What is hate? Why is this word used to talk about violence against LGBTI+ people?

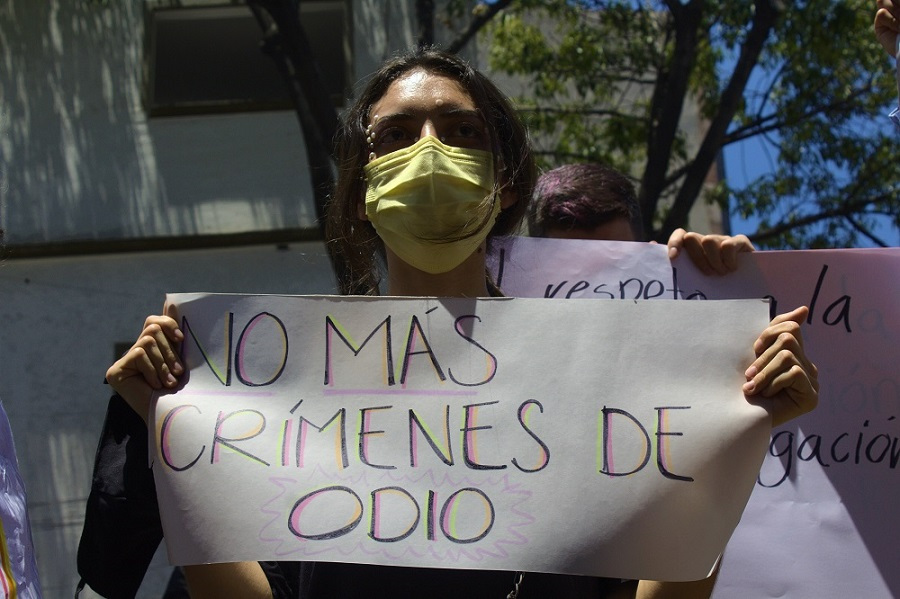

May 17th is the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia. Are there better words to describe the violence suffered by LGBTI+ people? Six activists from Argentina and Mexico reflect on the issue.

Share

The International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia is also called the Day Against LGBTI-Hate. What is the difference between these terms, and what tensions does this create within activism? Are there better words to describe the violence suffered by LGBTI+ people? “Hate crimes” is a legal concept coined in the United States to describe violence motivated by sexual orientation, gender identity, or perpetrated against ethnic or religious groups. Racism, for example, is a hate crime. One of the characteristics of this type of crime is that by acting against a member of a particular group, a threat is sent against that entire group.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) chooses to refer to these crimes as “bias-motivated violence.” Unlike the term “phobia,” which alludes to an extreme fear and, in some ways, a pathology, or the word “hate,” which appeals to an emotion, prejudice as a concept is easier to identify, trace, and therefore combat. “ This context of prejudice, coupled with the failure to adequately investigate these crimes, leads to a legitimization of violence against LGBT people and has a symbolic impact,” says the IACHR.

Presentes consulted activists in the region about the use of terminology and the scope or limitations of language when referring to these forms of violence. We asked them two questions:

1- Why are we talking about hate crimes?

Siobhan Guerrero , researcher and philosopher of science, Mexico

I would like to clarify that we are not talking about hate in the sense of referring directly to hate as a psychological state of someone who commits a crime, because if we made that move, which is perhaps what common sense would expect, we would have an epistemological problem.

I think we need to distance ourselves from the notion of emotions as individual psychological states and think of them instead as affective issues that govern the logic of interaction between bodies.

In this sense, we speak of a hate crime, because it is not a crime committed against an individual in their richness and fullness as a human being, but rather against an individual who is being subsumed and, in a way, dehumanized by being placed within a negative stereotype. This stereotype, of course, mobilizes a series of symbolic elements that reduce the person to a stereotype that is interpreted as threatening, dangerous, despicable, inhuman, and that must be destroyed. And it is in this sense that this stereotype does generate emotions within social dynamics, within the logic of exchange and interactions between bodies, leading to violence against those who are thus subsumed under a stereotype.

Alba Rueda, Special Representative of Argentina on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship

It is one of the terms used to internationalize violence against LGBTQ+ people. Originating in the United States, "hate crimes" allowed for the capture of the expression of violence against LGBTQ+ people. It also draws attention to identifying this violence in relation to structural forms of violence, which are situated not only in the crimes themselves, but also in a web of social situations, prejudices, and stereotypes through which the dehumanization of LGBTQ+ people circulates.

It's a fundamental concept that allowed for the identification and classification of crimes. In Argentina, the aggravating circumstance of hatred based on sexual orientation or gender identity is included in the Penal Code. This was the aggravating circumstance applied in the trial for the transphobic murder of Diana Sacayán. It's undoubtedly a step we've been working on, and it's important. But it's also a concept that's beginning to expand. There's a growing awareness of the dimension of hate crimes and hate crimes, which don't diminish the other aspect but rather seek a more precise expression of it.

Violeta Alegre , trans activist and Head of the Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Office – Gender Observatory in the Justice System of the City of Buenos Aires

It's a challenging question, and I'm glad we're considering it because hate is often used as a link in the chain that perpetuates certain crimes, and we don't talk about the entire system that shapes the very fabric of those crimes. But there's what comes before. Let's say that hate is a consequence of something that precedes it. We can think of crimes as being motivated by hate because there's an entire society that is both vilifying and delegitimizing a group, sending the message that if you attack an LGBTQ+ person, nothing will happen. Legally, this is important when it's considered an aggravating factor, as was the case in the transphobic murder of Diana Sacayán.

Alejandro Mamani , lawyer specializing in human rights, Argentina

It's important to emphasize that certain types of crimes have motivations that require their classification to consider specific issues. Regarding hate crimes, in the Argentine or Latin American context, we can speak of aggravating factors. That is, how certain types of socially committed crimes can have aggravating factors related to gender, gender identity, gender expression, ethnicity, race, or sexual orientation. These aggravating factors have a spectrum that differs even further from the classic definition of these crimes. In that sense, I'm more inclined to speak of crimes with aggravating factors. And to understand that social aggravating factors in each country have their own particularities. Therefore, talking about hate crimes is the starting point for discussing specific crimes with certain aggravating factors in cases of sexual orientation, gender expression, or ethnic-racial characteristics, or gender identity. What we're really talking about is a factor of social contempt toward a group, in some cases. This rejection, this hatred, as some cases describe it, is an aggravating factor when it comes to the cruelty inflicted upon certain bodies , and the law must consider it because it stems from an even larger structural issue. In that sense, it seems to me that there is a kind of corrective action within the system against those deemed deviant. And that's where crimes against homosexuals, lesbians, or transvestite and transgender people come in.

Samuel Martínez, coordinator of the research area at Letra S , an organization that has been documenting the violent deaths of LGBTI people in Mexico for more than two decades.

At the beginning of our reports, we used this category because it seems to be much more common in Mexico; people understand what we mean when we talk about hate crimes. However, what we are seeking with the 2022 report is to reposition and discuss this category, to shift from simply thinking of hate as hate itself, to understanding that hate is based on collective prejudices, that hate is social, that it has a cultural basis, and that this cultural basis is what legitimizes these types of attacks.

That Montenegro , a trans male activist, teacher trainer in Comprehensive Sexuality Education and advisor to the Chamber of Deputies of the Nation

It's part of a political construct of LGBTI groups. At one point, it was discussed as a phobia, a phobia understood as a synonym for fear of the unknown or the ignored. Later, it was understood that it's not actually a matter of fear of the unknown or the ignored, but rather hatred of difference, let's say, as a social resistance to difference. And from that resistance comes the production of social meanings that, in some way, promote hatred. And this isn't specific to the LGBT community. The narrative of hate, if one thinks about it critically, is also found or located in racist discourses; the narrative of hate permeates classism, even if we think about it in terms of political violence and the situation, for example, of reaching an attempted assassination of a vice president of a state, as happened here, I mean. There's a whole social construction of that narrative that dehumanizes the person subjected to that hatred and enables, to varying degrees, to a greater or lesser extent, hatred. And that hatred translates into concrete actions, into more or less subtle forms of discrimination, or in a much more radical way in what can be expressed in a transvesticide, a transfemicide, a transomicide, a lesbicide.

2- Does hate explain the violence suffered by LGBT people, or is there a better word that you think is more appropriate to express this violence?

Alba Rueda: Over the years, there have been and continue to be different perspectives highlighting that this expression of hate crimes has certain limiting conditions. For example, along the same lines, Latin American experiences, and those in Argentina in particular, began to establish, especially within the judicial sphere, the concept of crimes motivated by prejudice or discrimination.

Because in various trials involving hate crimes, many of the difficulties in legal terms lie in proving the inscription of hate. In other words, defining how hate is inscribed within this framework of violence is often what prosecutors or defense attorneys object to. They argue that there is no clear definition of what constitutes hate within the ways these crimes are committed. Therefore, using terms like prejudice and discrimination allows for a more accurate description of the complex web of situations and prejudices that also exist in the social sphere and that contribute to violence and its inscription on the bodies of lesbians, gays, and trans people.

Siobhan Guerrero: I would say that hatred can play a role, although it's not actually the only political emotion. I think there are other political emotions, like disgust and contempt, that also generate stereotypes, that also dehumanize, that also ignore the singularity and uniqueness of the other, that reduce them in some way to a negative symbol. I don't think hatred is always a sufficient explanation. I think there may be other kinds of political emotions at play.

I don't know if there's a single word that could encompass them all. Perhaps the closest would be to talk about crimes fueled by political emotions and stereotypes, but that phrase isn't as easy to use as "hate crime," which I think communicates something that goes viral more easily.

And of course, this doesn't mean that each and every crime suffered by an LGBT person is a hate crime. But I would say that some crimes are clearly motivated by the social interpretation of the other as a mere stereotype. And here, I would not only allude to affective shifts in gender studies, but also to symbolic interactionism, which states that unfortunately, our interactions with others are often mediated by stereotypical representations of different social groups.

Montenegro: I don't know if the narrative, explanation, or justification based on hate crimes fully encompasses the problems of the LGBTIQ+ community. It seems to me that each experience, each life journey, has its own specificities. It's not the same to be a lesbian, a cisgender person, as the structural violence we face is the same. In that case, the first agent of resistance is heteronormativity, and there we can talk about heteronormativity, heterocentrism, as the site of domination from which violence is exercised.

The concept of hate crime ultimately encompasses the structural issues. I think there's a historical undertaking there, one that has been developing from the margins, but which also intersects with the struggle for human rights. When the role of the State, civil society, the clergy, and businesses surrounding the dictatorship in Argentina began to be examined, the systemic nature of the problem emerged, and it was within this systemic framework that concepts like dehumanization began to be explored, and how dehumanization enables the extermination of those who are not considered human.

I think there's something about communication strategy that's useful when talking about hate crimes, but it works to the detriment of other issues, such as addressing the specific problems we still need to address. It's these specific issues that shift the focus of the problem. We can no longer keep putting trans people under the microscope; what we need to focus on is cissexism: how it's practiced, how it affects us all, how it's a mechanism that conditions us all to a greater or lesser degree, and how to dismantle it.

Violeta Alegre: A better expression, in my opinion, to describe the violence against transvestites and trans people is: transphobic or transphobic crimes. I think we need to stop focusing on trans or LGBT people—the same goes for the term “self-perception,” which I wouldn't use anymore—and instead focus on the external source of this violence.

Alba Rueda: Over the years, various perspectives have drawn attention to the fact that this expression, "hate crimes," has certain limiting conditions. For example, along the same lines, Latin American experiences, and those in Argentina in particular, began to establish, especially within the judicial sphere, the concept of crimes motivated by prejudice or discrimination. Because in various trials where hate is involved, many of the difficulties in legal terms lie in proving the inscription of hate. That is to say, defining how hate is inscribed within this framework of violence is what prosecutors or defense attorneys often object to. They argue that there is no clear identification of what constitutes hate within the ways in which these crimes are committed. Therefore, using terms like prejudice and discrimination allows for a more accurate description of a web of situations and prejudices that also exist in the social sphere and that also contribute to the violence and the inscription of this violence within the bodies of lesbians, gays, and trans people.

Samuel Martínez: Hatred, understood as an individual disposition, does not explain these types of crimes, which are gender-based violence rooted in cultural predispositions. However, understanding hatred as that cultural and social construct rooted in prejudice, stigma, and negative and violent predispositions allows us to understand how these crimes are not committed by individuals, but rather are materializations of negative conceptions present in society.

So what we are looking for (in the report) is that transition from hatred to prejudice, not because they are different, but because we believe that prejudice expresses much better the idea that hatred cannot be understood as an intention, as an individual disposition, but with that rooted prejudice and violence, which is behind the crimes committed against the LGBTI population.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.