Midwife, trans and Mapuche: how to survive discrimination and bring life into the world amid the pandemic

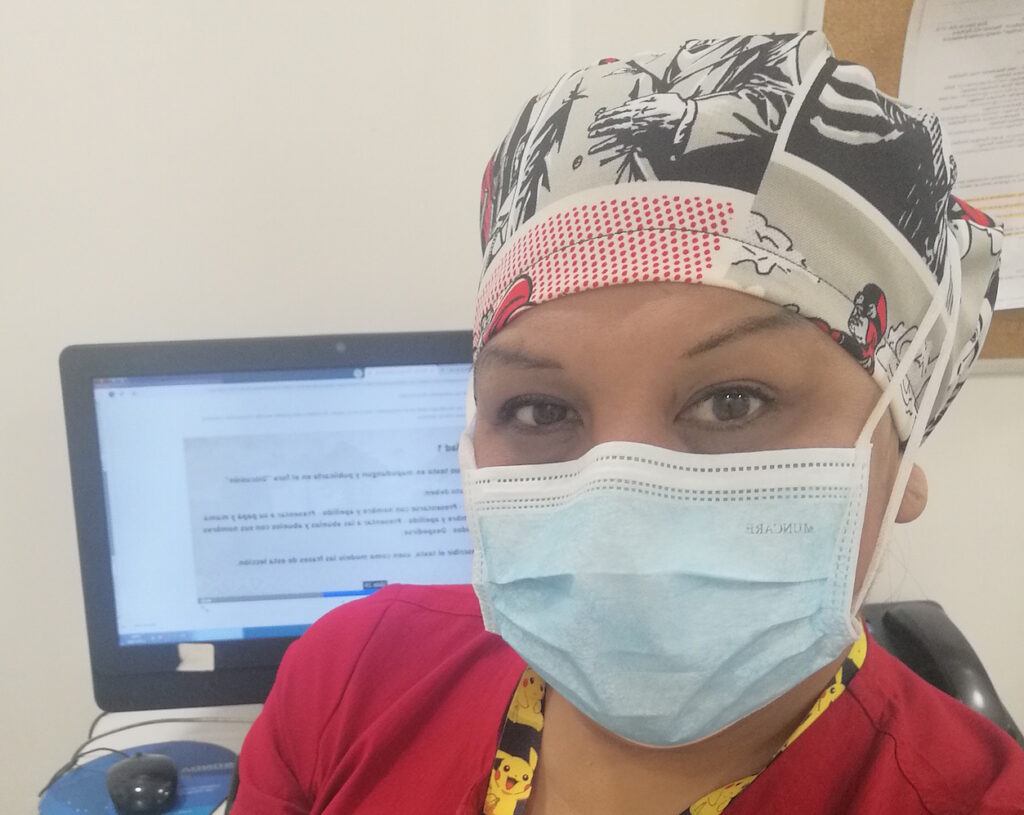

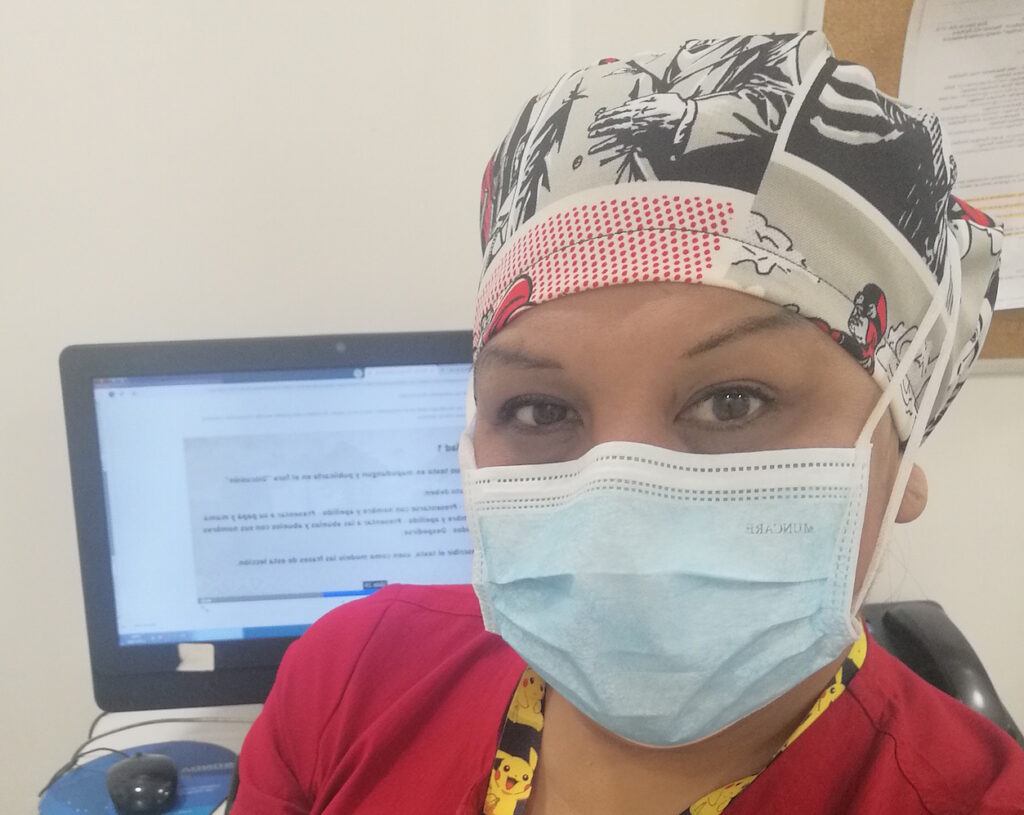

Claudia Ancapán Quilape is a 44-year-old trans woman, midwife, Mapuche and survivor, who has worked in a clinic in Santiago for several years.

Share

By Airam Fernández, from Santiago, Chile

Photos: Josean Rivera/Presentes Archive

A round of applause took her completely by surprise. It could be heard outside her house, but it seemed very close. Claudia Ancapán Quilape wasn't expecting it, but the applause on the night of April 7th was for her: a 44-year-old trans woman, a midwife, Mapuche, and a survivor, who has worked for several years in a clinic in Santiago and where today, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, she continues to assist in births, cesarean sections, perform gynecological checkups, monitor pregnancies and gestational illnesses, among other tasks typical of obstetrics and childcare, the field she studied.

That night, some of her neighbors replicated the scene of gratitude toward the healthcare professionals battling on the front lines, a custom that began in Italy and spread to many countries, in line with the virus's global expansion. Claudia had to go outside to confirm what she was hearing. She says she couldn't believe it.

"Bravo, Claudia, bravo!" they shouted from a balcony. "We were waiting for you, neighbor, you deserve all the applause."

"Thank you so much..." Claudia paused, looked around, then stared upwards for a moment, smiling. "Thank you all."

She'll never forget that, she tells Presentes. No one had applauded her like that, in public, since she decided to transition in 2005. Not even when she presented her thesis, which allowed her to graduate with honors after a long investigation into trans people, sex work, sexually transmitted infections, and healthcare services at the Austral University of Chile, where she began studying under her biological identity.

[READ ALSO: Survey reveals increase in homo/transphobia in Chile in the context of Covid-19 ]

And now, she least expected it from her neighbors. Until recently, she faced some uncomfortable moments and attempts at discrimination in her own community. Claudia says she's used to it by now, after so many hardships she's endured in life. But this time it wasn't because of her identity or her roots, but because of her profession. It coincided with the complaints made by the Chilean Medical Association in early April about discriminatory measures being taken in some buildings against healthcare workers, restricting their use of elevators and common areas, and requiring them to take care of their own trash, among other things.

“The first few days I had to educate my community. There was a lot of fear, and I had some disagreements with one neighbor in particular. He questioned my role, but out of panic. And although I understood his reaction, I felt compelled to stop him. I convinced him to listen to me and explained all the safety measures I take every day when leaving my house, at work, and when returning. I had to talk to everyone about this and make them understand that if the healthcare staff doesn't do the job, who else will?” Claudia says over the phone on a Monday while resting at home after returning from a 24-hour shift at the clinic.

Evangelical family and indigenous origins

Her life wasn't easy, like most trans people. She was born in Santiago, but her childhood was spent in towns in southern Chile. She grew up during Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship, in an evangelical environment and in a family of Indigenous origin . She is the second youngest of six siblings, attended a rural school, a public school, and later, despite the religion practiced at home, a Catholic school in Puerto Montt, one of the cities that symbolizes German colonization in Chile.

“That was a very aspirational, status-driven decision, because in Chile, unfortunately, it’s very common for school to be key to your professional future. In that Catholic school, there was a lot of whitewashing, and I was a black mark. But I dedicated myself to studying and getting the best grades so that no one could criticize me or point me out for anything else,” Claudia recounts.

At five years old, she had her first encounter with her gender identity. She doesn't remember it, but she knows about it from what her mother told her years later. “I wanted to be constantly surrounded by girls, playing with dolls, always in contact with the strength of my mother and my sisters, because I felt more comfortable on that side of the gender spectrum. I also wanted to have long hair, like Dorothy Gale from The Wizard of Oz, but they gave me military-style haircuts because under the dictatorship all boys had to have their hair like that,” she says. She had anxiety attacks, panic attacks, and some bouts of anorexia from a very young age. And although her parents took her to many doctors, none of them understood what was happening to her. “I suffered a lot because I wanted to be a girl and I couldn't. At that time, there was a complete lack of knowledge about these issues,” she recalls.

She decided to study obstetrics because she suspected what was happening to her, but she didn't have much information. In a couple of books she found in a public library, she read that in other countries something called sex reassignment surgery existed. That discovery was one of her first guiding lights, helping her to stay on the path and not give up.

“Knowledge was my salvation. I decided that if I wasn't going to have access to specialists, because at that time it was unthinkable, then I would approach science myself, and for that I had to specialize in this area of health, to understand my own anatomy ,” she says. She took the opportunity to study hormones extensively and made her body available for clinical studies.

Violence and discrimination

At university, she experienced numerous episodes of physical and institutional violence, as well as discrimination. Shortly before graduating, a group of neo-Nazis attacked her in the same way that a similar group would attack Daniel Zamudio years later in Santiago. They beat her until her face was disfigured. They also raped her. “It was very hard to overcome that episode, but I always say that it was a lapse in my life that ultimately only made me stronger. Those who did that to me didn't win, because they didn't kill me; they only pushed me to achieve something that seemed impossible: for a trans woman to graduate as a midwife in a country as backward and patriarchal as Chile.”

Years after working at several hospitals in the south, Claudia moved to Santiago, but no one wanted to hire her after she was fired from San Borja Hospital. She dreamed of building a career in the maternity ward of that public health center. Since she was turned away from all the hospitals and clinics in the city, she spent three years making ends meet with various jobs, mostly in the fast-food industry.

The death of her father in 2007 was one of the final pushes that led her to decide to live "full time" and abandon the double life she says she led before transitioning. And it affected not so much her family as the medical community and her close professional circle. "For the professional circles I moved in, it was an insult. They told me that this would destroy my credibility when it came to work, because being transgender was associated with prostitution . That still happens to me to this day. Once, while I was looking for a job, a doctor told me that what I had was a mental illness and that I would never be able to practice medicine again," she recalls.

“What inspires me most about the Mapuche cause is their resistance.”

Claudia is a resilient person, partly because of all the obstacles she has had to overcome. “I have a strong character, the character of a woman who has survived violence in all its forms,” she says. But she is also convinced that her Mapuche roots have a lot to do with how she has faced life's challenges and gotten to where she is today. “Many times I have been discriminated against simply because of how I look, because it's obvious that I have Indigenous roots. For me, the discrimination has always been twofold ,” she adds. This makes her feel even more proud of her origins, her family, and her community.

She often attends March 8th marches or diversity demonstrations wearing something traditional to her people, like the Wenüfoye flag. Once, she went to a Pride march with a sign that read, in Mapudungun: “Your freedom will be real when you manage to let go of the burden you don't need.” She was dressed in a quetpám, a sikil brooch hanging on her chest, and a trarilonko on her head, at forehead level.

Even so, Claudia acknowledges that her connection to the Indigenous cause isn't as deep as she'd like, and she regrets not having learned the language as a child, when she listened to her mother speak. As an adult, she's taken several courses, the most recent being online. Meanwhile, she's studying the coronavirus, as the curve in Chile continues to rise, surpassing 10,000 cases.

“What inspires me most about the Mapuche cause is their resistance, how they fought against the conquerors, how they care for their lands and the entire ecosystem,” Claudia confesses about this people who have faced discrimination in many ways in their country for years. A recent study by the University of Talca on racial discrimination in Chile revealed that most Chileans prefer to distance themselves from any Indigenous connection and believe that having a Mapuche surname can be detrimental when seeking employment or promotion. Claudia says that this reality breaks her heart.

[READ ALSO: The trans nurse facing the pandemic: “We need the job quota law” ]

This year, she had planned to travel south to immerse herself in an Indigenous community to learn more about them, and about herself, through everyday life rather than from books, academia, or family history. But the coronavirus changed her course and priorities. For now, Claudia remains in Santiago working, attending to emergencies, and assisting doctors in operating rooms. On her social media and with her close circle, she shares useful information that can help prevent infections. Every time she gets home, the routine is the same: she takes off her clothes before entering, puts them in a bag to wash immediately, showers, disinfects everything she touched, cleans the bathroom, and so on, every day, very aware of each step she takes: “I am vulnerable, and I won't deny that I sometimes feel afraid, but I do everything I can to protect myself and my community. This is the role I've been given, and I'm grateful to life for it.”

All our content is freely accessible. To continue producing inclusive and rigorous journalism, we need your help. You can contribute here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.