The U'wa people of Colombia continue their fight against oil companies

Women are the pillars of the historic struggle that the indigenous people are waging in defense of their territory.

Share

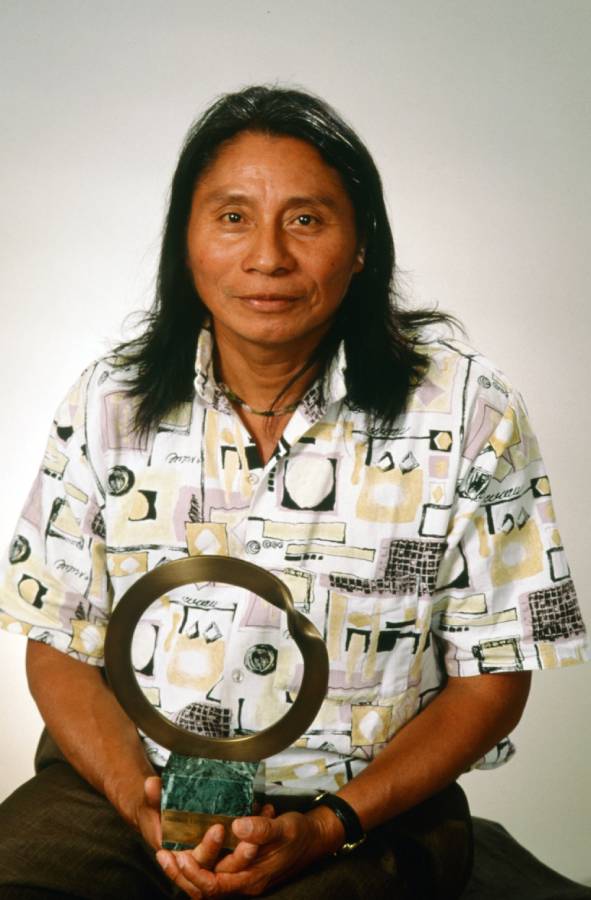

Daris María Cristancho, an indigenous U'wa woman from Boyacá, Colombia, was already a mother of five at the age of 28, and she was responsible for coordinating the mobilizations of her people in 2000 against the State and Occidental Petroleum Corp (Oxy), eager to extract oil from their ancestral territory.

It's a memory that lives on in her. The future of her descendants and all of humanity depends on the struggle and demands for the well-being of the land and water.

She and her U'wa brothers believe that the industrial practice of exploiting oil has nothing to do with development, "it is a wound that sickens Pachamama," says Daris.

Photo: Daris María Cristancho.

From a very young age he understood the meaning of Mother Earth, as U'wa has had a close relationship with her, cultivated her, benefited from her fertility, transported her and also witnessed her transformation and deterioration.

The U'wa people are distributed in 17 communities or councils in the departments of Boyacá, Norte de Santander, Santander, Arauca and Casanare, according to information provided by Daris María and contained in the characterization of the indigenous peoples of Colombia made by the Ministry of Culture .

According to data from the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) , the total extension of its territory is 352,422 hectares: 115,323 in Arauca, 220,275 in Boyacá and the Santanderes, and 16,824 in Casanare.

The descendants of the U'wa are estimated at 10,649, according to the 2018 DANE Population Census . The Association of Traditional Authorities and Councils of the U'wa (Asou'wa) estimates that as of March 2022, its members number 12,560. In Boyacá, 7,152 are registered, according to the Safeguarding Plan, and 55 percent are women.

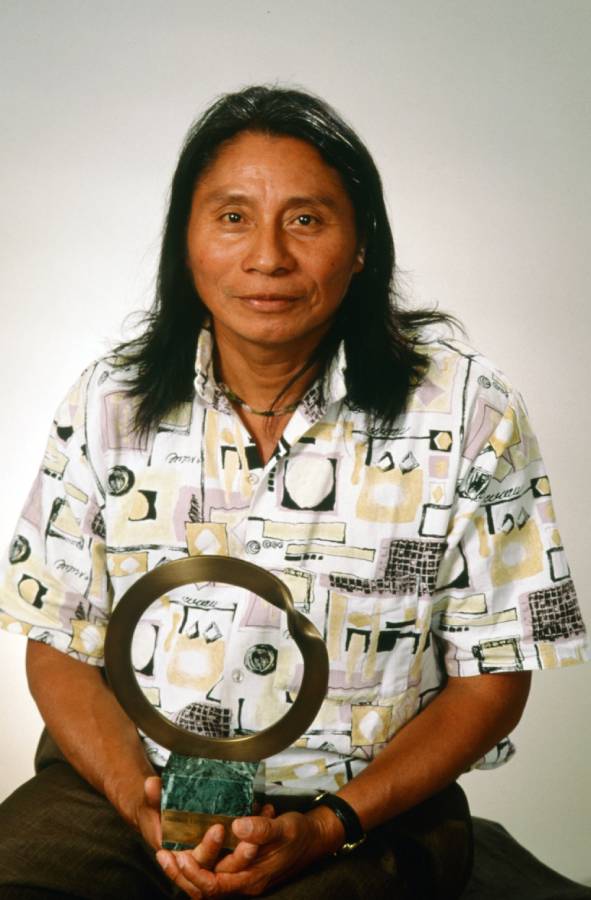

Photo: Julio Roberto Guatibonza.

In this same region, the U'wa have historically been located in the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, their spiritual space, which together with the lake known as Bekana, are considered the center of the world, as highlighted in a document from the population directorate of the Ministry of Culture of Colombia .

It also describes the distribution of several lagoons considered of great importance to the U'wa because in those places are the origins of their ancestors, "when the deities gave birth to a man and a woman from each lagoon."

The great leader

Daris María is a leader and spokesperson for the communities of Bachira and Salina, located in the municipalities of Güicán (Boyacá) and La Salina (Casanare), respectively, and collaborates as a cultural advisor for Asou'wa. She graduated as a teacher from the María Inmaculada Normal School in Arauca, earned a degree in Social Sciences from the Universidad Libre, and specialized in Environmental Management and Conservation at the Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga.

He currently works as a teacher at the Pablo Sexto School in Cubará, a municipality in the far northeast of Boyacá bordering Arauca, Santander and Norte de Santander, and the state of Apure, in Venezuela.

Today, at 50, she recalls what her participation and that of other women meant in the fight against the multinational oil company and the government. She remembers the actions undertaken since 1995, “it was a time to defend our territory and natural resources,” and that conviction led the U'wa people to raise their voices demanding respect for their ancestral lands.

Their presence during this period of heightened visibility of their community's demands was motivated by Berito Kuwaru'wa, one of the most remembered leaders for the simplicity and forcefulness of his arguments. Berito was the one who led them to undertake this process of resistance; "I learned from him, walking alongside him," says Daris María.

For the men and women who are part of this community and for those who voluntarily joined the challenge of confronting Oxy, including environmentalists from the United States and Europe, Berito is one of the main references in the struggle of indigenous peoples in Latin America against extractive projects.

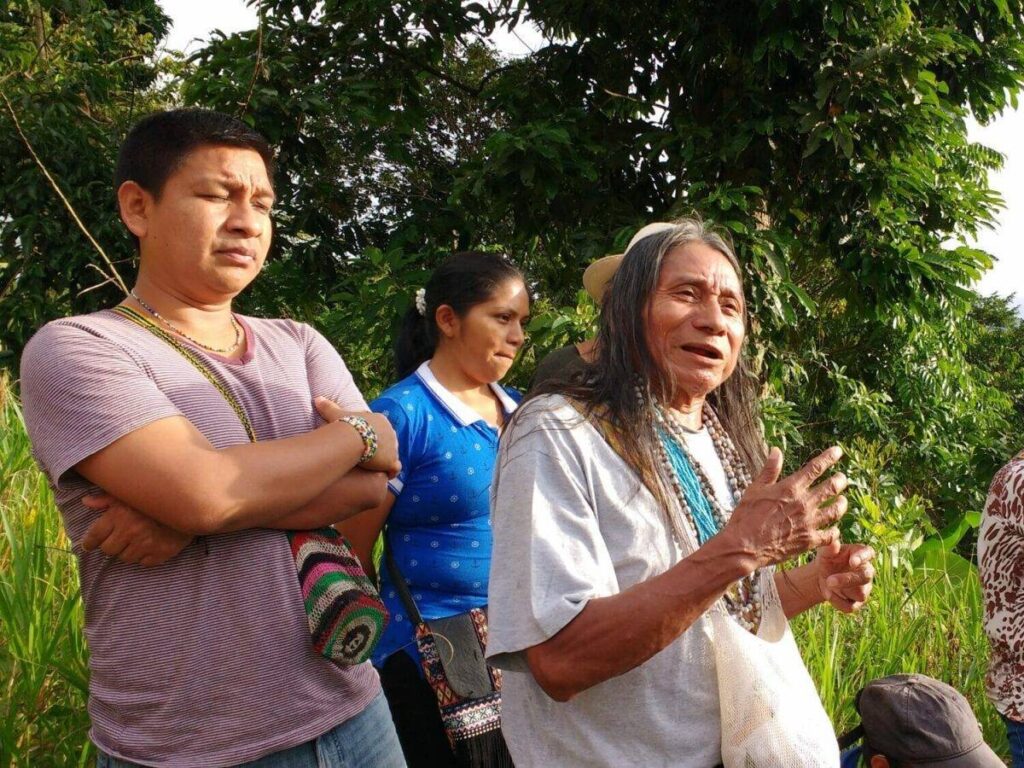

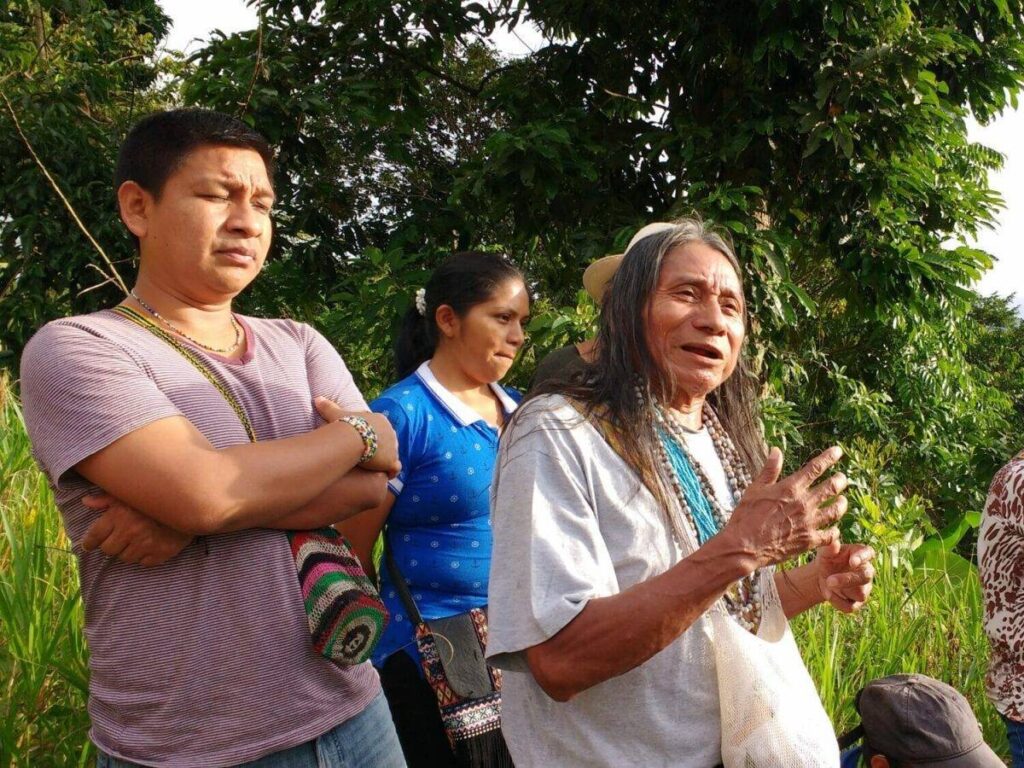

Photo: Julio Roberto Guatibonza.

Two fighters for a great cause

Berito, along with Daris María and other men and women from the 17 councils that make up Asou'wa, led the delegation that traveled to Peru and Ecuador in 2000, to the United States and Europe between 2000 and 2010, and to Canada in 2006, with the purpose of asking for support to face the harassment of the multinational and the Colombian government in search of subsoil resources.

The exposure of this conflict in global media coverage made public the claim of a native Andean people who asked for respect for nature, for their culture, for their vocation and for the sacred condition of the lands inherited from their ancestors; however, it did not prevent the government from granting Occidental Petroleum a license on February 3, 1995 to carry out seismic studies in the Samoré block , as documented by the NGO Earth Rights International (ERI).

The struggle of Berito Kuwaru'wa, the U'wa women, and their entire people was recognized in 1998 with the Goldman Prize , an award that honors the achievements and leadership of grassroots environmental activists from around the world.

Photo: goldmanprize.org

A year later, on March 3, 1999, three American citizens who were collaborating with the U'wa in the creation of schools to protect the local language and culture "were kidnapped and murdered by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People's Army (FARC-EP)," as recorded by the organization Earthrights International in a report on the demands of this indigenous group.

Terry Freitas, 24; Lahe'enae Gay, 39; and Ingrid Washinawatok, 41, had accompanied Berito on his trip to the United States to demand that Oxy abandon its interest in exploiting the lands of his people.

The persistence of the traditional authorities led to the Colombian government establishing the United U'wa Reserve in Boyacá on August 6, 1999, with an area of 220,775 hectares *; however, in this decision, an adjacent area was reserved to facilitate the presence of drills, machinery, and operators.

Photo: earthrights.org

The milestone in the fight against the oil companies

In 2006, the Ministry of the Interior gave Ecopetrol the green light to begin seismic work in the Sirirí and Catleya blocks, and currently the Gibraltar gas pipeline operates there, located in the Cedeño sector, a border area of the municipalities of Toledo (Norte de Santander) and Cubará (Boyacá), adjacent to the line that delimits the indigenous reserve.

In 2016, the U'wa people occupied this gas plant to demand that the government fulfill the commitments agreed upon in 2014, including the complete cleanup of their reservation. After several days of intercultural dialogue, the Indigenous guard agreed to withdraw peacefully while awaiting the fulfillment of their demands. This is recounted in a documentary produced by the Kinorama audiovisual collective in 2017.

Daris María also recalled another incident that occurred on the Santa Rita and Bella Vista farms, near the Gibraltar 1 well, during which military units, backed by helicopters, forcibly evicted members of the community guard. That day, several of her companions were tied up and then taken to a military base. This incident reaffirmed her conviction to continue fighting for her land, for her children, for water, and for life.

Today's struggles

Water is precisely one of the strongest arguments for persisting in their efforts. Their most recent claim concerns the protection of Zizuma, the U'wa Tunebo name for the highest peak of the El Cocuy snow-capped mountain in Boyacá, and more generally for the high mountains that dominate their ancestral territory. From there flows the water that sustains them and thousands of other inhabitants of regions such as Santander, Norte de Santander, Casanare, and Arauca.

For decades they have asked that the snow-capped mountain be part of the reserve, they have criticized the predatory practices of tourism and the lack of control of the entities in charge, especially the Ministry of Environment responsible for administering the El Cocuy National Natural Park.

In a meeting with the government on July 27, 2016, to discuss the status of the agreements, Berito, in a calm tone, uttered a phrase that his brothers still remember. “We are playing with nature and its creators. For our younger (non-Indigenous) brothers and sisters, both national and international, it seems that everything we look at on this planet is a business, but what will we take care of tomorrow when Mother Earth is sick?” He was heard saying this in a video published in February 2017. (Minute 12:54)

Traditional authorities continue to demand that their requests be fulfilled and maintain a lawsuit filed in 1997 before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS) to denounce the State of Colombia for not properly carrying out prior consultations within the framework of the oil project.

In a background report by the Commission, dated September 28, 2019 **, it determined that the State “violated their rights to collective property, to consultation and free, prior and informed consent (including violations of the right to access information and political rights), the cultural rights of the U'wa nation and their right to judicial protection and judicial guarantees.”

The report included the explanations of the state delegates. They asserted that they had implemented all measures within their reach, “relying on the coordination of the entities involved and the constant participation of the highest national and international authorities, with the aim of protecting the rights of the U'wa community, addressing their demands, and guaranteeing spaces for intercultural dialogue that allow for the peaceful resolution of the conflicts that arise.”

Regarding the use and enjoyment of collective property, the State argued, as stated in the IACHR's merits report, "that it is not an absolute right and can be limited, as long as the State remains the legitimate owner of subsoil resources."

In response to the U'wa people's complaints about alleged shortcomings in the prior consultation process, "the State maintained that it is recognized in the Colombian legal system and that it does not entail the right of indigenous and tribal peoples to veto legislative and administrative measures that affect them, but rather it is an opportunity for States to consider and assess their positions on projects, so the authorities always retain the power to make a final decision on the project's implementation."

Daris María reiterated that these demands remain in effect, and that very little of what was agreed upon, especially regarding the full titling of the reserve, has been fulfilled—"barely 30 or 40 percent." From her home in Cubará, she described what she called government deceptions and referred to the promise made by Juan Mayr, Minister of the Environment between 1998 and 2002, during the administration of former President Andrés Pastrana Arango.

Mayr assured them that their protection would be respected; however, according to their complaint, the delimitation of the protection left out a significant portion of land where crude oil extraction was later authorized.

For this reason they remain on alert and are preparing for when the time comes to testify before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

Photo: Germán García Barrera.

The U'wa Lawsuit

Laura Posada Correa, a lawyer for the NGO Earth Rights International (ERI) , an organization that supports the case against the Colombian State before the IACHR, cited the Inter-American Commission's 2019 report, which upheld the U'wa people's claims regarding the violation of their rights, particularly those related to the transgression of their cultural and social integrity and respect for their autonomy, the imposition of extractive projects, and the non-recognition of their ancestral presence and territorial control in the area where the Sierra Nevada de El Cocuy is located.

Juliana Bravo Valencia, director of the Amazon program at ERI, added that, given the evidence of non-compliance by the Colombian State, the case was referred to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the competent entity to issue or not a judicial ruling on international responsibility based on the analysis of the evidence provided.

She is confident that the Court will soon summon the U'wa, the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), the José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers Collective (CAJAR), and Earth Rights International to present their arguments and supporting evidence.

Security alerts

This situation is compounded by public order issues related to the internal armed conflict in Colombia.

Between 2018 and 2019, the Ombudsman's Office issued three early warnings about the risk to which several indigenous communities, including the U'wa, are exposed due to the actions of illegal armed groups such as the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the dissidents of the former FARC guerrilla.

Specifically, Early Warning No. 075 of 2018 documents the existence of an “imminent risk to which the communities of the U´wa people who inhabit the Chaparral Barronegro reserve, located in the jurisdiction of the municipalities of Sácama, Hato Corozal and Támara, in the department of Casanare, are exposed.”

The report made by the Ombudsman's Office details that the constant patrolling by the ELN violates the right to territorial integrity of the U'wa people, and impacts the exercise of their jurisdiction and self-government.

“This territory is strategic for the armed group’s purposes, facilitating the movement of combatants, weapons, supplies, and the smuggling of livestock and gasoline through corridors connecting the foothills and the savanna… and allowing them to evade law enforcement,” the alert states. Adding to this threat is the forced recruitment of children and adolescents.

Regarding the presence of FARC dissidents, concentrated in the 28th front, the Ombudsman's Office considers an additional danger given their intention to exercise territorial control and recover areas of former influence from which they obtain resources for their financing.

The Ombudsman's Office asked the Ministry of the Interior and the public force for urgent measures to prevent and protect this population, and urged this ministry and the National Protection Unit to structure in a concerted manner individual and collective security measures based on the strengthening, training and equipping of the Indigenous Guard of the Chaparral-Barronegro reservation.

In its most recent follow-up report on Early Warning 075 of 2018 , the Ombudsman's Office considers that the risk continues, and insists on the urgency to protect the civilian population and indigenous leaders who are threatened by the ELN and FARC dissidents.

U'wa woman, defender of life

Since the 1990s, the daughters of Sira, the supreme deity of the U'wa people, have played important roles in community management and coordination. Daris was one of those who, from a very young age, became involved in social and educational activities aimed at strengthening the essence of this people, teaching new generations the language and traditions that characterize them.

With their dedication and enthusiasm, they have joined the main council that brings together local Indigenous authorities in Asou'wa and have represented them before national government entities. They have assumed their role as spokespeople and have received academic training to speak on behalf of their Indigenous brothers and sisters. In this way, they have overcome their own shyness and the lingering machismo still evident in Indigenous communities.

Aura Tegría Cristancho is part of this new generation. She has a law degree and has served as mayor of Cubará since 2020. Her mother, Daris María, has been an example of leadership and perseverance. She taught her to demand her rights, to seek opportunities for participation, and to make informed decisions as an U'wa woman.

These Indigenous women leaders face many challenges. Daris recalls her trips abroad and what it meant to speak in public before packed auditoriums or before the microphones and cameras of international television. “The fear wasn’t doing it itself; what worried me was the risk of returning to the country after denouncing the abuses. We know that in Colombia, those who speak out are silenced.”

Despite the danger, the U'wa woman trusts Sira, "he will always be with us to defend our position and to help us wisely resolve and win the process of struggle and resistance and defense of Mother Earth."

Claudia Cobaría Bócota is also part of this group of spokespeople that has emerged in recent years. Her indigenous name is 'Abacha', which means 'Morning Dew'. Until a few months ago, she was the secretary of the Association of Traditional Authorities and Councils of the U'wa (Asou'wa), and her advancement within the organization is a recognition by the people and their authorities of the leading role of women in household dynamics, agriculture, raising children, and defending their territory.

'Abacha' recalls that her vocation for leadership arose when she was just a child, seeing Daris Maria and her companions on their national and international journey to tell the world about the situation of their people.

Together with other U'was women and men, they have witnessed the back-and-forth with the national government, the pronouncements for and against issued by the courts, the permits granted by the Ministry of Environment for the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons in their ancestral territories, the environmental alterations caused by soil drilling and gas burning, and the judicial decisions that ordered the Colombian State to grant title to the united reserve.

In her experience as a member of the community's management teams, Claudia refers to the participation of women in the educational processes of new generations.

The U'wa, based on their ancestral knowledge, educate their children and young people to make proper use of the land, to treat it in a balanced way, without damaging or depleting it according to the laws of their worldview, and in this task women play a fundamental role.

'Abacha' defines her mission as paramount, that of her mother, that of her grandmothers, that of all the women of this indigenous collective, "woman is mother and is the essence of teaching," she says, in direct reference to the daily experiences at home and the instruction given daily to those who follow in their footsteps in the defense of the territory.

Photo: Julio Roberto Guatibonza.

Principles of life

Sira, the creator god, the supreme being, the spiritual guide of the U'wa people, left a legacy for his community, a series of principles that govern their relationship with life, water, soil and mountains; a set of laws to live in harmony with nature and the animals with whom men and women share the territory that was inherited from them, the lands of their ancestors, which they cultivate, which they walk, which hold their remains when it is time to return to the essence, as recorded in the community's Life Plan and in various academic documents .

Sira is a permanent reference among those who proudly identify themselves as U'was, that "intelligent people who know how to speak ," and it is not to boast, that is the Spanish translation of the name that identifies this ancient community belonging to the Chibcha linguistic family, and which according to its own description "was one of the largest in the Andean zone of Colombia at the time of the conquest," as described in the Safeguard Plan U'wa Casanare People .

The Safeguarding Plan makes a heartfelt recognition of the territory as a living being with its own spirit that has a function of harmony and balance, a being that, however, is seen by Western thought as a source of wealth and resources.

In this declaration, their elders lament that the riowa, the white man, the non-indigenous person, represented by the State and multinational corporations, views their ancestral lands, inhabited for thousands of years, as barren and unproductive lands, intending to exploit them according to their extractive logic. “The actions of the riowa on the land lead to an imbalance in the spiritual life of the U'wa and, consequently, to their disappearance from the land.” This is described in the document U'was: Vision and Testament , published in Polis, a Latin American journal of Open Edition Journals.

It is a collective cry for the healing of the planet, which is currently suffering from the effects of climate change, low soil productivity, and diseases that disrupt the integrity of men, mountains, rivers, plants, and animals.

The wisdom bequeathed by their elders and transmitted from generation to generation has allowed them to have "their own ordering of their territory according to their law of origin, their sacred spaces and their way of interacting with the environment for their daily life," according to the U'wa Life Plan.

Photo: Julio Roberto Guatibonza.

The impacts are evident

Claudia Cobaría speaks with pride of her community's leadership in defending Sira's legacy, laments the state's persistence in extracting "the blood of the earth," and then expresses her concern about the evident damage to the territory, the deterioration of the soil, the pollution and the decrease in water sources, the instability of the land, and the landslides.

In their inventory of impacts, the U'wa mention the effects of flares—devices for burning gases at an oil facility—used for gas flaring. Their werhjayas, wise elders or traditional healers, refer to this industrial practice as the burning of the earth's spirit and the resulting imbalance of the air, responsible for respiratory and skin diseases that were nonexistent before the arrival of oil and the presence of settlers eager to exploit nature's resources.

Unturo Tegría, former president of Asou'wa, reaffirms this problem. He emphasizes that oil is the lifeblood of Mother Earth, that its extraction causes disharmony and imbalance, and that it endangers the survival of his culture, his people, and many other living beings.

Unturo also describes the changes in rainfall patterns. He is concerned about the uncertainty surrounding winter and summer seasons and what this means for food security.

“When it’s supposed to be dry season, it’s raining, and when it’s supposed to be winter, there are droughts. Crops hardly grow anymore; the plants that provide food don’t last. Before, you could plant a seedling and there was no need to plant it again, and you’d have food forever. That’s how the family survived. Now you have to clear the land and plant new crops. That’s a consequence of poor land management.”

These alterations in the dynamics of planting, harvesting, rainfall, and dry days are an expression of the imbalance that Berito, the elders, and the traditional authorities have been observing for several decades. It is what scientists have called climate change.

An official position

The Boyacá Governor's Office explained its perspective on the struggles of the U'wa people. Sara Vega, Chief of Staff, spoke on their behalf. She stated that since 2017 they have been participating in the Intercultural Dialogue Table established to discuss differences of opinion between the indigenous people and the national government on issues such as the regularization of their reservation, the presence of oil installations near it, and the protection of the Sierra Nevada de El Cocuy or Zizuma.

Their participation in this dialogue was prompted by the decision of the Association of Traditional Authorities and Councils of the U'wa (Asou'wa) to block access to El Cocuy National Natural Park for tour operators and visitors. The Indigenous people blamed tourism for the deterioration of this protected area, which is essential for the environmental balance of the territory and the subsistence of their own communities and others located in this region of the eastern mountain range.

Sara Vega explained that one of the commitments made by the Governor's Office, in conjunction with National Natural Parks, was to commission a study on the socio-environmental impacts in the El Cocuy páramo. This study was conducted by the Pedagogical and Technological University of Colombia (UPTC) between 2018 and 2019, and the site visits were accompanied by representatives from Asouwa.

“We have also acted as guarantors and facilitators in the U'wa people's petition to the Ministry of the Interior regarding the restitution and legalization of their reservation lands, and in road-related matters such as the completion of the Sovereignty road works, on the La Lejía – Saravena route, in which the Governor's Office contributed as a co-financer,” Sara Vega stated.

This road allows communication between the departments of Norte de Santander, Boyacá and Arauca, especially a route used by natives to travel to and from the center of the country.

Regarding the dispute over the presence of oil and gas extraction facilities near the border of her lands, Sara stated that the Boyacá government maintains a neutral position on the matter. She affirmed that they have informed the parties involved in the conflict of their willingness to act as a guarantor for negotiations on this issue.

Regarding the complaint filed by the U'wa against the Colombian State before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), he stated that to date there has been no official request to the Governor's Office from that international tribunal.

Damage to the land and the pandemic

The U'wa say that the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic was not something new; the elders had warned about it several years ago, "four to be exact," recalls Claudia Cobaría.

They had warned that the white men or the Riowa were challenging Mother Earth with their interest in exploiting natural resources, which would bring serious effects to their communities and that global punishment would be recorded.

Indigenous spiritual leaders instructed their people not to hide from the challenge of nature, but to accept it with courage and respect, and gave them the order to dedicate themselves to growing food to maintain reserves and have a positive mindset.

Claudia explains the instruction this way: “If you have acted right, you have nothing to worry about. This disease will not attack the Uwa people because we have done what is right. The disease will come, but here we have the air, the winds, and nature that protect us. Dedicate yourselves to your cultural practices, and if the disease comes to you, remain calm. If you are afraid of it, the disease will strike you. If you eat well and begin to respect the laws of God and nature, everything will be alright.”

The message served as inspiration to Sira's children who, during the pandemic, renewed their respect for the law of origin and for the principles of balance, peace and harmony in their territory, even despite the extractive harassment.

*Document: New Paths for Conflict Resolution. Latin American Experiences. Case of the Uw'a people. Page 97.

**Document: Fund Report of the U'wa Indigenous People and its members. Pages 29 and 30.

Note. This story is part of the journalistic series Paths for Pachamama: Andean Communities in Reexistence!, and was produced in a co-creation exercise with indigenous and non-indigenous journalists and communicators from the Tejiendo Historias Network (Rede Tecendo Histórias), under the editorial coordination of the independent media outlet Agenda Propia .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.