Daniel Nizcub: "Writing poetry was part of my transition"

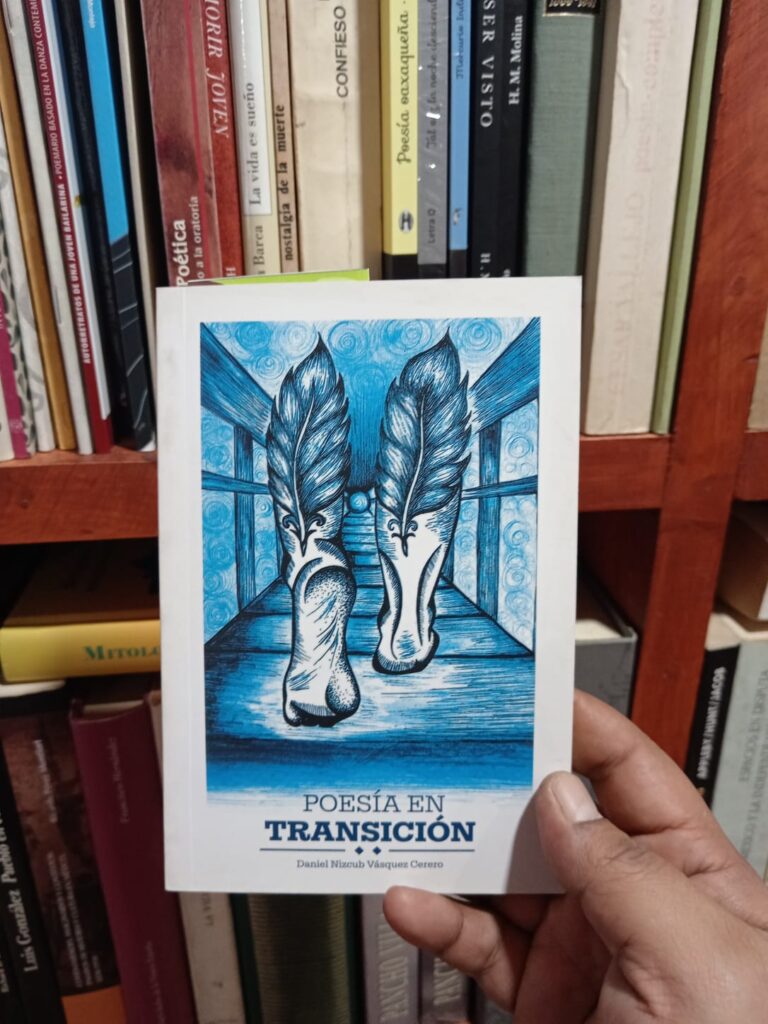

Daniel Nizcub is a poet, cultural manager, and radio host from Oaxaca. "My greatest dream is that no one else experiences a transition in solitude," he says about his poetry collection, Poetry in Transition.

Share

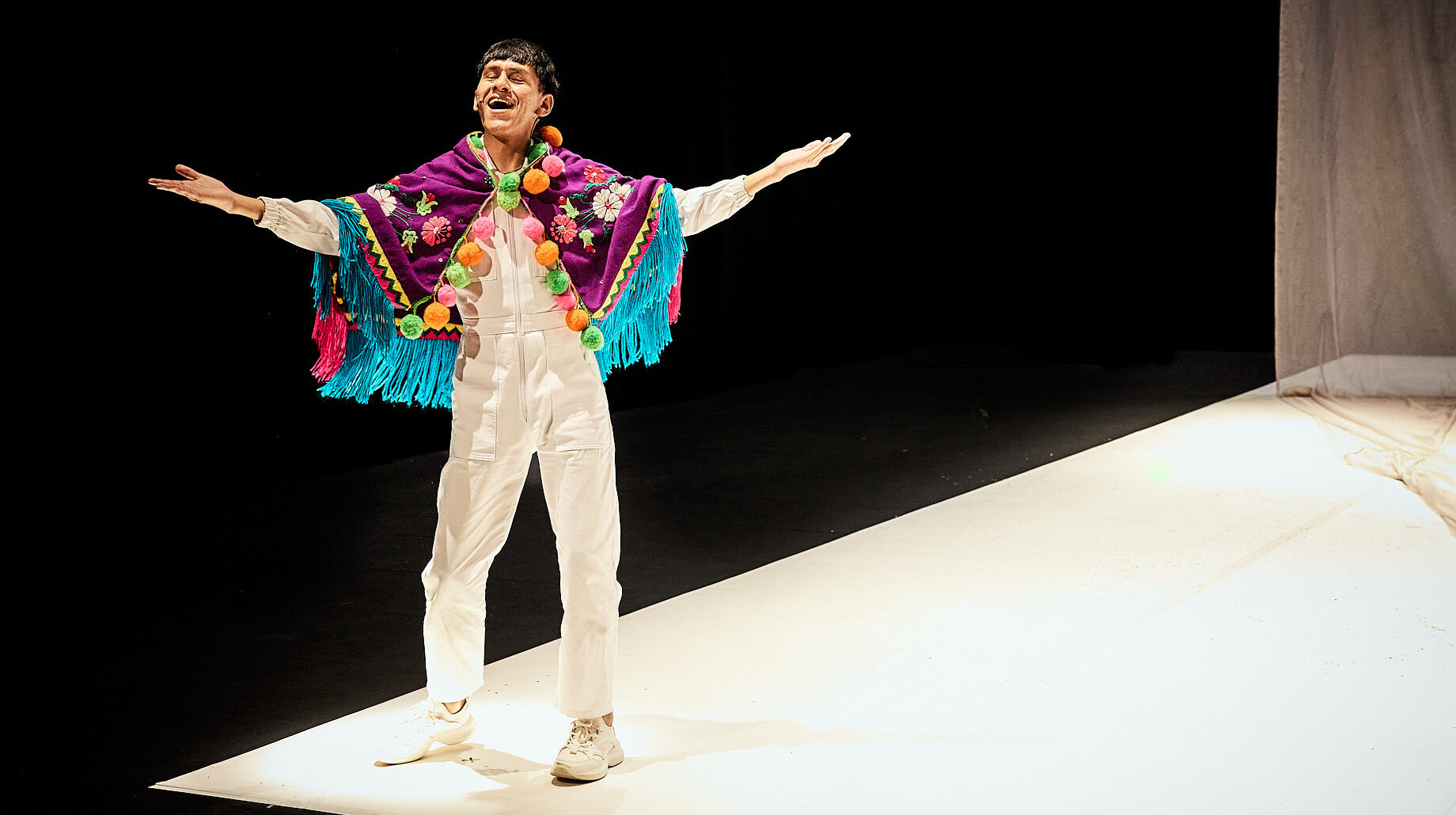

Daniel Nizcub is a poet, cultural manager, and radio host from Oaxaca. Born into a family with Mixtec and Zapotec roots, Daniel grew up constantly moving between Mexico City and Zaachila. This daily migration shaped his identity and artistic sensibility. His work and life are marked by what he calls "inhabited dualities."

Daniel began writing as a way to name the pain and loneliness he felt in 2010, when he couldn't find any transmasculine role models in Oaxaca. His poetry collection, * Poesía en transición * ( available for free online ), is a bridge to support other trans men/transmasculine individuals and ensure that no one else experiences this journey alone.

With a career in community radio that began in 2006, one of his biggest fears when starting hormone therapy was losing his "radio voice." That voice would later lead him to be recognized with the third honorable mention in the sound art category at the 2025 Radio Biennial. There, he presented a poetic dialogue between his current voice and a letter he had recorded himself ten years earlier.

For Daniel, poetry is not only in books, but in the daily life of his people, in the hills and in the figure of his grandmother, whom he defines as the ultimate expression of poetry.

In projects like “ Oaxaca Trans: Life Stories,” he dedicated himself to telling the stories of trans people living in different regions of the state, combating centralism and cultural extractivism, using interviews, chronicles, and poetry written by themselves as forms of expression. Daniel has also participated in Cono de Luz, an anthology that brings together texts by queer people from Latin America.

She is working on self-managing the third edition of her poetry collection and her future goal is to create a space to publish other trans authors and continue to claim the right of trans people to tell their own stories without intermediaries.

-Do you remember your first encounter with poetry?

I was privileged that my father owned an anthology of Atahualpa Yupanqui, this Argentine troubadour who wrote so much about the countryside and the land. I didn't know exactly what poetry was, but what I felt was that what he wrote reminded me of my home, Zaachila: the stones, the paths, the roosters, the hills, my grandmother. I was so moved to be able to understand those words; as a child, I told my sister that once I learned to read, I would never be able to stop.

For me, poetry is something you physically feel in a place you didn't know existed within you; it's like you're rediscovering the world, and even if you're talking about a tree you've seen a thousand times, poetry tells you about it in a way that feels new. It's difficult to say what poetry is for me, because it's more about something I feel in my body.

-You've spoken to me about the "dualities" that inhabit you. How did your migration history between Ciudad Neza (a municipality on the outskirts of Mexico City) and Oaxaca shape your approach to writing?

Migration has been a part of my life since birth. I grew up in a context where my parents were in Mexico City but longed to be here; they instilled in me a deep longing for my hometown. I grew up between Ciudad Neza and Jardín Balbuena, and when I came to Oaxaca, it was the same routine: going back and forth to Zaachila (Oaxaca). These dualities are ingrained in me: knowing how to navigate the city and the subway, but also the traditions of the calenda and the town festival. When I arrived in Oaxaca as a teenager, it was a revolution: going from that enormous city to a place where everyone is watching you, where everyone is your aunt or cousin and already knows your life story. In that culture shock, when I realized I liked girls, my gender identity, what I did was write and keep quiet. I was very quiet, I just wrote.

That's why I write. When something compels me to write, I feel a tightness, a knot, as if something is wrong inside me. If I don't write, it's like feeling like my body is sick.

-Did your first poetry collection, Poetry in Transition, stem from that vital need to write? How did it come about?

I wrote about love and my identity because it hurt, and I didn't know how to name it. In 2010, I didn't know what 'trans' meant; I didn't have anyone in Oaxaca to ask which endocrinologist to see. I only had a few kids from YouTube on my screen. My poetry collection didn't start as a project in itself, but rather when I realized I was living what was happening and it hurt. I would write a poem like those trans kids who record their voices every month while on testosterone and upload them to YouTube. Before I knew it, I had a group of poems that expressed fears I hadn't even noticed. Writing and writing poetry was part of my transition itself: it was a way of recognizing myself, of letting go, and above all, of dissolving into places other than pain.

-In your work as a manager, you promoted Oaxaca Trans . Why is it important for trans people to write their history?

"It's essential that we have spaces managed by ourselves. A cis editor's perspective is not the same as a trans editor's: what kind of readings will they see? What will they focus on? In Oaxaca Trans , my role was to find people, because we all thought we were alone, each on our own little corner. We created a network so that people know there are more trans people in Oaxaca , not just the one who appeared in the newspaper, for example. It's important that they write in their own words because it's a story that no one else will interpret for them. It's time to speak out."

-I notice a close relationship between trans people and poetry. What does poetry offer trans people?

I think poetry is one of the most tranquil, quietest, yet simultaneously loudest and safest places we can inhabit. Because I see it this way, unlike theater or dance, which involve showing our bodies, putting them on display, exposing them. In writing, this doesn't happen explicitly. And even in writing, we can be whoever we want without that requirement to show our physical bodies. We can also create our own universes, understand each other, and create a constant dialogue. I think that's why, because of the many silences. Poetry, or writing, is something we have close at hand now with our cell phones. I like to write by hand and I carry a notebook with me everywhere, where I write simply for the pleasure of it, not with any need to create a poem. Poetry is also a way to connect with each other. In my experience, it has been a way to accompany transitions, and it has been the most beautiful thing that has happened to me. In some ways, I experienced it somewhat alone at first, and now it's completely shared. My ultimate dream is that no one else will experience a transition alone.

-In these times of fascism and hate speech against trans people, what use is poetry to us?

Poetry says everything without bombarding us; it can be something as subtle as describing a drop of water falling peacefully from a tree. It's a space to retreat to spiritually when there's chaos outside. In this capitalist world that teaches us to be productive even as we're being killed, poetry allows us to gift ourselves feelings and reflections to comfort ourselves, to keep us company, or to release our anger. It's giving ourselves a space of spirituality and encouragement that we can create in silence, both alone and collectively.

-What message would you give to a trans person who is afraid to show what they write? How would you invite them into the world of poetry or simply writing?

To begin with, I would tell you: I'm sure you're all writing and keeping it hidden away. But I also understand that there's a lot of fear, yes, obviously, of exposure. The fear of being read and, therefore, seen. We're afraid of what people will read from us, because we're giving the world our hearts. So, from what's hidden away, choose what you want to show and do it, because it's necessary that you be read… it's time to take the floor and not let anyone else take it from us. Let's not let anyone else speak for us.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.