Mothers of the mountain: Indigenous memories and knowledge for a good life

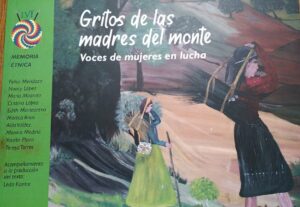

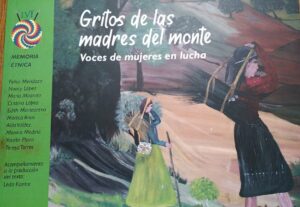

Based on an Ethnic Memory Workshop, the stories of “Cries of the Mothers of the Mountain, Voices of Women in Struggle” rescue ancestral knowledge and experiences of good living of women and trans people from seven indigenous peoples of the Salta Chaco.

Share

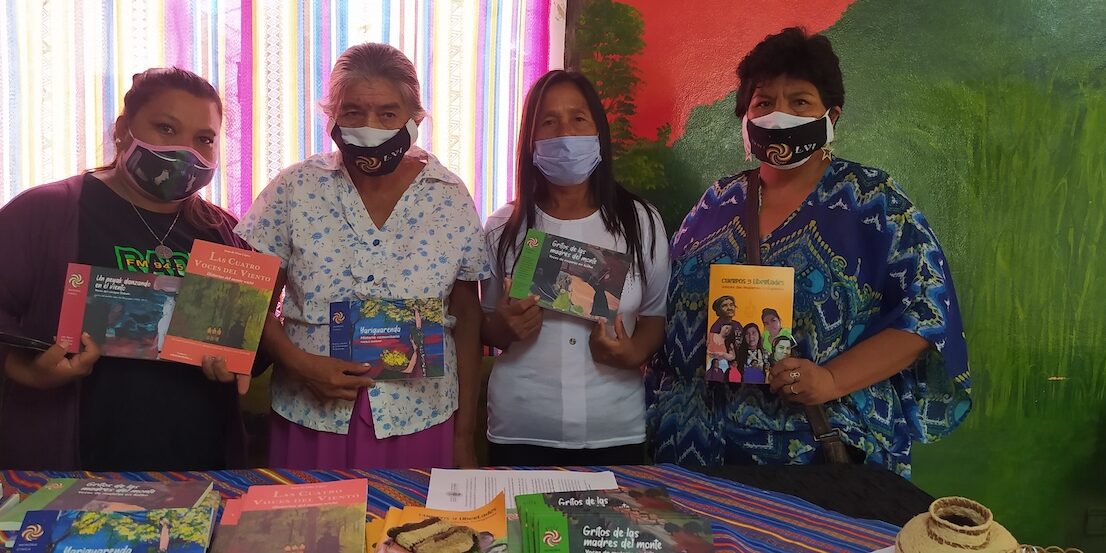

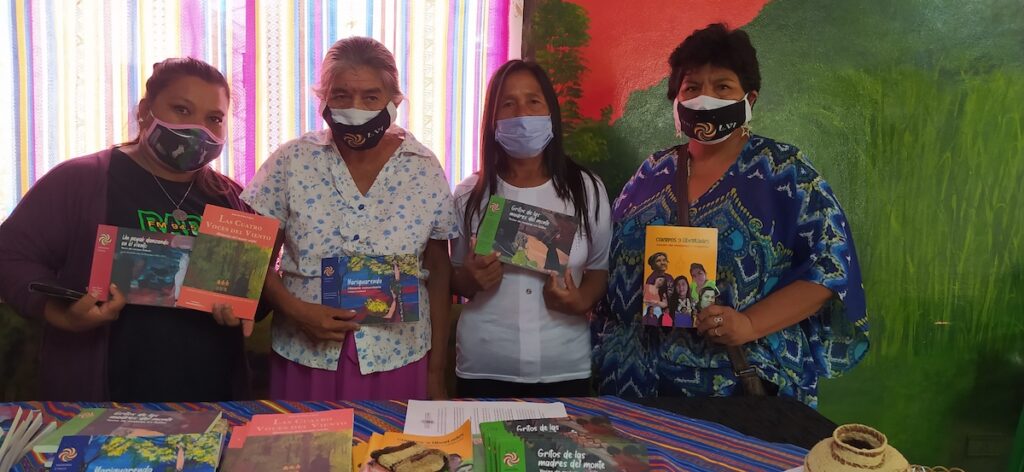

A group of Indigenous women meet to share experiences and stories, and to recover ancestral knowledge at the Ethnic Memory Workshop in the city of Tartagal, in the northern part of Salta province. The members of the Aretede organization and the community radio station La Voz Indígena The pause caused by the coronavirus pandemic opened a crucial process: to finish systematizing and publishing a series of four books and a booklet, with content based on their stories and narratives, the product of this Ethnic Memory Workshop.

One of the books is “ Cries of the Mothers of the Mountain, Voices of Women in Struggle ,” a work “written communally.” It brings together the experiences of women and trans people from seven Indigenous communities inhabiting the Chaco region of Salta province. They not only denounce the abuses in the area, but also emphasize the need to listen to what nature has to say through its guardian spirits and guardian beings. Nature, the earth, they say, is angry at the damage humanity has inflicted upon it, and that is why diseases like Covid-19 appear.

This is the third book published by Aretede (the formal organization of this group) and the community radio station La Voz Indígena . The authors are Felisa Mendoza, Nancy López, María Miranda, Cristina López, Edith Martearena, Mónica Arias, Mónica Medina, Aida Valdez, Yocelin Plaza, and Teresa Torres. They sought to tell the stories of their people and their profound connection with nature, the mountains, and their spirits, a connection essential for a good life.

“It talks about what life was like for the people in times when there was only land and forest, what life was like for the women, for the people,” “what societies and cultures were like, what it was like to go out in groups to gather and hunt,” says anthropologist Leda Kantor, who assisted in the production of this work. And it also talks about what came after. “When roads, towns, and cities began to be built. About the advance of the agricultural frontier, the establishment of oil companies, the beginning of extractivism”; about “the transformations in the lives of the people, the entire process of evicting the communities,” she explains to Presentes.

Leda is not just another anthropologist. Indigenous women recognize her as a "comrade" and part of their families. Twenty-five years ago, she first came to the banks of the Pilcomayo River, to Misión La Paz and Kilometer 1, almost 200 kilometers further northeast, in the Chaco region. Since then, she has been part of this group of women dedicated to preserving the memory of their people . And it was at her insistence that the Ethnic Memory Workshop was started, from which these materials emerged.

The book “Gritos…” was presented in Tartagal at a meeting conceived as an intercultural dialogue, which took place on March 12th, filled with emotion on both sides. Although the initial idea was to present it in the city of Salta and other provinces, and make it available for sale there, the pandemic put those plans on hold. Presentes spoke with her and some of the book's authors.

Although the book had been in development for at least three years, it was completed during the pandemic. Funding from a project of the Southern Women's Fund helped to finalize and edit it. And in that process, the book also incorporated a collective reflection on the pandemic. “Women see it as part of the damage that humanity has done and continues to do to the world, to nature. And that all of this is also part of the Earth's anger, of the need for a change in the extractive model that is so damaging to the planet,” says Kantor.

The book's second chapter recounts the arrival of extractive activities in the territory, but also the struggles of the local communities to resist them. It tells of how the native forest defends itself. “And that defense is also spiritual. From there, it unfolds as a series of stories about all the spirits that own the forests, the animals, and the fish.”

The women recount the situations they experience: deforestation, inexplicable accidents, and “the things that arise from the spiritual defense of the mountains themselves” when they are invaded without permission and without respect. This chapter, the third, ends with the story of “the mothers of the mountains” and of “all the feminine spirits that in some way make up nature and how they are safeguarding the world.” All the stories stem from reflections in the Memory Workshop, as well as from interviews they conducted with other older women in their communities, bearers of their experiences and knowledge.

Telling the story of the good life

In conversation with the authors, common ideas emerge, expressed in various ways. The importance of recovering the history of their peoples, with their sorrows and their joys. The conviction that wealth has nothing to do with private property; that well-being can only be achieved by respecting other living beings and is therefore impossible in an extractive system; that Indigenous peoples hold knowledge that is valuable for all humanity.

At 72, Felisa Mendoza is perhaps the oldest member of the collective that worked on the book. At the presentation, she explained that they created it to raise awareness of their communities, to share their childhood experiences. “We had the forest; we used to talk about 'good living,' which we no longer have. Good living means having the forest, the land, all the food the forest provides, the medicine, ” and “we no longer have all of that.” Everything is cleared “to plant soybeans. We are becoming increasingly impoverished of the things we once had. Before, we were rich, rich in everything. We had forests, we had crops, we had enough to live on. We had our rivers that flowed endlessly, where we could go without worry. But not anymore.”

“Screams…” contains “our history.” It speaks of the owner of the mountain, that spirit who cares for everything within it, a loving being always ready to help but capable of causing harm if nature is mistreated . The book is also an effort to ensure that this knowledge is not lost. “Books are very important so that this knowledge remains for our children,” so that “they know what the history of women was like in the past,” Felisa explained.

Guarani trans woman

Yocelin Plaza is 36 years old, a trans woman from the Guarani community of Misión La Loma (Tartagal). She loves playing soccer and is one of the participants in the Ethnic Memory Workshop. Nancy López, a long-time member of the Workshop, an Indigenous communicator, and a leader in the El Quebracho community of the Weenhayeck people, calls her “my companion, my sister.” She invited her to join when she saw in her the same suffering that any Indigenous woman experiences, the pain caused by discrimination. They embraced her, says Nancy, “she is a living being just like all of us.”

In her childhood, Yocelin alternated school with work and play. “We try to tell our story, to tell how happy we were, how in our childhood we would go to the fence, run through the woods, hunt with our parents. This book is based on everything we have lived through, told with our soul, with our heart,” says Yocelin. And she explains that “the owner of the woods is a person who protects us. When we enter, we ask permission to hunt, just as we ask permission to plant.”

My beautiful childhood

Mónica Medina, from the Weenhayeck El Quebracho Community, also has fond childhood memories. “When the forest was healthy and pristine, there was no deforestation, all of that.” “My childhood was beautiful. Before going out to gather carob with my grandmother, she would first talk to the sun.” If it was very hot, she would say to it (she says it in Qom): “ Nala', avi'imaqtq, qaica hntap naie, hinaectagueto naua hiua'alle, ñató ca hamap seroua'a ca hima' nache sacheguenaq”

“Sun, stay calm, don't get so hot today, I'm taking my granddaughter and grandson because I'm going to collect carob so I can get home and feed them.”.

All year round, they used to gather fruit from the forest. “The carob season ends, and then it’s time to harvest chañar fruit. When that’s over, we pick other fruits that are ready. Then there’s the last harvest, wild beans.” “That’s what we used to look for, but these days there’s nothing left. You look around and there’s only fields. Sometimes planes fly over to spray pesticides. I think we’re losing our culture; the children don’t know it anymore. When I brought a book home, I read it to them. They (his children) were sitting there, and they asked me lots of questions about what life was like, and I explained everything to them.”

Mónica also used to go out with her father to gather honey. “I know it was a very beautiful life that I lived with them.” “They knew how to provide us with food, because he was also a hunter.” Before, “he would talk to the forest too; they would say: hey, here I am, don’t be angry with me, I don’t come here to kill just like that, but I want to feed my children, my family, I only want to hunt what I need for this day, nothing more .

Now, however, “there are no more forests, there is such a scarcity of all that fruit. There are fields, soybean crops, fumigation, and through all this one begins to think about so many diseases that are unknown to us.”

Mónica says she recently experienced the power of the mountain spirit again. Her husband contracted Covid and was very ill. They refused to take him to the hospital, afraid of leaving him alone. She remembered her grandmother's words: "If something serious happens, go to the mountain," and her great-grandmother's teachings about the healing power of certain plants. She asked Nancy López to accompany her to the small patch of forest that remains in her community on National Route 86, surrounded by soybean farms.

“I asked for permission, I spoke: I know you are here, you exist, you are here, and now that I am suffering, I need your help, and I want you to show me the medicinal plants that grow in this forest .” And she walked along, smelling each plant, each with its own fragrance. And when it is medicinal, it has a scent that can be clearly perceived. She cut branches from each one, boiled them, and with that, she relieved her husband’s suffering. “I experienced that the owner of the forest exists,” and when you speak to him from the heart, he listens. That is why they defend that piece of forest, because “I know that its owner is there too.”

The grandmothers knew the healthy mountain

Among the major changes, besides deforestation and fumigation, Nancy López added "the roads." At 54, Nancy met the elders and learned their wisdom. The grandmothers knew which carob trees bore sweet fruit and which bore sour fruit.

“Today we're experiencing many unknown illnesses, for example, skin diseases we've never known about,” just as they didn't suffer from “headaches or stomach aches.” She recalls walking “barefoot through the woods,” never having accidents, “we never suffered like that” because “before entering the woods we asked permission, also before going to collect materials for our work.” Now, as older people, they continue to do so because “everything we see has an owner.” Now you have to be very careful when entering the woods. There are many soybean fields, and so they see “plants that are half-sick” because “they've already been sprayed, the agrochemicals that are killing us.”

That's why they also wrote this and other books: "so that many people know why the mountain is so important to us. The mountain is our life; that's why we've grown up healthy. Stop deforesting. We want a healthy mountain; we want the medicine , not the diseased medicine. We don't want those sick things anymore; we want things flourishing, with flowers that bring life. Many people don't know this, but we have the wisdom."

From when the mountain was an amusement park

Teresa Torres is 65 years old and one of the oldest in the group. From the Wichí community, she also lives beside Route 86, near Tartagal. Her memories are more than painful, but also more than happy, though it may seem contradictory. At some point, she recounts how they used to live happily, “peacefully, we slept well, we ate fruit, every morning we would playfully shoot, grabbing sticks and leaves like for dolls, and there were no worries.” She says the forest was “like an amusement park,” where they played climbing trees and swinging on swings. “There was no danger, no one told us to be careful, that they might catch us .” Today they live in fear, “when we have a daughter, it’s ‘don’t go, honey, there’s danger out there .’ Before, there was no danger, we ate everything from the forest, it was healthy, and we were healthy too.”

“Some people are ashamed of their history. We didn’t know what a mattress was; we slept on scraps of skin. We’d make a fire in the middle of the bed when it was cold, very peacefully.” They had no shoes or decent clothes. “It was very sad, but we were happy to be in that place.”

“Today I can’t look for chaguar, I can’t go out to look for a stick of firewood, because there isn’t any. Everything is cleared. There are soybeans, there are beans, the planes are spraying pesticides over our houses. And who respects us? They don’t respect us. We want the forest back, like it used to be. So we can walk and play, laugh and touch those fruits we used to touch, those fruits we used to eat: the chañar, the beans, the mistol.”

That happy life ended one day when they were kicked out, Teresa says. “They turned us back from where we were,” like those dogs that “no one would defend, that no one could say, ‘ Stop this, they’re people too.’ It wasn’t like that; instead, they chased us away, our belongings scattered about.” They told them, “Go ahead and shoot, because you can shoot, settle somewhere else because this place doesn’t belong to you, it belongs to us.” “Now we’re all scattered, a little here, a little there. We’re not together in one place anymore, because they don’t want us to be; they’re kicking us out.”

“I think if they kick us out of here again, I don’t know where we’ll go. I want to say enough is enough. That’s it. I want the forest back; perhaps in my final days, I’d like to see that forest again. I’m this woman who wants them to stop, to stop. And to stop spraying, and to leave the trees alone.”

Man has disrespected the world

Mónica Arias is 30 years old and also from Kilómetro 6, a large community where people from the Wichí, Chorote, and Qom communities live together. She is the daughter of a Wichí father and a Qom mother, Lidia Maraz, who was also a member of this group of women and has since passed away. Mónica is the great-granddaughter of Chief Taikolic, the legendary Qom leader who resisted the white invasion of the Pilcomayo territory for decades.

Like the other authors, she declares that nature has its owner and the forest has a spirit. She emphasizes the need to preserve it for future generations. She warns that deforestation affects the customs and culture of Indigenous communities. In addition to other, more visible harms, there is a farm's airstrip very close to Kilometer 6. "Every year (the plane) starts spraying pesticides for planting, and it harms us; we're right next door."

Mónica says that Covid-19 is related to “so much pollution.” It’s part of “the consequences” of what people do: “humanity has disrespected the world through deforestation and burning the forests.”

She recalls another book they published: “A Peyak Dancing in the Wind: Voices of Chief Taikolic,” which recounts the Qom people's resistance to the white invasion. That struggle, the great-granddaughter says, was waged with the help of the spirits. Every time there was a battle, the elders would gather and ask the spirits for help. That's how they defeated the enemy.

She believes that younger generations are losing this knowledge. “Perhaps to adapt to today’s world, to avoid feeling rejected.” Mónica heard from cousins who attend university and suffer what in the Western world is known by its English name, bullying . “That’s why many of us young people don’t have that opportunity. We often feel rejected as Indigenous people. I don’t blame them, but perhaps many young people who graduate from university practically forget they are Indigenous in order to be like them, to be accepted and not rejected as Indigenous people, to avoid feeling discriminated against above all else.”

That's why the book aims to teach about their ancestors, their culture, and the need "to respect the world, nature, and animals." Because it's necessary to return to that knowledge and for "our culture to be respected."

The birds don't know where to perch

“Now is the time to say enough to deforestation, we want the forest. Because the forest gives us life, it gives us health. Because that's where we find our medicinal remedies,” María Miranda emphasizes. She is the daughter of Felisa Mendoza, who convinced her to join the group, because “women also have rights.” “Today many are going to clear the land,” and the animals are lost, “the birds don't know where to perch because there are no trees,” she describes.

“We say enough, enough of deforestation, enough of suffering this pandemic, this disease we didn't know before and that is now in our midst. Our Mother Nature is angry with us, with all of us; this pandemic is happening all over the world. We say our Yanderu Tumpa (or Ñanderu Tupa, the creator) is angry. When we hear the rain, the wind, the destruction elsewhere, it is because our Yanderu Tumpa is angry with everything we are doing. We are not taking care of the forest. Through this book, we want our young people, our children, to know how our ancestors cared for this environment and that we continue to fight for it .”

María states that deforestation plunged Indigenous communities into poverty, although this concept has a different meaning than it does in the Western world. In Indigenous culture, wealth simply means having what is necessary for a good life, nothing more, nothing less.

In the case of María's community, which was affected by the urbanization of Tartagal, they can no longer plant crops. They also lack the forest to harvest their produce. "Before, we were rich, and now we are poor because they are destroying our forest."

Of riches and poverty

The first two books, “Moons, Tigers, and Eclipses” and “The Birds’ Announcement,” also emerged from the Ethnic Memory Workshop. They have now printed four more books, plus the booklet “Bodies and Freedoms.” And they are considering creating a fund to republish the books.

Leda requests that this note highlight the tireless work of the women in the Memory workshop group. “The presence of Felisa Mendoza, an incredible woman and fighter for memory, Lidia Maraz, Nancy López, María Miranda, Cristina López, Yocelin Plaza, who joined us recently, sharing her experiences as a trans Guarani woman, Aida Valdez, who recounted her memories of the struggle in the community against the various extractive processes that took place there; Mónica Arias, Edith Martearena, a group of extraordinary women.”

They've known each other for many years. “We're friends, we support each other, we're like family, and working with them is a source of pride and pleasure. I recognize them, their work, their history, and for dedicating themselves to the struggle and being the only organization in Tartagal that has sustained itself through so many years of daily struggle,” she says. This work of preserving memory is closely linked to Radio La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice). It's the space where all these voices are expressed and these memories are shared day after day.

Leda Kantor says this book “reflects a unique richness.” In it, the women also speak of the mother spirits of the mountain, spirits that teach. They recount that if one enters with a need and speaks with the owner of the mountain and with the mothers of the mountain, one experiences a wisdom that comes to end that affliction. And she emphasizes: that is why they propose an intercultural dialogue that shortens the distance that allows us to know the poverty of indigenous peoples but not their wealth.

To purchase the book, write to: fmcomunitarialavoz@gmail.com

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.