Mariana Komiseroff: "Lesbians have historically been portrayed as violent."

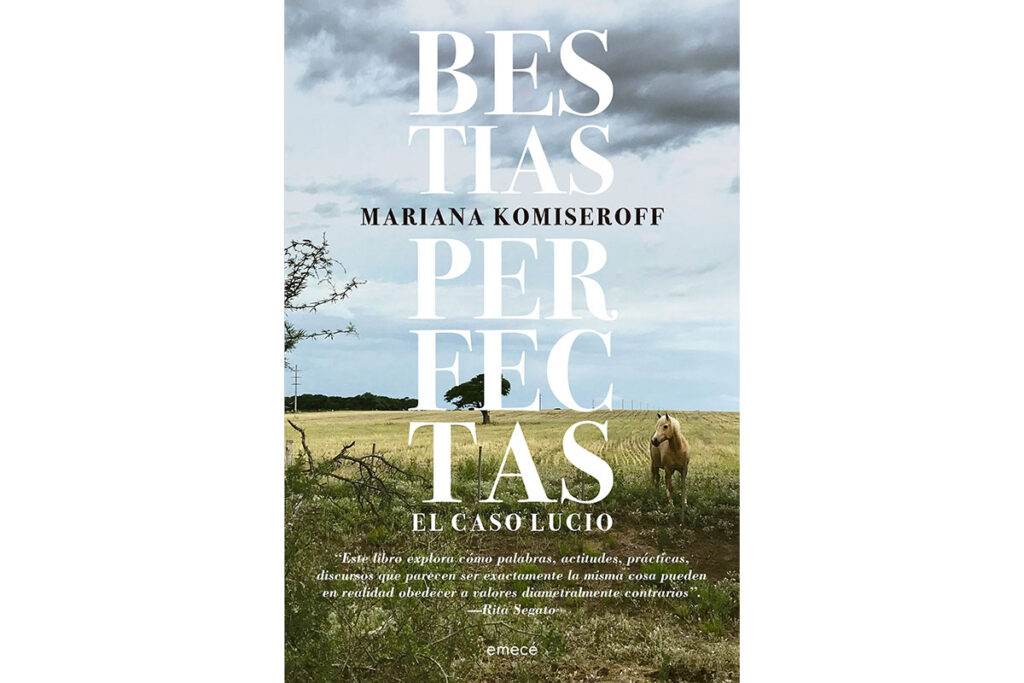

In Perfect Beasts: The Lucio Case, Mariana Komiseroff recounts, through non-fiction, one of the stories that shocked Argentina. In this interview, she analyzes violence against children, going beyond the stigma. “It’s a political moment in which hatred of children comes from the State.”.

Share

The scene of a group of mothers demonstrating with their children in front of the police station in Santa Rosa, La Pampa, where Mariana Komiseroff now lives, was the starting point for writing Perfect Beasts: The Lucio Case (Emecé). The text recounts an infanticide committed in 2021, which was at the center of controversy from the outset: the crime was committed by a lesbian couple.

In Perfect Beasts , Komiseroff explores all the complexities of the case through social analysis, from unwanted motherhood and feminism and antifeminism to societal mistreatment of their children. Furthermore, she raises a series of questions and issues that are, at the very least, unsettling.

How to look at it from feminist perspectives

That scene of the demonstration by mothers and children in front of the police station was the first instance Komiseroff witnessed of the cruel infanticide in La Pampa. At first, he thought it was a father who had killed the child of a lesbian couple. “It was the easiest thing to think,” he says. “The next day, the uprising erupted in Santa Rosa. But by then, I already had the information about who had killed the child. There were many questions, which of course I can't answer, and which I'll still be pondering. There were a lot of conflicts, but the first one I faced was that of ' the truth .' Then I relied on legal discourse. Because material truth is not the same as symbolic truth, the truth that each person holds about the events that happened to them.”

The book includes interviews with Abigail Páez's defense attorney, as well as with her mother, both of whom have already been convicted. This material was used to construct a map of facts, meanings, and questions, which are summarized in the prologue, where the most intense debate arises: examining the case from a feminist perspective. “I was somewhat afraid that the right wing might say, ' Even the lesbians themselves are saying they're murderers .' And I was worried that my own community might think, ' Why talk about this again ?' Because part of society thinks that feminists are to blame for this crime and that it's okay to shut down the Ministry of Women ,” she says.

– What happened once the book came out?

Unlike my fiction books, where there's always some comment or message, that hasn't happened with this book so far. I have received many messages from mothers, mostly short ones. One, talking about interventions on children's bodies, especially when it comes to their health. And another, a lot of messages from mothers telling me, for example, that they found themselves putting their child under a cold shower. Another saying, "I found myself forcing food on my disabled child." That's real life, and of course, it's the violence that Lucio Dupuy experienced, and it's also part of everyday life, something that often can't be talked about, discussed, or shared. Not even to tell other mothers, "This is happening to me, how do I deal with it?" To the woman who wrote to me about the cold water, I said, "Please, don't do it again." If you can talk to someone else about it, they'll have something to say.

"We are very alone in motherhood and caregiving."

-Including your experience with motherhood is important. Without that background, it's difficult to understand the chats between the two of them. What was it like for you to reflect on your own motherhood?

“ I’m interested in families, and especially dysfunctional ones . When I started writing the book, something about my own motherhood began to stir, even before my first contact with them. I started having nightmares, dreaming about the child, and remembering my own motherhood. For example, the story I tell about putting the baby in very hot water. I was a very young mother, I say this not to justify myself, but it wasn’t that the memory was veiled. I remembered, but I hadn’t been able to talk about it with anyone because it generated so much guilt. It was very difficult to write this book with the intention of portraying the murderers as beasts or monsters if I didn’t put myself in the first person. How can I talk about them without demonizing them if I don’t talk about myself as a demon?”

–And how do you think about it now?

Perhaps this book is an excuse to talk about forced motherhood, even when we decide to have our children and we love them and everything is fine . I think of it in the sense of Magdalena; she had already freed herself from her son in a way, because he was being raised by his paternal uncles. She decides to go and get the boy, and that's because she feels guilty. It's very common to hear people say, "Why the hell did she go and get him if she was just going to kill him?" It's a valid question. But why don't we ask why society expects so much from a mother, to the point that the mother feels more relieved with the child dead than with the child with the uncles? I myself tend to romanticize motherhood. But forced motherhood has many facets and depths that cannot be reduced to the abortion debate, yes or no . Even those of us who decide to be mothers and who want our children and love them. We are very alone in motherhood, which encompasses care work, because we are also the ones who care for others. Not only minors but also the elderly. And we are also very much alone in that task.

-How do you analyze today's meeting with them?

"I wanted to see them in person. Talking on the phone wasn't enough; I interviewed them by phone in October, November, and December. And I went to see them in January, two months later. And all that time I was worried they might change their minds. That was my relationship with the interviews; it wasn't moral. Of course, I have an opinion about what they did, which coincides with the Justice system's, but my interest lay elsewhere. The entry into the prison was more unsettling because I had never been inside a prison before meeting with them.".

I couldn't record, so I was focused on retaining the exact words as much as possible. After those visits, I recorded everything I remembered and everything that had happened inside. When I transcribed the material, I realized a few things. For example, I think it's because of my own bias against motherhood, and I'm more critical of Magdalena than Abigail. I can be more critical of Magdalena, firstly because I wasn't afraid they'd deny me the visit anymore—I was already there—and secondly because she represents the biological aspect. There's a biological aspect to it that, even though I believe biology isn't destiny, it affects me physically: this woman carried the baby in her womb. How could she allow it? Those kinds of details. But I was kind of detached; my emotions didn't play a significant role while I was doing the interviews.

"Lesbians are considered the perfect beasts ."

-Why did this crime shock society so much?

There's something of a self-fulfilling prophecy about it: two lesbians killing a child. But in truth, it's the only case of its kind in Argentine criminology . That, in principle, is an exception. On the other hand, I have all the material evidence of child abuse cases, and it's not that mothers don't intervene. Mothers intervene more than we'd like to hear in cases of torture and infanticide. They intervene a great deal, in addition, by covering up for their husbands. But generally, these are heterosexual couples. It's not common for it to be lesbian couples . In any case, we have to think about what we're reproducing within the LGBT community, that we still want to resemble heterosexual families even with these statistics.

-But there is a particular burden when it comes to lesbian women

Yes, and the same thing happens with trans women. Society's ideal is the male, so the worst thing is for a woman to desire another woman. But I mean, what about masculinities within the LGBTQ+ community, like Abigail, who also perpetrate this kind of violence? Does this mean that all trans men want to be straight, patriarchal, murderous men? No, of course not. But the privileges that men have are more desirable. Imagine not wanting the privileges of being a man, not even wanting to sleep with a man, not even wanting to have a family with a man… Societal thinking collapses with that. And besides, historically, lesbians have been portrayed as violent, masculine, and so on. The perfect beasts.

But there's more. Something very serious is happening, and that's violence against children . We're at a pivotal political moment in which hatred of children is coming from the State. The president fighting with a disabled child, a senator saying that the country's children don't have the right to be treated in a national hospital, the defunding of the Garrahan Hospital, the president's metaphors regarding child sexual abuse… Society is killing many children. But here, the prevailing idea is, "these two cakes killed the kid."

The pot boils over there, and that's how we stop looking at our own families . My suggestion is that we think from the perspective of our own families . They've already been judged; they've received the maximum sentence . It's striking that society continues to demand justice. And when I say this, I mean society in general, not the Dupuy family, the victim's family, who are also victims. Because I believe they have the right to confuse justice with revenge, but the rest of society shouldn't.

This interview was originally published in the Diario Tiempo Argentino and is reproduced as part of an agreement with allied media outlets.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.