Here we are, the trans moms!

Many realities come to light when becoming a mother, but one of them is often denied or ignored. How do trans people experience motherhood?

Share

“Twenty-four years ago, I could have said no or let it go, but it has filled me with goals, happiness, and joy. I have someone to fight for, someone to think about, someone to wake up to, just like anyone else who chose this path. My children are the driving force of my life and have shaped my story. As a trans woman, nothing will prevent me from enjoying these rights: having my children, my own family, which breaks so many stereotypes. Today I can say that I have an extraordinary family.”

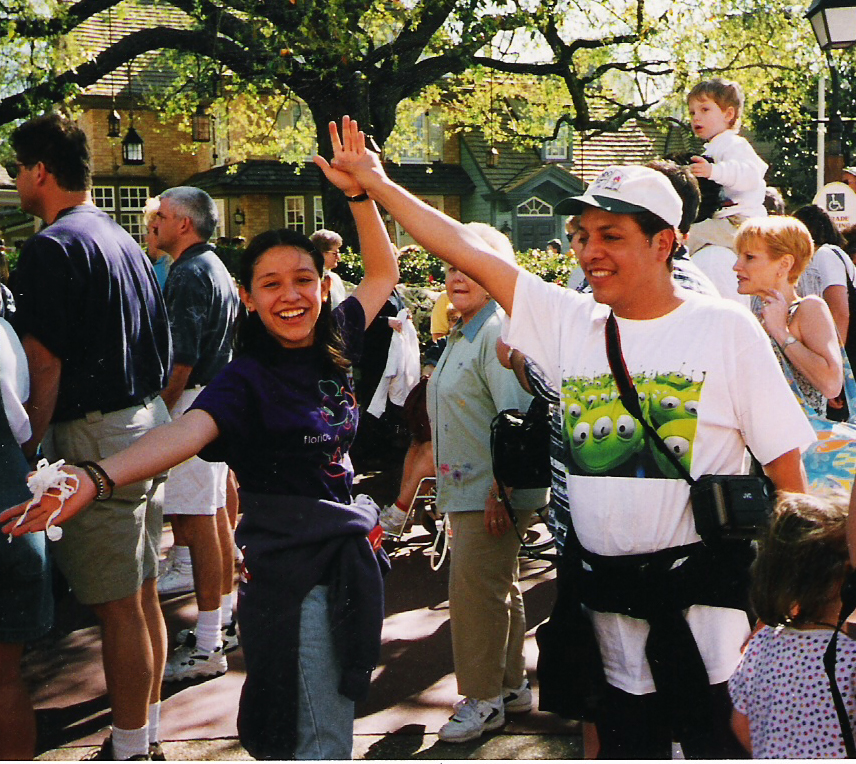

With her small, bright eyes, Oyuki Martínez smiles as she answers a video call question about how she defines her experience of motherhood. This 43-year-old trans woman, who lives in Iztapalapa, is not only the mother of six children—as she refers to them constantly—but also a human rights advocate and holds a degree in Political Science and Urban Administration from the Autonomous University of Mexico City.

Later, Roshell Terranova, actress, activist, and businesswoman, answers the call via video call from Casa Club Roshell, a cultural space for trans and travesti people that she directs. With blonde hair and always smiling, she responds to what it means to her to be a trans mother.

“It’s about having an opportunity and feeling proud: yes, I am a trans woman and I am a loving mother, provider, and educator. Even more so with the difficulties of being singled out by society that tells us we can’t be mothers or fathers because it’s believed we might give a bad education, set a bad example, or even abuse our children.”

Just like Oyuki and Roshell, there are so many other trans women who raise, educate, and care for others as their children. In our society, taking on the role of motherhood as a trans woman represents a break from what we've been told at school, at home, or in church about what a woman and a man should be and do.

Discussing transgender people and the experience of parenthood remains largely unexplored territory for research and journalism. This report aims to bring together two transgender motherhood experiences to shed light on realities often obscured by ignorance, prejudice, or lack of understanding.

Transgress the Cis-theme

Let's take it step by step. It's important to clarify that trans women are those who were assigned male at birth and identify within the feminine spectrum. In contrast, trans men are those who were assigned female at birth and identify within the masculine spectrum. In both cases, their gender identity is valid regardless of where they are in their transition, that is, whether or not they are undergoing hormone replacement therapy or whether or not their self-perceived gender is recognized on their identity documents.

So what is gender identity? It's the internal experience of how each person feels it, and it may or may not correspond to the sex assigned at birth. When it does correspond, the person is cisgender, and when it doesn't, the person is transgender. Specifically, everyone has a gender identity, and it will never be the same as sexual orientation, which is basically who you are emotionally, erotically, and sexually attracted to (homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual, etc.).

All people enjoy these characteristics because they are part of human sexuality; however, gender is a complex system of social hierarchies that are constituted by the characteristics we give to the body once we are classified as women or men at birth.

Within this sex-gender system, there exists a mechanism that privileges cisgender people and excludes transgender people. These mechanisms exist because there are prejudices surrounding transgender identities, where it is assumed that their experiences, rights, and material and symbolic spaces are less important and relevant than those of cisgender people.

Under the current system, trans people are not expected to be mothers, fathers, or both, because their existence is still surrounded by stigma, discrimination, and violence. However, trans mothers and fathers do exist; their ways and experiences of building a family are diverse, largely invisible, and they are not usually protected by state institutions.

***

When Oyuki was eight years old, she realized that her body and mind did not align with the gender she was assigned at birth. From the age of twelve, the instances of physical and psychological violence in her family, school, and social environment intensified, as she herself recounts: "for not conforming to the norms."

In 2015, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights established in its report on Violence against LGBTI Persons in the Americas that systematic violence is perpetrated against transgender people, especially women. This document explains that the family is often the first place where they experience violence and exclusion. As a consequence, their rights are violated: the right to education, housing, health, and access to formal, well-paid employment.

In that sense, Roshell says she is “fortunate.” “ My family never repressed my gender identity, nor my processes, my exploration, but I did experience the times of police raids, criminalization, and in those years there wasn't much information, and although at eight years old I realized I was different, it took almost 20 years for me to accept myself as a transgender woman and realize that there were other possibilities of being trans, that is, not occupying the sordid, violent place where society puts us,” she explains.

Trans mothers by choice

“ Because of the limitations imposed by society—that as trans women we can’t be mothers, we can’t be loved, we can’t start a family, or that we’re destined for sex work—being a mother wasn’t something I thought was possible for me. But when my children arrived, it was a turning point . At 18, I chose to be responsible not only as a father figure but also as a mother, and it’s something that makes me very happy. But I also understood—upon becoming a trans mother—that it involves fighting against institutional and social prejudices and breaking down stereotypes and dichotomous views of what it means to be a father, a mother, and also what it means to be the child of a trans mother,” Oyuki explains.

Oyuki's family consists of Tere, her mother; her daughter Sorey, a teenager studying psychology; five children in elementary school: Iker, Carlos, Edwin, Donovan and Neytan; and her partner.

Oyuki's daughter and children have been raised alongside Mrs. Tere, whom they also call "Mom." Together they have taken care of them since their biological mothers, "because of their life stories, being survivors of violence and their circumstances, decided not to assume this responsibility since they were very young mothers," Oyuki explains.

—What do your children call you?

“They call me mom, dad, mom-dad. They also call me Oyuki because I have taught them that we are similar, neither my age, nor my identity, nor my place in the family are barriers to building trust,” she says.

—When they call you Dad Oyuki, how do you feel?

"I didn't like it before, but now it doesn't bother me because I understand that being a mother or father isn't just about biology. It's about a bond."

Roshell's story is similar to Oyuki's in that assuming her role as a mother also happened by chance. A little over thirty years ago, Roshell met Paola, her daughter, and six years ago, Luna, her granddaughter.

“My sister Maru decided to be a single mother. That's how Paola came into my life. In her childhood, Paola started calling me 'Dad.' At the time, I identified as a gay man and was the only male figure in the house. As time passed, I found myself and embraced my identity as a trans woman. It was through my transition that I became a mother, because Paola saw me as her second mother, and I embraced being a trans mother because I've always been there for her financially, morally, and emotionally. That's how we developed this relationship, this bond of mother and daughter,” Roshell recounts, her voice filled with emotion.

Paola joins the conversation and I can't help but ask — what was it like growing up with a trans mom?

“Growing up in diversity has been an amazing experience because not everyone has the opportunity to learn about it, to delve into this world, to respect it, to understand it. I feel part of the diverse community even though I'm a cisgender woman because from the very first minute of my existence, I've been part of this community. And when I had this conversation with Roshell—I didn't know her yet, although she's obviously always existed—the picture became clearer because I saw a happier, more fulfilled woman. For me, it was perfectly normal to go from addressing her with male pronouns to female ones,” she says with a big smile.

Mexico does not (re)cognize its trans population

In Mexico, we don't know how many families are like Oyuki and Roshell's.

According to the latest INEGI survey, 40% of households in Mexico City are headed by women. However, the statistics don't account for the inclusion of trans women as heads of households because their gender markers only include two options: female or male. And what's the problem? Well, limiting the options to the binary model prevents us from understanding the existence, needs, and experiences of trans people.

In Mexico City, since 2014, transgender adults have been able to change their name and gender on their birth certificate. Same-sex marriage was legalized in 2009, and by 2010 the Civil Code recognized the right of adoption for these couples.

Furthermore, the local Constitution recognizes and protects “all structures, manifestations, and forms of family community with equal rights.” In addition, the section on LGBT rights specifies “the equal rights of families formed by same-sex couples, with or without children.” Under these provisions, trans motherhood, trans fatherhood, and the diverse ways in which trans people construct their families should be protected.

“If the absent parents show up and want to take my children, I have no legal recourse to prevent losing them. In the Civil Codes, in family law, we don't exist; trans people aren't included. So what, do I have to come out as gay and get married under a gender identity that isn't mine in order to adopt as a same-sex couple and fulfill that family construct?” —she pauses— “Not only are we not included in the discourse on diverse families, we need to be included in the law,” Oyuki replies indignantly.

She adds, “ At this moment, I don’t have any legal document to prove they are my children .” For Oyuki’s relationship with her children to be recognized, she would have to initiate a lawsuit—a lengthy and expensive process—hoping that the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on family diversity would be applied, since the Civil Code reforms regarding adoption by LGBT individuals are limited to same-sex couples.

When discussing diverse LGBT families, the common denominator remains same-sex parent families. Families headed by transgender people are rarely considered.

—How can we include trans women and men who build a family within the legal framework and the category of diverse families? responds Janet Castillo, coordinator of the sexual and reproductive rights clinic at LEDESER, an organization that seeks to guarantee access to justice, civil, sexual and reproductive rights without discrimination for LGBTI populations.

“There is an urgent need for Civil Codes and secondary laws to be aligned with the progressive criteria of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, which recognize the experiences of diverse families. This will only be possible through a reform of family diversity that acknowledges the experiences of gender non-conforming people and their family structures. Another way is to continue making the experiences of transgender people visible, which is fundamental to breaking down the prejudices and stigmas that are also perpetuated by the law.”

Love, humility, and respect

On more than one occasion, due to the lack of a legal document that proves Oyuki's motherhood, the teaching staff have committed acts of violence against her and her children simply because she is not legally recognized as a 'mother or guardian'.

“Teachers and principals take advantage of this situation to abuse, stigmatize, generate prejudice, and create an environment of violence. In preschool, one of my children asked permission to go to the bathroom, and the teacher wouldn't let him. She overpowered the child. I wasn't informed until dismissal time. Strategically, the principal omitted the complaint process because only the mother or father could do so, and for her, I wasn't his mother or father. To this day, the institution hasn't acknowledged its wrongdoing, and the teacher hasn't been sanctioned for the act of violence against my son,” this is one of the experiences of discrimination and violence that Oyuki's family has experienced in school settings.

In that sense, Janet Castillo from LEDESER reminds us that "any act that restricts the family rights of a trans father or mother, because they are a trans person, is an act of discrimination that can be grounds for a complaint or report."

Oyuki and Roshell agree on the importance of educating based on love, humility, and respect.

“I think it’s fundamental that there be respect and inclusion for others. I trust that from within our families, we can break down all these mechanisms of heteropatriarchy, prejudices, stereotypes, and stigmas. My children and my family have the tools to defend ourselves, but also to make it clear that other ways of being, feeling, and thinking are possible for a culture of respect,” says Oyuki.

Roshell concludes, “Educating with love, respect, and information will help us overcome fear. We fear what we don’t know. Not opening ourselves to love, respect, and empathy can prevent our children and our own experiences as trans mothers from being happy, and we deserve that too. Here we are, trans mothers!”

This report was made with the support of Chilango and is part of their May special for Mother's Day.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.