The strength of women against the double pandemic in the Sierra de Zongolica

From a small orange house in Zongolica, women who speak native languages, community leaders, and survivors are fighting against gender violence after several femicides in the area.

Share

The 'women's fortress' is a small orange house in Zongolica run by women who help others break free from violence. The 'women's fortress' is also what inheritors of traditional medicine, speakers of indigenous languages, community leaders, and survivors found in the fight against gender-based violence after several femicides in their area.

This is what Emilia Tepole Xalamihua found to become an official interpreter from Nahuatl to Spanish so that women could file their complaints, in a predominantly indigenous area where the agencies lack people to do that work.

, Nahuatl woman and Nahuatl-Spanish interpreter.

This is what Juana Cano Tepole, daughter of a traditional healer, discovered when she devised a way to provide sex education to girls and boys in the region. Despite the stigma surrounding it, and to recover from the loss of close relatives to the pandemic, she returned to her team to help many other women.

They, along with about a dozen other women, have operated this space for 12 years. Officially, it's called the Indigenous Women's House (although their civil association is called Ichikahvaslistli Siahuame, or the Women's Fortress, the name they identify with more), with a brief mandatory break due to the Covid-19 pandemic. They had to return quickly from that break; the cases of violence against women kept coming.

The facility is officially one of the Indigenous Women's Houses, a government initiative in Mexico with centers distributed throughout the country to combat violence against women. Although they are government-run spaces, the resources allocated to them are insufficient. It is the women themselves who organize to ensure their survival.

Its director, Karina Cano, points out that sometimes women even go to the homes of those who run CAMI to ask for help, and that the resources they receive are only enough to cover a scholarship for half a year. The rest is purely volunteer work. All of this takes place in one of the most important mountain ranges in the state of Veracruz, encompassing nearly eight municipalities.

A home for everyone

Emilia Tepole Xalamihua

Emilia wanted to study, but her family only allowed her to do so up to the second grade. She also wanted to learn Nahuatl, the language of her father, her mother, and the people of the region, but they didn't teach her that either.

Word by word, whether to sell products at her dad's store or to understand what her grandmother was trying to tell her, she fulfilled one of her dreams: to learn her mother tongue.

He fulfilled his second dream many years later, when he left his hometown to work, married in the nearest city, and embarked on a quest to obtain his education. He finally finished high school at the age of 45.

Twelve years ago, she sold snacks in the heart of Zongolica and was a liaison for social programs. So when she received a letter inviting her to participate in forums about the situation of indigenous women in the area, she wasn't surprised.

The official letter was sent by the then-Commission for Indigenous Peoples (now the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples) after two women from the region were murdered. Ernestina Ascencio, a 73-year-old Nahua woman, was allegedly sexually assaulted and murdered by members of the National Army. However, the government later claimed she died of chronic gastritis. The other woman was activist Adelaida Amayo. She was missing for several days, and her body was found bearing signs of torture.

The two cases ignited unrest in the Sierra de Zongolica. Organized groups rose up. The army was barred from entering the Soledad de Atzompa area (Ernestina Ascencio's municipality). The women raised their voices.

The government's response was to invite the women they considered leaders to forums about their situation. Training followed, and before they knew it, they were looking for a house to work with other women.

Gender violence can be fought

“I kept asking myself: what is the Women’s Center going to do? What are we going to do? Well, we have to support women who are experiencing violence. Although I thought they wouldn’t believe us. We don’t have that kind of academic background, but it can be done, and I realized it’s not difficult. It can be done with everything we’ve learned,” says Emilia, who is in charge of the support area, where they provide counseling to women.

She leads the legal counseling and support services provided before the State Attorney General's Office. Her colleagues follow up on each of the cases they have handled. Periodically, they visit their homes (nestled in the mountains) to check on their current situation and see if they require further assistance.

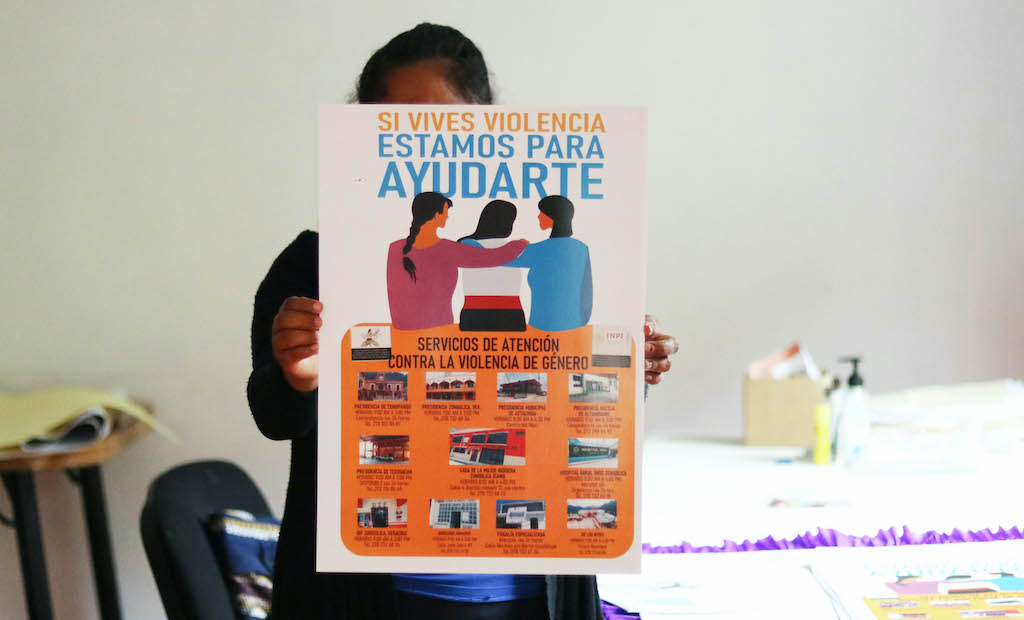

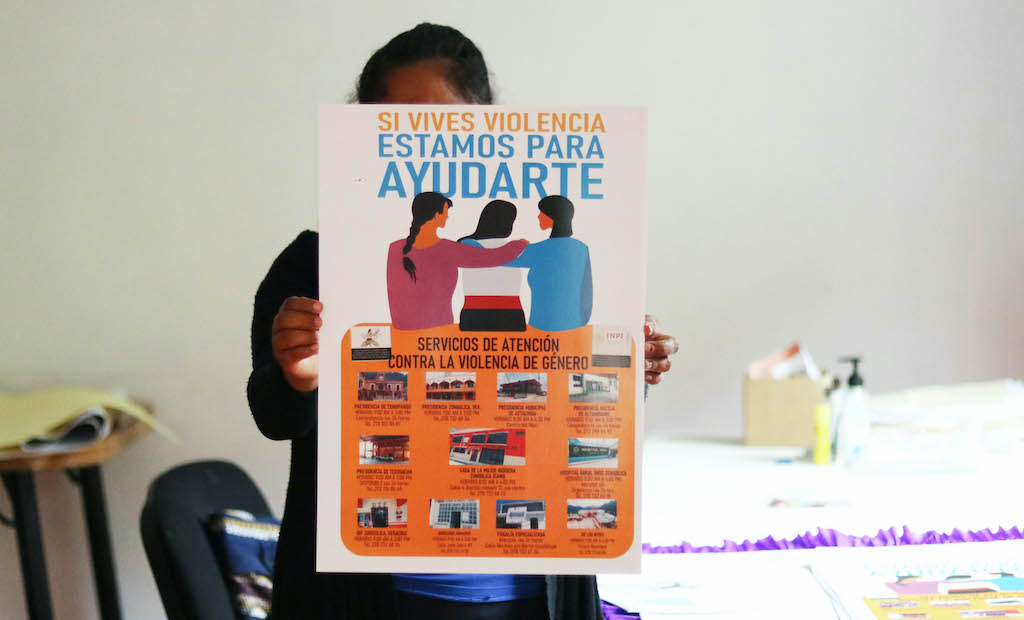

They offer courses and workshops to help women identify the types of violence they are experiencing. They give talks on comprehensive sex education for children through adulthood. And they produce a wide range of content, such as plays and radio programs, to raise awareness.

The house also houses a space for psychologists sent by government programs and who attend to women who come seeking help.

Violence against indigenous women in Veracruz

According to the University Observatory of Violence Against Women, which compiles data from local media, between January and June of this year, 5 femicides, 4 homicides, 21 disappearances, and 30 attacks against women living in indigenous municipalities in the state of Veracruz were recorded. For the entire state, the number of femicides between January and July was 42, and the number of intentional homicides was 45, according to the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System.

For the right to be heard

Emilia smiles as she proudly recounts her work, explaining that she is now an official interpreter of her native language and that women who come to CAMI, even without speaking Spanish, can file their complaint and seek the justice they deserve.

She even recalls a case of rape of a minor that she accompanied to the State Attorney General's Office. But the word "rape" doesn't exist in Nahuatl.

“He treated me badly” was the literal translation of what she was saying, but the public official could not record it exactly as written in the minutes because it meant nothing to the Spanish speaker.

It was through his ingenuity, the words used to describe the genitals, and a lot of patience that he was able to obtain the complete description to put it in an investigation file that could lead to finding the person responsible.

“I told my mom and my siblings that I sign the folders, and they ask me which folders. And I say, well, where I'm going to interpret, and what does my brother say to me? He says with a rude word, 'You're awesome because you sign the folders.' And I tell him yes, that I have to sign where I helped to translate the Nahuatl language into Spanish,” she says about the pride that her family now feels for the work she does.

But in fact, the language problem that Emilia faced is common for the members of CAMI, according to Cristina Juárez and Leonarda Xohiycale, who are in the community area that is in charge of giving courses and workshops in the communities so that women can detect violence.

Words that have become common in Spanish, such as femicide, sexting, or digital violence, do not exist for speakers of the Nahuatl language.

For women in those communities who only speak their native language, they must learn to describe events and provide translations that allow them to identify if they are experiencing them.

It is for things like this that their work is essential, and no pandemic will stop them from continuing to do it.

With their face masks ready, Cristina and Leonarda prepare their materials to go to the communities and explain the different forms of violence. They are already familiar with these areas; they were among the women CAMI helped a few years ago, and thanks to that, they escaped the violence they were experiencing. That's why they joined the group La Fortaleza de las Mujeres (The Women's Fortress); after overcoming violence themselves, they decided to help others.

Currently, 13 women take turns going to the house, as they cannot all be there at once to avoid overcrowding. Of the ten founders, one has passed away and another left for personal reasons, but others have joined, especially to reach the most remote communities.

To confront violence in their own lives

Juana Cano affirms that those who have joined are like Cristina and Leonarda, service users who receive training, empower themselves, and decide to help other women. She explains that the women at CAMI have had to confront the violence they experienced in their own homes, either directly or indirectly.

“We are very well known,” she says, after explaining that in the town where she lives (an hour from Zongolica), everyone knows that she is at the Indigenous Women's House and the same is true for the rest of her colleagues.

“So if any woman is going to say, ‘Well, if you want to give me advice on how to stop experiencing violence, why don’t you call your brother’s attention to it, or why don’t you help your sister who is in a violent situation,’ tell her, ‘You want to fix things on the outside, if you can’t fix them on the inside,’ then that was a part that we all worked on, and I personally worked on it,” she concludes.

She stood by her sister-in-law the day her brother beat her and was determined to see him imprisoned. She also helped her sister separate from her husband, and now she lives happily with her children. She established a strong sense of responsibility among her five brothers, three sisters, nieces, and other close friends and family, demonstrating that she knows their rights and will defend them. In doing so, she put an end to the violence against women in her family.

And the work didn't end there; at 41, she is single and plans to study nursing to continue in the field of medicine that she learned from her mother, a traditional doctor.

Facing both pandemics

When Juana remembers her mother, her heart swells with both pride and sadness: she passed away in April, and Juana couldn't say goodbye because she and her brother had Covid-19. That wasn't her only loss; her sister-in-law (who was like a sister to her) also died, and there was no farewell for her either.

She faced this crisis during months when she received no income, as CAMI's staff works on a volunteer basis (and when they do receive it, it's minimal, since it's only a stipend or scholarship). Adding to the financial burden were the costs of oxygen, funeral expenses, and other necessities. And because she was one of the first Covid-19 cases, people in the area shunned her family.

That's why she considered leaving her work at the House. But the day she stepped inside, she knew she had to return: her colleagues embraced her, gave her their support, and didn't leave her alone.

But Juana is not the only one who has already had the disease that has claimed thousands of lives in the world; there are now five members who have had it.

That's why, when you arrive at that small orange house, from the inside door they ask the reason for the visit and the first contact you have is with the gel and the sanitizer.

In any case, they say, there have been women who come to them and when they go to the prosecutor's office they realize that they have a fever, something they couldn't have known because they don't have money to even buy a thermometer.

At the height of the pandemic, they tried to close the shelter, but it didn't work. The women still needed help and went to people's homes to ask for it. Nothing stops the pandemic of gender-based violence.

Juana and Emilia agree that cases have increased, and the problem is even more acute because the municipal presidencies in the state of Veracruz will change in January. Currently, government agencies are closing out their administrations or transitioning to the new administration and ceasing to provide support.

The Municipal Institutes for Women or the DIF (National System for Integral Family Development) that normally served to guide women on the process of filing complaints, provide psychological support, or help to address health problems, are no longer functioning and cases are now going to the Indigenous Women's Center.

At that moment, its members spoke, gathered courage, and decided it was time to reopen, taking precautions and knowing that there were risks of getting sick.

But they, Emilia says, are not afraid. They trust that their strength will protect them, help them get through it even if they get sick, and they know how essential their work is.

And so they smile, all together, as they insist on being in the photo, in front of that space that the Fortress of Women has brought forward, theirs and that of all those who come to that small orange house.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.