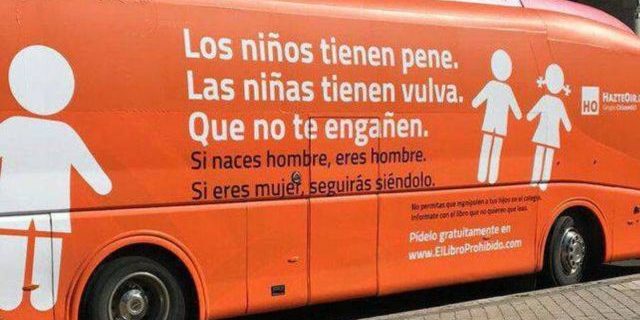

Chile: The return of the hate bus

"Hate speech and human rights denial are not part of freedom of expression." By Constanza Valdés.

Share

More than a week ago, Marcela Aranda, director of the Christian Legislative Observatory and a well-known opponent of LGBTI rights, announced the return of the so-called "Freedom Bus," which had already made appearances in various cities across the country in 2017. This announcement comes in the context of the victory of the option for a new constitution, with almost 80 percent of the vote in favor versus 20 percent against in the October 25 plebiscite. Given this, any political analysis we undertake cannot exclude the constitutional process and its implications for society.

In 2017, when the orange bus arrived, it was intended to halt progress on LGBTQ+ rights, particularly the advancement of the gender identity law. Three years later, with the gender identity law in effect, several court rulings recognizing LGBTQ+ rights, and a constitutional process underway, the landscape is completely different. What Marcela Aranda and the bus represent is a defense of the status quo and the prevailing political and constitutional order. Similarly, in terms of public opinion, the rejection of what has been aptly named the "hate bus" has been far more forceful than when it first appeared.

The notion that hate speech and human rights denial are not part of freedom of expression . This is especially true given the sustained increase in crimes against LGBTQ+ people in recent months, exacerbated by the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. The government's silence surrounding these crimes, in particular, further deepens the vulnerability of LGBTQ+ people in terms of the recognition and protection of their rights. Neither legislative progress nor urgent public policy measures have been implemented in response to this situation.

Given the visibility of hate speech, the urgency of preventing hate crimes and implementing public policies is even greater. More than government-sponsored working groups, what is needed is a firm commitment to prevention campaigns, training for police officers on how to receive complaints, the integration of a human rights perspective into the investigation and resolution of these crimes, and relevant legislative advancements in this area. The government's persistent negligence and lack of interest further amplify the state's responsibility in this matter.

In this context, the constitutional process represents a historic opportunity to lay the groundwork for establishing guidelines and to begin a process of achieving justice regarding the historical situation of LGBTIQ people. In Chile, constitutions have always been designed by men and for men, so the fact that the next constitution will be drafted by a convention composed of 50% men and 50% women is an important starting point . Therefore, the participation of LGBTIQ people and organizations during this process is fundamental to enshrining their historically denied demands at the constitutional level.

With this in mind, the entire state structure must be designed to prevent the exclusions that have affected us, along with other historically discriminated and excluded groups. The struggle cannot be reduced solely to demanding the recognition of certain rights without considering how state institutions have played a role in the systematic discrimination and exclusion of LGBTQ+ people. What the bus and its slogans represent is precisely this: the historical discrimination and exclusion we have suffered throughout our country's history.

The return of the "hate bus" puts us, once again, on high alert regarding the recognition of our rights. This is especially true given that the very people who defend the arrival of this bus are the same ones who resist any possibility of changing the political framework of the current constitution. In light of this, in addition to the need to advance policies aimed at combating hate crimes, it is essential to discuss and establish demands regarding the new constitution in the area of LGBTQ+ rights, and particularly regarding violence, discrimination, and hate crimes. Chile has changed since 2017; we have heard this countless times in the streets. For this to be true, defending our rights, our very existence, and demanding our rights is, now more than ever, an urgent matter.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.