LGBT+ seniors share their experiences of the pandemic in Latin America

Testimonies from LGBT+ older adults and the challenges of surviving the pandemic.

Share

By: Pilar Salazar, Airam Fernández, Vero Ferrari, Alejandra Zani, Paula Rosales, Juliana Quintana and Vero Stewart

Cover photo: Paula Rosales

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, one of the most invisible, marginalized, and neglected population groups worldwide has taken center stage. People over 65, "older adults," "the elderly," were relegated to a mass labeled "at-risk group." It suddenly became clear that most live alone, in nursing homes, or occupy a kind of marginalized place in family life. According to COVID-19 diagnoses, they were the first to die from the disease, the most vulnerable. This led, for example, to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) issuing a recommendation to protect the well-being of these individuals. Many are unemployed or lack access to pensions or social benefits. This economic vulnerability was compounded by increased discrimination in some countries, which, in an effort to protect them from the virus, further isolated them, as in the case of Sweden.

Being over 65 already involves a series of forms of discrimination. When this intersects with a non-hegemonic sexual orientation or gender identity, the violations of rights multiply.

Being an older adult and LGBT+ involves specific challenges, including having to build support networks outside of traditional systems, being excluded from nuclear families, having their partners not legally recognized by some states, and other injustices that are commonplace in many countries around the world, particularly in Latin America.

In turn, there is great diversity within the LGBT+ community itself, and the experience of a trans person over 60 (a true survivor, given that life expectancy in Latin America is 35 years) is not the same as that of a cis person of the same age. With them in mind, and considering their quarantines, we share some testimonies about how they are experiencing these times and what lessons their life stories and struggles can offer us.

"Being trans and older requires extra strength."

Jolie Totò Ryzanek Voldan is a 69-year-old Guatemalan transgender, bisexual, and feminist. She is a writer and advocates for the human rights of sexual diversity. She co-founded, with another woman, the first organized bisexual group in Guatemala called “Bi Guate,” which meets to raise awareness about this segment of the LGBTQ+ community.

Jolie speaks of the terrible and dehumanizing discrimination against the LGBTIQ+ population in Guatemala, something that is magnified because they are elderly. Considered a "risk population," their freedom of movement has been restricted.

“Every trans person faces challenges living in these patriarchal and heteronormative societies, which force them to ‘learn to be strong the hard way.’ And as the years go by, physical strength diminishes, and any beauty, whether great or little, turns into gray hair and wrinkles, further reducing the few opportunities we have to live. This is why being trans and older requires extra resilience , because you only have yourself and the support of those who stand by you.”

Without a retirement plan, due to a disability in her right leg and because she is transgender, she has found it difficult to find employment despite her extensive experience as an editor and proofreader. Before the crisis, she relied on her two daughters and close friends. But after the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, that support has dwindled, and simply surviving each day during the pandemic is a struggle.

"The struggle of older people and LGBT+ people: becoming political subjects"

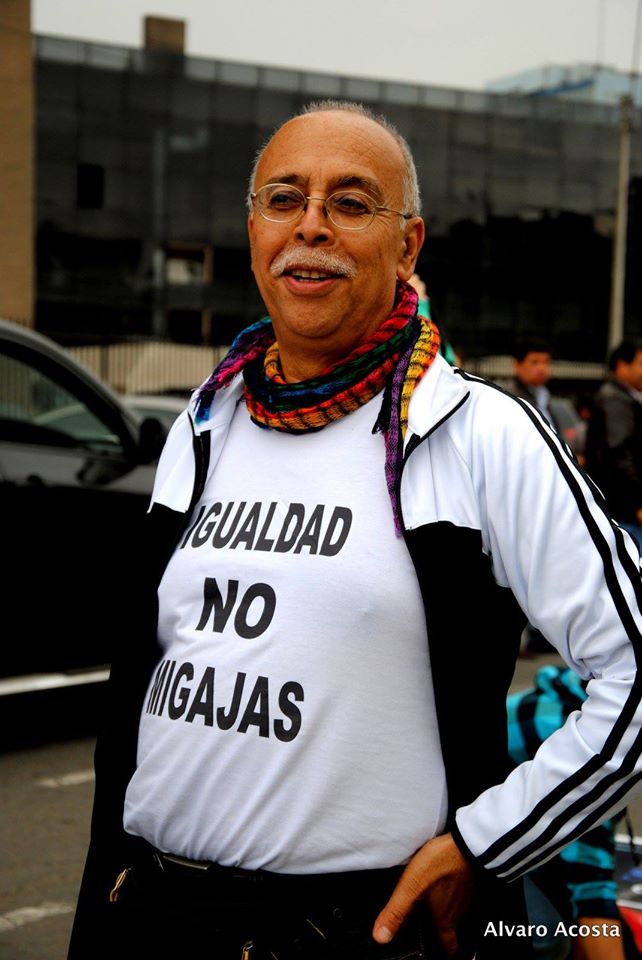

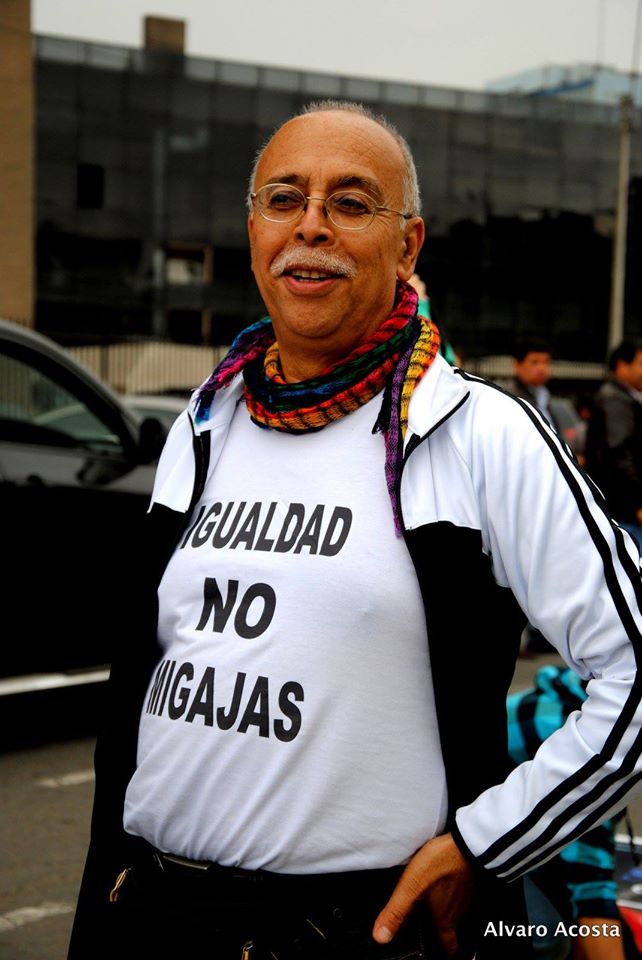

Edgardo Corts lives in Buenos Aires, and is a founding member of the organization Mayores en la Diversidad and the Frente de Personas Mayores, and is vice president of the Centro de Jubilados y Pensionados de ATE Capital.

“ The situation of older people in Argentina is characterized by their invisibility . In general, when older adults leave the workforce, we enter a cone of invisibility where society begins to call us “grandparents.” We defend our role as old people, and we leave the title of grandparents for our grandchildren.”

In the social sphere, we don't develop the role of grandparents; we develop it within family spaces. Older adults are considered subjects of care, and in reality, we are subjects of care just like anyone else in society. All individuals, all of society, are subjects of care. We are placed in this position and removed from the position of political subjects.

The greatest struggle for older people, and especially for the LGBTI+ community, has been to become political subjects . And as such, to be able to fight against the various circumstances we face, among the most fundamental being stigma and discrimination. These are barriers that have prevented us from making progress in HIV prevention, and that have also delayed us from achieving marriage equality or the Gender Identity Law.

[READ ALSO: A home for LGBT+ seniors: “We no longer want to be invisible” ]

In Argentina, there has been legal progress, but society has not yet fully embraced these rights. Regarding older adults, our work is to make ourselves visible both within and outside the LGBT community. In my case, for now, I am a survivor of two pandemics: HIV and Covid-19. The first put me in the spotlight for being gay, and right now, Covid-19 puts me in the spotlight for being an older adult living with the virus and other health issues.

As a general and cross-cutting resistance movement of older people, we continue to demand that the State and its agencies, as well as social organizations, recognize and value us as political actors and allow us to participate in the creation of public policies. Regarding HIV, we seek the renewal and creation of a new HIV and STIs law, because the current law is over 30 years old, and especially after this pandemic, we believe it needs to be revised. The National Front for the Health of People Living with HIV is already beginning to mobilize, even if only through social media. The other issue we pursue and fight for is a cure for HIV and AIDS.

There are populations far more vulnerable than the gay and lesbian community. Trans people face greater stigma and discrimination. Their standard of living is often informal, and by age 40, they can already be considered elderly due to their life expectancy.

"The lockdown has helped me to open up my inner self."

Agustín Núñez is a Paraguayan actor, director, and playwright. He is 73 years old and from Villarrica. Last year, he celebrated half a century of artistic life in the country. He lived in Colombia for a time and, after the fall of the Stroessner regime, returned to Paraguay. He took over as director of the Municipal School of Dramatic Arts and founded El Estudio, Paraguay's first acting and directing school. A week ago, he announced that, due to the pandemic, he had to leave El Estudio, the institution where many actors, actresses, and directors trained.

“This time of confinement has allowed me to open up, to connect with a part of myself that was perhaps neglected, dormant due to the neurotic routine of daily life. It helped me realize the true value of things and people. That we can live with much less than what consumerism tells us and value people, both near and far, in other countries, in a different way because of their closeness, their concern, and the constant help they offer. I allowed myself to experience a mythical time, a time without clocks, without calendars. There's a Japanese saying that happiness consists of eating when you're hungry and sleeping when you're tired. I think it's wise, although it's very difficult to do so within our work and social obligations.”

This pandemic is forcing us to be creative, to develop patience, and to re-evaluate our values. It has greatly strengthened our sense of solidarity and identity . It has made us realize, more than ever, that it is not snipers who win battles, but armies. To the extent that we stand together, identify with one another, and share a common vision, things can improve significantly.

If we didn't exist for the State before the pandemic, we exist even less now. All the territory we've gained has been won with blood, sweat, and tears, and that's something I greatly value about our community. We must continue fighting for our presence, our respect, our rights; break down countless myths and taboos deeply rooted in our culture; and never lose hope or our fighting spirit.

I'm extremely sensitive right now. I had to leave my teaching position due to financial reasons, because of the pandemic. It was very painful but also very valuable because it showed me the solidarity of so many people in the country and abroad. Nevertheless, it was a very hard blow. We have to come out of this as a better version of what we were doing; we can't continue as we were. I have a phrase for the stage and for life: "We have to transform all our flaws into strengths."

"I want to use words to bring light to people."

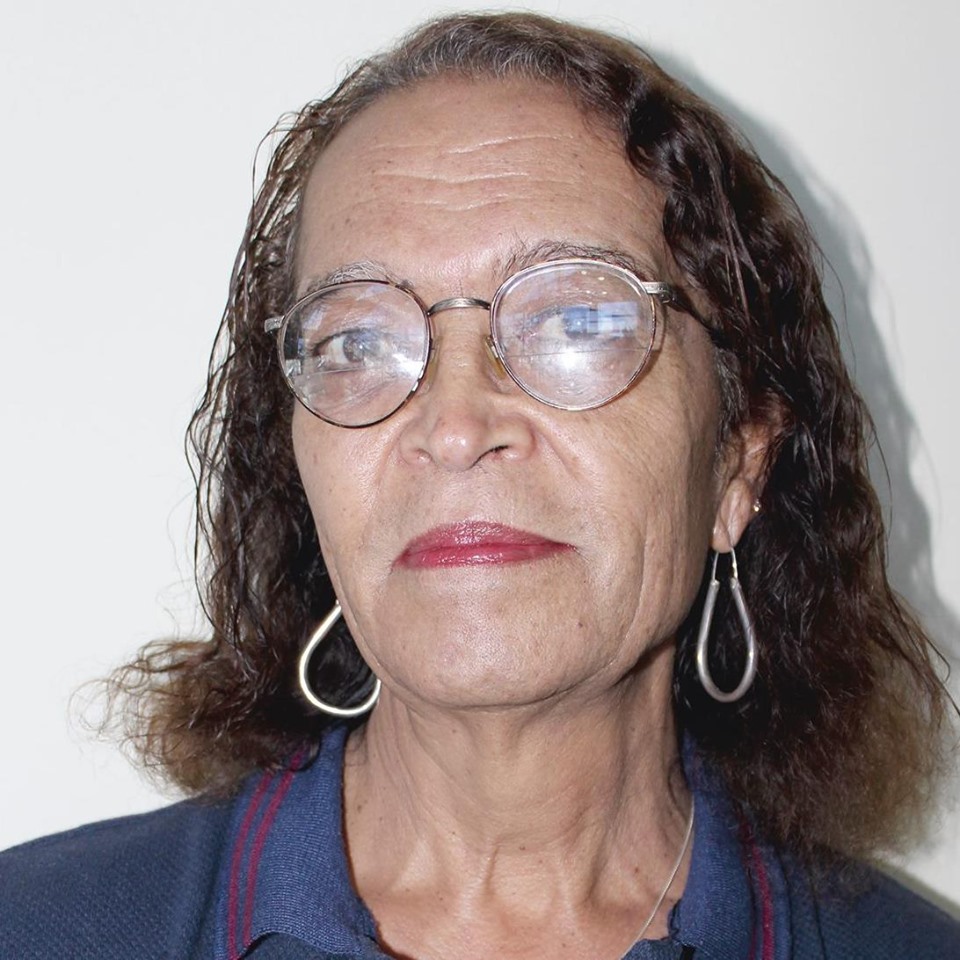

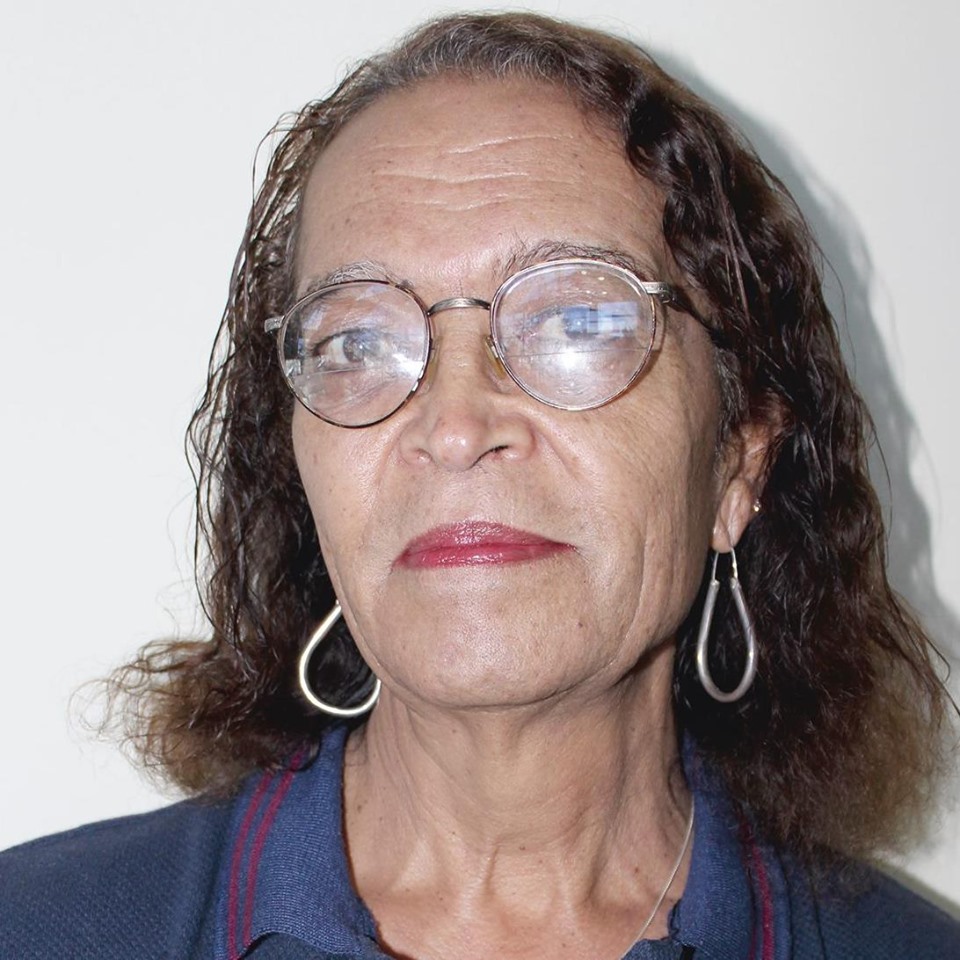

Norma Castillo is a long-time activist for LGBT+ rights in Argentina. In the 1970s, while living in Colombia, she met Ramona “Cachita” Arévalo, a Uruguayan woman who was also in exile. In 2010, after 30 years together and advocating for lesbian rights, they married, becoming the first same-sex marriage in Latin America. In 2015, Norma was declared an Outstanding Human Rights Figure of the City of Buenos Aires. Cachita passed away in 2018.

“Coming from the post-war era, I never expected this war. Quarantine isn't difficult for me. It's very hard, but in general, isolation and exclusion are nothing new for older people. We campaigned a lot, but the issue of older lesbians is quite new. That's where our open struggle began, and there are so many taboos; it's astonishing. In the era when we were born, doctors said we lost our sex drive with menopause. That didn't stop me from wanting to dismantle all the lies I discovered as I grew up. There are many older people who were left frustrated with their feelings, with the society that stifled them. My identity was changed through words, and I want to use words to shed light on people who don't dare to speak out and who live false lives, doing things in secret.”

"Without money and in poor health"

Paty Conde has been living on the streets of San Salvador for 66 years. She is one of the survivors of a massacre committed by state security forces against the trans population during the armed conflict (1980-1992). Now she continues to resist poverty, precariousness, and the uncertainty caused by the coronavirus crisis.

She has lived since 2003 in an impoverished boarding house in the historic center of the capital, paying $90 a month for her room. Before the pandemic, she sold sweets, bread, and various hygiene products. Her meager earnings have now dwindled to zero due to the city's lockdown implemented by the mayor's office to try to contain the spread of the virus.

“I’ve lived here since 2003 and I’ve never experienced anything like this. I’ve been feeling unwell, with the flu, and I can’t even go out to see a doctor. I used to sell sodas, earning about 15 or 20 dollars a day. Now I don’t sell anything because no one comes by. I’ve run out of money because the lady from the counter came and I had to pay the hundred dollars I had saved. I just want all this to be over, I can’t take it anymore. I feel sick and bored,” Paty told Presentes.

The Salvadoran State has no record of the LGBTI population, therefore it cannot design specific public policies that address the main needs and demands of people who, like Paty, must find their own way of surviving in the midst of calamity.

"These times will leave lessons and learning experiences."

Jaime Lorca is Chilean, 70 years old, and a member of Acción Gay, an organization that has been fighting for HIV prevention and supporting people living with the virus for 30 years.

"I live alone and it's been very hard. At work, we suspended operations on March 16th and were all sent home. In my case, it's more complicated because I live with HIV and I'm elderly. That scared me a lot in the first few days. Later, with the lockdown, I gradually calmed down because I'm alone in my house and no one has been here for 75 days; the risk of infection is minimal."

The first few days I tried to distract myself by reading novels. I don't read as much now. I avoid watching the news because it makes me anxious, and when I get anxious, the weight of loneliness sets in. It's a physical loneliness, because I'm fortunate to belong to a very close-knit family. We're a very strong clan; they can't come to see me, but they keep me company from afar. Every night we have video calls with my siblings and nephews. I think about the people who don't have family or loved ones to turn to right now. It must be much more painful for them; I don't know what I would do without that support.

This pandemic has made people think about the future , about what it will be like. But even though I haven't worried about that for a while, I think the coming months will be very complex. Twenty-two years ago, when I was diagnosed with HIV, I stopped making plans. Since then, I live day by day; I don't plan things more than three or four days in advance. Before, people were dying; making plans wasn't feasible. That's how I got used to living, and that's why it's hard for me to think about the future.

These times will leave us with many lessons and insights. I've had to learn countless things I never thought I'd do. For example, work meetings via Zoom, because I follow up with people living with HIV to make sure they're doing well and keeping up with their treatment. It took me six hours to learn how to use it, but I managed. I also had to learn how to use a credit card to buy groceries and food online. For a 70-year-old, that kind of technology is very complicated.

The actions of young people these days will also teach us lessons. In Chile, with total lockdowns and curfews, massive clandestine parties have been reported. Recently, one with 400 people was broken up; I find it outrageous to risk lives unnecessarily. I would like them to become aware of the harm they are doing to us all by not respecting the guidelines issued by the government.

Chile is going through a very significant crisis right now: in October we had an unprecedented social uprising because there is a complete lack of faith in politics and institutions. Young people took to the streets and now they want to continue. I believe this is not the time, because it would expose us to this new pandemic. The time will come to return to the streets to continue making the necessary demands. However, we must keep the discussion alive, so that everything that October sparked doesn't fade away . So I propose that you unleash your creativity and use the internet to express and communicate your discontent with the Chilean system. Social media today is like our lifeline, and I believe we can use it for something truly important.

"We consider ourselves victorious"

Manolo Forno is 66 years old and one of the founders of the Lima Homosexual Movement, along with his friends. It was in 1983, in the months leading up to the outbreak of an epidemic that would mark the lives of thousands of gay activists, that they began to find the courage to organize and go out into the world. From that day, 37 years ago, when a dozen future young activists met at his house in Punta Negra to draft the first statement and publicly declare that they were homosexual, to these times when he cannot go out in the streets and physical contact is once again forbidden, he reflects on these times.

"It's very clear that we are high-risk individuals. I am 66 years old, diabetic, hypertensive, and I had pneumonia last year. I haven't even left my house since March. I live with my husband, the only person who comes and goes, following strict hygiene protocols to avoid infecting me."

The other issue is that, although I retired through the AFP (Pension Fund Administrators), since I'm not considered part of a family, according to this government, I haven't received anything. Even though I live in a middle-class neighborhood, I have no access to any source of income. I've become completely dependent on what my partner can give me. This has created limitations in our lives; now we have to think about expenses for two people, and I can't contribute a single penny because I'm not eligible for a bonus. Besides, we have to pay double for all our health and insurance costs. He has insurance, he pays, and his wife can get treatment, but I can't .

I wonder how long I'll have to stay indoors before I feel safe enough not to get infected. Until a vaccine is available, I'll have to remain locked up. This is causing me anxiety. Even though I have a 99% chance of not getting infected, I have to take countless precautions that, instead of making me feel relaxed, are causing me stress.

The future for me is staying home, unless I decide to go out and say "screw it all." The other option is waiting for a vaccine and an effective treatment. My whole world has been reduced to watching reality from my window.

I live in an apartment, and if I want, I can lock myself in my room, but I think about the people who live in just one room, and it makes me feel bad. I think about the young people who lost their jobs and have to return to oppressive family homes, where there is violence. I think about some lesbians, how the manipulation and control against them will increase with the monitoring of their phones and communications; they will be under even more surveillance. In the case of children and teenagers, situations of abuse are increasing at home, and although schools have closed and bullying has therefore "disappeared," violence and sexual abuse in their immediate environment will increase.

How do we channel that anguish, that oppression? We need to find ways to visible in the media , so people know what's happening to us. People might think it's all about bonuses, about money, but there's more to it than that.

On a positive note: living together with my partner in a shared space during March, April, and May has helped us manage our relationship and smooth over any lingering issues. We currently consider ourselves victorious; we've been able to move forward as a couple without violence, despite disagreements, and ultimately reaching agreements.

In activism, we are finding new ways to carry out advocacy actions, defining new strategies, new ways to connect , since Covid has taken away our ability to socialize in person. Now the fight is waged through the phone, WhatsApp, the computer, Zoom. The fight continues until final victory.

All our content is freely accessible. To continue producing independent, inclusive, and rigorous journalism, we need your help. You can contribute here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.