Toolkit for dealing with transphobic rhetoric

Presentes brought together human rights defenders, and trans and feminist collectives from Mexico to put together a digital toolkit.

Share

By Georgina González

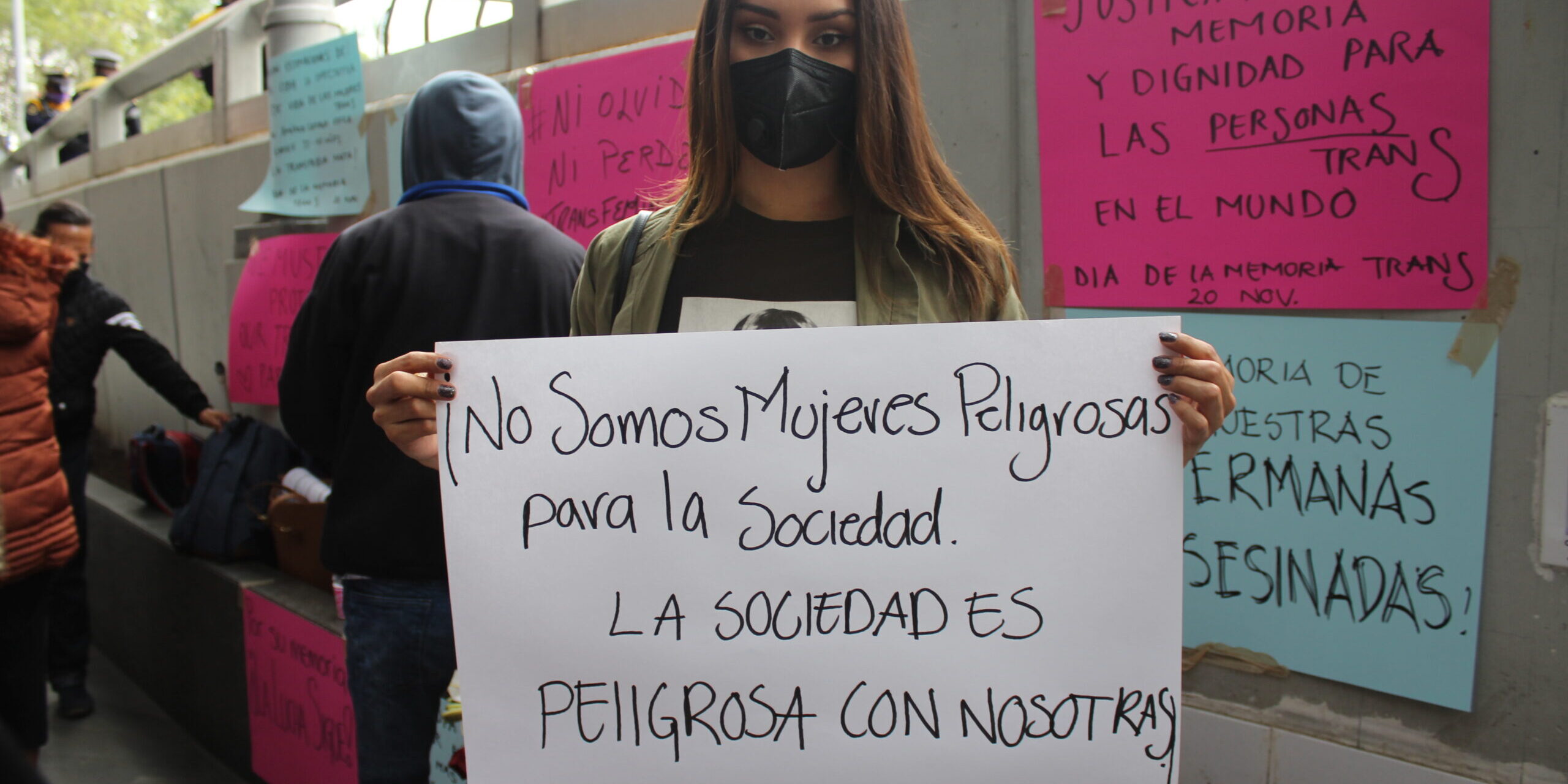

In recent years, we have seen an increase in transphobic rhetoric in Mexico. This is especially prevalent on social media, but this confrontation also spills into the streets when trans-exclusionary feminist groups use graffiti to oppose the recognition of gender identity. These groups question the existence of trans people and claim that their presence jeopardizes the spaces and rights achieved through what they call "the erasure of women." Furthermore, transphobic pressure recently led the media outlet Milenio to censor its contributor Láurel Miranda .

Given this situation, Jessica Marjane, a human rights defender and coordinator of the Trans Youth Network , warns that “many of the discourses they use are not new. They (exclusionary trans feminists) are simply appropriating them and turning them into a supposedly legitimate struggle, and if we think that combating hate speech is the only goal and that the struggle will be to demystify it, we are falling into the trap. I feel that this is a call for a hopeful present and future, a defense of the future so that trans people can strengthen themselves with emotional, methodological, human rights defense, discursive, affective, and economic tools—tools for life.”

Presentes brought together human rights defenders, and trans and feminist collectives from Mexico to put together a toolkit of digital, communicative and legal resources to combat transphobic discourse.

How to identify transphobic discourse?

Janet Castillo, coordinator of the legal clinic on sexual and reproductive rights at the organization LEDESER, clarifies in an interview that “hate speech is not and cannot be considered the same as defamation or slander, since it is not only false accusations that seek to cause harm, but is related to structural and systematic violence towards historically vulnerable groups that favor stigma and prejudice against them.”

For her part, Sofia Jiménez Poiré, a member of the Dignas Hijas Collective , proposes to qualify the concept of “hate speech” as “stigmatizing speech or anti-rights speech” because “they do not appear to be hate speech but rather are speeches in defense of a group.”

And she adds that, “one reason why (these discourses) are so successful and why people subscribe to them without seeing themselves as cruel, evil, or unjust is because they are based on three pillars: the acceptance of the truth; the portrayal of the enemy; and the flattering self-portrait. Pillars that are also found within the TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) discourse.”

- The meaning of truth.

“They will allude to science, they will try to support what they say with studies and they may not necessarily cite the source but they will say: 'biology has shown that…', to generate trust and credibility in the audience, they throw out names of feminist theorists and begin to have power dynamics to reiterate their idea that they are the ones who have the truth.”

Faced with this rhetoric, Sofía observes two disadvantages: “there is ignorance regarding the functioning of science and the processes of production of scientific knowledge (…) the so-called hate speech takes advantage of this to make false and deceptive quotes, and tends time and again to say 'it is not transphobic to tell the truth'.”

2- The portrait of the enemy

“An enemy force will be identified. Generally, to avoid transphobic accusations, the focus is not on people's sexual identity but on their behavior, and these profiles will be loaded with stigma.”

Sofía observes that there are two ways to portray trans people negatively. One is by highlighting individual cases "to suggest that some trans women are dangerous and therefore dismiss the rest of the trans women." The second is through general stigmatization, where "trans women are presented as caricatures: having beards, hairy legs, a deep voice; not because these characteristics are inherently bad, but they are presented in a way that aims to generate a reaction of disgust that is repellent to cisgender women."

3. Flattering self-portrait

“They portray themselves as saviors, defenders, and victims. With the supposed “erasure of women,” they revive the idea that women are under attack, that we need to defend ourselves, that we are victims of censorship, and having that card helps them to have a favorable vision to generate internal cohesion and deep conviction.”

At this point, Sofía comments that these enabling factors make it difficult to recognize discourse that stigmatizes and reproduces violence. “This happens especially among cisgender feminists; we aren't recognizing the impact, the potential, and the danger. We don't confront it, and we remain silent, and that silence ends up being complicit because we have a very black-and-white view that makes it difficult to easily recognize when it's hate speech. Because, precisely, it's not hate speech, and that's why I advocate for alternative expressions, because they fly under our radar,” she explains.

To encourage non-complicity, in August the Digas Hijas Collective launched #NoEnNuestroNombre , a statement in support of trans identities and against "trans-antagonistic discourses that call themselves feminist."

“Yes, there is erasure of women, but not of trans people.”

queer activism conspires against women to make them invisible, take away our rights and therefore continue with the systematic and structural violence that we have historically suffered (…) Under this discourse any trans person will be recognized within this theory as a threat to women,” explains Janet Castillo.

And this happens especially when the use of restrooms is debated; sports; sexual and (non)reproductive rights are discussed, menstruation is discussed, or when dates like March 8th —International Women's Day—approach. It is then that voices from a "white, heterosexual, cis" feminist perspective argue that trans people threaten their hard-won spaces and rights.

According to Jessica Marjane, “there is indeed an erasure of women, but it's not trans people who are erased.” She explains that “the erasure is done by the patriarchal, sexist, racist world; it's done by institutions when spaces are occupied by men from sexist, androcentric perspectives; when women have fewer job, academic, and health opportunities to integrate their professional, personal, and community lives.”

For her part, Liz Misterio, co-founder of Hysteria! magazine, emphasizes that “accepting our differences doesn't erase or diminish the effectiveness of our struggles, but rather adds facets to dismantling the patriarchal system (…) when I started going to feminist marches about 10 years ago, there were very few of us, a couple of hundred at the march for abortion rights on March 8th, but in all of them I remember marching alongside women, trans men, and non-binary people who understood that the patriarchal system that oppresses us is the same. I recognized myself in experiences that may not have been identical to my own, but in whose origins and consequences I could see myself reflected.”

How do these speeches affect us?

Feeling threatened, transgender people are often targeted by cyberbullying and defamation. For Jessica Marjane, this situation is causing a great deal of silence and isolation. “Seeing so much misinformation and so many attacks makes it even crueler because these actions are justified under the guise of freedom of expression,” she says.

As a result of digital violence and the “bombardment of misinformation,” Marjane has experienced episodes of anxiety, panic, fear, and uncertainty both online and on the street. “I not only have to protect myself from people who explicitly express their transphobia, but also from those who claim to respect diversity but aren’t. And given the medical negligence that exists regarding our bodies and minds, trans people have to seek spaces for listening and healing. Taking care of ourselves also means shouting, crying, and exhausting ourselves, but without taking control. We are more than those narratives,” she maintains.

From 2019 to February 1, 2021, Visible , an observatory of LGBT+ discrimination and violence in Mexico, recorded 62 incidents of online violence; 19 of these cases were against trans people, 11 of them against trans women. Furthermore, during the first months of lockdown, digital violence increased.

As with trans femicides, digital violence against sexual minorities in Mexico is not documented by the state. Visible's efforts offer only a glimpse into the situation; however, official statistics are needed to properly assess the scope of this problem, develop prevention strategies, and provide support.

Furthermore, in the context of Latin America where the life expectancy of trans women is 35 years, the IACHR proposes that in the face of hate speech, States “should promote preventive and educational mechanisms and encourage broad and deep debates, as a measure to expose and combat negative stereotypes.”

Can they be reported?

The Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) affirms that hate speech is contrary to the values on which human rights and democracy are based, such as equality, dignity and even freedom of expression, since it promotes discrimination and violence.

Despite this clarification, in Mexico there is no specific legal path to protect oneself against hate speech because “while the Constitution establishes that the right to freedom of expression is not an absolute right and has limits when it affects the rights of others, there is no express regulation regarding this type of speech,” explains Janet Castillo of LEDESER.

TWO ALTERNATIVES

- Filing a complaint for discrimination or violation of any human right with COPRED , CONAPRED , or the state or national rights commissions is an accessible and responsive process, as these procedures are free and generally handled by trained and sensitized personnel. However, it has limitations, particularly regarding the scope and effectiveness of these organizations, which only handle complaints against public officials.

- Initiating a civil lawsuit claiming damages or moral harm caused by such speeches is an option. However, limitations of this approach include its high cost in terms of both money and time, the risk of revictimization by judges, and the difficulty in proving damages, as these do not always translate into material losses that can be 'proven' through traditional legal expert reports.

How can we protect ourselves in digital environments?

To learn about basic care measures in digital environments, we consulted the Luchadoras , and Andras Yareth from Resistencia No Binarix , who together with Rancho Electrónico coordinate workshops and information on digital self-defense for non-binary people.

- Review the tools offered by any social network to report situations that put our information and integrity at risk.

- Be clear about what information we share on social media.

- Use strong passwords for emails, social media, banking apps, etc.

What if we are under attack?

- Not responding is also a strategy. “Online hate is overwhelming; taking a break is valid.”

- Ignore the troll: blocking and muting is a protective barrier. "You don't want to invite nasty people into your home."

- Documenting the attack allows us to know if the hate messages we're receiving have the potential to escalate beyond the virtual realm. "Documenting it yourself is very difficult; ask a friend for help."

- Some platforms have word-blocking tools. “You can add them to your banned words list and prevent them from appearing in your timeline or in comments during live streams.”

- Tell someone. “Virtual and in-person listening and support spaces are another way to build relationships and support each other in the face of violence.”

What can be done in terms of communication?

In response to the rise of transphobic discourse, Hysteria! has dedicated two thematic issues to discussing the transfeminist struggle, and since its founding has given space to trans artists and “thinkers”.

“We recognize that the power of their actions and their thinking is vital for understanding intersectional feminism, and that public and affective alliances nourish our movements of dissent against the patriarchal system. If we want to see this system fall, it is vitally important to add voices to the struggle and leave no one behind,” says Liz Misterio.

Historically in Mexico, the media has presented the life—and death—travels of trans people through narratives that perpetuate stigma, pathologization, and criminalization.

To break this chain of symbolic violence from communication spaces, Luchadoras proposes the following strategy.

- Create counter-narratives co-created with trans people.

- Uniting platforms to create a counterweight.

- Open spaces for expression, confront censorship.

- Use a language that breaks down binaries.

- Hacking victim-blaming media narratives.

- To recognize trans people in all their creativity, trajectory and contributions.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.