Ballroom: Lesbianism, transmasculinities and non-binary people on the dance floor

Ballroom culture is strengthening as a space of resistance and chosen family. In Mexico, the ballroom scene is breaking away from "the gringo" and transforming into a community for lesbians, transmasculine people, and non-binary individuals.

Share

MEXICO CITY. Ballroom culture has established itself as a space of resistance and affirmation for dissident voices, actively seeking to "shed its American influence" and contextualize what is experienced within Mexican territory. Annia Ninja, Kintsugi, Sijé, and Estrella are some of the people who are building the ballroom community in Mexico City. This scene is a microcosm that offers moments of celebration but, as they tell us, is also permeated by internal violence that reflects the problems of the world.

This comic explores how lesbians, transmasculine and non-binary people ball

Swipe to see the comic

Lenchitities, self-management and balls

In Mexico City, the first ballroom event took place in August 2015. Sapphic representation was scarce in the beginning. Women were forced to "carve out a space for themselves in ballroom ," says Annia Ninja, a dancer and ballroom in Mexico. "At that time, there was still resistance to a certain misogyny from gay men," she recalls.

Visibility as a lesbian community was consolidated with the emergence of self-managed spaces. Lenchas Kikiball, the ballroom scene in Mexico, celebrated its fifth anniversary.

For Estrella, a photographer and observer since 2016, this kickball is “a necessary lifeline, one of the most beautiful and best organized.” From her perspective, it is the “least violent” kickball

There is a lot of work to be done. “There is still a lot of work to be done so that lesbians feel included in all scenes or balls in Mexico,” says Annia.

Transmasculinities and non-binary people in the Latin American scene

The Latin American scene stands out for being more open to non-binary identities than the US scene, explains Annia Ninja. This is partly because class issues in the region have driven the community to "embrace other transitions" that don't depend on "transmedicalist" discourse (surgical or hormonal procedures) to validate identity.

For non-binary transmasculine people like Sijé, ballroom dancing was "a fundamental part of my transition," helping them to define themselves from an identity that had been relegated. Sijé, from Kiki House of Travela, recalls that, "transmasculine people would go into ballroom dancing and leave because we weren't given space. There's still a lot of invisibility."

The +Kulones kiki ball , dedicated to transmasculinities, was a turning point. After the first event, Ángel Sijé felt that “everything made sense.”

“Seeing that there were so many of us, and so different, that ball became a turning point for me, a moment of euphoria and support. It helped me realize how diverse transmasculine people are. It also introduced me to other role models and made me realize that I could be one too,” he recalls.

Despite this, barriers persist. Transphobia and misogyny toward transmasculine bodies are rampant, says Ángel Sijé. Furthermore, non-binary people continue to face questioning. Sijé personally experienced comments about his body and genitals.

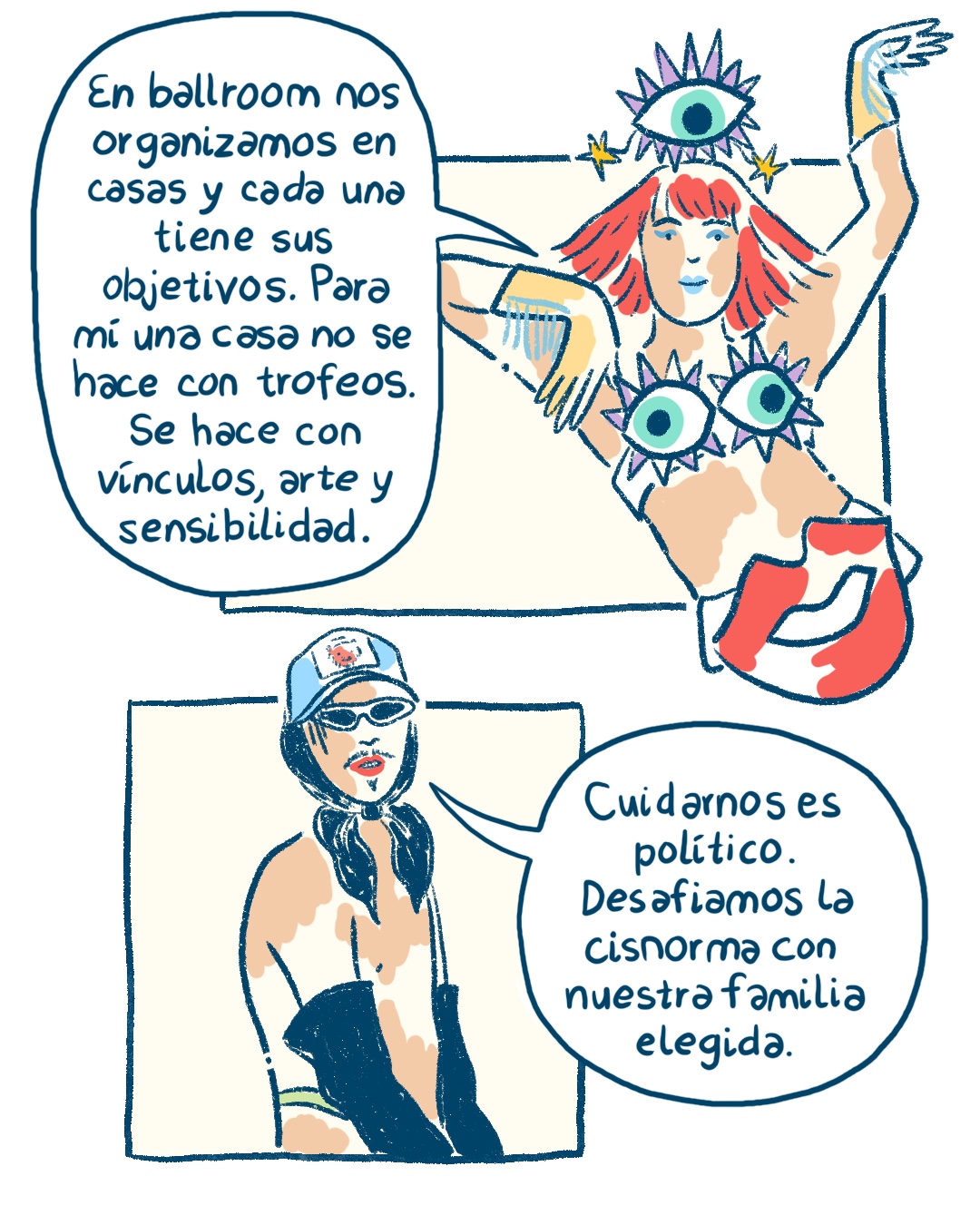

Politics, family, and recovered time

Ballroom dancing is inherently political. The act of voguing , swaying wrists and hips, having fun, protesting, and creating a fantasy world is a political act in itself.

Kintsugi, the father of Kiki House of Millan, observes that the tropicalization of ballroom includes “direct protest.” The ways of expressing this are not based solely on the ball's themes, but are linked to structures that are disrupted in ballroom culture, such as the concept of family.

“In a context where fascism defends the traditional family, the emotional bonds in ballroom dancing represent the conviction to accompany each other, to embrace each other, to support each other. That is tremendously political and hopeful in times like these,” says Kintsugi.

Kintsugi, Annia and Ángel Sijé also find another gift in the ballroom : "the return of lost time".

“ Ballro om is the space where I can live a life that truly belongs to me. Every time I walk vogue femme , I exorcise the movements that were forbidden to me in my youth and adulthood. Here I can do and be whatever I want,” Kintsugi explains.

Community challenges and the future

Although ballroom creates spaces of care and support, violence, neglected complaints, and silences that allow it to continue are also present. Estrella, a witness to this decade of ballroom in Mexico City, says, “The reports of violence and harassment really disappointed me; they broke my heart.”

Annia laments that ballroom dancing “isn’t reaching children and teenagers. The kiki , which was born to educate, prevent addiction in young people, and support those affected by violence, isn’t focusing on LGBT+ children and teenagers. On the contrary, the scene is aging—and not because aging is a bad thing—and is mostly populated by people in their 30s and 40s. I do believe it’s a conversation we need to have to involve children and older adults as well,” she explains.

In ballroom dancing, each category you walk is like opening a vault of memories. It not only showcases brilliance and creativity but also the pain and violence experienced by marginalized communities, such as denied identity, the lost time in their youth that forced them to suppress their hip movements, their wrists, and their dreams of being whatever they imagined.

Kintsugi adds that, as a community, ableism must be combated. “I wonder how much we are adapting the space where balls for someone who wants to walk and lives with a physical disability or some neurodiversity.” Kintsugi concludes that, furthermore, “ ballroom must be inclusive. Our liberation as LGBT people will not happen until there are no more genocidal far-right groups in the world.”

Juntes Narramos is a project by Malvestida , Volcánicas , GirlUp , Balance and Presentes to strengthen and amplify the voices of young people through narratives of diversity.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.