Trans Mocha Celis High School: educating in community as a response to hate

The Mocha Celis Transgender Popular High School is about to celebrate its 14th anniversary. While deepening its academic work, it is preparing for a new edition of Mocha Fest, which will take place in November.

Share

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina. The demand for free, quality public education united the Argentine people in a common cry. It was one of the demands directed at the government of Javier Milei that garnered massive support and inspired huge street protests. The three Federal University Marches put education on the agenda and succeeded in overturning the presidential veto of the University Funding Law .

With that veto, not only was the country's education jeopardized, but also spaces for care, social integration, and the future trajectories of students: the social role of educational spaces. In a context of crisis, with a fractured social fabric, rampant hate speech, and the elimination of institutions that sought to address violence and discrimination, what is it like to study today for the most vulnerable sectors? In particular, what is it like for the trans, gender-diverse, and non-binary (TTNB) community?

“Demotivation in the face of an adverse social and economic outlook discourages educational attainment and the possibility of imagining a university career or formal employment,” says the Mocha Celis Transgender Non-Binary Popular High School .

A space that multiplies

La Mocha was the first high school in the world specifically for the trans and gender-diverse population . It set an unprecedented precedent , as we explained in this comic. Currently, its members are preparing to celebrate their 15th anniversary in 2026, as well as MochaFest on November 15th. At this twice-yearly celebration, students and alumni showcase their entrepreneurial ventures—gastronomy, textiles, crafts, literature, and art—and share a cultural space open to the community.

At the end of last September, they, along with other organizations, promoted the 4th Trans, Travesti, and Non-Binary Education Meeting in the city of La Plata, Buenos Aires province. Education workers and students gathered for two days to discuss the educational landscape and access to education in the region. Participants included officials such as the provincial Minister of Women and Diversity, Estela Díaz; and authorities from the National University of La Plata and the National University of Avellaneda; among others.

Among their activities, they developed a Collaborative Mapping of TTNB Educational Spaces , which is currently in preparation. “It already includes more than fifteen educational spaces, with the goal of helping prospective students find a place that will welcome and support them,” they shared.

Undeniable progress

From Presentes, we spoke with Virginia Silveira, president of the Mocha Celis Civil Association; Francisco Quiñones, director of the high school; and Juana Ramella, academic secretary. We discussed the current challenges facing these educational spaces, the efforts to ensure student retention, and the social role of education.

-How do you see access to education for transvestite, trans and non-binary people in this context in Argentina?

-The latest research conducted by Mocha Celis in conjunction with the Public Defender's Office—published as “ With a Name of Their Own: Ten Years After the Gender Identity Law ”—recorded a slight improvement in access to education for transgender and non-binary people after the law's enactment. However, we are currently witnessing a setback: maintaining schooling is becoming increasingly difficult.

On the one hand, material conditions are one of the main barriers. Resource transfer programs that supported educational pathways have been cut, and more and more students are finding themselves homeless. On the other hand, a historical reason for exclusion has resurfaced: discrimination. The elimination of the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity, along with the dismantling of INADI ( National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism), represented enormous institutional losses. The stalling of the implementation of the Transgender Employment Quota Law had a direct impact on access to education: it restricts the possibility of accessing formal employment that would allow students to complete their studies. This forces many people to resort to precarious survival strategies that are incompatible with continuing their education.

-What is it like for those who do manage to stay in school?

Those who remain within the traditional education system face other obstacles. These include the lack of effective implementation of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) with a gender and rights perspective, and the prohibition of non-binary language in schools in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires since 2022. This undermines compliance with the Gender Identity Law. Furthermore, the rise of hate speech in public spaces has concrete consequences because it enables violence and creates a climate of insecurity. Both of these factors directly affect the retention of transgender and non-binary students in educational settings.

Educating in violent times

–What challenges do TTNB education spaces face today?

Many TTNB educational spaces face common challenges. Among the main ones is the lack of stable funding, which prevents us from sustaining daily activities and planning for the medium and long term. Another recurring problem is the state of the buildings: most spaces lack their own building or operate in precarious conditions. Added to this is the lack of teacher salaries and basic material resources.

Faced with the increasing precarity of life, these spaces must encompass a broader range of support. This includes not only education, but also housing, food, and healthcare. In many cases, the responses depend on the dedicated commitment of comrades who, even without state support, sustain the continuity of these projects with enormous effort. Furthermore, we observe a general lack of institutional support from the State and a lack of specific public policies to strengthen these educational and community-based initiatives.

–What difficulties has this population historically faced in accessing education?

-People in the LGBTQ+ community often face early expulsion from both their homes and educational institutions when they express their gender identity. This interrupts their educational paths. Adding to this is the situation of many migrant peers who arrive in the country without educational documentation. This situation forces them to restart their studies from the primary level. Through the Access to Rights Program, we support these processes and, in conjunction with PAEByT (Literacy, Basic Education, and Work Program), we inaugurated the Flavia Flores Primary School, aimed at ensuring educational attainment.

Housing problems are a determining factor. Maintaining their education is nearly impossible for those who are homeless or living in hotels. Job insecurity also directly affects their ability to stay in school: many students have had to increase their working hours after being laid off from formal jobs they had obtained through the Transgender Employment Quota.

Support in academic pathways

–How do they work to ensure school retention?

Our support is comprehensive and aims to ensure students remain in school. We have several programs: Teje Solidario, a care network that provides a monthly food basket and a community clothing rack; Empleo Trans, which assists with CV preparation, job searching, and job retention; Acceso a Derechos, which addresses housing, health, identity, and migration or transition support, as well as support for incarcerated individuals and resource transfers; and the School Cafeteria, created by alumni to guarantee at least one meal a day. This year, we added an important step forward: the implementation of the student bus pass for adults in the City of Buenos Aires. This alleviates transportation costs and is essential since our school receives students who travel long distances to attend.

–What are the career paths of graduates?

-They are numerous and diverse. Throughout the program, we support each student in developing their personal project, according to their desires and interests. One of our main focuses is educational continuity: many graduates go on to higher education institutions or universities, with which we have agreements that include scholarships and specific support. At the same time, through the Mocha Celis Civil Association, we run a vocational training program that offers courses in gastronomy, languages, technology, makeup, and trades related to the job market, promoting job placement and economic independence.

The relationship with the institution doesn't end with graduation: many continue to participate actively, either as teachers or in other strategic roles. The most emblematic example is Virginia Silveira, a graduate of the first class, who later became a teacher and is now president of our Civil Association. But she's not the only one: we have other graduates working on different programs and projects, which represents a tremendous source of collective pride.

“Our task is to rebuild community”

–How does education impact the lives of the TTNB community? What is the importance of guaranteeing access to education in a context of social and economic crisis?

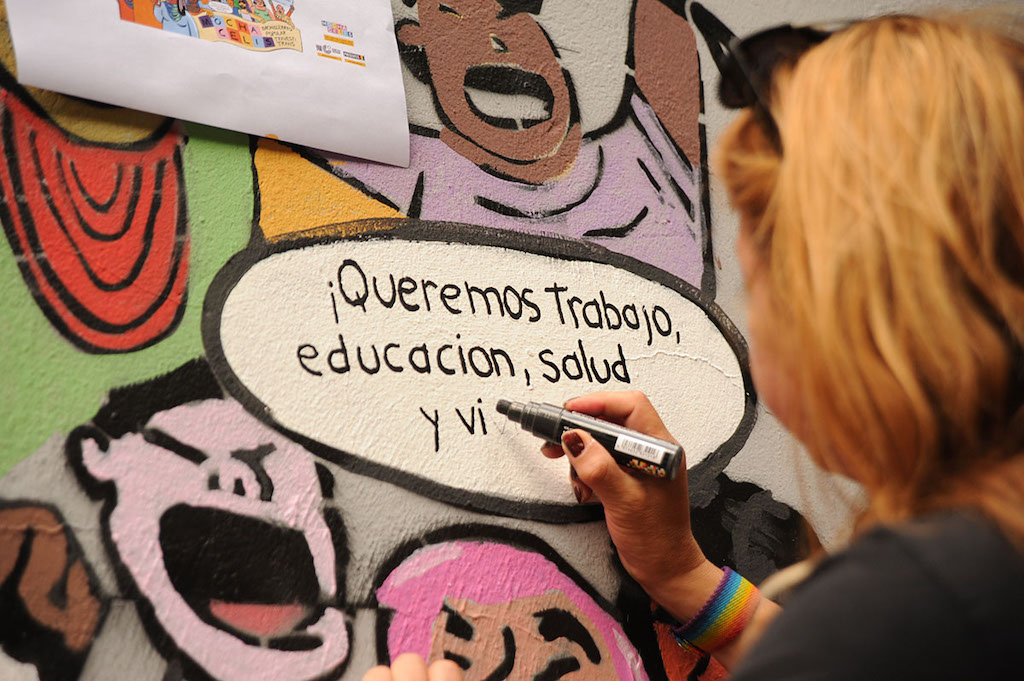

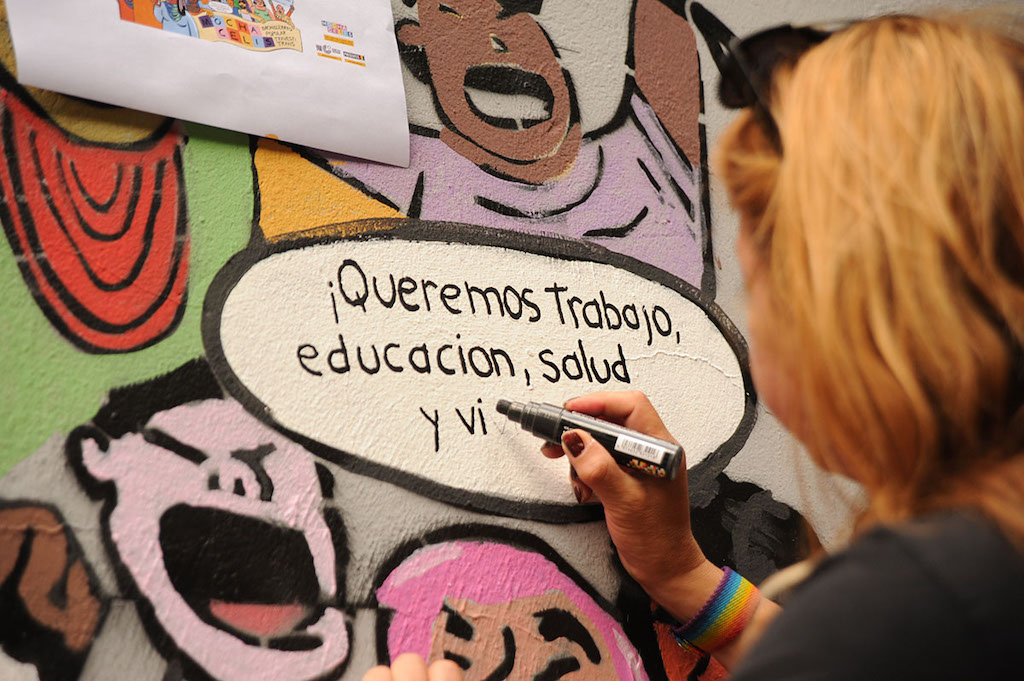

Education is a tool for individual and collective emancipation. It's not just about obtaining a degree, but about building networks, connections, and shared projects that strengthen the social and community fabric.

At Mocha Celis, we conceive of education as a space for holistic development. It allows us to learn about and exercise our rights, foster autonomy, produce knowledge and meaning, and train new generations of activists committed to defending human rights. Often, education is the gateway to other processes of restoring rights: access to housing, healthcare, employment, and identity. As Lohana Berkins , “To claim a right, you must first know it.”

–What is its importance in the face of hate narratives?

Hate speech has tangible, real-world consequences. It not only generates stigmatization but has also led to actions based on such rhetoric. Today, we face a political landscape where government statements and decisions legitimize these expressions and allow society to reproduce hate as a validated response.

Education plays a central role in dismantling these narratives. It is the space where we can question the common sense that constructs “public enemies”—not coincidentally migrants, LGBTQ+ people, and the poor—and replace it with a perspective based on human rights.

Faced with dehumanization, our task is to rebuild community and support life paths that are linked to people's desires, in order to overcome the obstacles imposed by discrimination.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.