Mónica Astorga, the "nun of the trans," left the Church but not solidarity

Sister Monica became known in recent decades for her fight for the rights of transgender and transvestite women. From Neuquén, where she was Mother Superior, she campaigned for support and access to housing, which materialized in a cooperative. She had the support of Pope Francis, but it wasn't enough: her defense of sexual diversity led to her estrangement from the Church, though not from her faith. Today she lives in Buenos Aires, studied podiatry, and continues her vocation of service.

Share

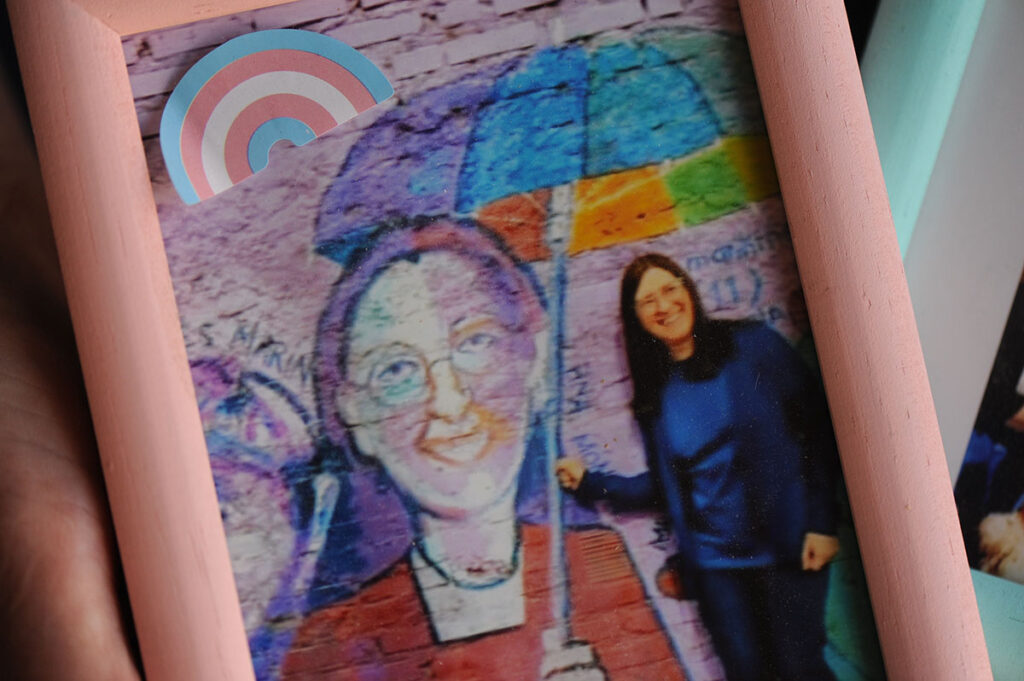

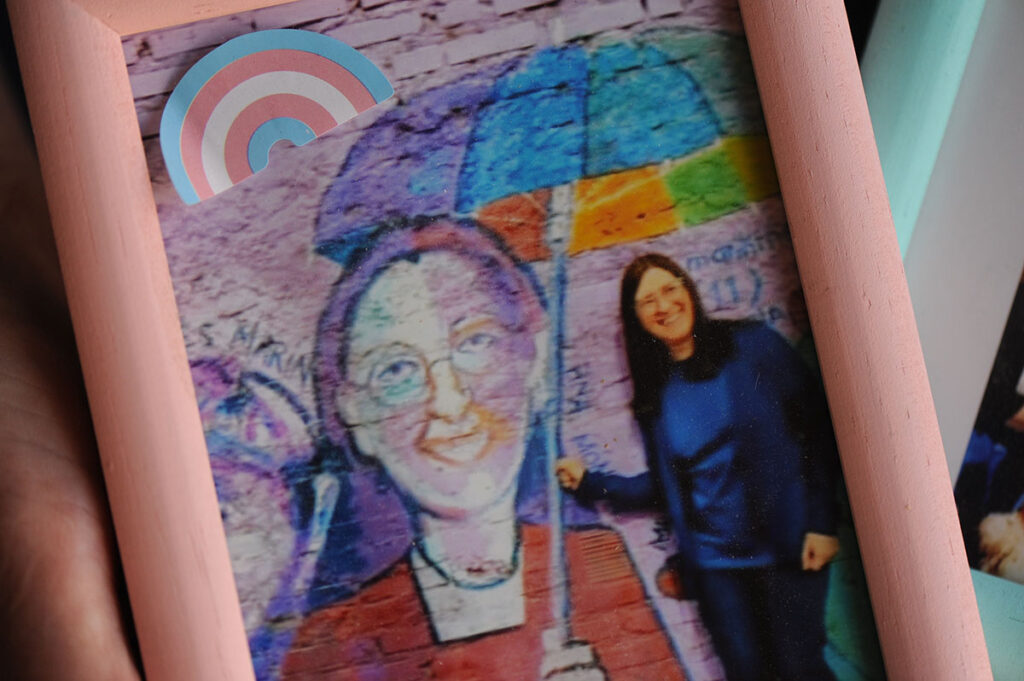

Mónica turns the corner and appears on a sunny Saturday in January on Rivadavia Avenue. She's lived in the Flores neighborhood of Buenos Aires for two years. Her hair is tied back, and she's wearing a blue t-shirt, denim shorts, and beige sandals. Her look and petite stature shouldn't attract attention, but she has one feature that sets her apart from the other passersby: a big smile. It's a gesture she wears most of the time. She's traveling to the Borda Hospital. She arrives around 8:30 a.m., carrying a pack of ten cigarettes and alfajores (a type of Argentine cookie) of different flavors. It's the birthday gift Marcela, "Rompecoches" (a play on words combining "car" and "rompecoches," meaning car), a 54-year-old trans woman who has been hospitalized in the public hospital for six months, asked for. When Mónica arrives, Marcela is already awake, although she didn't go to breakfast like the rest of her wardmates, all of whom are men. "How long are these going to last you?" she teases as she hands her the package.

Marcela is the antithesis of Mónica. She's enormous and has pronounced curves. She has a thick mane of curly hair, a perfectly upturned nose, and V-shaped eyebrows, reminiscent of the actress Graciela Borges. She earned her nickname one day when, in a fit of rage, she smashed a police car during one of the frequent fights she and her companions had with the police while working as a sex worker on the Pan-American Highway.

She's lying down and after a while she asks us for help to sit up. She does it carefully: her tail hurts when she sits down.

"Because of all that stuff they've put on," the former sister reproaches her.

"We didn't know, Monica. Anyway... this tail has given me so many things." She laughs. She has a dry sense of humor. She recently suffered two strokes. She moves with difficulty, although she's feeling better than she did a few weeks ago. She's in good spirits, smiling and speaking with enthusiasm.

When Mónica says goodbye and leans in to kiss her, Marcela asks for “two, like in Paris.” “Her friends say she used to be mean. Imagine, they called her 'Car Breaker.' But she’s changed a lot. She texts me 'I love you.' I don’t think they could ever imagine it.”.

A clean bed to die in

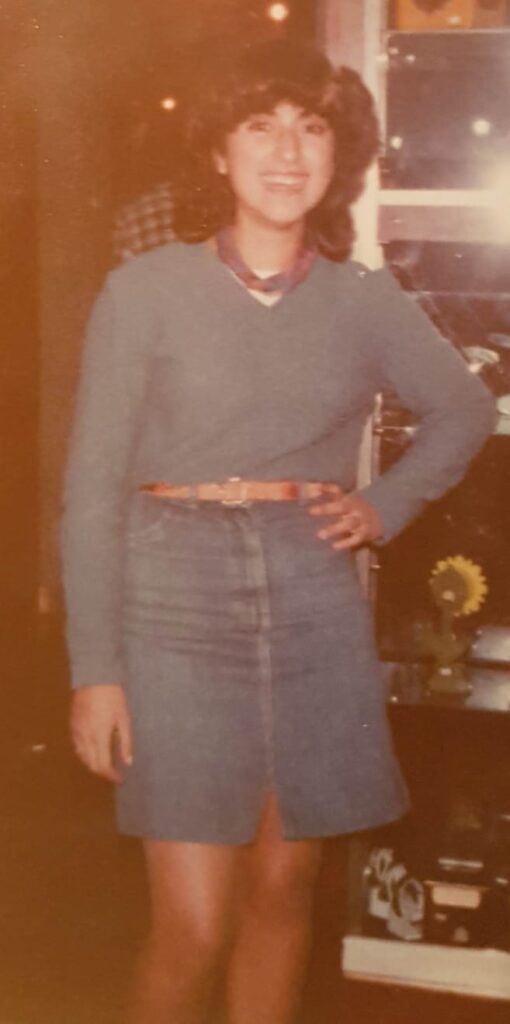

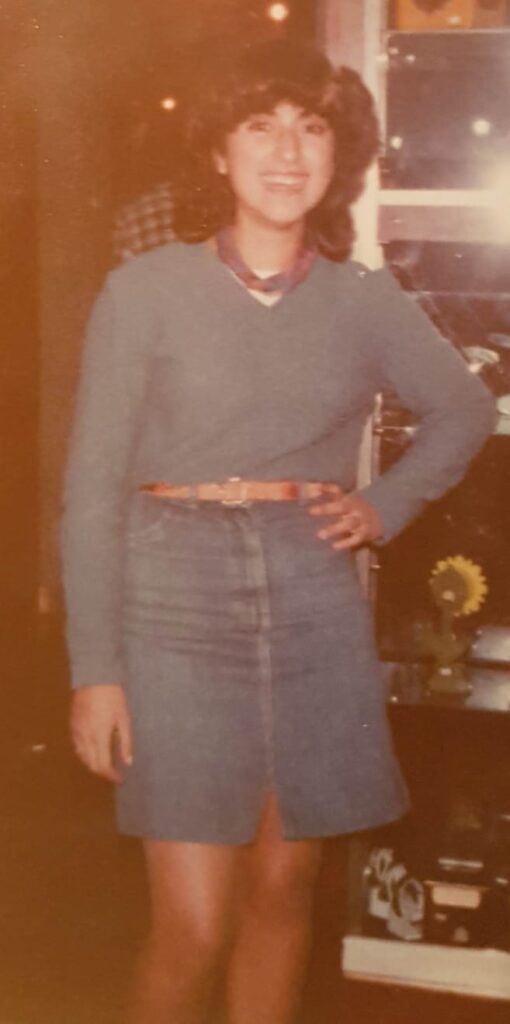

Mónica Astorga Cremona was born on December 3, 1964, at Piñero Hospital in Buenos Aires. When she was three, her parents separated, and she went to live with her mother in Rauch, in the Buenos Aires countryside. She is 60 years old, but she doesn't look it; she has hardly any wrinkles. Underneath her habit, she was able to control the curls she never liked. Today, she wears straight, black hair, the closest thing she could have to a veil. When she told her family she had left the convent, they said they wouldn't be able to see her without her habit. To this day, they haven't.

She dedicated most of her life to service within the monastery run by the Discalced Carmelite Order in the province of Neuquén, where she served as Mother Superior for two three-year terms. Today, she continues her vocation outside the Order: forty years after entering the monastery, she was forced to request to leave. She was a cloistered or contemplative nun, meaning her life was confined within the monastery walls, where she dedicated herself to prayer and the pursuit of union with God. Previously, they were called "cloistered nuns." Throughout her life, she accompanied people with substance abuse problems and those whom no one else wanted to visit, such as those sentenced to life imprisonment. She did this by sending letters to them in prison. Then, in 2006, she met first one, then four, and finally dozens of transvestites and transgender people in the city of Neuquén.

“One day Romina, a friend from San Juan, came to us and told us that she had gone to the Lourdes church to give her tithe, but they wouldn't accept it because she came from prostitution. There she met a nun and a priest who introduced her to another sister: Mónica. And she wanted to meet us. We… you can imagine. What could a nun do for us, who were constantly running from the police or getting arrested? But we went to meet her. I'm very Catholic. There were four of us: Victoria, Luján, Romina, and me.” The speaker is Katiana Villagra, a 62-year-old trans woman. She arrived in Neuquén when she was 22 after wandering through different parts of Buenos Aires. She didn't like it. The heels and stockings that had been pristine on the asphalt became worn and faded on the side of the road, with the cobblestone streets and the relentless wind. It was one of the first to arrive, but soon it was filled with transvestites and trans people from different provinces: there were more from outside than from Neuquén itself.

—Why were they going to Neuquén?

"In Buenos Aires back then, they'd keep you detained for 30, 60, 90 days. We had no rights. The good thing about Neuquén was that they didn't arrest us. And if they did, the operation only lasted 24 hours. Later on, there was a time when they started arresting us every day. But by then I was already a citizen of Neuquén and I had chosen this place. If you drink water from the Limay River, you're never going to leave.".

Over the years, Katiana continued working on the streets, got breast implants, and considered herself an activist. She was 40 years old when she met Mónica.

—The nun was tiny, but beautiful. The first thing she asked us was what our dreams were. Luján told her she would have liked to finish her degree and study to be a chef; other friends said they wanted to be hairdressers; and another was studying massage and things like that. I remember when she asked me, I told her I wanted “a clean bed to die in ” I hadn't realized how much what I said affected her. At that time, we were in the middle of the AIDS epidemic, and at the hospital, when they couldn't do anything more for the women with HIV, they discharged you and gave you a hospital bed so you could go home and die. And we didn't have homes! So you went to another friend's house. We'd put the IV in the place where we were smoking, doing drugs, drinking alcohol to get ready for work. And the friend was there among us. Every time I saw the sheets, they were dirty. That's why I wanted a clean bed to die in. Because I was already of age.

At 40, Katiana already felt close to death. She knew that the average life expectancy of the trans community to which she belongs was—and still is—around 35 years. Today, at 62, she is a survivor.

That conversation sparked an obsession in Monica.

Hard years

At seven years old, she first felt the desire to become a nun. She lived with her mother, María Vilma, in a dilapidated, old house with high ceilings and tiled roofs. Her mother worked in a restaurant in Rauch. While her mother slaughtered and plucked chickens, Mónica peeled potatoes, which piled up in drawers throughout the house. Because she wore a new school uniform and carried new school supplies every year, the school was unaware of the situation at home, where several times a week they didn't have enough to eat. It was a gift from her father, who sent her just enough money—no more, no less—once a year to buy what she needed for school. She also saw him once a year, for the holidays. Although he sometimes sent her toys, Mónica made her own. In one room, she created a pharmacy; in another, she ran a shop; and in the dining room, she played teacher. The neighbor's antenna had been placed in their yard. He would climb it until he reached the roof of his house, from where he would spend hours observing the town from above while making crosses with a string.

“Those were difficult years; we managed just the two of us. She was an alcoholic. I begged her not to die because I didn’t know what I would do alone. We lived with very little. And even so, she always told me, ‘If someone comes to this house asking for something, they can’t leave empty-handed.’ When I told her as a little girl that I wanted to be a nun, she listened and started sending me to live with two sisters who worked at a hospital. I would go and play with them,” she shares, sitting in her living room while preparing mate.

Things didn't get any easier after that. When she finished elementary school, she went to live with some relatives in the Flores neighborhood of Buenos Aires. They told her she wouldn't lack for anything.

“ It was all a lie. I became their servant. They gave me money that wasn't enough to buy school supplies, so I started working. I gave them half my salary and used the rest for my studies. Those were years of being very sad and angry, but I always put on a brave face, with a smile. I don't think anyone suspected a thing. A friend from that time asked me if I wanted to join a group at a church. I told her I didn't want to know anything about it; I was angry with God. She insisted. For me, since I was little, the church had been a refuge, and when I finally went, I felt the same way I felt when I walked into the church in Rauch,” she says.

That year, the religious group she started attending was traveling to Neuquén. She didn't tell anyone in her family and went there by train. "When I arrived, what struck me was that it was a very, very humble neighborhood," she says.

The convent she arrived at was the Monastery of the Holy Cross and Saint Joseph of the Discalced Carmelite Order. Founded in 1982, it was the first convent in Neuquén dedicated to contemplative life. It consisted of two small prefabricated houses where an austere daily routine was followed. Each nun had a room and a fruit crate in which to store her clothes. Mónica, at 20 years old, went to live in a place like this. That December, she had the best Christmas of her life.

“I felt like it was my place, like I had lived there all my life,” she says.

Twenty days after entering the convent, she was informed that her mother had been hospitalized urgently due to a hemorrhage. By that time, her family was supposed to have left her behind upon entering the Carmelite convent, but her Mother Superior insisted that she go and see her.

“In March I traveled. I was wasted away: uterine cancer. That's when she told me: 'I see you happy. You're in the place you always wanted to be.' She was the only one who knew what I wanted. Everything I am is because of my mom.”.

Convent life

At the convent, Mónica woke up at 6:30 in the morning. She and the other sisters prayed together, followed by an hour of individual prayer. Then came Mass, breakfast, and the first part of her workday. They cleaned, made crafts, and sold Del Carmelo . They prayed and ate lunch together in silence. They washed the dishes and had an hour of recreation together. During this time, Mónica shared the news she had read the night before, mostly crime reports—a habit she picked up from accompanying prisoners. A short ten-minute prayer followed, and then they could go for a walk, rest, or read. She usually chose to walk, followed by a bath and a short nap before returning to work. They had community formation, a second hour of prayer, and a half-hour prayer together, with psalms and readings. To make the day shorter, they had decided to have dinner together, combining recreation with eating. The last prayer of the day, and then each would go to her room. “That’s when I’d start talking about trans people, about social media, answering things,” Mónica says.

When she entered the Carmelite convent, she vowed two things: that she would not lose her joy and that she would remain grounded. “For me, simply asking in prayer for 'all those who suffer, for the whole world' wasn't enough. I wanted to be able to touch those people. I wanted to bring their faces into prayer,” she says.

She began using her midday break to meet with the women. In those conversations, Mónica was deeply affected by their lives: the bullying at school, leaving home, the need to migrate to another province, the injections of airplane oil to enlarge their buttocks and breasts, the police harassment. She learned their language and particular sense of humor and adopted their codes. Her serene demeanor could quickly harden when the conversation turned into an argument. At those moments, the atmosphere would become tense. “How can you treat each other like that? You make so much effort not to be men, and in the end, you act just like them,” she would say to them, furious.

Incorporating technology into the convent was an odyssey. “When the whole email thing started, I was the first one to set one up. A sister had gotten hold of an old computer, and I asked permission for two friends who worked in IT to show me how. I insisted, and they put a computer in the dining room with a communal email account. Everyone could see it. I had a tiny cell phone that some relatives gave me in 2007. I told them I couldn't have it, and they told me to keep it hidden. Why did we have to live in hiding? They told you that 'the outside world would invade' you if something like that came in,” she recounts. Mónica's Facebook page became known to LGBTQ+ activists and journalists covering gender issues. In addition to connecting with the trans women who came to her, she kept a tally of the transfemicides, transvesticides, and transhomicides that occurred in the country. She religiously posted them every time she heard about a new one.

Following the death of Pope Francis, Mónica shared on her Instagram profile the first letter Francis sent her from Rome. It was in response to another letter Mónica had sent him along with trans women from Neuquén, who wanted to share their well wishes for this new chapter. He replied: “Dear Sister Mónica: Now, let's move forward… with prayer and the frontier work that the Lord has placed before you. Tell them from me that I do not condemn them, that I love them, and that from my heart I accompany them on life's journey, praying for them. But please, pray for me. Tell them that I am grateful they pray for me, and that Jesus and the Virgin Mary love them; they should not doubt this. I'll leave you now. Please don't forget to pray for me. May Jesus bless you and the Blessed Virgin Mary watch over you. Francis.”

“I feel like I was orphaned. I always told him he was my father, my pastor, my brother, and my friend. He accompanied me in this fight to make trans people visible. He received many of the girls, and he called others on the phone. He always told me, 'You can count on me.' He insisted that I tell them that God loved them, that they should never give up, and he had great respect for the LGBT community,” Mónica told Presentes.

The cooperative

With Katiana's words echoing in her mind, "a clean bed to die in," she began knocking on doors. Archbishop Marcelo Melani offered a dilapidated house, which Caritas renovated, so that the women would have a place to stay after leaving the hospital. It became filled with trans women and transvestites who gathered there to spend time together. Romina and Victoria opened a hair salon, and Katiana opened a sewing workshop: it wasn't a place to die, but a place to live.

During those years, Katy was able to leave the streets, but not alcohol. Every Christmas she would call Mónica crying, drunk. It was the impetus for another project. Casa Santa Teresita del Niño Jesús (Saint Teresa of the Child Jesus House) was inaugurated in 2019 in the city of Neuquén with the goal of promoting prevention and treatment programs to assist transgender people with substance use disorders. “It’s Mónica’s work that I will continue as long as I can,” says Kati, who now co-coordinates the institution and hasn’t had a drink in twelve years.

But Monica had another goal in mind. They needed a place to return to after work and training: a decent house where they could bathe, cook, and rest in a clean bed.

One day, Kati's words became a reality. On August 10, 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, the province of Neuquén inaugurated the world's first housing complex for transgender and transvestite women. The municipality of Neuquén donated the land, and the provincial government, under Governor Omar Gutiérrez, carried out the project championed by Mónica. It consists of twelve studio apartments and a multipurpose room, where twelve older transgender women live.

Those were months of happiness. The women, with their few belongings, began to settle into their new home and improvise living alone with neighbors. Mónica continued to welcome them, now with a slightly calmer heart. She knew there weren't enough houses for everyone, but it had been a big step. Christmas arrived, and together with the other Carmelite nuns, they prepared sweets with a message, which they delivered to every house in the neighborhood. There's a selfie that shows Mónica in the foreground with three sisters, all smiling, as they hand out the gift. "We spent a Christmas where I didn't know what was coming," she says.

Discrimination

On December 22, 2020, Bishop Fernando Croxatto visited Monica's monastery for a fraternal visit. "It's something that's usually done, different from the canonical visit that takes place when there's a serious case based on certain allegations," Monica explains.

After speaking with each of the sisters in the community, the bishop gave feedback on his visit on January 15. That's when his surprise began: he said that pastoral accompaniment was not part of the Teresian charism. In other words, the accompaniment Mónica was providing to transgender people was not appropriate for a contemplative life.

She traveled to Buenos Aires, where they lent her an apartment near Congress until things settled down. “I was in a very bad place; I fell into a depression from which it was very difficult to recover,” she says. In February, she had to return to Neuquén. She thought the Order had resolved her situation and that she would be able to live in the monastery again. “But when I went, they asked me to decide. It was either them or me. So I said I preferred that the community continue and that I would leave. They agreed. In the end, after much back and forth, only three nuns remained in the community. They said they couldn't sustain it, so the monastery closed.”

Mónica requested a transfer to the convent in Córdoba and stayed there for a year and eight months, until December 2022. After a series of questions —“This is not a trans house”, “You arrived with an empty shelf and started filling it with all your things”, “Your head has already been cut off”—, she made the decision to request a dispensation from her religious vows.

What she considered a betrayal on the part of the other sisters and the bishop in Neuquén, the closure of the monastery that she fell in love with at age 20 and in which she lived for four decades, the whispered comments and the objections to her work in the convent of Córdoba finally made her, before losing her faith, request to leave the Order.

“My heart feels broken and bleeding. It was not and will not be part of my desire or will to dispense with my vows as a Consecrated Woman to Jesus,” she posted on Facebook the day the Vatican accepted her resignation request.

Pioneer

Friar Miguel Márquez Calle is the Superior General of the Discalced Carmelites. He met Mónica when he was in charge of the Order in the Iberian Province of Spain. From then on, they met every time he visited Argentina and developed a friendship.

“I thought it was beautiful how it all began. Offering, with great respect, a space for listening and welcome, where they felt they were being treated well. From her own perspective… because she was a contemplative nun. She wasn't a nun living an active life,” she says. Because of her role within the Church, she travels to many places around the world, but on this occasion, she speaks with Presentes by phone from a street in Rome, near the Villa Borghese.

He believes that the support Mónica had been providing was well-received within the Order, but this depended on each individual. “I couldn’t say if there were people who weren’t so supportive or less accepting of the issue. Surely there were some,” he remarks. For him, what happened with Mónica’s departure is related to a trend he observes in various countries: that communities are dwindling, there are fewer and fewer nuns, and they can no longer continue. He doesn’t believe it was because of the work she had been doing with the trans community. “I haven’t heard anything about her being reported or criticized for her work. Perhaps there was something like that, but I can’t confirm it. I think it’s true that she has chosen a different path in life.”.

Within the Church, “work is being done, but it’s true that some view everything related to trans people with suspicion,” she explains. “ There’s a faction that can be more moralistic, that has a more unforgiving judgment regarding trans people, and there’s another that accompanies, welcomes, and facilitates a process of recognition. I think we need to educate people towards a greater sense of communion in diversity.”

Before hanging up the phone to return to her tasks, she adds: “I admire how she has had to fight since she was little. I don't think there has been a single valuable, insightful person who hasn't had a word that wasn't debated or criticized. They are people who are sometimes pioneers and are not understood in the time in which they live.”.

A little relief

A few months ago, while walking through downtown Buenos Aires, Mónica saw a woman lying on the ground next to a fruit and vegetable stand. “Her feet were a mess, and I wondered who would dare touch them,” Mónica shares at home, interrupted by Roco, her medium-sized white poodle. It was the impetus for her to study podiatry, a skill she now uses to help others. “Most people neglect their feet,” she says. She began volunteering at the Borda Hospital for inpatients. There she met Marcela, whose admission was an exception since the facility is primarily for men. “Trans women follow me,” she says, laughing. She also visited the Trans Memory Archive to provide free support to the veteran women who work there. “After so many years of being on the streets or highways, your feet are destroyed,” she says.

In one of the rooms of her apartment in Caballito, which the Church provided after much persistence, she decided to set up a podiatry practice, where she sees patients privately. She advertises her services on her Instagram profile ( @piealiviado ). She did this thanks to the help of “the girls,” as she calls the trans friends she has made over the years. When she shared her idea, they told her, “We’ll take care of everything.”

She spent last Christmas alone. She dedicated herself to praying for all the people who were spending that night alone. “'You're just another trans person,' they tell me. I always say that you have to truly understand the pain of others.”.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.