an activist in the LGBTQ+ community in Atlixco, collaborating with the organization of the Pride march in the municipality. She had also been recognized as Miss Gay in 2017 and Miss Universal Puebla in 2020.

Her mother, Fabiola Rosales, maintains that what distinguished her daughter was not only her being an excellent student, but also her big heart; she was always willing to listen to people and offer advice. Even now, three years after her murder, wherever she goes she encounters people who knew her daughter and remember her fondly.

—More than a mother, she was also like a friend; anything, any problem, she would always talk to me. I would talk to her too […] Her way of being was always to give advice, support, both to me and to several of her friends.

Samantha, originally from La Magdalena Axocopan, a community where urban properties are interspersed with fields of flowers, was always accepted by her parents, siblings, and grandparents. Her goal was to write a book about her transition process. That and other plans were cut short when a car deliberately ran her over, and the driver of the motorcycle Samantha was riding fled the scene without seeking help.

Danna, a friend of Sam's, said that the week before her murder they had planned a trip to Zacatlán, in the Sierra Norte region of Puebla. It was very hard for her to learn that Sam's life had been taken, not only because she lost a confidante, but especially because she believes the attack was premeditated.

"It affects me a lot because we've fought, I think in this entire trans community we've fought so hard to be respected as such. And yes, I do think it affects me a lot that sometimes justice isn't served for some people, because we are all equal."

So far, the murder is not being investigated under the femicide protocol, and no one has been held responsible. Ms. Fabiola stated that they did locate the driver of the motorcycle her daughter was riding and even had a confrontation with him, but neither he nor anyone else has been arrested.

—In Atlixco, the authorities were terrible, because there were cameras where supposedly no one had access, there were cameras that weren't working, they were broken, supposedly. Then the Puebla Prosecutor's Office for femicides said: we couldn't do our job as we would have liked because Atlixco, frankly, didn't give us the opportunity to work.

Cinayini Carrasco Colotla, director of the Citizen Observatory of Sexual and Reproductive Rights (Odesyr) and member of the Atlixco Feminist Network, said during an interview that the lack of data on violence against women, in general and trans women, in particular, is a problem in the municipality.

—Do you know what the problem is there? That there really is no information, suddenly nothing is said, suddenly it comes out as a news story, obviously there is violence, but it's like: man dressed as a woman was murdered.

Although the Atlixco city council has the obligation to make a diagnosis on violence against women, as mentioned in measure II of the declaration of gender violence , the document has not been updated in this municipal administration and the existing one does not include trans women.

—It seems as if they are made invisible—Carrasco Colotla asserted.

Invisible femicides

As in the cases of Agnes, Yoksana, and Samantha, most of the trans women murdered in Puebla were left in public spaces, a common trend also seen in the case of cis women .

According to the historical data, of the 42 violent murders of transgender women since 1996, 25 of the bodies were found abandoned in public places, ravines, bodies of water, vehicles, or public squares. Seventeen of the bodies were found in homes, hotels, or businesses, considered private spaces.

Another finding from the analysis is that in 16 cases the legal name or assumed name of the trans women is unknown, meaning there is no information about their identity or their history.

Gabriela Chumacero Rodríguez, president of the Trans Group in Puebla, commented that many of the victims, who are unidentified, are sex workers, some of them Central American migrants, indigenous people, or poor people who do not have papers to prove their identity.

Regarding the occupation of the trans women who were violently murdered, the most common are: sex worker, with ten cases; employee, with four; merchant, also with four cases; and activist, with three cases.

For Gaby, the job, then, is to negotiate with the authorities to get the bodies released and give them a dignified farewell, since their families rarely claim the remains and they are usually taken to the mass grave.

—We as activists say: we may not be family, but she's my sister, because we live together. She's from Honduras or El Salvador, from Veracruz, from Tehuacán, or wherever you want, where her family discriminated against her, kicked her out of her home, and she never came back [...]. So it's true that discrimination starts at home.

According to the 2022 National Survey on Discrimination (Enadis) , prepared by the National Institute of Geography and Statistics (Inegi), 61.6% of the people surveyed believe that trans people (transgender, transsexual or transvestite) are respected little or not at all.

Ana Laura Gamboa, from Ibero Puebla, believes that in the case of trans women there is a social or symbolic construction of gender, a feminization of their bodies that places them in a more vulnerable condition than other sexual orientations and identities.

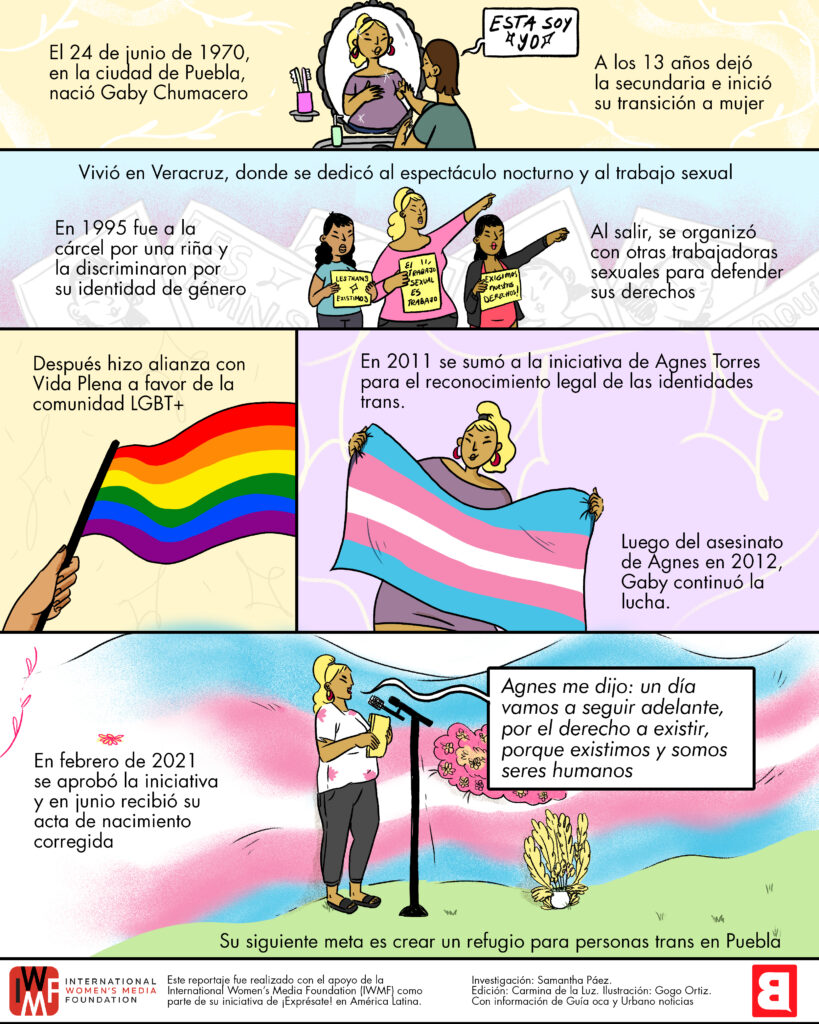

Gaby Chumacero knows what it's like to face discrimination for being a trans woman. At 14, she dropped out of school and began her transition to female, with the support of her mother and the rest of her family. She ventured into variety shows and sex work.

One night in 1995, she was involved in a bar fight and was arrested. From that moment on, and during her stay at the San Miguel Social Reintegration Center (Cereso) in Puebla, she was subjected to abuse, such as being forced to remove her clothes and expose her genitals, having her hair cut, being forced to wear men's clothing, and being beaten and mocked.

When she was released from prison, Gaby began organizing with other sex workers to defend themselves, but also to train in various trades at the suggestion of activist Alejandra Fonseca. Gaby graduated as a colorist. A few years later, she met the organization Vida Plena, where she began her work on behalf of the LGBTI+ community. She took a workshop with Agnes Torres, and they became allies in promoting the recognition of transgender identity.

—There was no friendship, or anything, it was just: hi, how are you. I went to one of her workshops, she told me: one day we're going to move forward, for the right to exist, because we exist and we are human beings.

With the murder of Agnes, Gaby not only focused on promoting the identity law, but she has also sought to include transfeminicides in the Penal Code of Puebla.

—These crimes are simply dismissed as settling of scores or crimes of passion; that's how most of them will be recorded by the State Prosecutor's Office, because if they are treated as hate crimes, they have to be buried deep down, like with femicides against women [...]. Today, femicides and trans femicides—we want them to be classified as such, to be treated as such.

In this regard, experts believe that the authorities in Puebla should investigate all these homicides with a gender and sexual diversity perspective.

Jair Martínez Cruz, a professor of Gender Studies and member of Letra S, opined that the tools available to authorities to investigate these cases are not being used. This is despite the fact that 19 states have an aggravated homicide law based on hate, as is the case in Puebla.

For Jair Martínez, it is regrettable that the concept of hate crime is not being made operational, since the same thing happens as with femicide: they exist as autonomous criminal types, but the investigation teams do not use them.

From Martínez Cruz's perspective, a fundamental condition for understanding hate crimes is the brutality and cruelty with which they are committed, in addition to the severe bodily harm inflicted, as outlined in various investigation protocols. The problem is that this information is not known to all prosecutors.

In at least 12 historically documented transfeminicides there were signs of torture, and in three of them there was sexual violence.

Ana Laura Gamboa, head of the OVSG, said there are three ideal ways to investigate trans femicides: as femicides, as hate crimes, or by creating a specific criminal offense . Even so, the important thing is that these tools don't remain just on paper and that the Prosecutor's Office actually uses them.

—The legal classifications are extremely important, but not sufficient. Because we find ourselves in a scenario of impunity where due diligence or the ways in which, for example, in the case of femicides, gender-based reasons are proven, do not seem to be operational despite having protocols.

Onán Vásquez Chávez, a member of Vida Plena, focused on the Superior Court of Justice of Puebla, saying that although the concept of hate crimes is still under construction, for judges it is even more diffuse because they lack training in gender perspective and sexual diversity.

An example of the lack of a diversity perspective is that the Court does not have disaggregated data on homicides qualified by hate due to gender or sexual orientation, as stated in its response via transparency.

While justice authorities neglect their responsibility to investigate and prosecute transfemicides, these crimes continue to occur. On November 12, 2023, 21-year-old Melani was murdered in her home just meters from the Specialized Investigation Unit for Domestic Violence and Gender Crimes in downtown Puebla.

The fight continues.

* This report was produced with the support of the International Women's Media Foundation (IWMF) as part of its Express Yourself! initiative in Latin America and is republished through a partnership with LADO B.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.