Karina Pintarelli, the first trans survivor of the dictatorship to receive reparations from the National State

He is a poet, he is 64 years old and for years he suffered persecution and police torture because of his gender identity.

Share

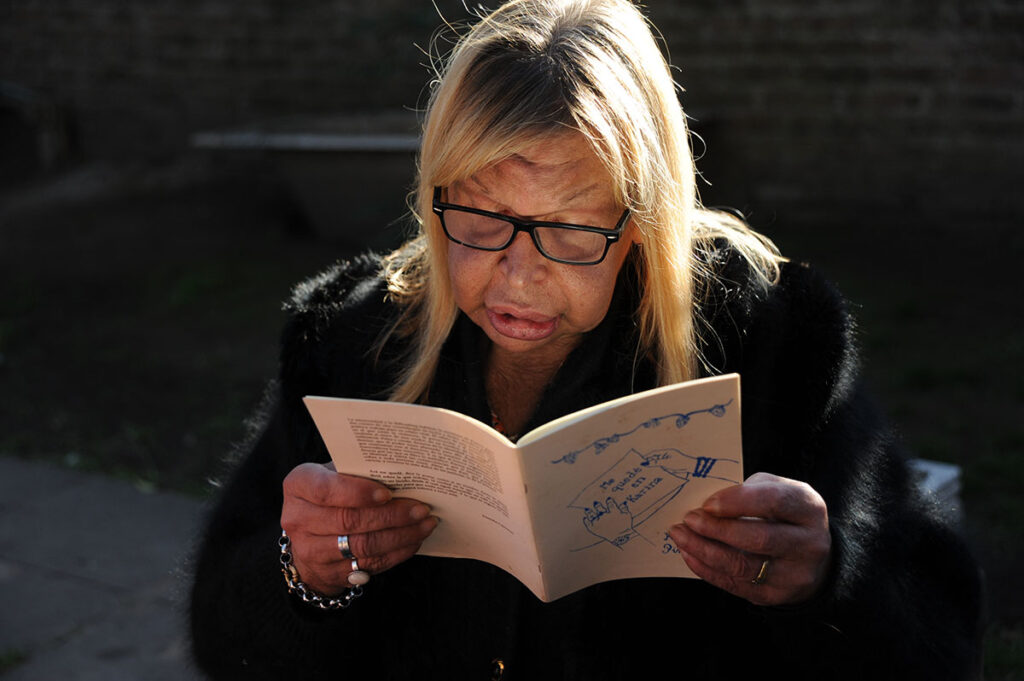

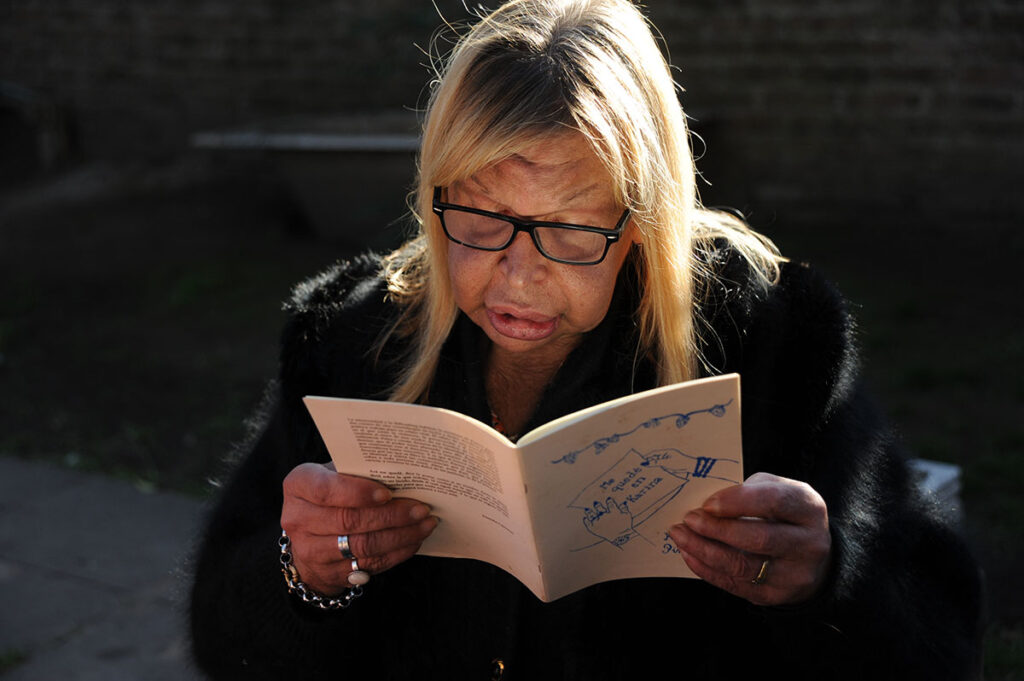

In the house in Merlo that she shares with three friends, trans activist and poet Karina Pintarelli is now resting. She knows she is a survivor: she is 64 years old and her life has been marked by multiple forms of violence, etched into her skin. On July 15, while she slept, the envelope arrived with the news that brought an end to her five-year struggle. The Ministry of Justice and Human Rights recognized the violence and persecution she suffered because of her gender identity during the last military dictatorship. She thus became the first trans person to receive this type of reparation from the national government.

“I can tell this story while I’m still alive. This is a recognition of what we went through. I’d like to share what we experienced then and what we’re experiencing now. To my friends, I want to say keep fighting, because by fighting, you can achieve anything,” says Karina, sitting in the garden of “Casa Leonor,” where she lives with Morena, Agustina, and Cielo. She met the three women—also trans—at the “Frida” center, a shelter for women and LGBT+ people experiencing homelessness.

The lives of Karina

Karina has lived many lives: a childhood in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Paternal with her mother, Irma, who was Basque, and her siblings, Mario and Liliana. She lived on the streets at times; other times, in Europe. She also lived in shelters, police stations, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals where she was placed to share spaces with men. She worked as a prostitute from the age of 22. She was both a client and a client. She lived and worked at the Frida Center, run by No Tan Distintes, between 2015 and 2018, an organization she is still part of today. She wrote poems that portray her experiences, which she compiled in the book I Stayed in Karina (2019).

Currently, she is one of the few transvestite and trans people still alive to tell her story of what she experienced during the dictatorship (1976-1983). And even in the democratic period, when violence against the community did not cease.

“I lived like a prisoner. I would spend 30 days inside, be released for a few days, then be arrested again for another 30 days. I went from police station to police station, spending four or five days there waiting to be transferred to Devoto prison,” she tells Presentes, holding a mate gourd and wearing a black sweater to ward off the winter chill. And she asserts: “It was because of my identity.”

In 2018, she conceived the idea of doing something with her memories. While using her thirty minutes of computer time at the Frida Center, she read a news article about a trans woman from the province of Santa Fe recognized by the provincial government as a survivor of the dictatorship. This recognition was granted under Provincial Law 13.298, which establishes a monthly pension for individuals who can prove they were "deprived of their liberty for political, union, or student-related reasons" between March 24, 1976, and December 10, 1983.

“I read that a trans girl in Santa Fe had the repair done, and I came wanting to do something, but I didn’t know what, how to start, what tools to use. Until I told Flor what I wanted to do, and that’s when the fight began,” says Karina.

“Flor” is Florencia Montes Páez, a political scientist and founding member of the organization No Tan Distintes (NTD), which works “with, by, and for” women and LGBTQ+ individuals experiencing homelessness. In its 11 years of existence, NTD carried out various initiatives, including the creation and management of the Frida integration center. They no longer run that project, but it gave rise to others, such as the Leonor house.

“When Kari started all this, we had nothing. We went to build it, to see how the repair could be done, if it was even possible. Now we call it 'repair,' before we didn't know anything at all,” says Florencia, recalling that time.

The search for evidence

That year, Karina began receiving support in her fight from the Gender Observatory in the Justice System of the City of Buenos Aires, and the organizations NTD and Lawyers for Sexual Rights (AboSex). The latter, in 2015, had launched the “Recognizing is Repairing” campaign, along with more than 200 other organizations. This initiative proposes a law that provides reparations to victims of institutional violence based on gender identity.

Thus, the first action they had to take—and the most difficult—was to gather evidence. “We went to look for three files: one in the province of Buenos Aires, one from the prison service, and another from the Federal Police. The one from the province of Buenos Aires was eaten by rats, they told us, so we didn't get it,” says Montes Páez.

Finally, they found the Federal Police file. “A file like this (she gestures, separating her index finger from her thumb about 10 centimeters), whose title was 'Pederast.' It was created in the late 1960s, and the last entry in his record is from 1996. Thirty years of criminal record,” Florencia explains.

“Karina’s case file is shocking, and not pleasantly so, because it serves as living proof of the systematic nature of arrests based on police edicts. This essentially demonstrates the violence and criminalization of gender identities,” explains Sofía Novillo Funes, a lawyer and member of AboSex. She is referring to the edicts issued by the Argentine Federal Police, specifically sections 2F (public indecency and incitement to sexual acts) and 2H (wearing clothing contrary to one’s sex).

For the test, it was also “very important to have a first-person account of the events experienced by Karina,” Novillo Funes adds.

Art with handbooks

With the collected materials and the awakening of memories, Karina created a multifaceted work called “Time in My Hands.” It consisted of the book of poems * I Stayed in Karina* , which the Serigrafistas Queer collective used to create a visual piece. It also included an audiovisual installation curated by Mariela Scafati and Daiana Rose called *Prontuario* , which displayed part of the file. “I like to express what I feel, what I’ve lived through, my feelings. Everything that has been my life. There are many people in the same situation as me,” says Karina.

“With the imagery of the dictatorship, you might think she was in a clandestine center. No. Kari was picked up by the police and systematically taken to Devoto prison. She was in men's wings. She was tortured, all related to her gender identity, to punish her, discipline her, and hurt her. All with the approval of the dictatorship,” Florencia recounts.

In 2020, Karina, together with the Observatory and the organizations that accompanied her, presented to the National Secretariat of Human Rights a request for reparation for the violence suffered as a victim of state terrorism.

Finally, on July 15 of this year, the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights ruled in favor of Karina after addressing her complaint. The technical report from the National Secretariat for Human Rights confirmed “the persecution of transgender people as part of the National Security Doctrine.”

Other repressive tools

The report highlighted the “dynamic” nature of the comprehensive reparations policy and the role of the Federal Police within the context of state terrorism. It also emphasized the use of minor offenses as a repressive tool. Finally, it concluded that the State assumes “that trans women, in their embodiment of gender, were considered subversive agents.”

“This recognition in favor of Karina is a fundamental precedent and a great outstanding debt that still exists in relation to adult and older adult trans people,” Novillo Funes maintains.

In this regard, she emphasizes that what they experienced “was not only during the civic-military dictatorship, but that this criminalization persisted afterward.” She adds that “there are still provinces that have codes of conduct that criminalize gender identities.”

To recognize is to repair

“It is very important to listen to our colleagues and for the National Congress to pass the Recognize is Repair bill so that it dignifies and repairs the experiences of our transvestite and trans sisters,” she says.

Karina is calm, happy, and above all, resting. She spends her days with More, Agus, and Ciela at Eleonor's house, a place they were able to rent "at a reasonable price" and without any checks.

“I’m happy for Kari, for what she achieved and that she continues to fight today,” says Morena, a 31-year-old trans woman, who accompanies Karina to the psychologist every 15 days and also travels to bring her her medication.

“I get up, I cook for her, I wash her clothes, I see what she needs. One way or another, we're there for her because she's an elderly person now,” says Cielo (41), who arrived in Argentina from Peru 15 years ago. She's the group's cook, and that afternoon she was baking a chicken with potatoes.

“We live as a family, because that’s what we are. Kari is like my mom, she (Morena) is like my sister. The idea is to no longer have that street code with those petty squabbles. It’s difficult, but we’re getting there,” she adds.

At the end of the interview, Florencia recalls that earlier that day, they were thinking about what Karina's mother would say if she were alive.

What would I say?

"I would be happy, like any Basque woman. I would be happy to be recognized."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.