Trans people and silicone implants: between dangers and the right to identity

The lack of access to healthcare for trans women and the unregulated plastic surgery creates lifelong problems. It represents exclusion from the right to health and identity.

Share

Surgeries and body modification procedures for transvestites and trans people are not merely "aesthetic," but in many cases, an "essential" part of identity construction. This was highlighted by individuals who chose to modify their bodies in Presentes. However, it is an uphill battle for this community, which, due to a lack of resources or exclusion in healthcare and employment , has resorted to unsafe practices to achieve this.

The role of the State in guaranteeing interventions, the regulation of plastic medicine, and initiatives such as harm reduction are some of the aspects proposed to address this problem.

Presentes spoke with trans women and health professionals about the situation in Argentina and Mexico.

“I’ve been sleeping in a lot of pain for about three years now.”

“In 2000 I left Tabasco. I was a prostitute, but I wanted to earn dollars to get butt, hip, and breast augmentation, like a doll. I injected my buttocks and legs with mineral oil and other things I don't know what they were. In the United States, I had more work done. I had the body I dreamed of, but for the last three years, my skin has felt hard, and I sleep in a lot of pain .”

The narrator is Deborah (the source requested a name change). In 2021, after health complications—resulting from 17 cosmetic procedures—she returned to Mexico because, she says, if she dies, she prefers it to be in her own country.

Deborah laughs nervously when she talks about death. When asked why, she replies: “ We know the risks. Maybe it’s not immediate. In my case, it took years, but I’ve lost friends to this—thrombosis, their skin rotting, and they dying. It’s awful. We endure the pain because we’re also ashamed.”

Patricia Alexandra Rivas lives in Becca, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. She is a 57-year-old trans woman who has liquid silicone implants in her buttocks, breasts, lips, and cheekbones. As is often the case, the silicone was injected by an acquaintance.

“A friend applied the silicone at her house, which was very clean and tidy, and she treated me very well. I went with her because I was going to go to a professional who would do the same thing and charge ten times more . It was out of my budget,” she shared with Presentes about her experience.

Patricia now strongly advises against these types of procedures because they had negative consequences for her. “It gave me premature osteoarthritis in my spine and hips, which prevents me from walking. I can walk two blocks and I can't take any more of the pain,” she said.

In this regard, she would like to see a "very strong campaign" that says "no to silicones and industrial polymers ." She also pointed out that "there are now hormonal treatments or, if necessary, prostheses."

The right to health is not guaranteed for trans women

Deborah and Patricia's experience with body contouring products is not an isolated incident. They say that all their friends, trans women younger than them and in their fifties, have used these types of substances at least once in their lives, including hormone therapy without medical supervision.

In Argentina, 83% of transgender women have modified their bodies to align with their self-perceived gender identity . This is according to the report "Socio-Sanitary Conditions of Transgender People," published in 2019 by the then Ministry of Health and Social Development.

Regarding the type of procedures, half involved injecting materials into the body. Liquid silicone was used in 66% of cases, and airplane oil in 17%, while breast implants were used in 3 out of 10.

According to the 2021 Survey on the Sexual Health of Trans Women in Mexico conducted by the National Institute of Public Health (INSP) , 80% of trans women used feminizing hormones. Of these, two out of three did so without medical supervision. The questionnaire did not include questions about the use of body fillers or biopolymers.

Why is access to healthcare being demanded?

In Mexico, the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) treats what they call "disease caused by cartilage in its specialty hospitals." According to figures from the General Hospital, in 85% of cases, no alternative could be offered due to the advanced stage of the damage, and patients were only treated with pain management measures.

However, there is no official data on the use of biopolymers in transgender women . Consequently, it is unknown to what extent these substances are related to these deaths resulting from denial of their right to health. The Mexican state does not guarantee comprehensive healthcare for transgender people.

Transgender people in the Americas are systematically denied access to professional health services, including gender-affirming services, due to mistreatment, pathologization, and discrimination within the medical field. Furthermore, they face economic barriers when these services are available outside of public coverage. This is documented in the 2020 report " Transgender People and their Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Rights" prepared by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

“ These circumstances prevent trans people from accessing safe body modification processes , which has led to premature and preventable deaths resulting from unsafe and clandestine procedures throughout the region,” the IACHR report states.

“It’s not a whim; it involves many spheres, including identity.”

For sex worker and human rights advocate Natalia Lane, the decision by trans women to use these substances stems from several factors. But she insists that " it must stop being viewed through the lens of revictimization and punishment, and instead focus on understanding the lived experience and specific contexts."

“This isn’t a situation that only affects women who survived the dictatorships and police harassment from the 70s to the 90s. Young trans women of 18 and 19 are also infiltrating the scene because it’s not merely about aesthetics. It touches on the construction of identity, on recognizing ourselves as women, because there’s also a demand stemming from aesthetic violence to meet certain beauty standards ; but also, in very specific contexts like sex work, it involves your own survival and having a job,” Lane adds.

Corporate responsibility

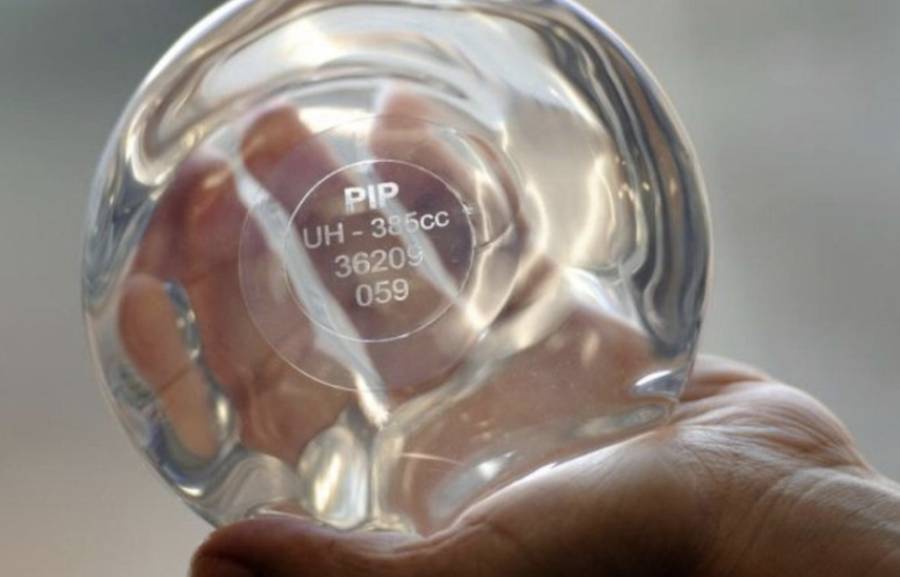

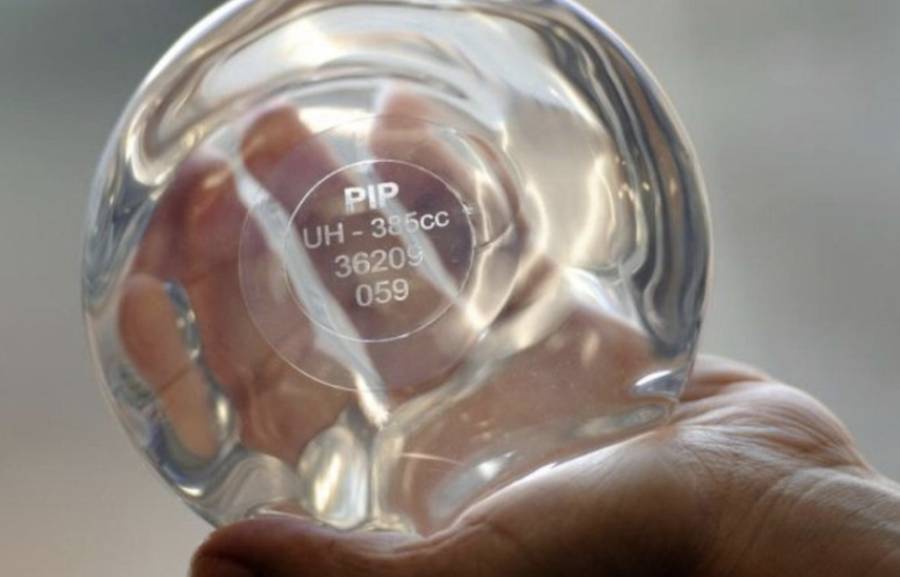

Far from being a local problem, unsafe cosmetic surgeries and procedures transcend borders. In 2011, a scandal erupted in France due to the high rupture rate of breast implants manufactured by Poly Implant Prothèse (PIP), which had been certified by the German company TÜV Rheinland. The implants were defective, with a rupture rate seven times higher than other implants. Furthermore, they contained industrial-grade silicone unsuitable for medical use.

When their danger was confirmed in 2011, their sale was banned. But between 2001 and 2010, around 500,000 women and gender-diverse people worldwide used these defective implants.

One of them was Vanesa Luciana Ojeda, a 39-year-old trans woman from the Buenos Aires town of La Matanza (Argentina) and a territorial promoter at Casa Diana y Lohana .

“I had them in me for ten years. Then I had the complication of my PIP implants rupturing. I felt like they were shifting internally, but I didn't pay much attention to it. I felt a strange warmth. Hours later, after finishing my workday, I got home and took out my clothes and saw that one of my implants was twice the size. I was terrified and didn't know what to do. I was extremely depressed for a while and was left with the fear that it would happen to me again,” Ojeda told Presentes

In France, a massive international lawsuit was launched seeking justice for half a million victims in 60 countries. The Paris Court of Appeal upheld the German certification company's liability on appeal. Following this decision, thousands of affected individuals received compensation.

Within this framework, the #YouStillHaveTime campaign was launched so that people worldwide who may be victims of PIP breast implants can join the mega-cause. To do so, they must have their PIP implant certification and contact the WhatsApp number +54 9 1130762737.

Ojeda hopes that this legal process will result in those responsible "compensating all the victims with a high amount, since it was not only aesthetic but there was also a risk to life and psychological consequences, leaving lifelong scares."

The penalty does not stop the application

In 2022, Mexico City reformed its Penal Code to establish a prison sentence of 6 to 8 years for the crime of homicide or injuries "to anyone who injects or applies unauthorized modeling substances for aesthetic purposes and causes damage or alterations to health, temporarily or permanently."

For Natalia Lane, creating criminal offenses against trans women who use these substances could endanger them. “Many of my trans colleagues have, in a way, become professionals in injecting these substances. Of course, not through the institutional lens of cosmetic surgery, but out of a desperate need for economic survival. A crime won't stop women from injecting biopolymers. What's needed are risk reduction programs and for the State to guarantee their health ,” she added.

Regarding regulation, a reform has been stalled in the Senate since April 2023 .

In 2022, José Luis García Ceja, Director General of Quality and Education in Health at the Ministry of Health, said during the forum "The current state of cosmetic surgery in Mexico " that "for every certified plastic surgery specialist, there are between 20 and 25 people who perform so-called cosmetic surgeries without being trained and in unsanitary places that put health and life at risk."

During that forum, trans congresswoman Salma Luévano shared her experience with the use of body-shaping agents and warned : “These practices that are costing us lives cannot be allowed, but the State also has to provide protection, guarantee the health of trans people […] we are a precarious group that cannot afford medical services, much less surgery […] This is not about whims, it is about life, about health.”

“Risk reduction plans are needed”

In Mexico, there are three public clinics that provide medical care to transgender people. All are located in Mexico City, and only the Comprehensive Health Unit for Transgender People (USIPT) has a holistic approach . The community area coordinator, Oyuki Martínez, explained that they offer peer support spaces where the issue is addressed from a harm reduction perspective.

“We discuss safe procedures with specialists and, if necessary, refer patients to a second- or third-level hospital. Recently, we have also been working with the dermatology department, to the best of our ability, to treat injuries caused by the use of biopolymers,” explains Martínez.

Daniela Muñoz is a surgeon and founder of TranSalud , a community of healthcare professionals who provide comprehensive care to transgender people. She believes that risk reduction also involves sharing information without prejudice.

“To talk about harm reduction, it’s important to change the narrative. We can’t criminalize those who decide to do it; it’s a public health issue that the State has refused to address despite the existence of the trans health protocol . ”

In the province of Misiones, Argentina, a public policy was proposed to address the health situation of the trans community and find solutions regarding the injection of harmful industrial oils. Based on data collected in 2014 by the LGBT Misiones Association on Access to Healthcare for Trans People, strategies were designed to address various barriers, and the serious health situation faced by trans people was brought to the attention of the provincial health authorities.

In a meeting with the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Oscar Herrera Ahuad —current governor of the province of Misiones—, Matías Jesús Ríos, who was in charge of the Department of Diversity and Identity of the Ministry of Human Rights of the Province of Misiones, told Presentes that the then minister committed from the ministry “to remove the industrial oils that had been placed on the target population – as far as possible – and replace them with prostheses approved by ANMAT (National Administration of Drugs, Food and Technology) in the Public system.”

Some of the women interviewed agreed that the use of industrial oils was discouraged, and they emphasized the need for qualified information on body shaping. Furthermore, they stressed the importance of the State guaranteeing safe practices, as these are not merely “aesthetic” issues, but rather matters of identity.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.