Monkeypox cases are on the rise; prevention measures and vaccines are lacking.

Mexico has one of the highest concentrations of cases. However, there is a lack of information, and what little there is generates stigma among the gay and bisexual male population.

Share

VERACRUZ, Mexico. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared monkeypox a global health emergency, which as of July 28 had accumulated more than 21,000 cases in 78 countries.

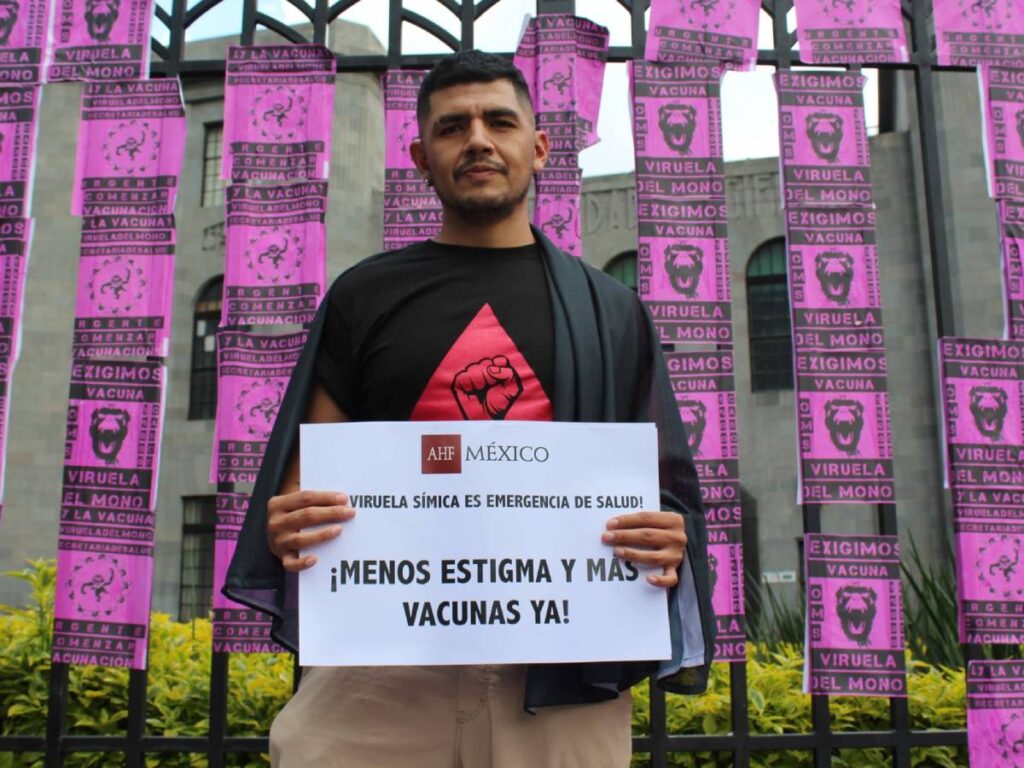

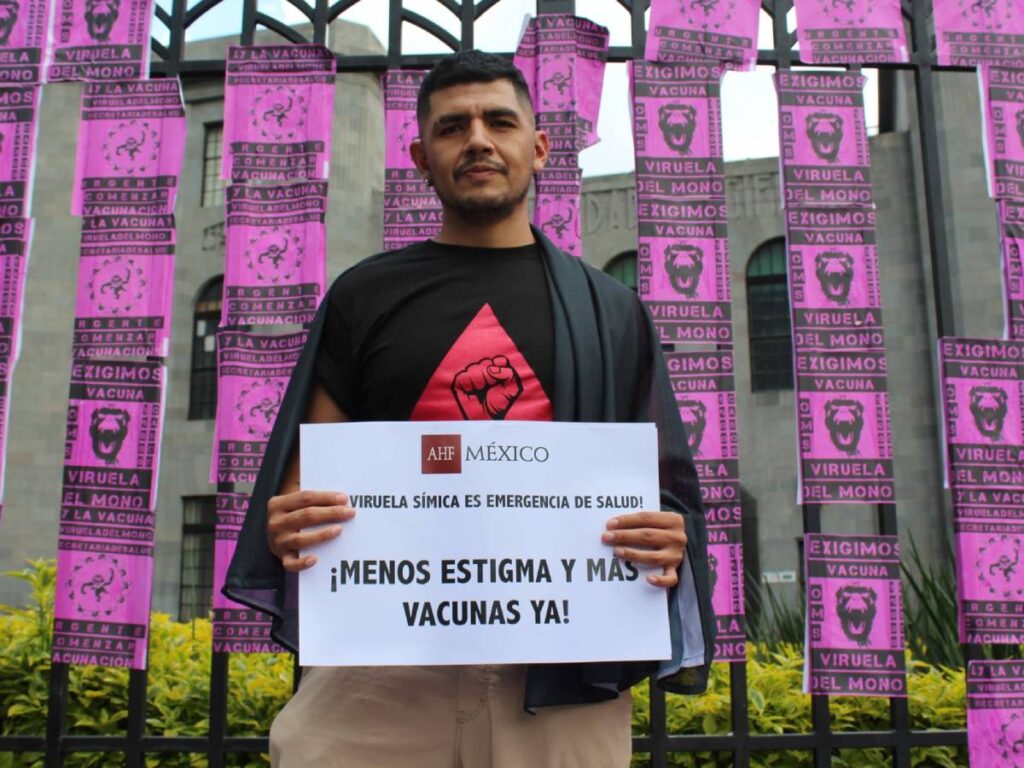

Recent scientific studies indicate that, at this time, the populations most affected by the outbreak are gay men, bisexual men, and men who have sex with men. In Mexico, activist groups are organizing, demanding stigma-free information and timely vaccination for at-risk groups.

The countries where the outbreak is currently concentrated are Spain, the United States, and England. In Latin America, Brazil and Peru have the most confirmed cases , with 978 and 251, respectively.

Mexico follows with 60, a figure that the federal government released two days after the WHO declared a global emergency, which the Undersecretary of Prevention and Health Promotion, Hugo López-Gatell, considers "not expected to spread extensively."

The organization against silence

Activists in Mexico are complaining that the government is taking a “slow” approach to monkeypox prevention. They also criticize the government’s “weak, heteronormative, and conservative” communication strategy, which they say prevents information from reaching the groups most affected. The truth is, the Mexican government is failing to communicate effectively with the general population about this disease.

Alaín Pinzón, director of VIHve Libre , an organization dedicated to supporting people living with HIV in Mexico, told Presentes that he learns of up to three new cases in a single week. He warns that government data may be underreported. He explains: “Gay men and those of us living with HIV have a history of stigmatized and discriminatory treatment at health centers, which leads to isolation and discourages us from seeking care at clinics.”

He added, “Some people are panicking because no one is talking about the fact that we are the group most affected. If we say that just because we're gay and living with HIV we're the most affected population, there's stigma. We have to explain why we're the most affected. The fact that the State withholds this information is like you don't exist for Mexican health policy, like you don't exist as a gay individual who lives and has sex with other men. As if that were wrong in their eyes (the government's). You feel so invisible and so sick at the same time that you think you're going to die, that it's fatal, even though it isn't.”

On Friday (July 29), the first two deaths from the new monkeypox outbreak . They occurred in Brazil and Spain; both individuals had weakened immune systems. In Africa, have been reported , according to the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC).

Photo: Georgina G. Álvarez

Monkeypox: what it is, what are the symptoms

Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease, meaning it is transmitted between animals, including humans. It was first detected in a child in 1970. Since then, cases have occurred, primarily in rural areas of Central and West Africa, but it is not exclusive to this continent. In the years prior to the current outbreak, cases were reported in the United States, Palestine, and Singapore, but these were contained.

In May 2022, the WHO detected new cases in countries without records and whose patterns are different from those that occur in countries where the disease is endemic.

- The symptoms: fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, lack of energy, and swollen lymph nodes.

- Followed by skin lesions that can last from two to four weeks and are characterized by being painful and evolving into scabs.

- Skin rashes may appear on: the face, palms of the hands, soles of the feet, eyes, mouth, neck, groin, genitals and perianal area.

Specialists working at the Condesa Specialized Clinic, the first community health center in Mexico to care for people living with HIV, warn that monkeypox skin eruptions can resemble some sexually transmitted infections such as herpes or syphilis and recommend seeking medical evaluation if you suspect any of these conditions.

Contact during sexual activity can be a route of transmission

The virus is transmitted from person to person through close and continuous physical contact with skin lesions caused by the disease. It can also be transmitted through saliva and respiratory droplets.

No health institution or organization in the world has proven that monkeypox is a sexually transmitted infection (STI). However, based on current knowledge, close contact during sexual activity may be a route of transmission.

This is highlighted in a study published on July 21 by The New England Journal of Medicine, which reports that “in 95% of people with the infection, transmission was suspected to have occurred through sexual activity.” It emphasizes that “sexual transmission could not be confirmed.”

Other forms of transmission include physical contact with objects contaminated with the virus, such as blankets, towels, bedding, sex toys, kitchen utensils, and frequently touched surfaces. Pregnant women can also transmit the virus to their fetus through the placenta.

- Monkeypox can be transmitted from the time symptoms begin until the skin lesions have completely healed.

- The duration of the illness is generally two to four weeks.

If you live in Mexico City, you can go to one of the two Clínica Condesa or to the Level III Health Centers located in each borough. If you are outside the capital, it is recommended that you go to the general hospital in your state.

What prevention options are available to us?

The current outbreak marks a trend that has been confirmed by several published studies, such as the one in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in which Mexico participated. The results determined that, of 528 infections detected in 16 countries between April and June, 98% were gay or bisexual men, and 41% of them were living with HIV.

And while few cases have been detected in children and women , activists are urging governments and health authorities to act accordingly by providing information, prevention, detection and vaccination to the community that is currently being most affected.

The WHO's general prevention measures include: isolation; avoiding skin-to-skin and face-to-face contact, including sexual contact, with anyone showing symptoms; washing hands; wearing a mask; and regularly cleaning frequently touched objects and surfaces. In addition, the organization's director specifically recommended that men who have sex with men "reduce the number of sexual partners."

Before the WHO director's recommendation was made public, activists consulted by Presentes commented that it could be a form of prevention, but they consider it important to be careful how it is communicated "to curb the stigma and improve prevention."

“Avoiding gatherings that include direct and sexual contact, and not going to meeting places, requires limitations that not everyone is willing to accept. But it's valid, and there's nothing wrong with those who decide to go down this path and promote it, as long as it's done with autonomy in mind, without judging, pressuring, or making people feel fear or guilt,” says Carlos Ahedo , a nurse and coordinator of Positive Health at the Yaaj organization.

For Ro Banda , co-founder of La Tribu , a peer-to-peer HIV collective, one prevention tool is removing the stigma surrounding sexual practices. He explained this in an interview.

“We can’t tell people not to have sex, but we can equip them with tools, a bit like what happened with COVID. When people couldn’t take it anymore, they looked for ways to reduce the risks: certain positions, using hand sanitizer, wearing masks. Now it shouldn’t be any different. I think the State should support and encourage the destigmatization of our practices and the tools that emerge from organizations. Otherwise, we’ll continue with the same narrative of ‘well, it happens to us, but not only to us,’ and repeating that is returning to silence. It’s important to say yes, this is happening to us, these are our practices, and what do we do? Perhaps encourage informed control of them without sanitizing them.”

In this regard, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued some recommendations for safe sex .

“If it doesn’t affect the entire population, the State doesn’t act.”

Ahedo adds that there are three levels of prevention. The first involves actions to avoid infection; the second focuses on knowledge and diagnosis in early stages to access treatment, avoid complications and contagion; this includes vaccines and information, two resources that the Mexican State is not promoting.

The Mexican government has been slow to disseminate specific information about monkeypox to the general public. Unlike COVID-19, monkeypox is not discussed daily on official government channels. So far, the limited information disseminated consists of two epidemiological advisories, a guide for the technical management of the disease, social media content, and a website . There is no public awareness campaign about it.

Activists are demanding that there also be stigma-free information campaigns aimed at men who have sex with men and that reach out to meeting places.

“The Ministry of Health in Mexico does not provide information about monkeypox and does not reach out to people in places where it is common, such as saunas, nightclubs, or the Zona Rosa. Those of us who do this work are organizations, and Clínica Condesa is the only health facility that has undertaken this task. It seems that if it doesn't affect the entire population, the State doesn't act,” Pinzón denounces.

In that same vein, Ahedo adds that “prevention is also institutional; it requires public policies and emergency actions. Often, communities assume that prevention is their responsibility, and when they fail, they are left to pay the consequences. While self-care is key to protection, in the face of institutional neglect and abysmal management, we are sent out with a slingshot to face Goliath. The battle is not fair, and it is equally unfair that we are blamed for failing.”

The third level of prevention focuses on recovery from the illness, including physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation. Regarding this, Ahedo comments that “currently, monkeypox presents with mild symptoms that are rarely life-threatening, but the experience of living with it is not comparable in terms of psychological and social impact. We must seek safety measures because the stigma generates abandonment and rejection; we must free ourselves from guilt, acknowledge that we live with this virus and others, and protect ourselves from the increasingly acute social stigma.”

How to combat stigma?

As mentioned, the most affected population at this time are gay men, bisexual men, and men who have sex with men; making visible why they may be more vulnerable to the disease is one of the main demands that activists consider "to curb the stigma and improve prevention .

“It’s not about saying that just because we’re gay and living with HIV, that’s stigma. It’s about explaining why. And it’s because we can be immunocompromised, because we can have fewer than 200 CD4 cells (cells responsible for defending the body against infections and pathogens), because we can have a compromised immune system, because we can have an AIDS-defining illness, because we can have a sexually transmitted infection that complicates the treatment of monkeypox. By naming ourselves, by making this visible, we erase the stigma that thirty years ago damaged the community so much when the silence of governments led so many people to remain silent, to isolate themselves. Today we will not give up our silence. Silence kills,” Alaín Pinzón asserts.

“Gay men and men who have sex with men will be attacked whether or not there’s smallpox. That’s why I do believe that breaking the homophobic discourse means recognizing that we, at this moment, are a priority population. By not doing so, we run the risk of diverting attention and resources. Recognizing this gives meaning to the lessons we learned from the HIV epidemic,” commented Ricardo Baruch, PhD in public health and LGBTI rights, in an interview.

“When it wasn’t acknowledged that MSM (men who have sex with men) were among the most affected, it led to a lack of investment in information, prevention, care, and detection; which resulted in lost lives and opportunities for decades. But it’s also important to be mindful of the language used to emphasize that this isn’t something exclusive to our population. We can’t be complacent. Ultimately, prevention is everyone’s responsibility, regardless of our sexual orientation or gender,” Baruch explained.

“To avoid stigma, it’s crucial that the government first acknowledges this outbreak in our communities. Denying that it’s localized is terrible. I think it often happens that if health authorities or the government don’t say so, we don’t believe it. And I do believe that the government needs a concrete, not lukewarm, response that makes the specific groups affected visible. This doesn’t mean linking this disease to the general population. It means acknowledging that this is happening to us right now and that we need information, care, prevention tools, and vaccines,” added Ro Banda.

Photo: Georgina G. Álvarez

“Smallpox no, vaccines yes”

The WHO maintains that mass vaccination is not necessary. However, Rosamund Lewis, a UN specialist on this disease, does see post-exposure vaccination as necessary for at-risk groups. She believes that "it should be done based on the public health needs of each country; anyone who has been exposed to someone with monkeypox should be vaccinated first."

According to the specialist, there are currently just over 16 million doses of vaccines in storage. These are vaccines used to prevent human smallpox, as there are no specific versions to prevent monkeypox. However, of the three vaccines that are still being produced, their effectiveness and duration of protection against the current outbreak remain unknown. For this reason, she insists that “there is an urgent need for interregional collaboration, based on political will, to generate the evidence that supports the use of vaccines and antivirals for monkeypox, as well as to target them to the populations at highest risk of infection.”

In Canada, the United States, and at least 27 countries in the European Union, post-exposure and pre-exposure vaccines are being administered to at-risk populations.

Mexico has no stockpiles of smallpox vaccine that could be used in the current outbreak. Furthermore, health authorities insisted that, for the time being, “mass vaccination against this disease is neither required nor recommended.” They did not mention any at-risk groups.

According to Dr. Ricardo Baruch, a public health expert, “vaccination will be the strategy that allows us to be protected again, and therefore, to fully enjoy our sexuality, without fear of smallpox. The longer the government and institutions delay action in providing information, prevention, detection, and vaccination, the more difficult it will become to contain it, even if its spread is slow.”

And activists are demanding that the Mexican government purchase and administer vaccines, prioritizing the populations that are currently at greatest risk.

“We’re not asking the government if they want to vaccinate us. It’s a demand they have to fulfill for men who have sex with men, for people living with HIV who also have rights, who are also citizens, who also pay taxes. We shouldn’t have to demand it from this government that calls itself so open and progressive. And if they don’t comply, we’re going to continue protesting,” emphasizes Alaín Pinzón.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.