Mexico: How the struggles of the LGBT+ movement and HIV activism were plotted

Three activists and protagonists of a collective construction that has a history of more than 40 years.

Share

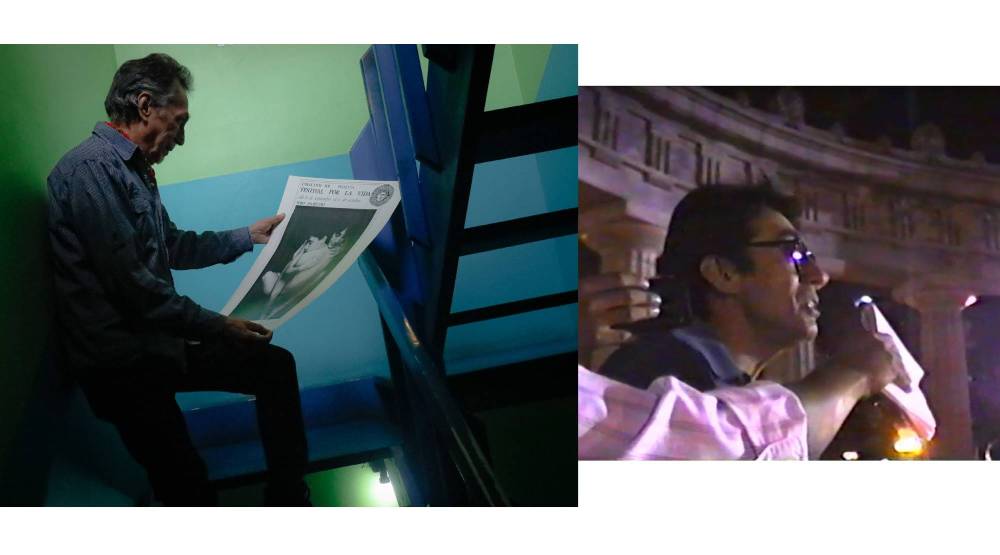

The epidemic took the LGBT+ movement in Mexico by surprise in the 1980s. “We had liberated ourselves in many ways and suddenly, boom!, AIDS appeared to strengthen all the reactionary discourse against our lives, our practices, and who we were. It was a very hard blow,” says Rafael Manrique, a photographer who participated in the beginnings of the Lesbian-Gay Liberation Movement , so named in the 1970s.

HIV/AIDS arrived as a rumor. There was disbelief, but cases began to emerge. Faced with this, the sexual dissident movement had to react. “You couldn’t remain silent because you were in the eye of the storm… It was difficult, it was very painful for many people. Especially for those who already had HIV at that time and whose prospect was death, with very few survivors. We who are here now,” shares Juan Jacobo Hernández, co-founder of the Revolutionary Action Homosexual Front (FHAR 1978).

There was confusion and uncertainty. “There was no one to give you information. I was afraid of people’s reactions because I was beaten up a few times on the subway, spat on a few times in the street, and people yelled terrible things at me. I was scared and angry,” says Flora Lugo, a trans actress, showgirl, and designer.

Following the organization, Juan Jacobo Hernández and other activists formed Colectivo Sol , AC in 1981, which has since focused on promotion and activism to prevent HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, as well as working in defense of the civil and political rights of the homosexual and transvestite (now trans) population, mainly.

To restore civil and political rights

Colectivo Sol brought together various initiatives that included silent marches, vigils, the publication of the magazine Del otro lado , which included telenovelas made by Rafael Manrique, and it sheltered the start of the Condomóvil , which remains active and is managed by the activist Polo Gómez.

“We drew on all the wealth of experience we had accumulated from the homosexual liberation struggle, as it was called back then. It was a fight for life, for the dignity of people,” Hernández points out.

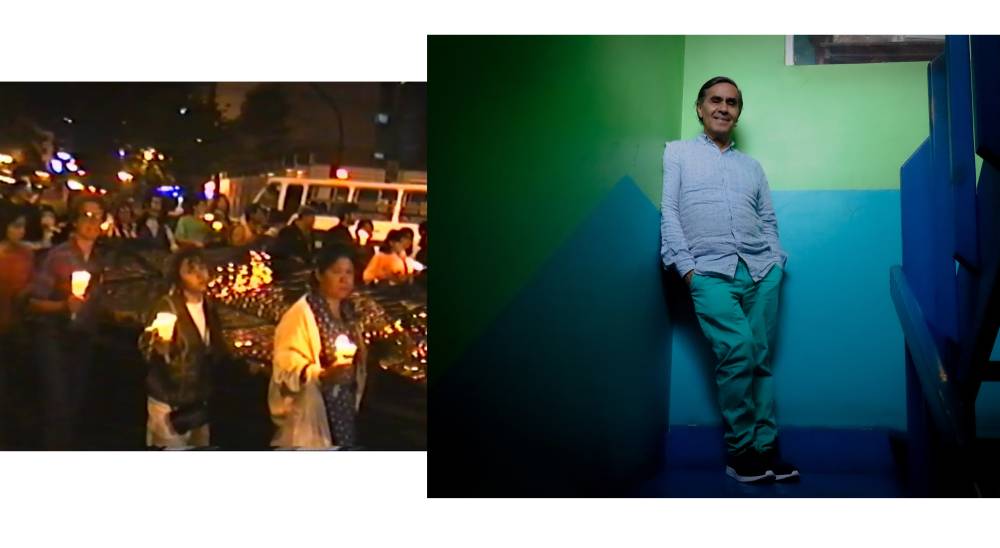

Right photo: Rafael Manrique.

Epidemic and prejudice

Just over 40 years after the arrival of HIV/AIDS, the response to other epidemics has varied in Mexico . Rafael Manrique points out that the response to Covid-19 (2020) was immediate at all levels and was not fraught with stigma and prejudice.

The same did not happen with monkeypox, mpox—the name the World Health Organization has recommended using —which spread worldwide from mid-2022 and was declared a “ public health emergency of international concern ” by the WHO. The response in the country has been insufficient, fraught with stigma, and lacking the will to acquire and distribute vaccines, activists have denounced .

From the outbreak in 2022 to April 17, 2023, there have been 87,039 confirmed cases of mpox and 120 deaths, according to the WHO's multinational monitoring

Among the Latin American countries with the most cases are Brazil (10,900), Colombia (4,090), Mexico (3,956) and Peru (3,800).

In Mexico, five deaths have been recorded, and there are 6,687 probable cases. The highest number of confirmed cases is concentrated in Mexico City (2,036), Quintana Roo (241), and Yucatán (169). According to the Ministry of Health 's surveillance report

That's why it's worth remembering.

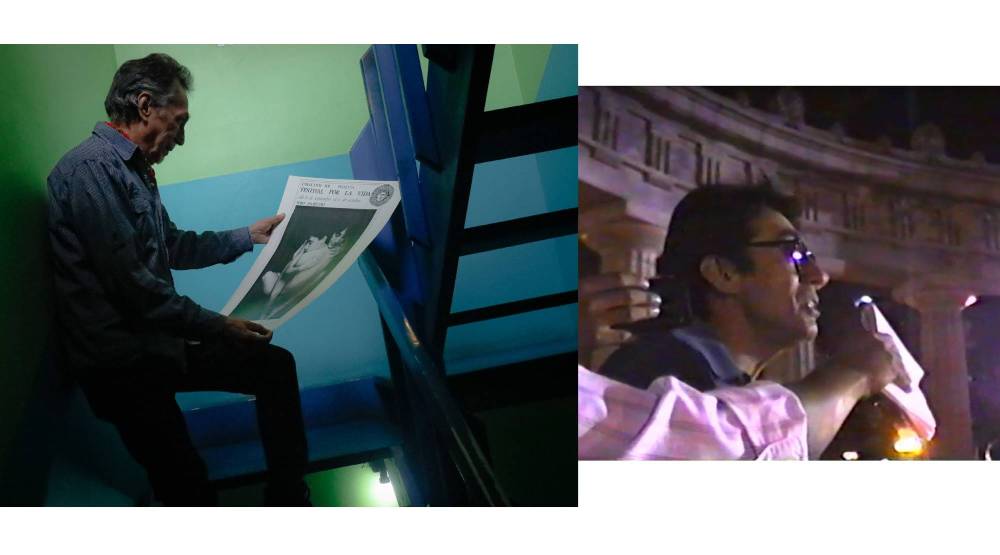

Right photo: Night walk for those who died from AIDS, November 1991.

Courtesy of Colectivo Sol.

Let us not forget the past in order to shape the present and the future.

Juan Jacobo Hernández says that HIV activism is a commitment. In his more than 40 years of work, he has seen that “discrimination, prejudice, and ignorance persist.” This also occurs in the face of new health emergencies like mpox. “We see the government’s refusal to provide the vaccine; it is the only country with so many deaths and so many mpox cases that lacks a disease management strategy.”

In addition to government indifference, Hernández observes that the LGBT+ movement is currently fragmented and insufficient attention is being paid to what is happening in areas beyond Mexico City. In the 1980s and 90s, concepts such as “solidarity, community work, and the empowerment of people” were important to the movement.

Rafael Manrique shares that at the beginning of the LGBT+ liberation movement, there were other goals that sought to "establish a new way of living in society" and were not limited to access to marriage equality. He also emphasizes the importance of observing what happens in communities, saying, "If you go to poor communities, you realize what it's like." Manrique has lived much of his life in Barra de Chachalacas, Veracruz, where he has seen how urgent issues regarding sexual rights are not the same in small towns as in large cities.

Another aspect that was relevant to HIV activism was the creation of international networks. At the time, these allowed for an expansion of the LGBT+ movement and the systematization of best practices for prevention. But “that effort suddenly disappeared,” Manrique comments.

Flora Lugo describes activism as a way for her to counteract fear and misinformation, to realize she could "do something." However, during those years, she was aware of her circumstances and had to choose between continuing her activism and finding employment or other ways to make a living. She had to prioritize the latter, but now, whenever possible, she shares her experience as a trans woman and the risks she faced with younger generations.

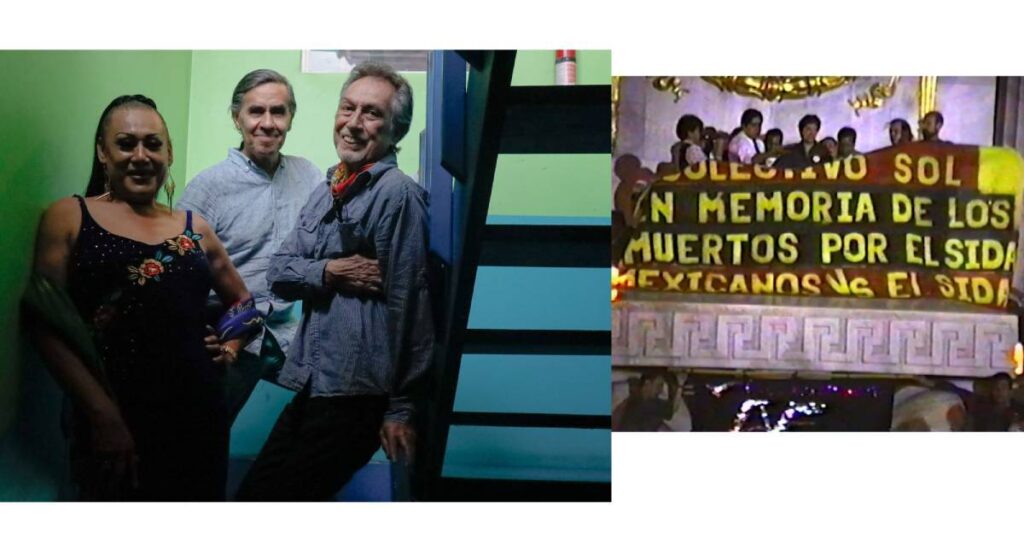

Right photo: Juan Jacobo Hernández, co-founder of the Revolutionary Homosexual Action Front (FHAR) and founder of Colectivo Sol. Hemiciclo a Juárez, Mexico City. Night march for those who died from AIDS, November 1991. Courtesy of Colectivo Sol.

Right photo: Flora Lugo.

What's urgent now

For Juan Jacobo, Flora, and Rafael, the current situation is complex because within the LGBT+ movement there is division and fragmentation, and it is necessary to address what is happening in other entities outside of Mexico City.

“The most powerful movement right now is the trans movement; it’s the movement that hasn’t abandoned its grassroots, that asserts its needs and demands […] There’s no longer a gay or lesbian movement, because they don’t mobilize people. The trans movement does, and it’s the most mistreated movement, the one that causes the most exclusion, affecting those at the grassroots level, those who have entered politics, and those at the top,” Hernández points out.

Given this situation, it becomes important to look to the past, to consider what was done and what was lacking. Part of Flora, Juan Jacobo, and Rafael's work is included in the exhibition Positive/Negative: Cultural Adherences in the Fight Against AIDS in Mexico , a groundbreaking exhibition in the country that provides context on the fight against HIV/AIDS and on the role of art and culture in bridging generations.

“From the beginning, defending health was a political struggle,” Manrique points out. Not giving in to oblivion is also a political struggle.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.