"We need transvestite-trans housing inclusion now!"

"Housing neglect is also a form of social transvesticide," writes Alma Fernández. She shares stories and urgent issues regarding access to housing for transvestites and trans people.

Share

A month after Argentina went into lockdown due to COVID-19, the National Tenants Federation (FIN) warned that six out of ten people (referring to cisgender people) would be unable to pay their rent in May 2020. The FIN also warned that if this figure were based solely on the trans community, it would be much higher and more alarming: nine out of ten transvestites and trans people would be unable to pay their rent in May 2020 due to the impact of the coronavirus . That is, 90 percent of the transvestites and trans people living in the City of Buenos Aires.

The amount the City provides to assist single people experiencing homelessness is 4,500 pesos, in a city where even the most basic rents cost between eight and twelve thousand pesos in any family-run hotel, sharing bathrooms and kitchens with other tenants. With 4,500 pesos, where would trans women rent? And to this we must add a proven fact: being trans makes everything more expensive. And although our dreams and rights are non-negotiable, sometimes I think that nobody cares about them.

A year passed, and in May 2021, the housing neglect faced by trans and travesti people remains unchanged. It seems that, from the perspective of inclusive and progressive laws, we continue to be pioneers in Argentina, although when it comes to putting them into practice, trans and travesti people are far from being equal in terms of rights.

Just as we call any hate crime aggravated by gender identity "travesticide," we call the historical (long-standing) abandonment of our identities by the State "social travesticide." Social isolation is a class privilege. And the quarantine is exacerbating this social travesticide, which is the lack of access to rights such as decent housing. Expelled from the formal labor market, during the pandemic, transvestites and trans people didn't have time to develop the habit of saving.

There won't be 15,000 pesos for us to get through this difficult time, unlike the support announced for other groups. Nor has there been any initiative or anyone in Buenos Aires asking, "Where are trans women going to rent?" Every night, many of us go out looking for work. At the beginning of the pandemic, a certain impatience among us made it difficult for some of us to clearly understand the proper use of face masks, or to learn how to convey that message of caution when we're working in dangerous areas.

Because: how many times will our bodies be the only tool we have to put food on the table or pay rent? Of all the demands and needs of our community, today I want to write about the need for housing. Beyond the centrality of this city, where housing assistance categorizes transvestites and trans people as indigent. With 4,500 pesos, no one will rent to you, but there's almost always a plan B that saves us. And so, the transvestites and trans people of the city arrive in the slums, and the slums embrace them. From there, we begin to realize how important it is to build networks; that's why our struggle is first and foremost a class struggle, until our luck—and the plague—changes.

What happens when you don't live in the richest city in the country? What happens when the only person you often have by your side is someone just like you, fighting side by side? How important it is to have allies and friends who support you and help you develop a plan to address your housing needs and move forward with building a home for trans women.

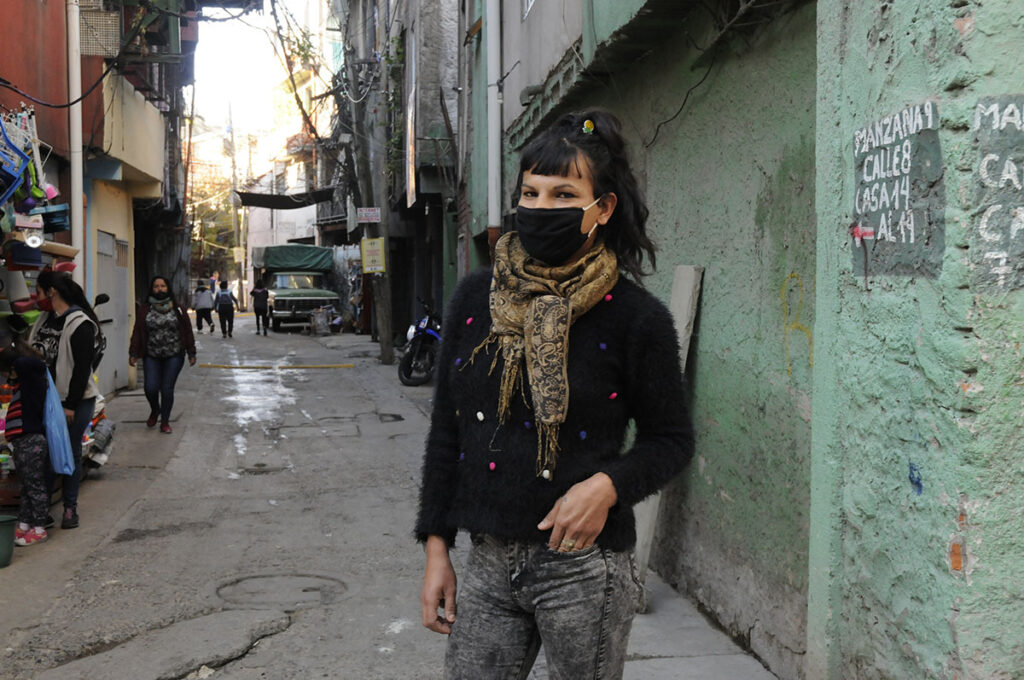

This is the case of Mía Gabriela Benítez from Chaco. With the help and organization of many friends, they formed a team, played the game, and won. Mía wanted the dream of owning her own home to extend beyond her own, so she decided to open a soup kitchen. The reward for so much effort is reflected in the love Mía puts into decorating her house and running the soup kitchen, which operates in the same place where she lives, with the idea of starting a productive unit for trans women and trans people in the province of Chaco.

Housing: a dream fulfilled in service to others

Mia is 28 years old and a trans woman from Barranqueras. She says, “ With a lot of effort, I managed to buy a piece of land. My partner at the time and I built a little house. I used to work as a prostitute on the street, and I managed to get out. Thanks to that, I was able to buy the land, and we made our love nest (let's call it that) .” Mia recounts that her partner started studying. “He was an abandoned boy who used to live on the streets.” She supported him so he could study. Time passed, he got his training, and today he's a bricklayer and electrician. “He also knows a lot about plumbing. And today it was my turn to get off the streets, thanks to God and the Virgin Mary, who put wonderful people in my path.”

She managed to get a kit of construction materials "to make a missing improvement to my house and finish it. I had the roofing sheets, I went to the Provincial Housing Institute and we managed to build two rooms with a bathroom and a porch where I can serve afternoon tea. As I continue to move forward, I help others to move forward too," she says, her voice filled with emotion.

Mia says she is grateful to those who helped her obtain the necessary resources for the soup kitchen where she works today (Wilson Morienaga, president of the Mocedad de Resistencia Foundation, provincial delegate Javier Zamudio, and Diego Arévalo from the Provincial Housing Institute). Although she is studying and working at the soup kitchen, “I don’t have any financial support or a stable job,” Mia says.

The transvestite trans body is a naturally social body, experiencing desperation and suffering to survive in a society that both desires and hides it. The transvestite trans body has learned that no one is saved alone. It has learned to embrace in order to stop feeling the coldness caused by the neglect of our social needs.

Alexia, a trans woman who became homeless in Mendoza

A couple of weeks ago, the case of Alexia Biancorroso went viral on Facebook and WhatsApp groups. In a viral video, she and her partner, Marcos, a person with a disability, denounced fraudulent practices by the Mendoza Provincial Housing Institute. In the same video, Alexia also denounced an arbitrary judge who discriminated against her and her partner, calling them transvestites and disabled, and accusing them of being evicted anyway for squatting.

In the video, Alexia says: “ I live in Godoy Cruz, Mendoza. I am a trans woman and a survivor; I lived through the dictatorship and its aftermath. I am married to Marcos Gastón Pari, a person with a physical disability.” She then shares how she became homeless. “It was because of a house that was given to me when Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was president, in 2007, through a housing recovery program. It had initially been assigned to a family that wasn't living there, but due to a family situation, it was given to me.” In 2011, Alexia's father suffered health problems. Her mother was 70 years old; she is now 80.

“The people from the Institute had assigned the house to my mother. Later they told us it was under a loan agreement. It was a lie, probably because they saw me as a trans woman. We live in the house, with my sisters and nephews. We paid the taxes, put up a gate, made repairs, and installed kitchen and bathroom fixtures. We had to adapt it for my disabled parents, so we built a ramp.”

In 2013, Alexia married Marcos and began working in the province's senior citizens department. "One day, my mother and I said, 'Let's see when we have to pay the fee, because we weren't receiving the bills. They told us we had to wait and not worry.'" The story is long and complicated. Along the way, there was a change in administration. They continued to demand the allocation. Until they were told: it was canceled.

“I kept asking the Institute for a solution, but they never gave me an answer.” In 2018, “a violent lawyer, a threatening police officer, and a notary showed up at my house. They told us the house didn’t belong to us. That they had received reports that it was abandoned. I started looking for lawyers because I received a notification that my husband and I were being taken to court. At the hearing with Judge Daniel Cobos, they wouldn’t accept my evidence. They told me my mother didn’t live in the house, even though, because of her disability, she was under my care.”

Alexia visited the provincial human rights and gender diversity secretariats, as well as the municipality of Godoy Cruz. “The judge hid behind the fact that they had the deed. He doesn't care that I'm transgender and that my husband is disabled. Then the pandemic hit, I lost the case, and they gave me two months to vacate the house. That's why I'm desperate; I don't have the money to pay for more lawyers or find a place to go.” This concludes her account of a housing emergency that is commonplace among many trans women and transvestites.

Morena's struggles : housing, work, education

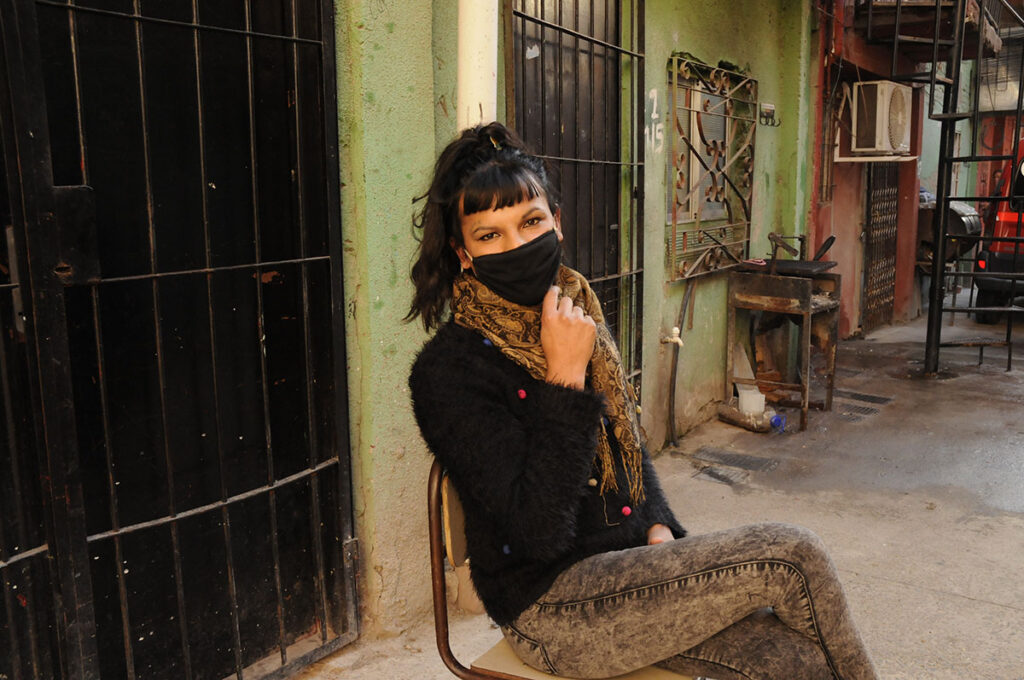

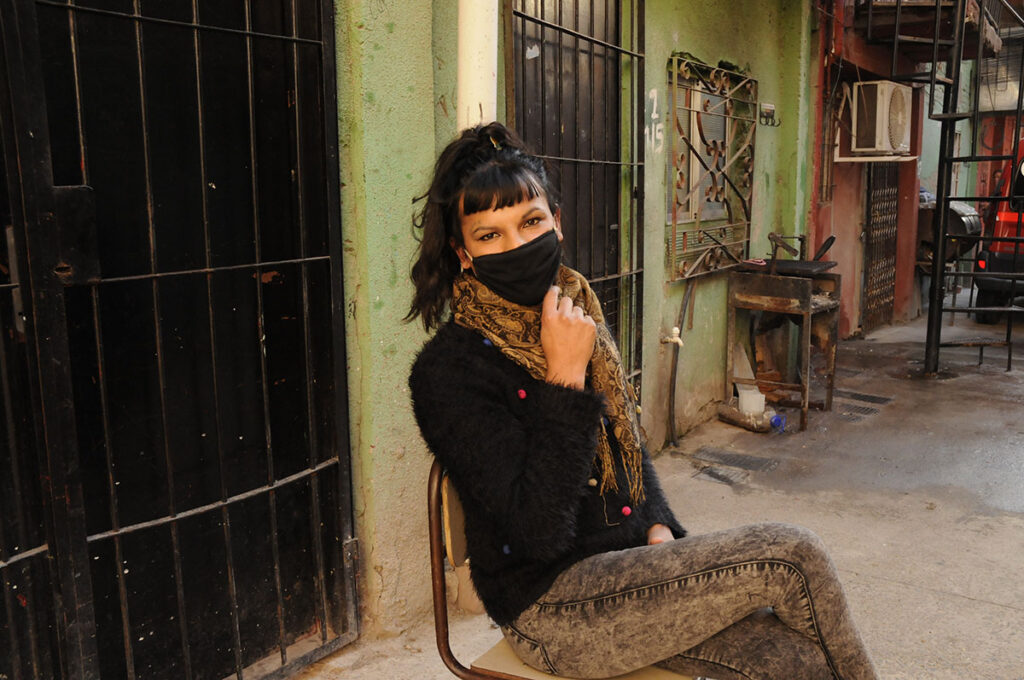

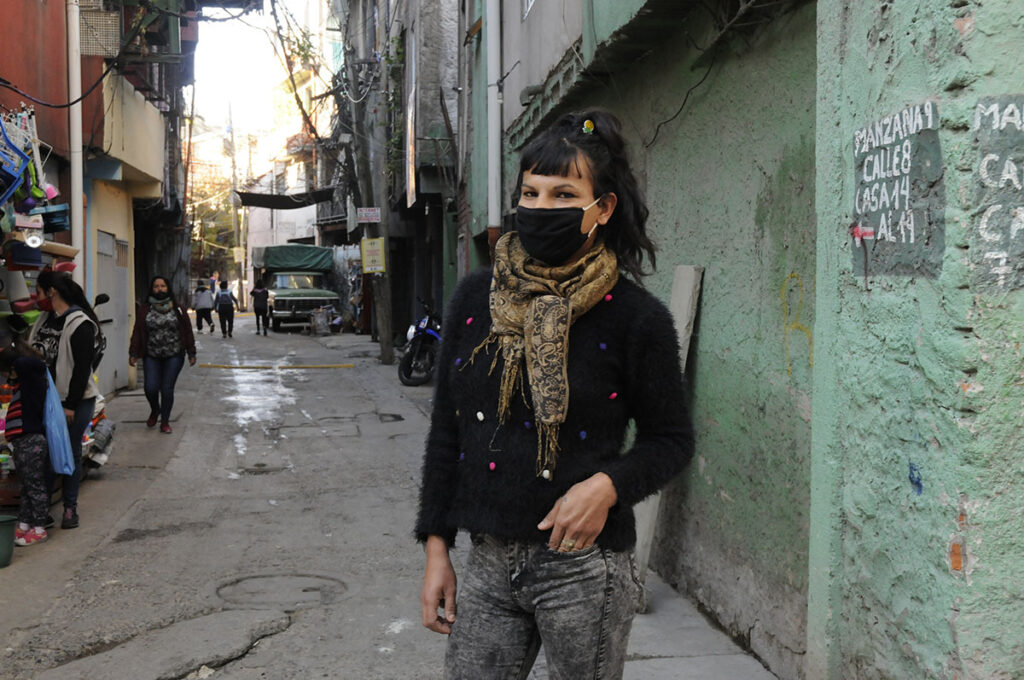

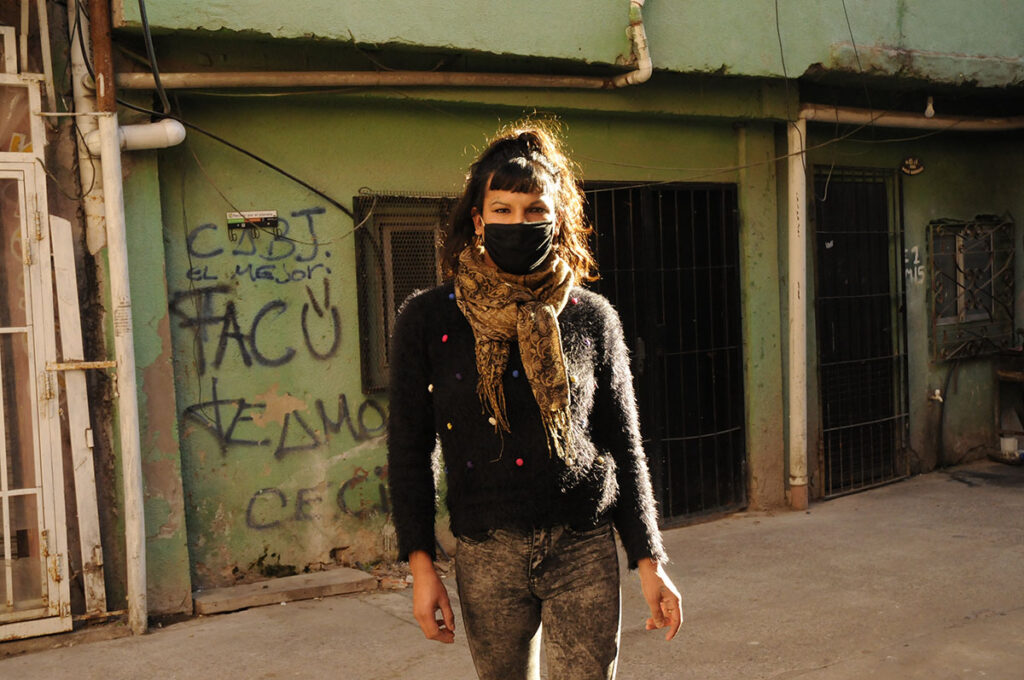

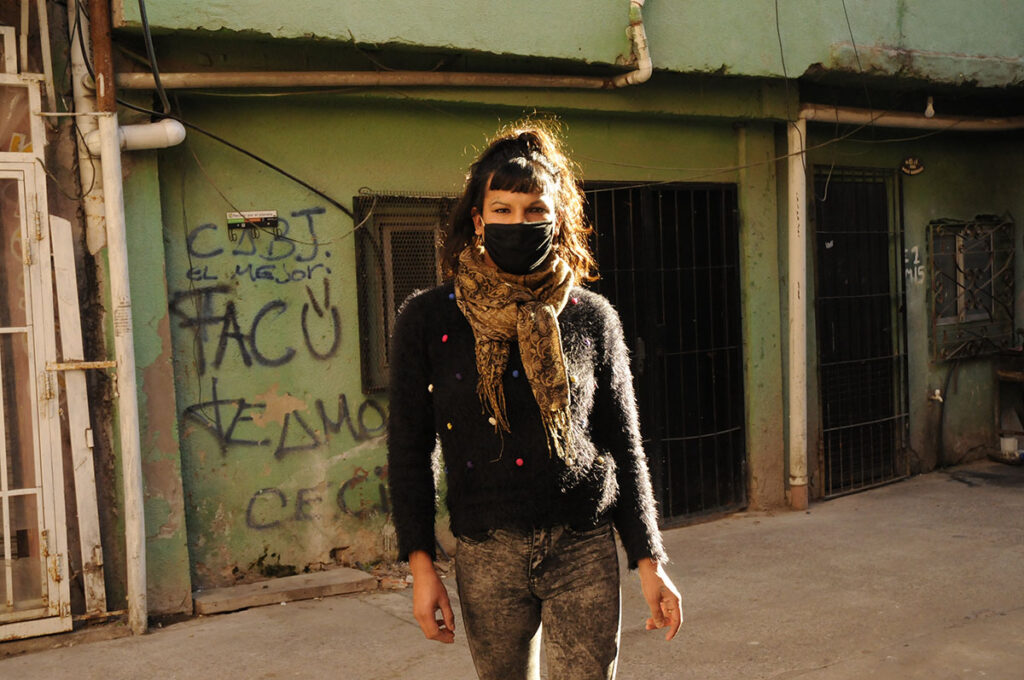

Morena Contreras is a student at the Mocha Celis Trans and Travesti Popular High School. Originally from the province of Tucumán, the best strategy this young trans woman found to escape "the plague," no matter the cost, was to come to the capital to find a job and finish her studies. While weaving dreams of trans and travesti employment inclusion, Morena lives in Barrio 31 in Retiro (formerly Villa 31). A few days ago, she was evicted. A woman who knows her lent her a small room, where she is currently living with the bare necessities.

She's been waiting for weeks for a call from a social worker. She says she's been waiting since October to be cleared to access the Potenciar Futuro program. Meanwhile, Morena wanders the streets of the shantytown and enjoys watching the moon set over the highway on cold nights.

According to data published in *The Butterfly Revolution * (a study on the situation of the trans population in the City of Buenos Aires, prepared by the Gender and Sexual Diversity Program, the Divino Tesoro Foundation, and the Mocha Celis Trans Popular High School), in 2016, 65% of the transvestite and trans population in Buenos Aires lived in vulnerable housing conditions, and more than 25% in critically overcrowded conditions. Only 31.9% of the population was formally employed.

We know these facts, and we've lived them. And they've gotten worse. The economic situation also deteriorated during four years of Macri's administration at the national level. In the city, under Larreta's administration, our group has no more room to maneuver.

It is worth noting that in 2008, the courts ruled that the Government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires had to take substantive measures to address the lack of access to housing and employment for the trans and travesti population. In July 2020, three Buenos Aires legislators—Ofelia Fernandez, Lorena Pokoik, and Victoria Montenegro—introduced a bill to declare a Housing Emergency for trans and travesti people in the City of Buenos Aires .

We know they haven't taken any real action; all they do is put the rainbow colors on the obelisk once or twice a year. Even the poorest among us knows that won't put food on our tables or guarantee us a roof over our heads. We need answers urgently.

Housing neglect is social transvesticide. Our struggle is a class struggle, waged in the streets, amidst our own and collective miseries, sometimes for food, other times to shout for Tehuel. Our struggles are fueled by love, tenderness, and fury. Even when a solution is lacking. Transvestite and trans housing inclusion now!

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.