The revolution of the genre: repercussions of a historic cover

Avery Jackson, a nine-year-old transgender girl, graces the cover of the January issue of National Geographic magazine. The edition, dedicated to gender issues, sparked both praise and controversy. How do people involved with transgender children view this cover?

Share

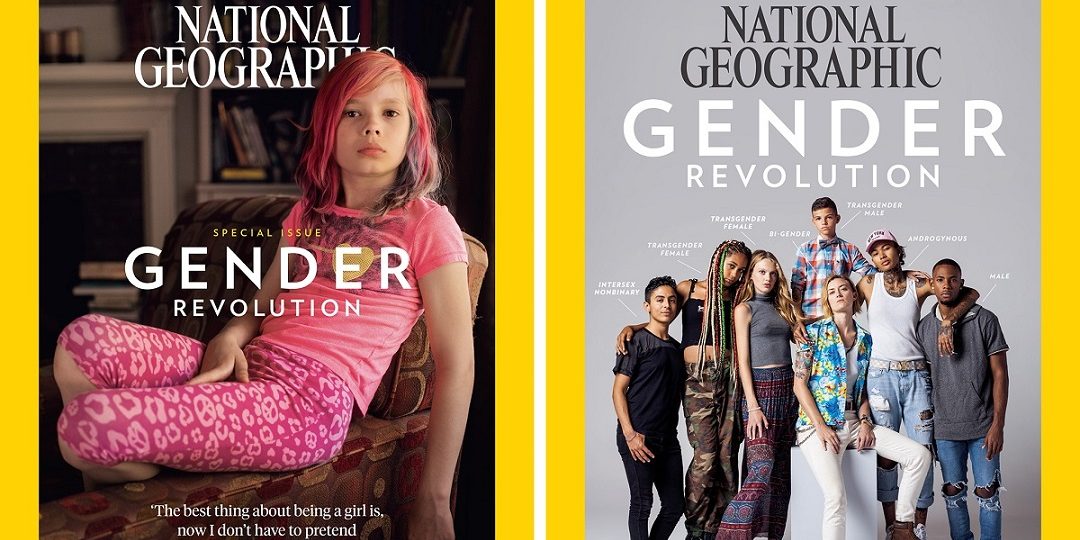

Avery Jackson, a nine-year-old trans girl, graces the cover of National Geographic's January issue. The edition, dedicated to the theme of gender, sparked both praise and controversy. Presentes wanted to know how people involved with trans children view this cover. For its first issue of the year, "The Gender Revolution," National Geographic interviewed 80 nine-year-old children in eight countries across different continents. They photographed them and asked the same questions, all focused on one central issue: what role does gender play in their lives? Of those eighty portraits, Avery Jackson's—a transgender girl from Kansas, USA—became the magazine's cover story. The cover, in addition to a striking photograph, included Avery's testimony: "The best thing about being a girl is that I don't have to pretend to be a boy anymore." The promotional announcement for the issue immediately ignited such controversy that the online version published an article to address the comments. "We dedicated an entire issue to what we call 'the gender revolution' at a time when humanity's ideas about gender are changing, and we wanted to explore and explain them," said Susan Goldberg, the editor-in-chief.

"Trans children don't always want that ideal appearance"

“I think it’s excellent that this reality is being acknowledged and promoted,” said Niki Raveau, director of the Transitar Foundation (Chile). “Dressing the girl in pink and using a very feminine image falls into a cliché. It’s even more revolutionary to know that trans children also take time to transition, and that they don’t necessarily achieve an ideal appearance or don’t always desire that ‘ideal’ appearance that goes from one end of the binary to the other (male to female, female to male),” she told Presentes. Robin Hammond is the National Geographic photographer who photographed Avery before knowing she would become the cover star. Hammond, in an article in the digital version, explained the details. He recounted that when he arrived at Avery’s house, he found her dressed like that: “What you saw in the photograph is what she was wearing when I arrived. I didn’t ask her to dress like that,” he responded to the thousands of comments that emphasized this point. “Some transgender people prefer to dress that way because they feel it better represents their identity.” "It's a way of communicating who they are to a world that often doesn't accept them," he said in the note where the magazine responded to the comments raised by the cover.#PutYourselfInMyShoes

The director of the Transitar Foundation believes that the most revolutionary aspect of trans children lies far from their appearance: “They have so much to say, so many ideas. It’s their ideas, expressions, and desires that truly revolutionize things, not their outward appearance.” With these ideas in mind, the municipality of Providencia (through the Department of Diversity and Non-Discrimination) and the Transitar Foundation developed the video #PutYourselfInMyShoes, where children demand their rights without conforming to the “ideal appearance.” [embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOLb93NMmx0[/embed] Niki recalls recently watching an interview with a trans girl on Basque television. “The conversation focused solely on the difficulty of being ‘accepted’ and aligning the external with the internal feeling. I find Selenna’s (the Chilean girl who transitioned at the earliest age) statement when she’s about to marry Kevin (a trans boy from the Foundation) to be more revolutionary, relevant, and realistic.” We say, "Okay, that's lovely, we're on the spectrum of the bride in white and the groom in a black suit." Then Selenna adds, "But Kevin's going to have babies." Those few lines break with the prevailing ideas of motherhood, fatherhood, genitalia, and family. Selenna's proposal becomes a new model for building community. That's the kind of idea I'd like to see highlighted."People who support this fight don't need to see Lulu's face."

Lulu is the same age as Avery and lives in Argentina. A few years ago, her mother, Gabriela Mansilla, saw a documentary about another transgender girl from the United States, Josey Romero, also produced by National Geographic, and began to see her daughter's story in a different light. "It was like being run over by a bulldozer. That's when I understood that she was a trans girl, that her identity was that of a girl. I cried for twenty days. And then I reacted." “I told myself: if she wants to be a princess, I’m going to help her,” Gabriela told journalist Mariana Carbajal in 2013, in an article published in Página/12. Lulu is a made-up name to protect the identity of the girl who, at age 6 (in October 2013), received a new birth certificate and an ID card with her self-perceived identity without going through the courts. It was considered the first case of its kind in the world. For the past few days, many people have commented to her mother about the Avery magazine cover. “I don’t agree with showing children’s faces,” Gabriela told Presentes, clarifying that she didn’t spend much time looking at the cover. “While everything depends on the country, the context, and the intentions, it would be better not to expose children like that; you never know the repercussions, good or bad, it might have. Even today, I receive congratulations in the street, and also people who ask me how I do this to my son.” Gabriela says that “it’s one thing to bring up the issue for something that One thing is to achieve, and another is unnecessary overexposure. History can always help others, but not the exposure of children. And it is we adults who should ensure they have a normal childhood. Appearing on a magazine cover doesn't seem to help in that sense,” Gabriela pointed out. She clarified that she does support and value initiatives like the video about transgender children made in Chile, an initiative she appreciates because she believes children there are not overexposed. For years, media outlets from various countries around the world have asked her for a photo of her daughter. The mother—who raises Lulú and her brother alone because their father abandoned them—refuses. “If it's difficult for me to handle media harassment at times, I can't imagine what it must be like for a child. What I do know is that you will never find Lulú's face in any media outlet. She doesn't have to be a phenomenon; she has to be able to live in the present without being pointed at in the street. That's why my daughter's photos are among the people who love her.” She was convinced: "People who support this fight don't need to see Lulu's face to believe in this free, happy, healthy childhood. You don't need to see to respect, or to see to believe."Who is the girl on the cover?

Avery Jackson lived the first four years of her life as a boy. She was an activist long before appearing on this cover. In February 2014, a profile published by the Kansas City Star featured a conversation Avery had at age six with Caroline Gibbs, a therapist and the director of the Missouri Transgender Institute. “Could you tell me something about yourself? Are you a girl or a boy?” Gibbs asked. “I’m a girl,” Avery replied. “What makes you think that?” “Just that I am.” “Does it have to do with clothes or games?” “No. Just that I’m a girl.” At seven, Avery recorded a video that went viral on social media, telling her story: “When I was born, the doctors said I was a boy, but I knew in my heart I was a girl. My body has some male parts, but that’s not wrong, that’s okay. It’s really hard not being able to be yourself, and I was a girl,” the girl says, looking into the camera. "There are people I don't understand, people who are afraid of what's different." She asks, "Who cares about the parts of my body? Do you walk around naked? It's hard being transgender, but today I'm proud of who I am, because I'm transgender and I'm a woman. And I'm a normal girl, a normal transgender girl." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUN75MGqdpUWe are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

Excellent article and excellent publication. Keep it up, congratulations!

Whether it's because society understands it, or by force, because it's becoming more visible (as in this case), transsexuality, transgender identity, is going to be a reality for many more people than it currently is. And I'm glad that's the case.

The world is changing, there's resistance, but that won't stop us from moving towards a world where many worlds fit.