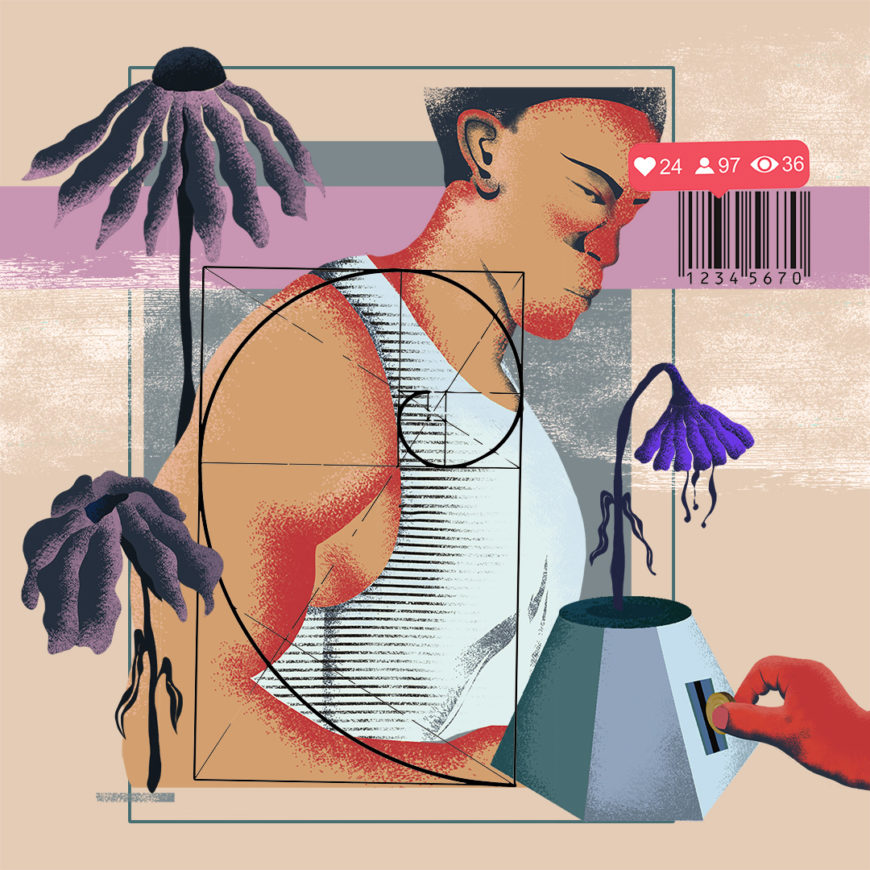

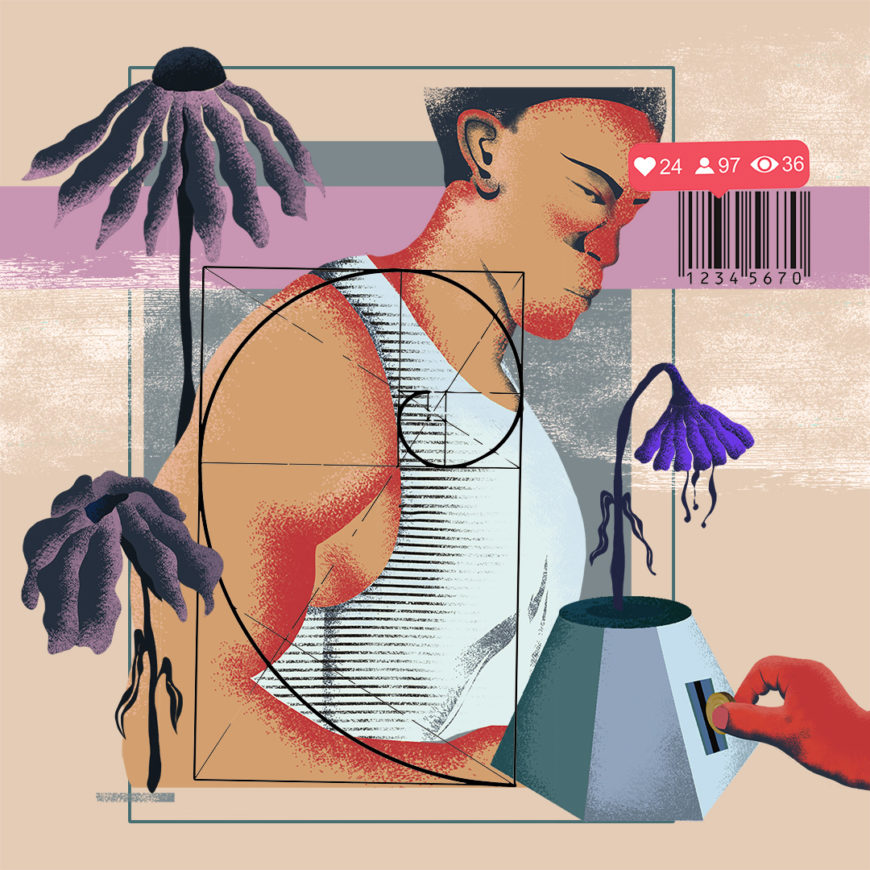

The laws of desire: digital image and queer body

Why do unreal normative pressures still operate on the political subject that is the queer body? By Enrique Aparicio.

Share

"Gay men have more means than ever to find and communicate with other gay men; we also have more opportunities than ever to reject each other."

By Enrique Aparicio / Illustration: Vane Julian / Pikara Magazine *

A few months ago, the popular actor Miguel Herrán posted a shirtless photo on Instagram , showing off his muscular torso, with the caption: “I think for the first time in my life I’ve looked in the mirror and accepted myself.” With 14 million followers, worldwide fame, and magazine covers praising his impressive physique , it’s hard to believe that one of the most sought-after male bodies doesn’t consider himself at the top of the desirability ladder.

Deceptive self-perception and validation through physical appearance—presented today through digital screens—which, perhaps following Herrán's example, has now reached heterosexual men, is one of the problems that has plagued the gay community since its inception. If thinking of a "gay club" still conjures up images similar to the promotional posters for the Circuit festival, it means that unrealistic pressures of normativity still operate on that political subject that is the queer body . Because no, when you come out of the closet, you don't automatically develop abs.

The only thing that unites gay men is our sexual and emotional attraction to our own gender. Although the experience of living in a heteronormative world connects us and leads us to create and inhabit shared spaces, their desire for other men is the only thing we know about our peers. Therefore, consciously or unconsciously, we have equated being a desirable individual with acceptance within our community. Being as appealing as possible to the greatest number of men is the best way to ensure we fit into gay spaces, often associated with hooking up and seduction—highly dangerous activities in unsafe environments . So it's not just about being liked, but about being sexually attractive at first sight, to stand out from the competition. Before, it was in clubs, and now it's on screens .

If one considers a certain common—though not unique—gay experience from a couple of decades ago, it's easy to empathize with the men who, closeted in their family and work lives and only surrounded by other gay men in the early gay bars and cruising , associated gay sociability with the circuit of desire: your worth among your peers is determined by how much you're liked. And to ensure that validation, the best strategy is to get as close as possible to the ideal body , the normative body . That body we all carry in our minds but almost no one actually has under their skin.

Although this logical consequence of being gay is the reason why certain aesthetics, fetishes, or categorizations have ended up generating subcultures within the community itself (bears are perhaps the best example of how an erotic taste has led to differentiated spaces of socialization, which establish their own rules regarding the bodies that comprise them), all gay men think they know that a normative body—that is, a muscular one—is a guarantee of validation. And if until a few years ago that pressure was concentrated in leisure time, the need to seduce others has devoured our entire routine through social media and dating apps . The time and place to be liked is now, between taps and stories , absolutely any time and any place.

Muscles, likes

I'm going to jump into the story to share a personal anecdote. Once, at a friend's birthday party, his roommate—who had been having a drink and chatting with us—went to his room shortly before we were due to leave for a club. As we were about to leave, he made an excuse and said he'd rather stay home. Later, I learned that the guy—who was handsome and had a great physique—had been doing push-ups and squats while we were finishing our gin and tonics in the living room. And that, unhappy with the results, he decided against coming to the party because he didn't feel pumped up enough to handle a visit to a gay club.

The gesture is perhaps extreme, but not without logic—and it's worth remembering that virginity or Adonis complex is a real psychological disorder, and that gay men are three times more likely than heterosexuals to suffer from it—because between this young man's gaze and his own body, we see reflected the hundreds of bodies to which we are exposed every day. Going to the gym—or to almost martial versions like CrossFit —is so institutionalized in the gay community that it almost functions as a collective ritual.

Images shared on social media, showing a sweat-soaked t-shirt or a dumbbell clutched in the hand not holding the phone, serve as a kind of eucharist for gay validation. They're proof that you're doing what you're supposed to be doing . On Instagram, an enviable physique is practically useless without defined pecs or sculpted thighs, in that millisecond when our followers have to pause to look at our body, amidst an endless scroll flooded with hundreds of other gay bodies.

On social media, guys with more muscular and defined bodies become stars, the leaders of the pack. Images of these guys, who follow training plans and diets worthy of elite athletes—and who frequently use Photoshop—become indistinguishable from those of magazine models or superhero movie stars. But they aren't actors or artists: their social media accounts reveal they're nurses, office workers, or waiters. The ideal body, in a perverse conclusion, is within everyone's reach. It's our responsibility to achieve it, and it's solely our fault if we fail.

And to further reinforce this pressure, we queers have obscenely fueled accounts and content creators who discriminate against the best bodies among those displayed daily on social media. Hugely popular profiles within the community, like @hoscos—which defines itself as “a window to creative images”—select photos from Instagram users to create a kind of pantheon of the most divine of these bodies, where diversity of form (and often also racial and gender expression) has no place. Appearing on this account or a similar one means ascending to the queer Olympus, receiving the blessing of those gods who look down on us from the stages of the WE Party.

Body and capital

If that ideal physique had been a rather abstract concept for decades, the arrival of Grindr measured and weighed the proportions of the norm. The internal logic of this dating app—and all similar ones—reduces users to digital profiles whose metrics allow others to approve or reject them. Height, weight, and distance in meters constitute an initial filter that the very use of the apps has extended to other standardized measurements, such as penis size (for which clothing sizes are used, so ironically, having an XXL is a positive thing) and more elusive but equally decisive characteristics. Like a binary code of desire, in these applications there are only 0s and 1s for almost everything . You are either masculine or you aren't, you are discreet (?) or you aren't, you are effeminate or you aren't (as if effeminate mannerisms were unique and permanent). In short, you are either normative (and therefore, valid) or you aren't.

In a diabolical exercise of neoliberalism, our bodies—our queer bodies, hardened in urinals and concentration camps, beneath and on the margins of the system—have become our capital. With the devouring of our bodies (or, even more twisted, their image) in devices that have been sold to us as technologies for connection—perhaps Grindr did work for that during its first five minutes of existence—the logic of capitalism has poisoned the intimate space of our carnal relationships.

Gay men have more resources than ever before to find and connect with other gay men; we also have more opportunities than ever before to reject each other. If someone with Miguel Herrán's body struggles with self-acceptance, the equation becomes even more complicated when you not only feel the pressure to have an ideal ideal body that attracts other ideal with whom, by sharing the same gender, it's inevitable to compare yourself. And even within their own 'ideal,' no two bodies are alike: the other guys are always taller, hairier, or better proportioned; they have broader shoulders or more powerful quads; larger trapezius muscles or a more pronounced hip curve. They're always better than yours in some way . The image-body-desire-validity machine never stops.

Or perhaps it can pause, for a few moments, in those alternative spaces that we gay men have also built from the beginning, where only darkness suspends the production line of our queer bodies. Those rooms where our bodies dissolve their shapes and sizes to rediscover themselves as hot and sensitive surfaces, the complete opposite of the dark glass of our smartphone .

*This article was originally published in Pikara. To learn more about our partnership with this publication, click here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.