Tiziano Cruz: Quechua, Aymara, and queer pride

“I don’t do documentary theater, I do political theater,” says Tiziano Cruz, the Quechua, Aymara, and queer artist who challenges from stages around the world.

Share

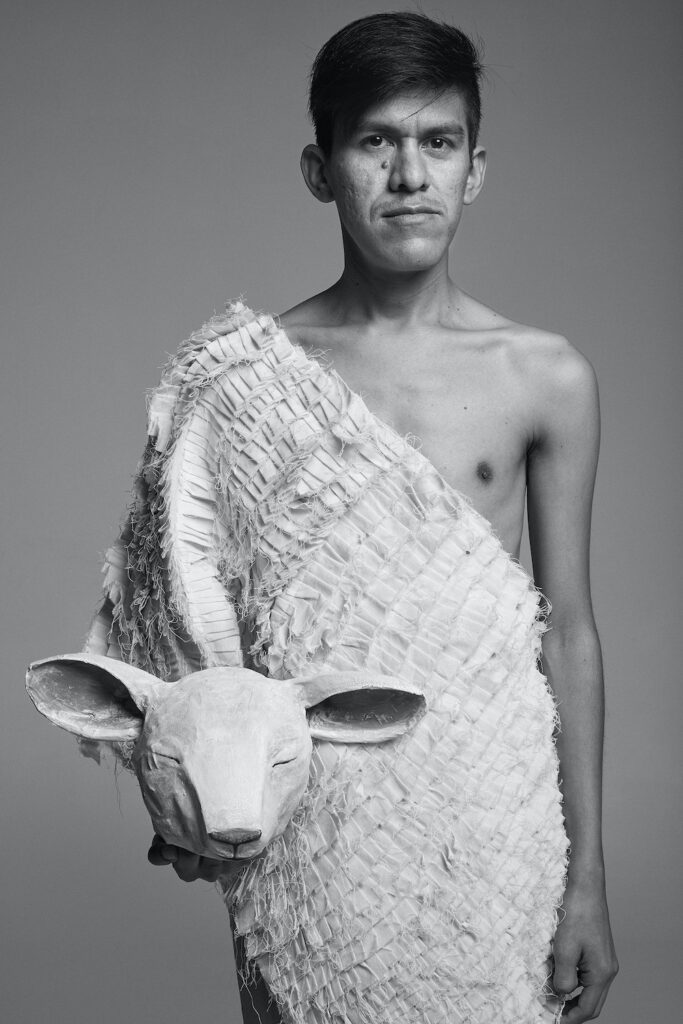

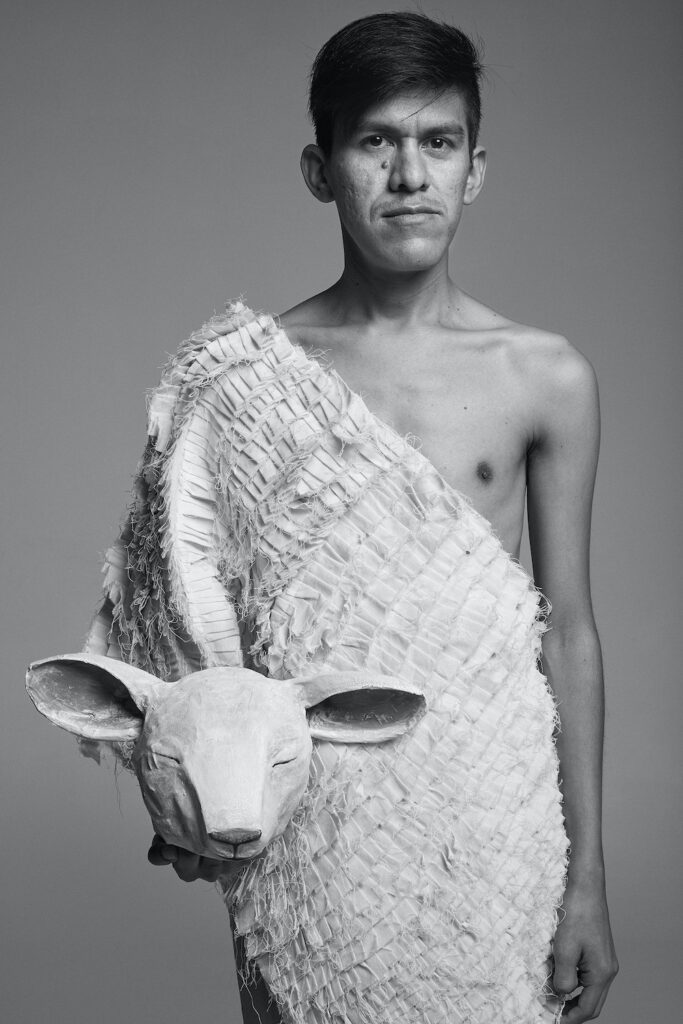

Photos: Christophe Raynoud de Lage (opening, Avignon Festival), Matías Gutiérrez, and Nora Lezano

When Tiziano Cruz takes the stage, he does so with denunciation, tenderness, and a provocation that dwells within both grief and reconciliation. “I am from the Quechua and Aymara community,” says this artist, born on October 15, 1988, in San Francisco, Valle Grande, Jujuy. Since 2022, he has been touring the world presenting his works: “I don’t do documentary theater, I do political theater .”

With her trilogy “Three Ways to Sing to a Mountain,” she embarked on a path to global recognition. Her childhood memories highlight the racism and classism present in society and the art market. In one of the pieces, Soliloquy, she explores this through 58 letters written to her mother during the Covid-19 lockdown. Wayqeycuna, the second piece, is “a desperate attempt to end the grief of losing my sister.” A sister who died due to the negligence of the healthcare system.

Each work in his trilogy focuses on a different family story: father, mother, and siblings. He concludes with an epilogue dedicated to water.

When she started high school and her parents separated, she, her four siblings, and her mother moved to San Salvador de Jujuy. There were six of them in a very small room. “I always say that at that moment I fell in love with the middle class,” she explains to Presentes, recalling the lives of her classmates with present mothers and fathers, and basic, everyday services that were foreign to her. “If that exists, why can’t I have it?” she thought.

He focused on education as a tool to access the life he observed. But even that didn't work out. His thinking, because he is part of an Indigenous community, he says, is under scrutiny. The daily aggressions he faces at various levels remind him that there is a system that excludes him.

For almost seven years, he worked at the Recoleta Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, where he was Head of Artistic Content Production. Sometimes, if someone asked a question, they would address the person next to them, not him. “There are a lot of things you know you have to work twice as hard for because of your skin color,” he concludes.

He was a recipient of grants from the National Arts Fund and the National Theater Institute of Argentina, and winner of the 2019 Young Art Biennial. His art has spread to Chile, Brazil, Mexico, the United States, Canada, Portugal, Spain, and Germany, winning the ANTI Prize in Finland (2023) and the ZKB Audience Prize in Switzerland (2024). In Argentina, he says, things are different. His works, he explains, don't resonate; few see them: “I'm aware of my body type and my background. That's why I'm not validated by my peers in the performing arts and academia.”

A few years ago, in Switzerland, he went to a concert by the Russian feminist punk rock collective Pussy Riot. The music, the screams, everything sounded extreme, freedom and rebellion on stage, but among the bleachers, curled up in his own calm, was Tiziano. “I fell asleep.” Listening to him, it’s almost unthinkable that anyone could sleep in such a scene. “I felt I could sleep knowing I wouldn’t be stabbed for who I am, for where I come from. I felt a security I don’t feel here.”

Community power

In his works, Tiziano Cruz calls upon local communities to share their voices and be paid for their artistic work. “They have been stigmatized all along, denied access to these spaces. These are people who are performing in theaters for the first time, who in their entire lives have never even had the chance to see a show.” And he prepares for another provocative statement: “Theater remains a bourgeois practice. Tickets can be free, but some people still won't go; there's an intangible barrier that says this cultural practice isn't for them.”

In his text "Life as Commodity on the Gondolas of the Contemporary Art Market," he objects: "We have been colonized by the narratives of a Eurocentric-Aristotelian theater, which has become embedded in our geography." Tiziano speaks of a local theater that, in his view, only seems to address themes like "the dysfunctional family." He doesn't present it as something innocent, but rather as a modern ally of colonization. That's why he uses his body to speak about poverty, discrimination, and the erasure of his communities.

“It really bothers me when people say that the personal is political.” What each person says as something personal will only be interesting if it brings a biography that articulates reflections on themes relevant to a large part of the population. He acknowledges that biographical elements in theater are often associated with the bourgeoisie, but when approached from a marginalized perspective, they can be revolutionary.

“ For indigenous cultures, the future is behind them and the past is ahead .”

“I sell out to the market, and in my work I apologize for that,” he says, not to justify himself but to provide context: “It’s said that to make anti-establishment art you have to be independent, not compromise with the markets. I don’t think that’s the case; rather, being anti-establishment has to do with the possibility of what you’re trying to say and what practice you’re trying to share.” It is this market that finances him and allows him to live, and it is from this perspective, and with the artistic value of growth, alliances, and tools, that Tiziano returns to the community.

That's why she created Ulmus, a platform that supports artists from Northwest Argentina (NOA) in achieving visibility, sustainability, and international recognition. From there, she and her team empower local talent through training, production, promotion, residencies, and tours. "A percentage of what I earn abroad goes toward supporting their work." Now the project has joined forces with LODO of Buenos Aires, becoming UlmusLodo . She explains that thanks to this collaboration, local artists are currently performing in Costa Rica and Chile. Victoria Pastrana , from Amaicha del Valle, won the European Prince Claus Seed Award (Netherlands), an international recognition for emerging artists. At the same time, in her community, she is involved in the creation of the first Indigenous cinema and several books, all "to help revitalize the language."

For Tiziano, Indigenous philosophy, rooted in community, is fundamental. He quotes the Brazilian Indigenous philosopher Ailton Krenak: “The future is ancestral.” He adds: “ For Indigenous cultures, the future is behind us, we don't see it, and the past is ahead , it's what we can see and work with, the opposite of the Western idea.” By looking at what has already happened, at what we have lived through, we can act, but not in isolation.

Sometimes, when he speaks at a conference, people ask him what water to drink or how to live better in this globalized world. “Everyone wants something like the secret to a good life, but not for you to have a political or ideological stance.”

“I wouldn’t have been able to survive if I were a heterosexual person.”

Photo: Nora Lezano

Tiziano participated in a Pride March for the first time in 2024. It was in Tilcara, Jujuy, and “the flag leading the march was the Wiphala: “Our identity as people who defend a territory, an ancestral heritage, comes first.” Everything else is secondary, “and not in a bad way; I may have other urgent matters, and that doesn’t invalidate the others.”

Recently, while watching the film based on Camila Sosa Villada's book, *Thesis on Domestication*, she allowed herself to connect with questions that had been sidelined by the urgency of survival. "They've made us believe that no one can love us, that everything will have to be clandestine, that we're going to die alone," she says. In the present, the sting of this disbelief, this feeling of not deserving of support, still throbs. "I'm tired," she says, knowing that her life is a thousand lives for other identities, that everything she's had to endure has never given her a break. "Now that some of my needs are a little more met, I'm finding that other thing." That other thing: the love and care we deserve.

When he talks about being in a relationship, he does so with the same tenderness and commitment he displays when being incisive; he embodies both the sweetness and firmness of someone who has been through a lot. Tiziano identifies as queer; that term feels more down-to-earth, more streetwise, a search for another way to define himself. And he keeps telling himself that if we're queer, if we aspire to be hegemonic gays, what's really needed is "to work harder on finding our own way of defining ourselves."

In this way of facing the world, that other sensibility found the tools to survive. “Heterosexuality is much more traditional; that doesn’t mean there aren’t members of the community who are extremely conservative, but in my case it has taught me that you create your own family.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.