Queer resistance in the Embera Katío community: art and political organization

Trans women and gay Embera Katío men from Alto Sinú, Colombia, suffer patriarchal violence in two ways: from criminal armed groups and from their own community.

Share

Trans women and gay Embera Katío men from the Alto Sinú region of Colombia suffer patriarchal violence twofold: from criminal armed groups and from their own community. From imprisonment to spiritual “therapies” to “convert” homosexuality, the forms of coercion are varied and justified by ancestral knowledge. But their resistance practices are also powerful, and art offers a path to identity and organization.

It's 10:00 a.m. in the municipality of Tierralta, Colombia, and the sun beats down fiercely on the entire Andean-Caribbean landscape. Leo gets off a motorcycle taxi and, before crossing the street, looks both ways. The town's corners are crowded with farmers and Embera Katío indigenous people, all waiting in line to receive service at government offices. Leo wears a white t-shirt with a rainbow print and walks upright, taking short, purposeful steps. Mockery and bewilderment appear on the faces of passersby. Two men ride by on a motorcycle and shout "faggot," then ride off laughing. Leo, who identifies publicly as a gay indigenous man from the Embera Katío ethnic group of Alto Sinú, is heading to his office in the center of town, from where he coordinates the Ojurubi LGBT indigenous collective. There, other gay Embera boys await him to give him several meters of colorful fabrics, which he will give to his mother when he travels to his home in Amborromia, an indigenous community located next to the Sinú River.

Ojurubi, which means “to open paths” in the Embera language, is an LGBT collective in Tierralta, made up mostly of Embera Katío Indigenous people (primarily gay men, trans women, and lesbians), who face racist and patriarchal violence daily for existing/inhabiting a dissident body. While Ojurubi was born out of the urgent need to create a safe space for LGBT Embera Katío people and to provide human rights education, the daily reality of homophobic and transphobic violence remains a constant presence in the municipality of Tierralta.

This municipality, located in the department of Córdoba – in the Caribbean region – has historically been an epicenter of the Colombian armed conflict and intense agrarian struggles due to profound inequality in access to land. Guerrilla groups, paramilitaries, and criminal gangs have primarily affected the civilian population through forced displacement, targeted killings, massacres, land dispossession, the laying of antipersonnel mines, and more recently, the practice of confinement. Added to this are the socio-environmental conflicts generated by the Urrá hydroelectric dam, which impacted the Sinú River, along with Indigenous and peasant communities.

Within this turbulent context of extractivism, armed conflict, organized crime, and drug trafficking, being gay and Indigenous becomes a matter of survival. The vulnerability that permeates and constitutes all bodies increases disproportionately for people like Leo, who must confront the patriarchal and racist violence of the capunias (non-Indigenous people), the armed actors present in his territory, and the Indigenous traditions of his community, which are sustained by an intricate patriarchal structure. But in this story, humans are not the only protagonists; the river, along with other elements of the landscape, also shares the experience of pain and resistance with the Embera Katío Indigenous communities.

The Embera queer memoirs begin in Do

Do in Embera means river water. This vital substance is one of the main elements in the landscape of the Upper Sinú, along with the tropical rainforest and the mountains. The Embera Katío territory of the Upper Sinú is situated in a watery geography, which also includes the Nudo del Paramillo Natural Park, an important biodiverse area and one of Colombia's main river systems. In the Paramillo mountains, one of the protagonists of this story originates: the Sinú River, which, according to an Embera myth, arose from the collapse of the sacred Jenené tree. The Sinú River (Keradó in the Embera language) was born specifically from the trunk of this mythical tree; its course runs from south to north, crossing mountains, floodplains, hills, and valleys, until it empties into the Caribbean Sea. Historically, the Embera territory has been fragmented due to colonization, the hostilities of the armed conflict, drug trafficking, and extractive industries. Water is one of the few things that not only unites a territory, but also binds the past, present, and future together. Leo was born and raised in Amborromia; his childhood memories are nourished by the golden waters of the Sinú River.

"My childhood was always by the river, because I liked to play there with my friends, my cousins, and my little brothers. I think the Embera people like to live on the riverbank because they are always playing. Children's childhoods are always on the riverbank, playing, making little clay figures, so that's how I grew up."

This river, teeming with fish, plants, and spirits, sustains life in the region, providing food, facilitating navigation, and offering toys for children. Daily life there is amphibious, a constant interplay between land and water, dry and wet, firm and soft, flat and deep. Water extends its reach over reality, imagination, and dreams. However, this daily life has been disrupted since the construction of the Urrá hydroelectric dam , the widespread planting of coca, and the deposition of landmines. Leo still vividly remembers seeing the first time they built the dam that would "trap" the river, dividing it in two. He used to travel downriver with his family to Tierralta on rafts, but since the dam was built, the landscape has been transformed, along with river access and food security. This is because the biological cycle of fish such as the bocachico, one of the staple foods of riverside communities, was interrupted.

But water has also played a key role in the exploration of gender identities and desire among Embera gay men. When Leo went down to Tierralta with his family and they passed by a makeshift stall selling toys, he didn't want balls, soldiers, or cars; he wanted a doll. But his mother refused to buy him toys that only girls could use. So, whenever he could, he would go to the riverbank and make his own toys out of mud: "We made the little clay dolls imitating the Barbies we saw in Tierralta." When Leo finished playing, he would hide the dolls under the canoe because if he took them home, he would get a stern scolding from his mother, who always reprimanded him for having different tastes than the other children.

Leo fell in love for the first time with another man deep in the jungle. “Since I was eight, I felt attracted to boys. So when I saw him, that boy was the prince of my life.” The young man, from Zambudó, another Embera community, had come to Amborromia because of security problems in the area. The Indigenous guards and communities were trying to survive the hostilities of paramilitary groups, the FARC guerrillas, and the Colombian armed forces. Despite ancestral norms that prohibited love and pleasure between same-sex couples, Leo employed various amorous strategies to reach the man he desired. The landscape allowed for the blossoming of a gay eroticism. Amid the crossfire of war and the machismo of the Indigenous culture, the scene of two teenagers making love is an act of resistance.

"The river and the jungle were accomplices in many ways because we were always waiting for our chance to escape. In Amborromia, there are many very old mango trees. They're very thick, with very thick roots, and that was our opportunity. So, when people gathered with the elders or the wise ones, we would escape behind the mango trees. We always headed that way and stayed there. I always escaped to the river. I would tell my mother in the late afternoon, 'Mommy, I have a stomachache. I want to go to the river.' Then my mother would give me permission. Well, I would go, but it was to meet the boy at the river, and sometimes I would say I was going fishing, but I wasn't going to fish; I was going to see him."

Like Leo, Dokera Bailarín, a young Embera Katío trans woman, began her process of exploring and affirming her gender identity and sexual orientation within the biodiversity of the Nudo del Paramillo Natural Park. Leo refers to Dokera as "the mother," a title she has earned for being the first visible Embera Katío trans woman in the Alto Sinú region. Dokera, in the Embera language, means "water and the aroma of flowers." She crafted her name herself, drawing on her grandmother's wisdom. She explains that in renaming herself, she wanted to highlight feminine delicacy and the scents of nature in the Alto Sinú. Dokera was born in the Cuti Indigenous Reserve in Unguía, Chocó, but due to the intensity of the armed conflict, she was forced to flee to the community of Nejondó in the municipality of Tierralta.

I grew up in Nejondó with my family. I played modeling a lot; we invented clothes with my mother's sheets and shawls. We built a runway with planks and played beauty pageants there. It was very strange because we didn't see that on television; we lived in the countryside.

For Dokera, games helped her explore and reaffirm her gender identity, discover herself as a woman, and explore other identity, bodily, and aesthetic possibilities beyond those offered by the binary system of her ancestral community. Every time her mother found her having fun, she would say, “Men don’t play house.” However, she persisted in building a house within their home where she could play out feminine roles. “We built the little houses with sheets and wooden tables that my grandfather made. There, I imagined I was a queen, Queen Cleopatra,” she says, laughing as she draws a river without fish. She also enjoyed mending her sister’s dolls. Embera women make rag dolls from scraps of fabric they obtain from the parumas (a type of bird).

The other part of her childhood was spent in Kapupudó, another Indigenous community located beside the Sinú River. Day after day, she discovered herself as a woman, while the eyes of her family and ancestral authorities intensified their control and surveillance of her body. By age 12, it was clear to her that she was only attracted to men, but loving and experiencing sexual freedom comes at a very high price in contexts where human rights are nothing more than an abstract concept, and where the rule of law is nullified by criminal governance. Dokera made her face a territory of resistance, filling it with colors to highlight the beauty of an Indigenous woman. But how can one construct femininity in the middle of the jungle, if there are no makeup stores or beauty salons? Through her imagination, she appealed to the nature of the Paramillo region, harnessing it as a generative biotechnology.

"When I was 13, I would wait for my mother to cook over a wood fire so that the pot would turn black, and then I would take some of it to paint my eyebrows and eyes. I would paint my lips with the achiote plant, making them really red. When my family arrived, I had to take it off or they would beat me."

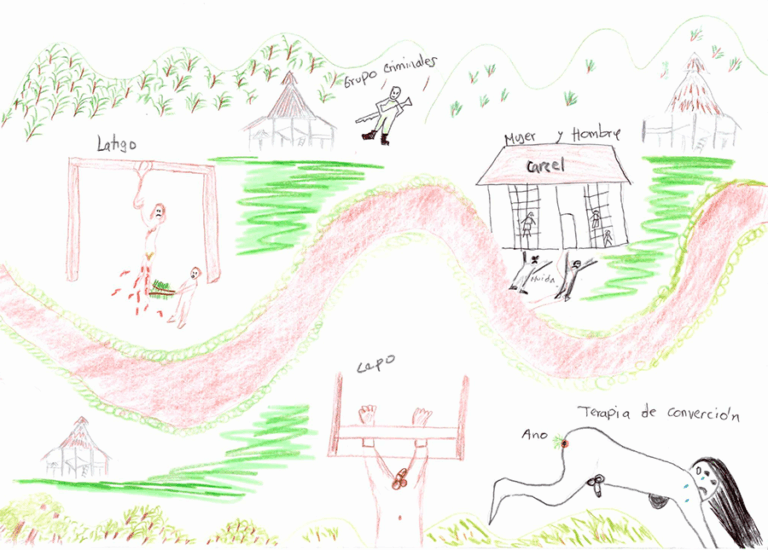

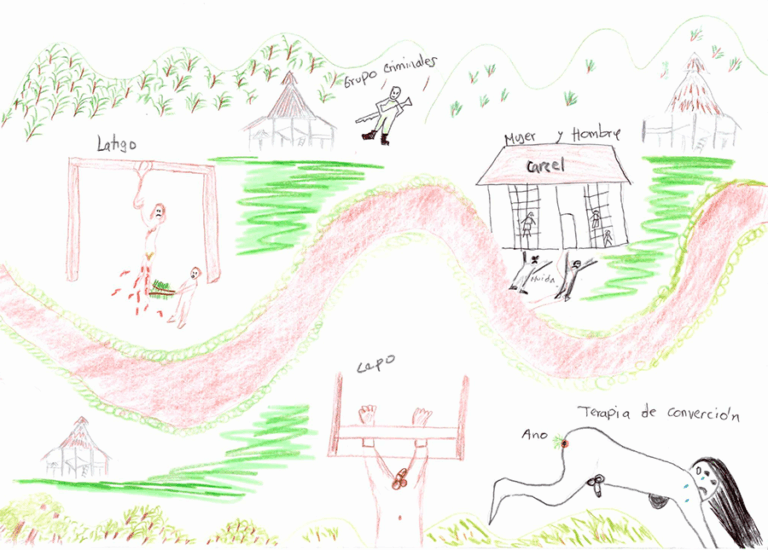

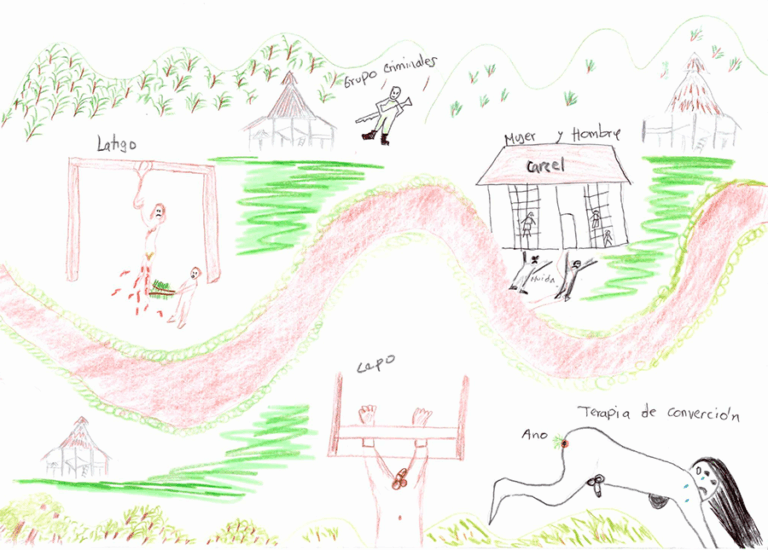

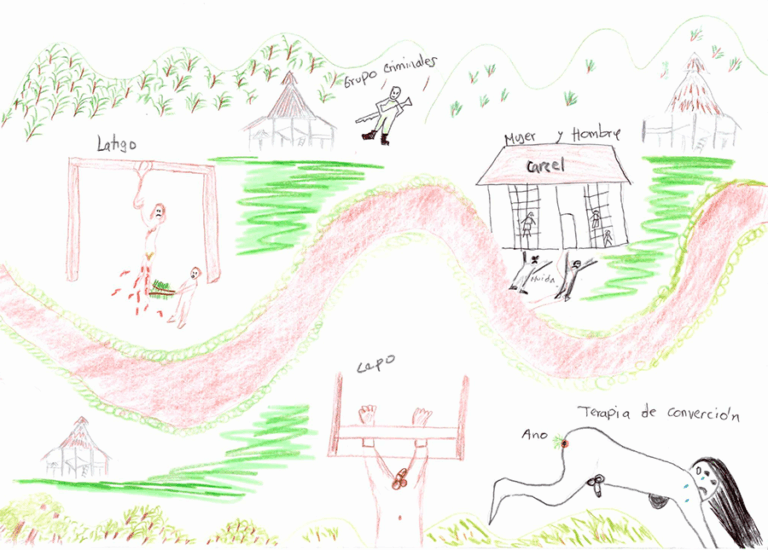

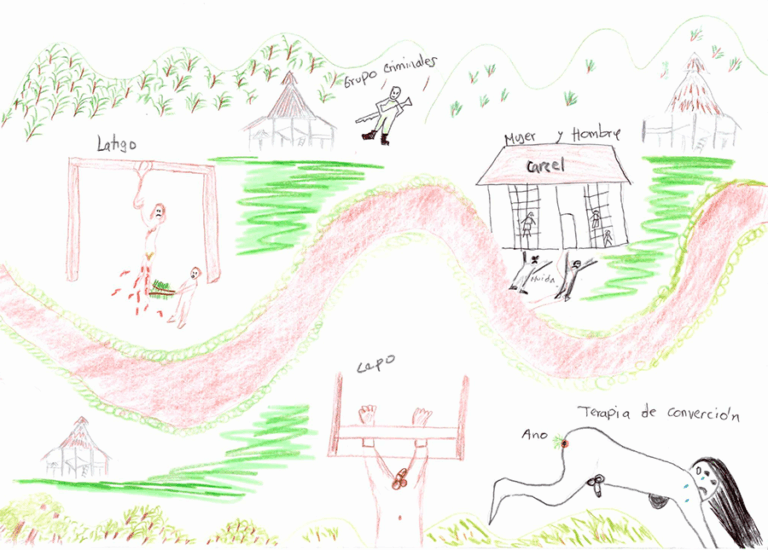

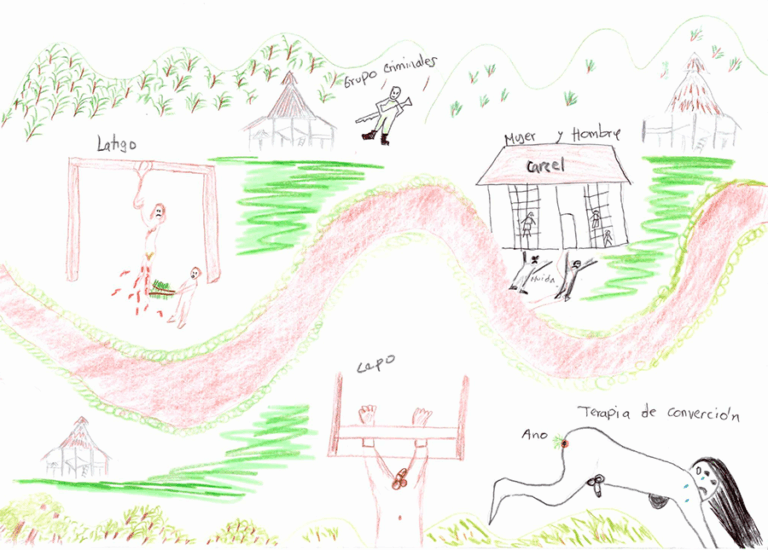

Meanwhile, Dokera recounts how she obtained her first makeup, sketches the body of an Embera woman, and draws herself. From the waist down, the woman's body transforms into the Sinú River, surrounded by fertile fields inhabited by farmers and Indigenous people. At the top of her torso, the woman is chained, her arms bound. Her eyes are filled with tears. Dokera weeps as she draws herself weeping. In the drawing, the woman holds a sugarcane press (Ewadaura yô) between her neck and chest, a figure from the kipara (a ritual instrument) used by cisgender women during menarche to participate in the female initiation rite "jemené," a traditional dance of the Embera culture.

"We don't have as many rights as men, and now even more so as the LGBTI population. I feel like we're tied down by the lack of decent work; we're marginalized. We see our hope in nature and water."

The trees, the river, and the mountains are not mere landscape decorations; they possess a vital and political agency that connects with the Embera people through mutual and collaborative work. In the Paramillo mountain range, the relationship between humans and nature is more complex than it seems, even when modern thought imposes its logic of binaries and hierarchies. In this space, for some, the construction of gender and desire is possible thanks to multispecies work, ranging from complicity to cooperation between humans and non-humans. Thus, Embera queer people like Leo or Lucy do not ignore the vital role of nature, but rather give it a central place in their identity, bodily, and affective processes. Clearly, this relationality is connected to the logic of life, in contrast to the criminal logging carried out by the Clan del Golfo—now known as the Gaitanista Army of Colombia—as a recent journalistic investigation revealed. In the face of the destruction of the forest and the tropical rainforest, the display of a fruity, woody eroticism among mango, caimito, lemon, orange, mandarin, sapote, borojó, achiote, ceiba tolua, cedar, abarco, carbonero trees is also an act of resistance that puts criminal economies and the hetero-patriarchal order to flight.

Paradoxically, the same nature or Mother Earth ( papa enjua in the Embera language) to which ancestral authorities appeal to impose the natural/divine division of the sexes, heteronormativity, and the traditional family model, is the same nature that makes it possible to dismantle all these totalizing social structures. The river then washes away the marks of the sex-gender system, violently inscribed by institutions like the family or ancestral authorities. The river hydrates the parched flesh of the heart and allows desire to bloom like an orchid on the branch of an abarco tree. The tropical rainforest thickens its walls, making its center a safe haven for two men to love each other. From the branches of a bixa orellana plant sprout fruits with seeds that burst with carotenoids, reddening the lips of a life that dreams of becoming a girl/woman.

Conversion therapies to kill pleasure

The concept of the closet, or wardrobe, presents, among other things, a territorial logic. It is not the same to inhabit and come out of a closet in a rural area, an Indigenous reserve, a Black community, or in a middle-class neighborhood of Bogotá. Beyond the obvious distinction between inside and outside, there are also many ways of being both inside and outside. In the Paramillo Knot, the closet becomes a generalized yet localized geographical framework: places like certain riverbanks, groups of trees, and rocky outcrops, where the boundaries between inside and outside blur. The experience—part voluntary, part imposed—of coming out of the closet brought serious security consequences for Dokera and Leo. From threats and forced displacement to stigmatization and even torture, these are some of the experiences to which LGBTQ+ people are subjected within the reserves.

Sitting across from the main church in the municipality of Tierralta, a few meters from the Sinú River, Leo begins to let his memories overflow. The first person he remembers being punished for her sexual orientation and gender expression is named Bella, an Embera lesbian woman. Bella was first imprisoned in Dozá for six months because “she liked to work hard in the forest, wield a machete, and do men’s things.” Then they tortured her in the stocks because they saw that she wasn’t changing her behavior. According to Leo, since 2006, LGBT people have become more visible, which led armed groups to gather communities and begin pressuring Indigenous authorities to take action. The response was to implement measures of surveillance, persecution, and repression to restore moral order. For example, paramilitary groups that have been present in the territory coerce Indigenous communities into identifying LGBT individuals in order to subject them to corrective punishments. If these communities do not comply, the groups intervene through forced recruitment practices, including, in some cases, sexual violence. Another gay Embera man comments:

The armed group recruited boys to work as men. We never, ever felt protected by the councils or the community. There was a mutual agreement between the armed actors and the community.”

Dokera was first taken to the stocks—a dungeon within the community—when she was discovered having an erotic-affective relationship with a man; it was her father who turned her over to the Indigenous authorities. “I spent two days in the stocks; I came out unable to walk. My leg swelled up because the blood wasn't circulating, and my skin started turning black.” After that event, the closet as a strategic refuge shattered. There was nothing left to hide, but much to defend. Dokera began to present her made-up face in the public life of her reservation. It was through her face that she challenged the normative constructions of gender, despite the beatings, the mockery, and the shouts. The implementation of her sexual freedom and the autonomy to create a desired body resulted in her imprisonment on three occasions. Even as her body was being subjected to the disciplinary powers of patriarchal ancestral traditions, Dokera continued to radicalize her existence.

Nature was stronger than me. It was something I could no longer hide. I loved wearing makeup, being feminine, so they kept beating me, but I didn't care anymore. Then they put me in jail there in Kapupudó. The jail is a big hole in the middle of the mountains; above the hole there's a cemetery, and the Sinú River flows underneath. The jail is dark, very cold, and there are a lot of mosquitoes. In the jail, there were men who beat their wives, and women who were unfaithful to their husbands.

The third corrective method to which LGBT Embera people are subjected, in addition to the stocks and imprisonment, is conversion therapy based on magical-spiritual knowledge. These therapies are performed by jaibanás , possessors of ancestral medical knowledge and magical powers. The jaibaná is a key figure in the Embera world: they are doctors, sages, poets, and teachers; they hold the key to accessing other spheres of reality beyond what is immediately perceptible. Leo comments that children and young people who do not “change” their sexual orientation and gender expression after having been in the stocks and imprisoned, and even after “being hung from a tree and whipped with gourd sticks,” are generally taken by their own mothers to the jaibanás to be “cured.” Although Leo had to be forcibly displaced from his territory to avoid being punished and tortured, he is intimately familiar with the cases that systematically occur within the Embera reservations in relation to conversion practices:

The shaman believes that homosexuality is a spirit and a parasite, so they use medicinal plants from the forest. They take the roots of large trees and mix them with hot chili peppers. They also use a fruit that they crush; when all of it is mixed, it releases a vapor. They insert this into the anus. Two cousins underwent this treatment. The family gathers, and in front of everyone, they tie the boy's arms and feet so he will submit to the treatment. Then, with their hand, they insert it into his anus. The person screams in pain. They leave it inside for 20 minutes and then remove it. They repeat this up to three times.

When Dokera learned that her family was going to subject her to the conversion therapy, she decided to escape by throwing herself into the Sinú River at night. She swam several meters and then got out of the water to continue her journey toward the town of Tierralta. The anus is a place within the body's geography whose uses, senses, and meanings have historically been contested. The fact that the conversion therapy is located in this area, and that it is often believed that "the spirits and parasites of homosexuality" reside there, is nothing more than a cultural strategy based on patriarchal logic that seeks to manage the pleasures of this undeniably erogenous and political space, according to heteronormative sexuality that only legitimizes the penis/vagina relationship. For Leo, the torture practices used during the conversion process "aim to kill pleasure," therefore, the effects are not only physical, but also emotional and spiritual.

I asked the boys how it feels after that. They recently made me cry at an Indigenous meeting when I told them about it. They are affected, trying to heal. The boys who have gone through this treatment no longer feel satisfied, they don't feel that passion. They no longer feel pleasure. They tell me: "I can have sex, but I don't feel anything."

While these practices are not usually based on “scientific” knowledge, their legitimacy rests on the ancestral nature of traditional shamanic knowledge. However, gay Embera Katío shamans maintain that far from achieving their objectives, these practices cause traumatic wounds to the body and mind, a fracture in pleasure and desire. But this story isn't all black and white. There are also gay shamans, like Leo's grandfather, who didn't have the opportunity to come out as his grandson did. Most gay shamans oppose their community's view of sexual and gender diversity.

My grandfather was a gay man who never came out of the closet, and he was a jaibaná (shaman), and he passed everything down to me because I'm also a traditional healer. So I had a question: why, if my grandfather taught me things, did he never tell me that homosexuality can be cured with plants? That's why I went to find another gay jaibaná and asked him: "What do you think? Do you believe that's parasitic, from your perspective? Do you believe it's the way heterosexuals say it is?" He told me no, that it's not like that, that homosexuality isn't cured with a plant, it isn't cured with spirits, it isn't cured with treatments.

The path of organization

For Dokera, the worst punishment an LGBT Embera person can receive is expulsion from their territory and forced into the city, where they often hear the expression, “Oh, besides being an Indian, you’re a faggot!” In the city, Dokera missed the sound of the river, the birds, and the flavors of the jungle. When he escaped his community, he managed to survive thanks to a gay cousin who lived in the municipality of Tierralta. This cousin resided in a house that served as a clandestine refuge for gay and trans Embera Katío people. Thanks to these underground networks of solidarity among gay people, many Embera managed to survive the hostilities of their environment and even suicide itself.

There were other refugees in that house who had also fled. About ten of us lived there, but the owner didn't know it was a shelter for gay people. It was a clandestine shelter. But when they found out that gay men and trans women were living there, they punished everyone and took them to the Tierralta municipal jail. I had to move to Montería, and Córdoba Diversa supported me there. If that shelter hadn't existed, I feel like I would already be dead. I feel that's why there were so many suicides among the Indigenous LGBT population, because we didn't have that shelter.

In response to the rise in homophobic and transphobic violence, Leo decided to move to Bogotá in 2016. There, he participated in the first LGBT Pride march and began connecting with NGOs and collectives dedicated to defending the human rights of sexual and gender minorities. He realized that what his community needed was the support of a collective conceived from and for their specific needs. In 2018, with a mouth full of fear and a heart full of hope, he returned to Tierralta to seek support from institutions and grassroots organizations that could serve as allies in his struggle. In 2019, Ojurubi was founded as an organization with the purpose of eradicating torture and conversion practices within Embera Katío territories, but also with the mission of facilitating the return of Indigenous gay men to their communities. From the outset, they recognized that their primary battleground had to be within the Indigenous reserves. So far they have managed to have an impact in three communities: Amborromia 1, Amborromia 3 and Bocas de Río Verde, where they have talked with the ancestral authorities and reached non-violence agreements.

Ojurubi drew upon the artistic practices of Neka (weaving), kipara (face and body painting), and Ûntakãri (dance) to develop resistance strategies that would allow them to return to their territories to bathe in the river, eat fish with plantains, and smell the mountain flowers. Dokera challenged the authorities of their reservation, proposing that gay men could be translators, poets, dancers, and provide psychosocial support to the communities. Thus, to transform perceptions and stereotypes, Leo explains that spaces were created to train communities, conduct human rights education, and make LGBTQ+ people visible through alternative narratives.

We would arrive and say: look, we make bracelets, we'll help you sell them. Look, this boy paints. Look, we have a dance group, we'll teach them. Everything was free. Look, I make dresses, so we gave them away.

Faced with verbal and physical aggression and the force of the harm inflicted, the Embera queer people have wielded only one weapon: art. For Leo, “The best weapon we have ever taken up is craftsmanship; craftsmanship was the machete that saved us from everything.” Thus, art served to transform the languages of hate and build legitimacy within their ancestral territories. Other allies, besides institutions and international cooperation agencies, have been the river, the rainforest, and the mountains. The nature of Paramillo has enabled the flourishing of desire, escape, and salvation in many human lives. Paradoxically, the same nature that is used to torture the body and deplete the pleasures of the anus is the same nature that lends its textures and fluids to reaffirm life. In this way, resistance is also a collaborative effort between humans and non-humans, an inevitably multispecies endeavor. This is despite the fact that, within the Embera political imagination, the Sinú River is dead, a consequence of the ecocide caused by Urrá, but it is also an enormous watery grave where armed actors have systematically disappeared the bodies marked by war. Therefore, reading this from these biogeographical frameworks, trapped by the death logic of extractivism and armed conflict, reveals not so much ambivalence as vitality—in this case, driven by queer and transvestite desire—that fights against apocalyptic discourses and embraces hope without falling into the traps of resilience and adaptation to chaos as a sacrificial preparation for the end of the world.

Dokera finishes the drawing and insists on leaving the river without fish. Behind her chained body, she has drawn the Urrá Dam, which also holds the river captive. Outside, the moon now captures the high Sinú landscape with a dark vehemence. Since fear still lingers, she decides to go home, but not before commenting: “I dream of a safe haven that always has its doors open for us, that accepts and respects us. That LGBTQ+ people occupy spaces in the workplace and receive an education. I dream of being a famous designer with an exclusive collection for queens, that my collection can be shown in Paris.”

This journalistic piece was originally produced and published in the third edition of #CambiaLaHistoria, a collaborative project by DW Akademie and Alharaca, promoted by the Federal Foreign Office. Learn more about the project and other stories at https://cambialahistoria.com

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.