Poni Alta, the trans zine maker that promotes counter-narratives and community from Mexico City

“Making a fanzine is a very beautiful and direct way to take control of your narrative,” says Poni Alta, cultural manager and founder of aluZine, a space for exchange and dissemination for and by trans people.

Share

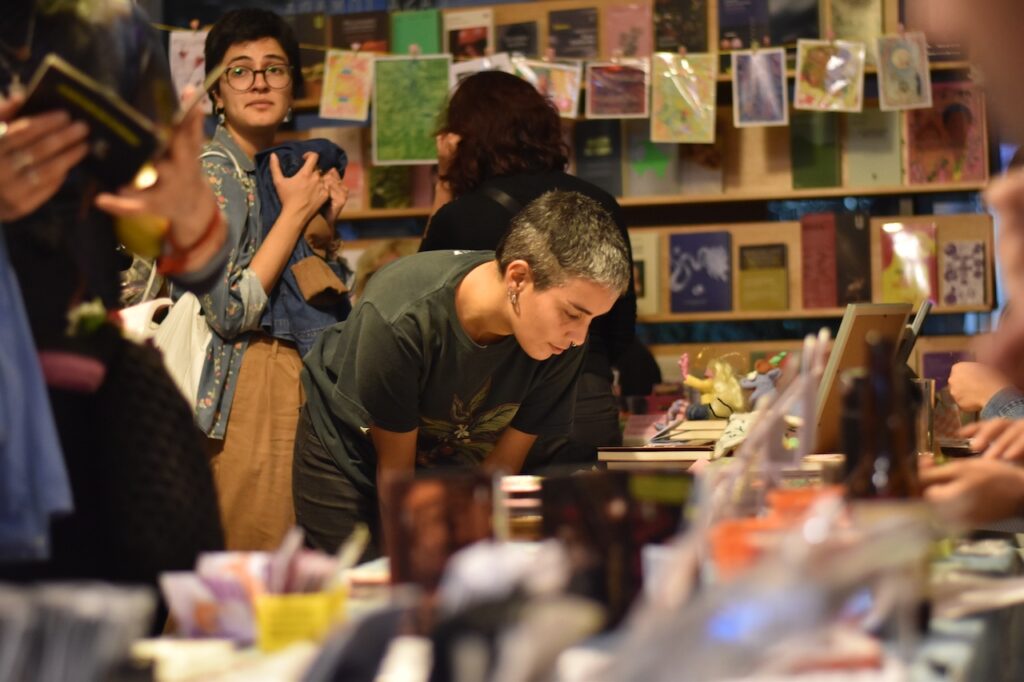

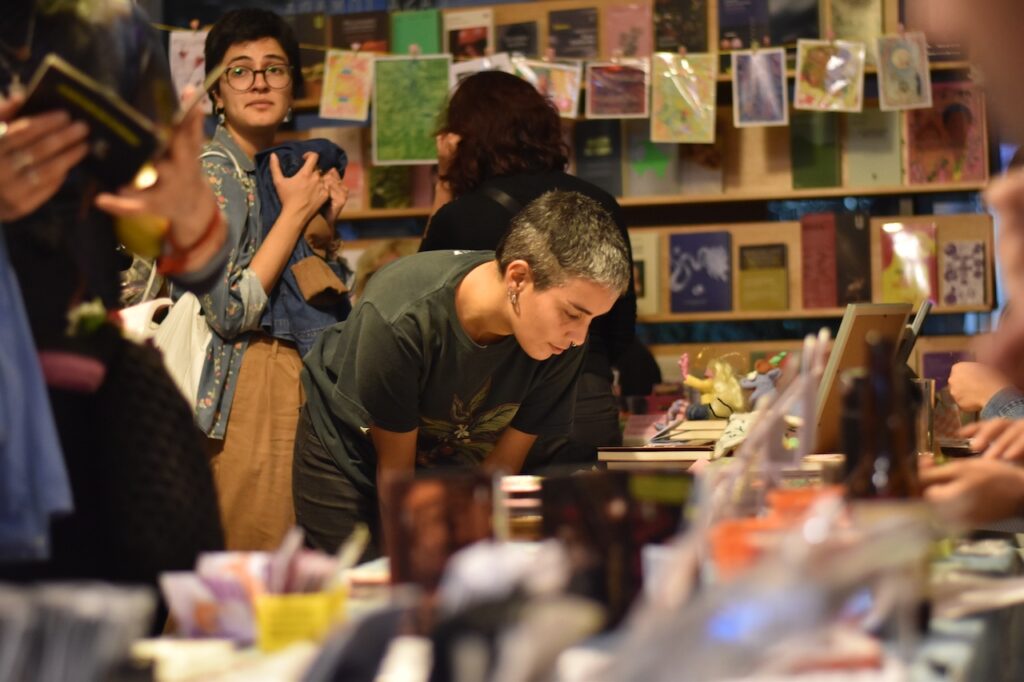

MEXICO CITY. Poni Alta found the Mexico City zine scene sexist and misogynistic. This prompted her to consider the need to create safe and representative spaces for dissident people. This urgency culminated in the creation of the trans zine fair, aluZine , which celebrated its second edition this year. This festival focuses on promoting the work of trans people from Mexico and other Spanish-speaking regions.

In 2025, the festival focused on the genocide against the Palestinian people. Transsexuals for Gaza , or T4Gaza, brought together sixteen authors, including a mini-fanzine. The proceeds are sent to families, organizations, and activists in Palestine through a local fund organized by friends.

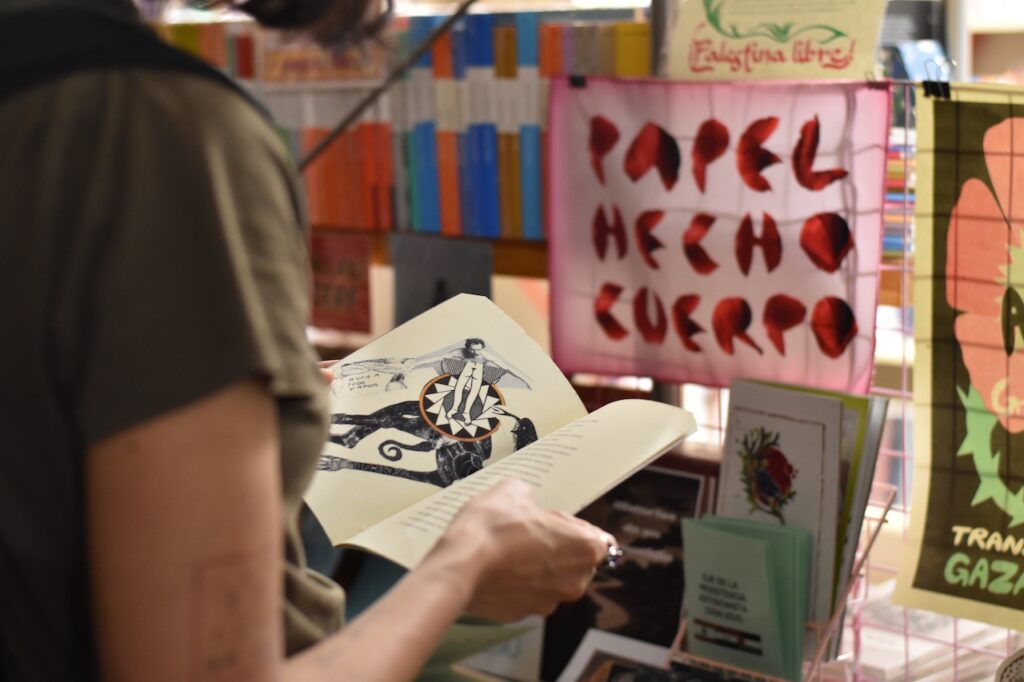

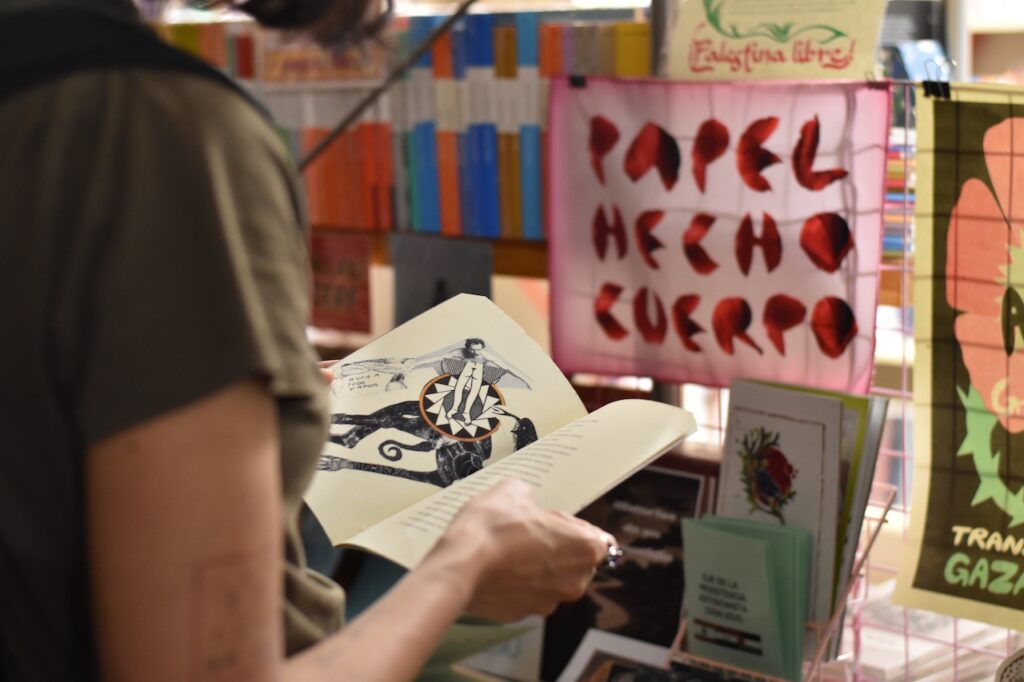

Poni emphasizes that the fanzine , thanks to its accessible , is a crucial medium for constructing counter-hegemonic narratives and a "pack" of support and connection . The power of the fanzine, she says, lies in the fact that, as a self-managed object, it allows people to "take total control of your narrative and leave a mark of who you are."

Poni is a trans zine maker who is redefining the self-publishing landscape by using the zine as a counter-narrative approach.

To put things in context, what is a fanzine, and how would you define it?

For me, a fanzine is like an extension of the person who makes it. There's a lot of physical involvement in the process. From an idea that comes to you one afternoon when you sit down after work to draw or write it, the fanzine is you editing it, you going to get it printed, folding it, stapling it, going to the fair, bartering. I mean, that whole part of the process is you. And the result is a little body made of paper, which is distributed and becomes part of someone's home, allowing the person to share their being with the world.

Making a fanzine is a beautiful and direct way to take control of your narrative and leave a small mark of who you are in this world. It's a form of permanence, far removed from the algorithm and the digital realm. The fanzine offers that tangible form; it has a body that you create with your own hands.

Who is Poni in the fanzine world and how did your interest in this self-publishing format begin?

I started making zines around 2017. I was finishing my architecture degree, and a friend had shown me some comics he'd made using AutoCAD (the drafting program). I thought it was crazy. The realization hit me during a year-long exchange program in Berlin. While I was there, I went into a queer zine shop and thought, "I could be doing this, I already am." My first project, which was like my zine baby, was about painting my nails pink, having conversations with people, recording them, and then turning that into a zine. They were profiles of the people I talked to. That's how it all began.

My zine name is floresrosa . I liked the idea of thinking of flowers as something soft, feminine, and with a rich aroma, but at the same time intense in color, in their senses, and sometimes even in their texture. Returning to Mexico, I applied to several fairs. Although I'm shy, I had a moment of inspiration, and I realized that I really enjoy management, putting everything in place to make things happen. That's how the idea of organizing zine fairs for trans people was born.

How was that awakening of your trans identity and the beginning of the aluZine trans fanzine festival?

As I got to know the zine community, I also got to know myself better. I began to understand myself as a trans person. I found a lot of creative freedom, in terms of formats and media, within the scene, but I also began to encounter its staleness. I realized that the city's zine tradition was closely tied to the punk movements, which brought with them sexist, misogynistic, and homophobic attitudes. It bothered me that I wasn't given certain opportunities or that people didn't connect with what I was doing.

I no longer wanted any kind of hegemonic representation. So, with some other people, I started another festival, but I ended it when I felt TERF infiltration. From that need, Borrón y Cuenta Nueva (Clean Slate) , a trans fanzine and graphic arts fair, emerged. Later, together with Oso from the Transmasculine Archive , the idea for aluZine arose. Today, I believe that's my place: yes, I'm a fanzine maker, but I enjoy managing spaces where trans people can come together to make, read, and exchange fanzines.

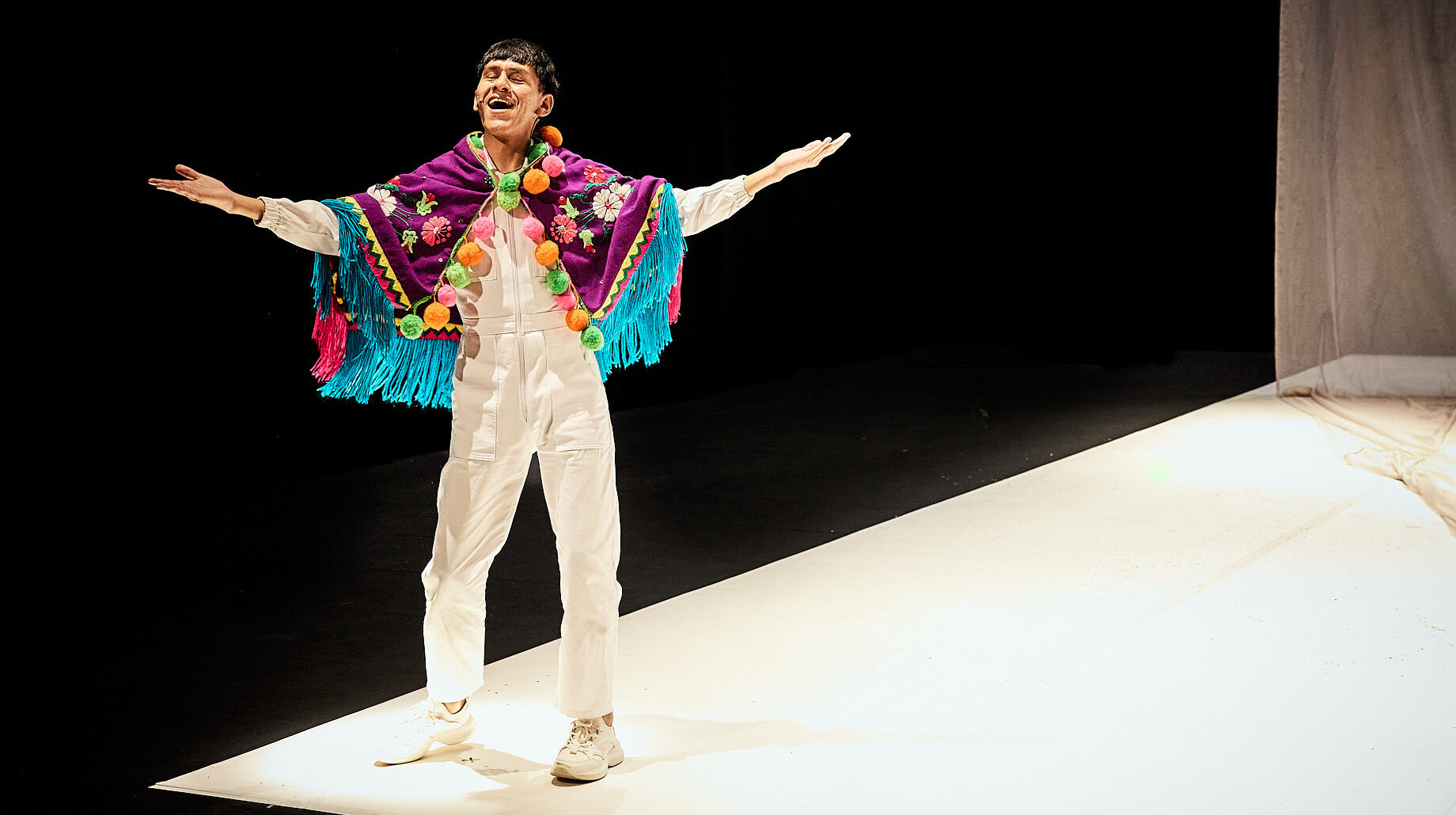

Photo: Habitita el vacío

Why is it important to create these specific spaces for and by trans people, in addition to focusing on the fanzine?

It has to do with the construction of counter-hegemonic imaginaries. The fanzine has always been a response to that which doesn't fit into the mainstream media. Although there have always been dissidents and women in countercultural scenes, historically they have only been tolerated, without being given the space to truly transcend . The fanzine is a very accessible medium; it doesn't require great wealth or academic background, and it's a very rich form of expression. In the end, being there has the value of knowing that we are enriching and mobilizing discourses with our mere presence. People who self-publish are trying to find their place in the world.

AluZine is also a festival that brings together zines by trans people from around the world. In the two editions of this zine fair, what have you found? What are trans people talking about in the zines they create?

We talk about various things. The themes fall into two categories: on the one hand, experiences and sensibilities, and on the other, let's burn it all down. For example, in the calls for submissions, we've compiled titles from all over Latin America. There was a poetry collection by trans gay men from Argentina who talked about being trans gay men, and there were also several fanzines of transfeminine and transmasculine poetry, and nb—I think poetry comes naturally to trans people.

A fanzine that really made an impression on me was a book of poems by a Peruvian artist named Gretel Warmicha. Her writing is beautiful, confrontational, and highly symbolic. I remember she was very excited about the printing of things here, and it created a lovely feeling of connection across the distance. From the first edition of aluZine, we printed one by a very dark, lesbian trans woman, which was a game of witchcraft under the full moon. And from the most recent edition, focused on trans people in Gaza , I found a fanzine that was a beautiful collection of images of flower landscapes in what is now Palestine and Gaza, interspersed with pro-Palestinian graffiti. I find it very powerful because it's beautiful to look at, but it also has its unsettling aspects.

What has self-publishing given you, besides these encounters?

It's given me a space to find myself creatively and narratively. In the end, I like to say that the fanzine is like an extension of the person who makes it. It's the whole process: the idea, drawing it, editing it, printing it, folding it, stapling it, going to the fair, and swapping it. That little body made of paper gets distributed and becomes part of someone's home, which gives me the opportunity to share myself and feel welcomed by people. It's a reach that I find very healthy and beautiful, because it's not massive or viral, but very one-on-one.

What would you say to the band to encourage them to make a fanzine?

A fanzine will surprise you; it's like a little vomit that explodes in your face, but you love it and crave more of that raw, pure reality. Sit down and make one. You just need the desire to say something to the world—anything, it doesn't have to be important. Sit down, staple something together, and give it to someone, or sell it to someone, or alter it, and that's it… you don't need much more. It's a way of constructing subjectivities and thinking about ourselves outside of hegemonic systems.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.