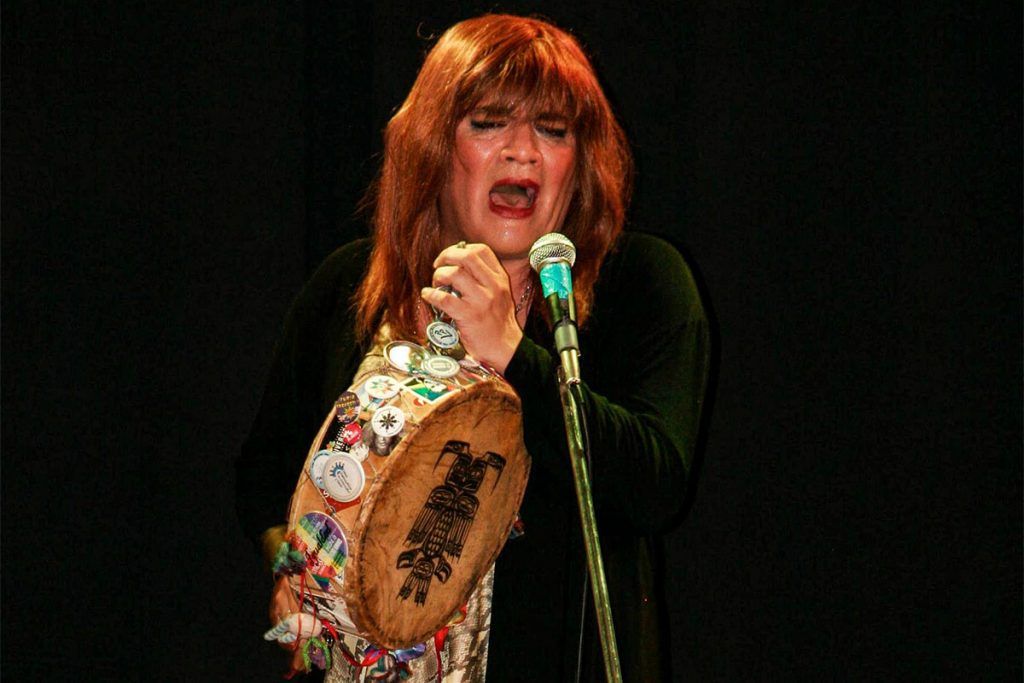

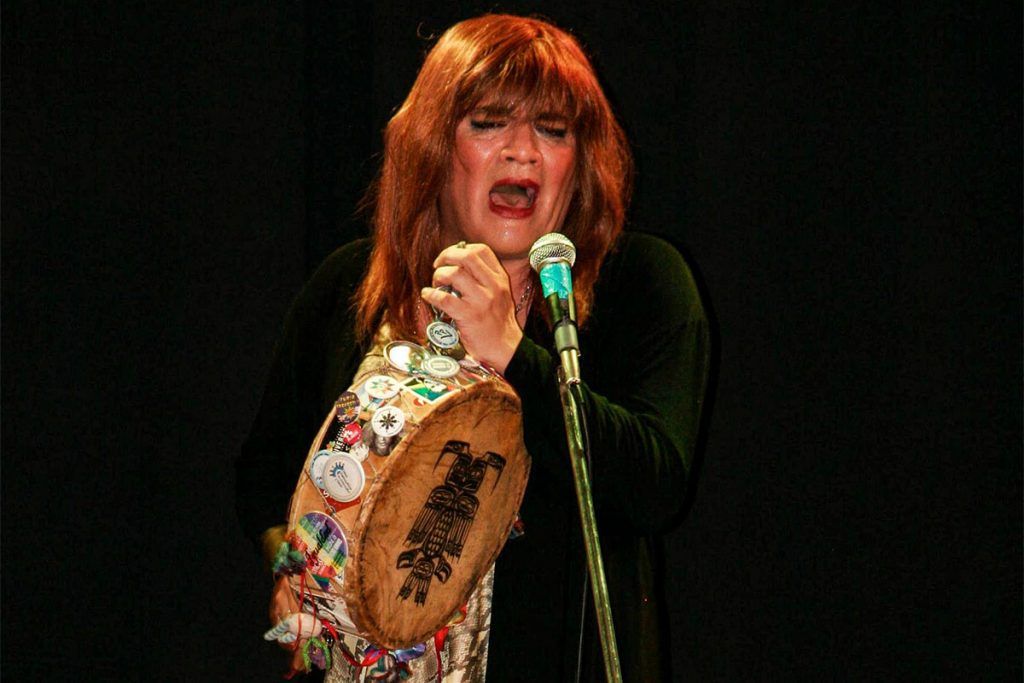

Susy Shock: “If you are not living your desires, you are living on borrowed time.”

Poet, singer, actress, writer, South American transvestite, and teacher. She tours much of Argentina independently, and her art is not consolation, but a loving rebellion for today and for what is to come.

Share

A key figure in trans activism in Argentina, Susy Shock has spent over two decades weaving a unique path from the south, where art, activism, teaching, and self-management coexist. Her latest book, La Loreta/Pibe roto , and the album Revuelo sur have taken her on tour through various provinces, in a political and poetic commitment to face-to-face encounters, to resistance through the body, music, and words.

Poet, singer, actress, writer, and educator of desire, she unfolds in each performance with her Flock of Hummingbirds an invitation to disobey the established order, to reclaim the collective, to seek meaning even in times when everything seems to be in freefall. “We must follow art, not only to be artists, but to be more creative people, which is what this era needs,” she says in this interview where she talks about her beginnings, her inspirations, the collapse of the system, the youth taking up the mantle, and new ways of creating community.

–You're a role model for many people and you always have words of encouragement and strength. Where do you get so much strength from?

"That's the question I get asked most often. As if I had a magic formula… I think it has to do with having projects, with seriously planning for the future. And asking yourself: are you living who you are, living your desires? I'm someone who's always been living my desires. That's what sustains you. All that stuff that New Age crap has stolen from us, and so it's lost its substance, like the word 'dreams' itself. I also think we have to keep looking at ourselves: where were we when the government changed? Where were we when our leadership failed us? Where are we now that the world is falling apart?"

These are the questions in this era of capitalist collapse. Milei and Trump are the people the system needs to pretend it's alive and well, but in reality, it's already crumbling. And are we in a position to confront anything other than capitalism? This isn't even a discussion for this government or the next; it has to do with profound human questions.

Everything that comes in this country is going to be tough, so we have to be prepared, knowing who we are and what we want. Otherwise, we're just passing through this life.

–Which people inspired you on this journey?

–First, my dad and my mom. A textile worker and a housewife who later became a doorman. They didn't read Foucault or Judith Butler, but they knew how to embrace the childhood they brought into the world. And that was key. Then, teachers who greatly influenced me: Miss Dolores, whom I honored in my book Crianzas ; Héctor Propato, a theater teacher; and, of course, Lohana Berkins and so many other women who supported me through art and activism.

–Your shows are a mix: texts, tango, folklore, performance. How do you conceive them?

–I don't even know anymore, but I do know that I see myself as a performing artist. I find it difficult to write something that doesn't first pass through my body, through the stage. There's a need to communicate knowing that someone is going to receive it. And that's political too. The important thing is not to lose sight of the collective.

–Last year you toured Europe. What was that experience like?

–Beautiful. We were in Berlin, Barcelona, Madrid, Bilbao, and also in Italy. And the most beautiful thing was the embrace of our own tribe there. Because they're far away, but they need a little bit of their country, their songs, to hear the local accent. We performed and also had talks with the groups that support Argentina is not for sale . It was powerful. And of course, we bring the latest album, but in reality, it's a whole body of work that we share.

–How did the Fufú Radio and what place does it occupy today?

–It stemmed from our experiences at Radio Nacional, where we did Brotecitos and La Cotorral with Marlene Wayar. When the government changed, we wanted that community to know we were still around. So the younger people around us suggested these streaming formats, which I feel are a code that works well for young people. I feel that something needs to be more carefully crafted, not just the improvisation of turning on the camera and starting to talk about anything. It's too important a time to say just anything. I think ideas need more time to develop and that we shouldn't get lost in the rush that the times encourage. Quite the opposite. So it's an experience where we're not in any race or ratings battle or any of that nonsense.

There are many more programs that are going to be launched, and it's also wonderful to think that we have plenty of time and that nothing is rushing us. The space is ours, for trans, travesti, and non-binary voices. When someone feels like it, they turn it on and start talking. And we can also wait, because there are ideas that need to develop.

–On your tours around the country, what kind of atmosphere do you find in this political context?

“We took a big gamble with my band. After releasing the album last year, we decided to go on tour. So we packed up the van and hit the road. And in the videos, I say, ‘We’ll come, you fill the venues.’ And that’s exactly what’s happening. There’s also this idea that if the government doesn’t support us, it seems like nothing’s happening. But I think we’re artists who have rarely been supported by the government to tour the country. We’re self-managed artists. I toured the country before thanks to a bunch of young people, before or during the same-sex marriage debate, who raised money in their provinces. We’d stay at their houses, put on shows, they’d fill up, and that’s how we made a living.”.

In a way, this tour is about injecting that energy and also valuing self-management. So far, what's happening is beautiful. At each performance, we also invite people to create altars.

–Altars?

–Yes. They're usually organized by local trans people. It's beautiful, because it includes not only the symbols of each place we visit, but also images of those who are no longer with us, and that gives it a beautiful spiritual weight. I feel there's something about ritual that needs to be reclaimed in such a frivolous, shallow time. We need to stop and acknowledge that we still matter. There are so many things that still matter to us, and so many people too. And so much of what makes us who we are still important. So, if this tour helps us position ourselves from that perspective, and to politically differentiate ourselves from this messed-up era, then so be it.

–Do you feel that there are new generations taking up the mantle?

“I feel that today there are many valuable people, a youth with a beautiful memory, who grew up with the names of Lohana and Diana Sacayán, even without having personally experienced them. That speaks to a collective memory we possess. I don't know if that will emerge from our own experience. Perhaps we need to build the possibility of other narratives from a community perspective. I lived in a country that had that fabulous trio—Berkins, Sacayán, and Wayar—and before them, Nadia Echazú, who built this country. It was incredible, but also unprecedented, to live in a country with such powerful women leaders all together. That doesn't have to be repeated. Back then, we were dreaming of a country because we believed there was a planet with a future. And today we don't know if there is a future. So, how do we return to being little people dreaming under the abyss of feeling that there is no future?”

This implies new political challenges, but also emotional and spiritual ones, so that whatever comes next finds us on our own agenda. And I don't see that in our leadership or our political parties. I think art is slowly, very subtly still, beginning to raise some questions about this. And we must go in that direction. We must follow art. Not only to become artists, but to become, in any case, more creative people, which is what this era needs.

Books, schools, childhoods and other kinds of success

Susy Shock's latest book, La Loreta/Pibe roto , was presented at the last Book Fair, but Crianzas – Historias para crecer en toda la diversidad (Upbringings – Stories to Grow Up in All Diversity ), published in 2017 by Muchas Nueces, remains her text most closely related to children and schools. “That book originated as a radio program, in three-minute segments that interrupted the programming of national radio stations,” she explains. The idea came from the La Vaca cooperative and became a fundamental educational tool. “It was the teaching profession that embraced it and brought it into the classroom,” she reveals.

The book, in which a transvestite aunt speaks—from the love she feels for her nephew Uriel—to families, schools, and neighbors about the importance of letting ourselves be who we are, allowed for the introduction of profound debates, such as the use of the word "trava" instead of "trans woman," with accessible and everyday language.

“What’s exciting is seeing how the children have embraced it. Sometimes they come up to me and ask me to sign the book with their new name, after they’ve transitioned. They bring it to me and want me to sign it again with the same handwriting, but with their chosen name. That touches me deeply,” she shares.

Crianzas was also a self-management tool: thanks to its sales —which do not appear in rankings or cultural supplements— it financed Marlene Wayar's first book, Travesti, una teoría lo suficiente buena (Travesti, a good enough theory), published by the same publishing house.

“Those are our small but significant victories. Success, for us, has another name: it’s called community,” Susy proudly emphasizes.

This interview was originally published in our partner publication, Tiempo Argentino..

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.