Violence and discrimination are the main debts that Latin American states owe to the LGBT community.

On the day against lesbophobia, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia, Presentes spoke with three activists about the importance of the date and the situation of the LGBT community.

Share

GUADALAJARA, Mexico. May 17th is commemorated worldwide as the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia . The date aims to draw attention to the violence, discrimination, and exclusion experienced by LGBTI+ people around the world.

In Latin America, there has been significant progress in recognizing the rights of these populations. However, states still have outstanding obligations to ensure that LGBTI+ people can live a life free from violence and exclusion.

Eighteen years after the commemoration of this day, at Presentes we ask ourselves: what does this date mean for activism in the region? What issues remain unresolved? What strategies are being activated to confront violence?

To answer these questions, Presentes spoke with Siobhan Guerrero , a Mexican researcher and philosopher of science; Nahil Zerón, a human rights defender and member of the Honduran organization Cattrachas ; Maldita Vaina , an artist and DJ from the Dominican Republic; and Roland Álvarez, a sociologist and archivist of queer, butch, transvestite, and trans memory from Peru.

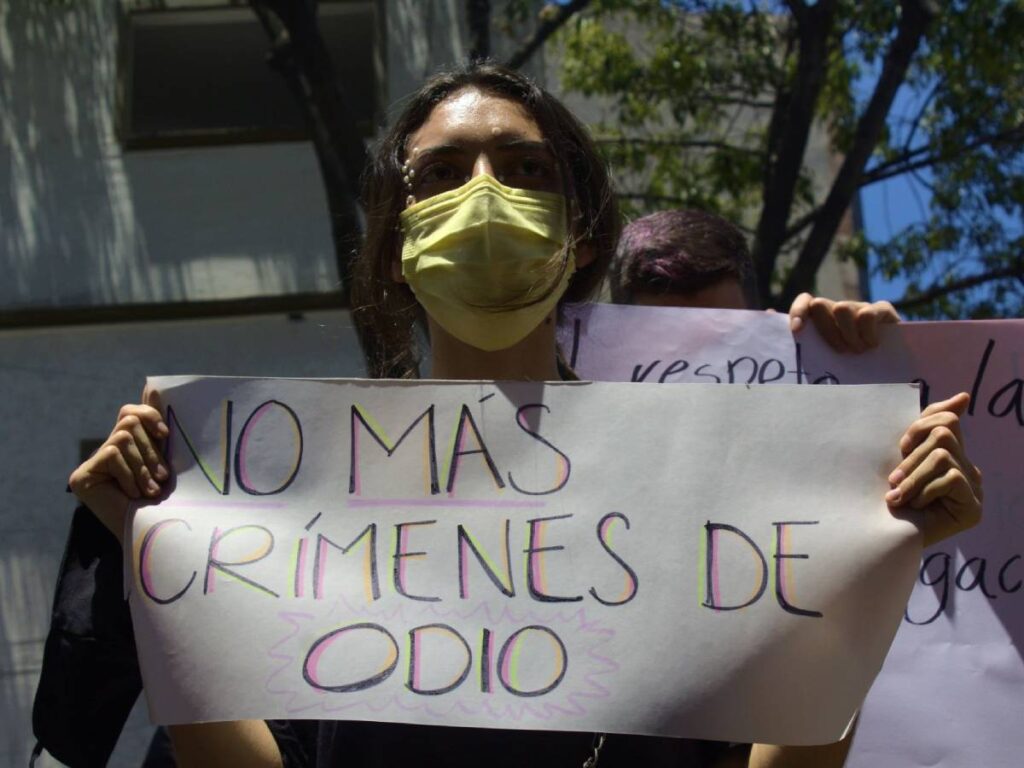

“Hate crimes are just the tip of the iceberg”

In Latin America and around the world, hate crimes are the most visible form of violence against LGBT+ people. But it is important to remember that discrimination, marginalization, and violence occur with varying degrees of intensity and are present in people's daily lives.

In this regard, Mexican philosopher Siobhan Guerrero emphasizes that “hate crimes are just the tip of the iceberg of a society that has other mechanisms of violence, including discrimination in employment, education, access to health, migration processes and access to justice.”

Furthermore, she notes that Mexico presents a paradoxical situation, where on the one hand there are governments, leaders, and media outlets that are “more sensitive” to the LGBTI struggle. “Sometimes, unfortunately, it only amounts to a series of gestures that don't necessarily translate into affirmative action policies, or into a society with mechanisms to combat violence,” the researcher points out.

Roland Álvarez warns that in Peru, the feeling of being merely "gestures" from the State also prevails. "On days like these, we may exist for the Peruvian State, but then it abandons us, and LGBTQ+ people don't live on gestures alone."

He adds, “This day is important for us to draw attention to the serious discrimination we face, the increasing hate crimes , and above all, the inaction of the Peruvian state, which refuses to acknowledge our existence. Peru is like an island amidst the progress of other countries. Here, our rights are not recognized; it's difficult to be gay, butch, transvestite, or transgender. And although some initiatives have emerged from government ministries, they are insufficient because they are weak in the face of a conservative Congress that rejects our proposed laws.”

May 17th, a mark for Latin America

In the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras), the situation is not so different. According to the Human Rights Watch report, " I Live Every Day in Fear," the lack of state protection, the presence of conservative and anti-rights groups in positions of power, and the violence perpetrated by gang members mean that LGBTI+ people in these countries do not have their human rights guaranteed.

In conversation with Nahil Zerón, a member of Cattrachas, she emphasizes that this May 17th “significantly marks all of Latin America” after the decision of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to declare the Honduran State responsible for the murder of Vicky Hernández .

She adds that it involves “not only making visible the lethal violence against LGBTI people, but also the discrimination and the continuum of violence they have experienced before being murdered. On days like this, we ask ourselves, how can we prevent this violence? And it is a very difficult question to answer when the violence is structural and systematic, dictated by state institutions, by the state itself, and replicated socially.”

In the Dominican Republic, violence, discrimination, and lack of protection for the human rights of LGBTI people also prevail. In fact, in June of last year, Congress removed sexual orientation as an aggravating factor in crimes such as homicide, torture, discrimination, and sexual violence from the Penal Code.

In response, Dominican artist and DJ Maldita Vaina explained to Presentes that the day against LGBTphobia is fundamental in that country to "raise their voices".

“International dates like this open up the possibility of raising our voices, creating spaces, and feeling welcomed. And in the Dominican context, that is very important because our history is one of censorship. Of not raising our voices because we have the Bible in the middle of the flag and above our heads, 500 years of a tremendously racist rule of law that has led to hate speech against dissidents and LGBT people.”

“To mitigate violence, we need to connect regionally.”

During the conversations with Siobhan Guerrero, Nahil Zerón, Roland Alvarez and Maldita Vaina, they agreed that "to mitigate violence we have to connect regionally the problems, the struggles and strategies."

Furthermore, they agree that there are forms of violence and situations that are not very visible, not only on the part of the State, but also for LGBTI+ activists and people.

“If 15 years ago people felt that the entire agenda revolved around same-sex marriage, today it is clear that this is not the case. There are problems that urgently need to be addressed,” says Siobhan Guerrero.

The outstanding issues they observe are: the lack of comprehensive sex education in educational spaces at all levels; the recognition of non-binary identities ; migration processes; the lack of training in health spaces; the end of non-consensual genital surgeries on intersex people ; impunity in hate crimes; revictimization in justice systems; people deprived of their liberty; violence against trans women over 35 years of age; and the attention and funding of specific shelters for people experiencing homelessness, older adults , and people on the move.

“Strategies to heal and strengthen our lives”

Regarding the list of pending issues, Roland Álvarez emphasizes that there are ways to strengthen the lives of LGBT people outside of legislative spaces.

“We, gay men, transvestites, and butch women, are creative and we develop strategies to heal from this violence and strengthen our lives. I think that's fundamental and something we need to keep in mind to strengthen the Peruvian LGBTI community fabric. We have a repository of knowledge, of intersubjectivities to recognize and understand each other, because we also have milestones to celebrate, to remember, and to confront those painful processes we go through when we face violence, indifference, and discrimination from the State and society,” the sociologist comments.

Along the same lines, Siobhan Guerrero shares that LGBTI+ people have also engaged in practices of care and knowledge. She says that this was “very revealing” for her after reading Hil Malatino’s Trans Care

“LGBTI people have not only built care networks but have also built specific knowledge of what it means to support people who come from contexts of pathologization. And I emphasize knowledge, because Hil Malatino mentions that there is a risk that the State will want to expropriate that knowledge, without recognizing that it is generated within the communities themselves.”

Furthermore, regarding knowledge creation, Nahil Zerón adds that it is “essential” to recognize the work of observatories that record violence against LGBT+ people. This is not only to acknowledge that states have a responsibility to collect this information, but also because these observatories help preserve historical memory.

“Those of us who do this work create a record of LGBTI identities not only by recounting their deaths but also their lives. This has allowed us to specialize in creating analyses of the contexts; in documenting who kills our comrades; in understanding the messages sent through these acts of violence. It also allows us to ask questions: Who has access to firearms? Because most LGBTI deaths involve firearms. What happens in a context of organized crime, and how is this affecting LGBTI people? And with these analyses, we also consider how to advance the prevention of violence against LGBTI people,” Zerón adds.

The collective task of overcoming fear

For DJ Maldita Vaina, one strategy she is beginning to see in the Dominican Republic is "the loss of fear," the recognition of the maroon identity, and the taking of spaces.

“We are clinging to our Maroon roots, to our way of existing in the country, and that helps us imagine and generate organization, spaces, points of support. That's something that moves me because we're starting to let go of fear, I'm starting to feel, along with my people, a sense of security that I can be a lesbian in the street. So when you start not hiding, when you start making your presence known, that becomes resistance, and I think that's important in our country right now, that strategy is there. The transformation also exists far from the power of Congress because the influence of the Catholic Church is too great to overthrow right now.”

Finally, philosopher Siobhan Guerrero argues that another strategy is the creation of public opinion, especially in a global context where it seems that progress in human rights could be lost.

“We must never forget that shaping public opinion involves transforming society’s perspective on an issue. It’s necessary to reach large audiences and foster a culture of respect, inclusion, and empathy. Some say that the law helps with this. But if you only achieve respect because it’s in the law or from a punitive standpoint, then it’s much easier to reverse progress. When respect stems from fear of punishment, there’s never a true process of humanizing the other person.”

And she concludes by saying: “If we only talk about prejudices, we can overlook the fact that there are indeed political emotions working against the LGBTI community because it has been discriminated against not only through discourse, but also through emotions. We are associated with disgust, whether through serophobia, homophobia, or the idea that LGBTI people are excremental, and that has an emotional component. And that is precisely what makes combating discrimination so difficult because it is not merely a matter of beliefs, it is also a matter of emotions. If I arrive with a lot of statistics, laws, and information, that doesn't necessarily transform or dismantle the disgust and contempt. That is dismantled in other ways, such as shaping public opinion, which I believe can employ more empathetic approaches to humanize LGBTI people.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.