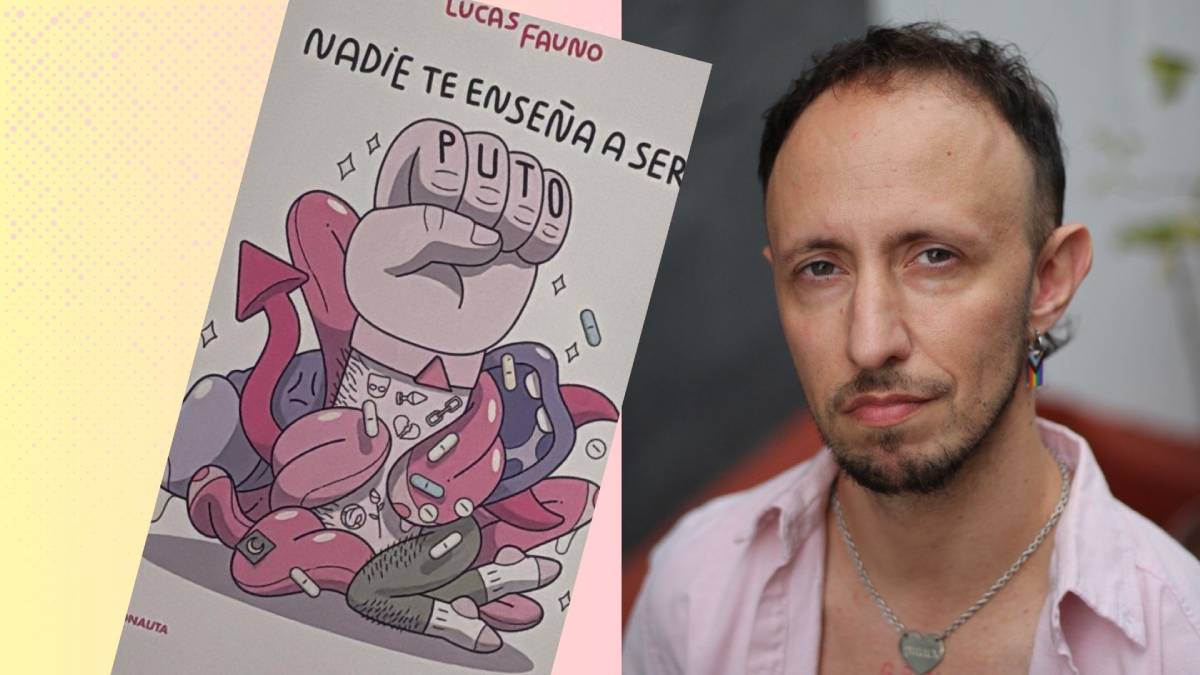

Femimutancia: “It's important to be able to start telling our stories from where we are.”

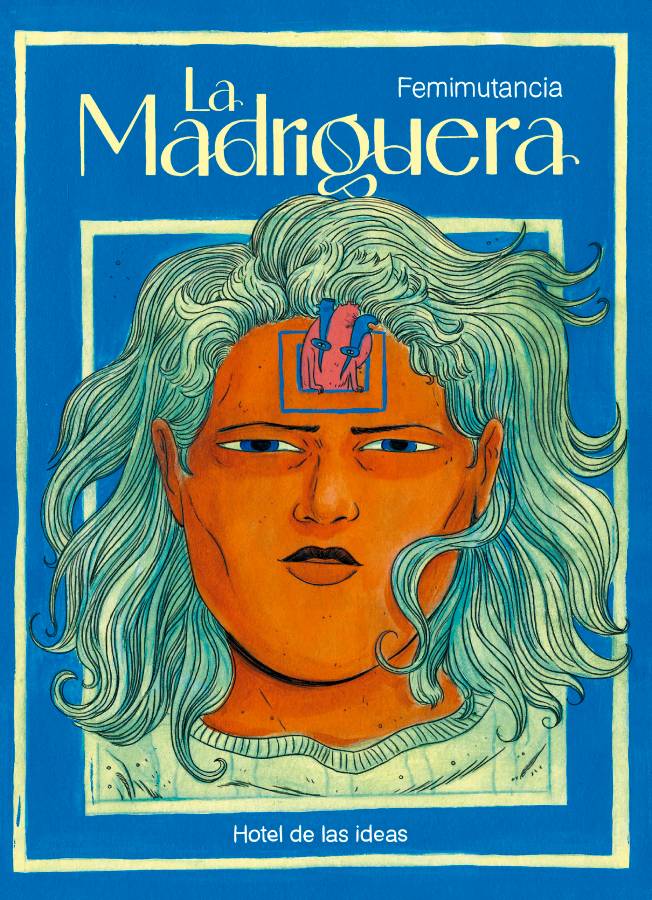

Her latest graphic novel, “The Burrow,” won the 2020 Proa Foundation Writing Incentive Award. Completed in just one year, this display of somewhat grotesque and fascinating illustrations explores her bond with her mother.

Share

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina. The name itself indicates it: what defines the work of Femimutancia , also known as Jules, is change, whether in their own identity or in their relationships. With four books and a fanzine published, their work, heavily influenced by autobiographical elements, seeks to re-evaluate the relationships we maintain in our lives.

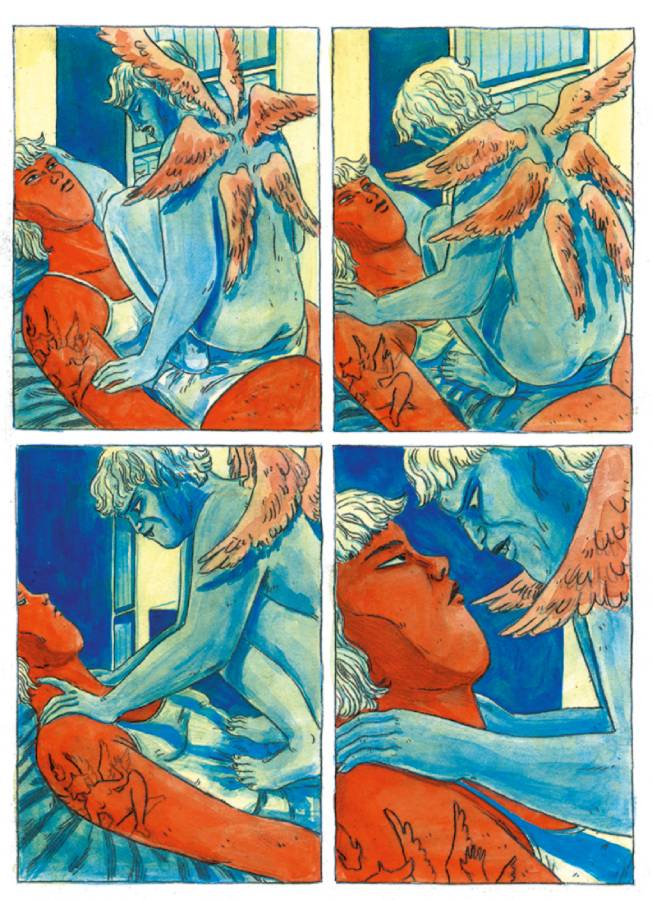

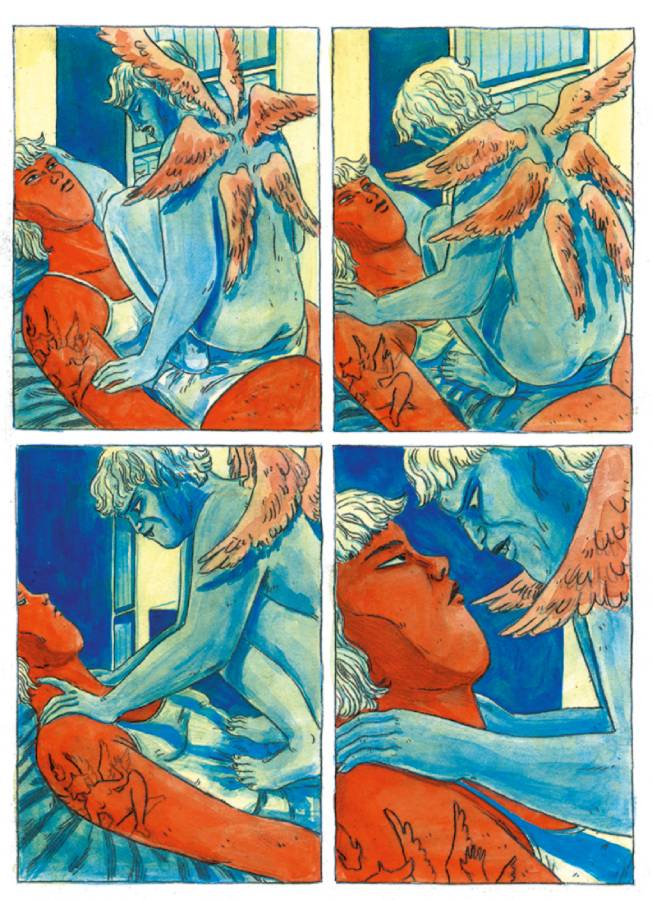

It also allows her, as she tells Presentes , “to transform the current trauma into something else, and to transform myself in that interim.” However, her style is distinctive and unmistakable, a hallmark of consistent work. With detailed, yet somewhat monstrous, illustrations, Femimutancia walks the fine line between fascinating and unsettling in every panel. This, combined with the clear influence of film and animation that permeates her work, makes reading her graphic novels like watching a movie and being unable to tear your eyes away from the screen.

– How did the idea for “The Burrow” come about?

The idea arose from the PROA competition that was launched in October 2020. Participants had to submit a book project on any topic, but it absolutely had to include the theme of the pandemic. I had been thinking that I wanted to write a kind of autofiction about my relationship with my mother, and I decided to take advantage of the competition and, since we were at it, use the pandemic as a narrative device.

-The pandemic is present but it's not the story, it's more the context. How did you think about it in that sense?

I thought of it that way, and also a bit like the first stage when the pandemic first started, when nobody really knew anything. There wasn't much information, or maybe there was too much, but nothing very precise. So at the beginning, I experienced it thinking that maybe the world would end in a week, and I tried to capture that feeling. I used that as a way to question reality and the particular situation of the character who has to come to terms with certain aspects of his relationship with his mother. At the same time, that relationship can be transferred to other people, not necessarily to the mother.

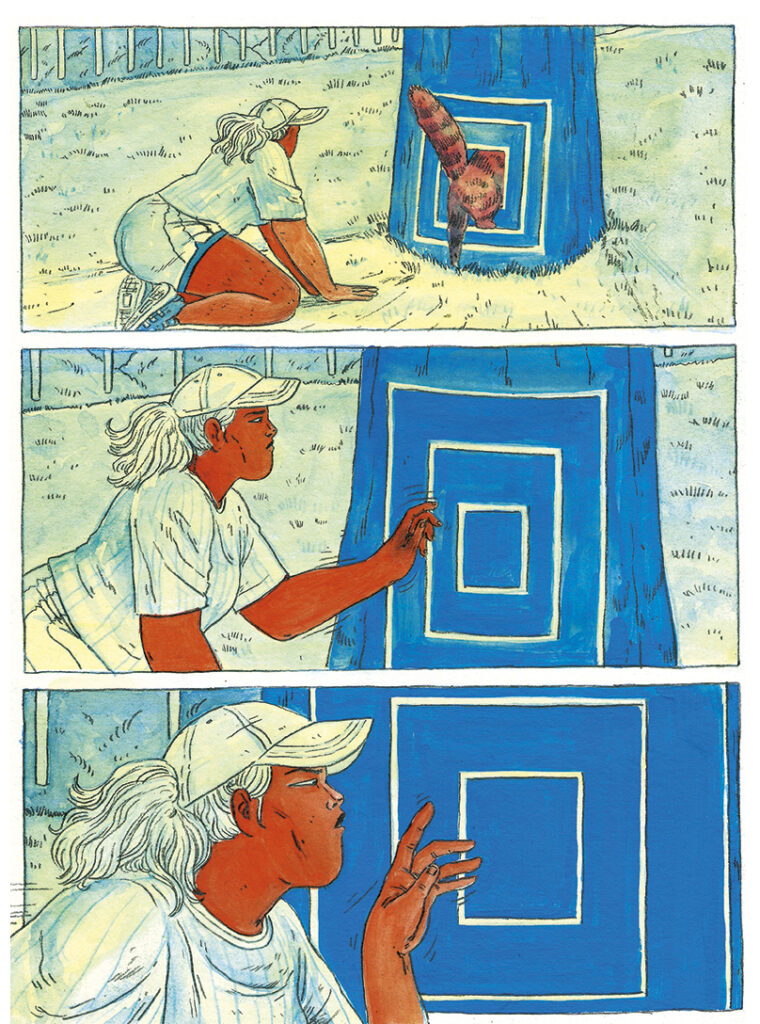

-At the beginning of the book, the character goes through a kind of portal. How did you come up with that image?

"I think it stems a bit from the fiction we create when we don't want to confront something. In my first book, Alien , the character is more solitary, and in the end, he implies that he goes to another dimension. So I took that idea a bit, the classic scenario of wanting to escape from something when life is overwhelming you, and you think you'd go to another country on the other side of the world, but in reality, no matter how far you go, those problems will still be there. You're not going to change. So what I wanted to convey with that portal, using the pandemic as an excuse, is that it doesn't matter if you're in reality or in another dimension, you're still the same person. It depends on how you deal with those kinds of situations; your mind is always the same."

-I found the use of music very interesting, how the character sings while riding his bike. It gives a soundtrack to a type of narrative that doesn't have one.

-Absolutely. It's kind of like that, trying to give another dimension to certain situations that happen to me, like when I'm riding my bike or when I start walking and I automatically need to listen to music. That transports me to other places too, so the idea was a bit like that, of another dimension.

-Throughout the book there's a very cinematic quality to the shots that are constantly moving, as if you were placing the camera in different locations. But the final conversation with the mother is frozen in a single image. Why?

I wasn't quite sure how I was going to handle that part so it wouldn't be boring. I already knew what the final conversation would be like, but I didn't know what the character would be doing on the terrace. I was traveling in Colombia and we were staying in a house with peeling walls. I went up to the terrace to take pictures of myself talking on the phone to get references for the sunlight. When I saw the peeling walls, I said, "This is it; it's like the character is shedding those layers." I also found it visually very interesting; it's in motion, but also static.

-Do you think that being openly non-binary and making art is a form of activism in itself?

I think it's important to be able to start telling our stories from our own perspective. That makes other people interested too. For example, I'm non-binary now, but for a long time I identified as a woman, and suddenly the comics where I found female characters were conceived and drawn by mostly heterosexual cisgender men. So when I read those comics, I didn't identify with those characters, because it was a story of one identity being told by another. I do feel there's greater visibility, but I'm not really sure how much of that is true. It sounds very Buenos Aires-centric to say that things are different nowadays because as soon as you move a little away from this city, I don't know how much things have actually changed.

– How would you define your style? What emotions do you seek to evoke?

-I want to wake up in a way that's a little uncomfortable, that has some nostalgia but also some refuge at the same time.

We are Present

We are committed to a type of journalism that delves deeply into the realm of the world and offers in-depth research, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related Notes

We Are Present

This and other stories don't usually make the media's attention. Together, we can make them known.