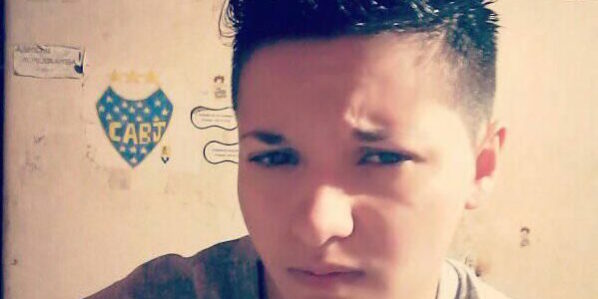

"Tehuel de la Torre was disappeared by transphobia"

Activist Ese Montenegro analyzes the context of the disappearance and search for Tehuel de La Torre in Argentina and focuses on the structural violence suffered by trans men.

Share

That Montenegro

This Sunday, April 11, marks one month since Tehuel de la Torre, a 22-year-old trans man from the greater Buenos Aires area, left his home for what he claimed was odd jobs—yes, odd jobs, because we know that formal employment is something else entirely—and never returned. Two people have been arrested in the judicial investigation: Luis Alberto Ramos, the person who offered him the job and with whom Tehuel met on the day he disappeared, and Oscar Alfredo Montes, a scrap metal collector and friend of Ramos.

From what little is known about the case, both defendants are currently refusing to testify and the investigation is being kept under "summary secrecy" so the transvestite, trans and non-binary organizations that have been demanding their safe return have practically no data or accurate information on how the case is being handled.

The trans, non-binary and transvestite communities can ask ourselves many questions and approach some answers and assessments of what the disappearance of Tehuel imposes on us so far.

The justice system prioritizes blood relatives.

First: Without intending to specifically question anyone—although if anyone feels alluded to, discomfort is welcome—our trans, travesti, and non-binary communities have a history of collective construction that clearly challenges—hopefully to the point of imploding—the cis-heterosexual logic of forming and thinking about relationships. Especially the social, political, symbolic, and material relationships that are assumed to be embodied in the figure of “family.”

We are often excluded, marginalized, and subjected to violence, first by our cisgender heterosexual families when we identify as trans, transvestite, or non-binary people. Driven by this initial exclusion from our cisgender heterosexual families, we build communities and explore alternative paths around what family means and represents to us. But this construction and experience never achieves recognition, for example, from the State and its institutions. Therefore, in situations like the one embodied in Tehuel—to return to the example that challenges us—the justice system prioritizes a blood family over any other relational experience, even if that family may not recognize or deny the identity rights of the trans, transvestite, or non-binary person involved.

But it's not only the State that hierarchizes this structure, reducing it to the blood family; our communities also fluctuate within this tension, because this form of social and institutional construction—of a cisheterosexual nature—has also produced meanings for us. We are not exempt from this contradiction, but at least we add other variables, experiences, and paths that, far from challenging the family, transform it: Yes, our families also include other transgender, queer, gay, bisexual, etc., people with whom we share our lives and who should be understood as such, because many of us live and exist in/with these communities and not in the others that legal status dictates.

Lack of access to work

Second: Another question that must undoubtedly challenge us is the one related to access to work. It is not because of this pandemic that is ravaging us that transgender people (TTNB) do not have access to formal employment; this exclusion is structural, historical, and political. Following the exclusion of our biological families, we are then excluded from educational institutions, and this limited access to training translates into a structural exclusion from the world of formal work. And yes, we emphasize formal work because a large part of our communities maintain their economy based on informal, precarious jobs, often criminalized by state policies . Because we are communities with productive capacities, we recognize ourselves as workers, and we have a potential that has much to contribute to the world of work, but that opportunity is denied to us . Under the pretext of a lack of training, under the pretext that our gender expressions do not fit the binary and cis-sexist mandates of "good appearance." And also, because many of us have been criminalized for our gender identities, we have criminal or misdemeanor records due to the persecution that security forces carried out—and in many cases continue to carry out—against us when we appear in public spaces. This record is used as an impediment to accessing formal employment. Not only were we criminalized, but based on that criminalization, we are excluded from the formal workforce. That is why it is vital to continue demanding the approval of the National Law on Quotas and Labor Inclusion for our community. Because where the state has caused harm—through action or omission—it must provide reparations.

Tehuel is not a "case" nor something isolated

Third: Tehuel's disappearance highlights structural issues—issues that almost no one talks about, except within our communities—issues that cannot be reduced to a single case or a particular cause. They are the foundation of structural inequalities that, as a clear result, have led us to spend a month searching for a trans man. The fact that assemblies and the mass media are discussing "the limited visibility of trans men" once again focuses attention—and the burden that entails—on a community that is constantly subjected to erasure, as a discipline that demands we prove our existence and our continued resistance to cisheterosexual cruelty.

All the time, we are required to "appear" (as the performative act of making ourselves visible in the face of the inability of others to see us) but there is never any thought or talk about who and how each time, systematically, has made us invisible, has made us disappear from their stories, from the struggles, from a community with history, from movements of trans men that are always present and always diminished by cisexism and transphobia, even within our own communities.

For a trans-feminist judicial reform

Fourth: And not as a footnote, but as a matter of urgent concern, it is evident that this judicial system, with its clear patriarchal, heteronormative, and biased nature, is incapable of understanding—in all its complexity and specificity—our experiences and ways of living. A justice system that still does not understand—and therefore does not address—how sexism (binary and heteronormative) distributes privileges and violence between men and (cis) women is far from understanding and grasping our realities, which are generally disruptive to the heterocissexual logic and which even come at a high price for breaking with this social mandate that organizes everything. An example of this is that, after years of struggle following the transphobic murder of activist Diana Sacayán—one of the driving forces behind labor inclusion laws in Argentina—the First Chamber of the National Court of Cassation, last October, removed the classification of transphobic murder as a hate crime specifically related to our comrade's gender identity.

When it's said that the judicial system requires feminist reform, it should also be said that this reform demands a profound, sincere, and restorative critique of a system that only orders and distributes rights and obligations to cisgender heterosexual people, leaving those of us who don't conform to this system only with a place of criminality and incomprehension. Perhaps considering it from a transfeminist perspective could be a more enriching approach, but one that certainly shouldn't exclude other intersections that condition us, in addition to gender, such as racism and structural ableism, our class, age, geographic, linguistic, and communication differences, among others. If reform isn't carried out from an intersectional and gender-sensitive perspective—with a gendered "gender" and in the plural—it will continue to be simply injustice in practice.

Tehuel's disappearance challenges us, distresses us, and calls us to critical reflection. Tehuel's disappearance speaks volumes about the silences, erasures, and violence that are historically, politically, and structurally present in our society, resulting in a trans man who has been missing for a month and a series of specific practices—such as cissexism and transphobia—that go unexamined, unnamed, and that, as long as we continue to conceal them, will continue to create the conditions for other disappearances..

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.