The Buenos Aires City Government must guarantee housing for the sole survivor of the triple lesbian murder

A court ruling orders the Buenos Aires City Government to guarantee decent housing for Sofía Castro Riglos, victim of the triple lesbicide in a family hotel in Barracas.

Share

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina . The courts have ordered the Buenos Aires City Government (GCBA) to guarantee Sofía Castro Riglos, the sole survivor of the triple lesbian murder in Barracas , access to decent housing as a matter of urgency. This is according to the ruling of the Court of First Instance for Administrative and Tax Matters No. 23.

Judge Francisco Javier Ferrer found the plaintiff's vulnerable situation proven and granted a two-day deadline for her inclusion in a housing program. In his ruling, he details the unequal conditions faced by LGBTQ+ people in accessing housing, lists local and international legislation, and cites authors Judith Butler and Monique Wittig.

“This ruling is very important because it holds the government, in this case the City Government, responsible for repairing the damage caused by the State’s absence and indifference towards the girls’ lives. It is a political act,” said Alejandra Rodríguez, a member of the transfeminist and anti-prison collective Yo no fui (I Wasn’t There), which supports Sofía.

The court decision was announced on December 11, in response to the injunction requested by Sofía Castro Riglos. It ordered the Buenos Aires city government to guarantee Sofía “access to decent housing, including her in a housing program that allows her to afford the current market value.”

The court also ruled that the City of Buenos Aires (GCBA) could comply with the order through a means other than housing subsidies, “provided it is not a shelter or hostel, and that it guarantees the satisfaction of the minimum content of the right (…) until the substantive issue is resolved.” The ruling—which is not yet final—stems from the case “CASTRO RIGLOS, SOFÍA AGAINST GCBA ON HOUSING INJUNCTION.”

Sofia, the only survivor

Sofía Castro Riglos is a 50-year-old woman. She grew up in a middle-class family, finished high school, and began college and university studies, but was never able to hold a formal job. In 2016, the house where she lived with her mother and son was auctioned off, leaving her homeless. She and her family lived in hotels and shelters, alternating periods of homelessness.

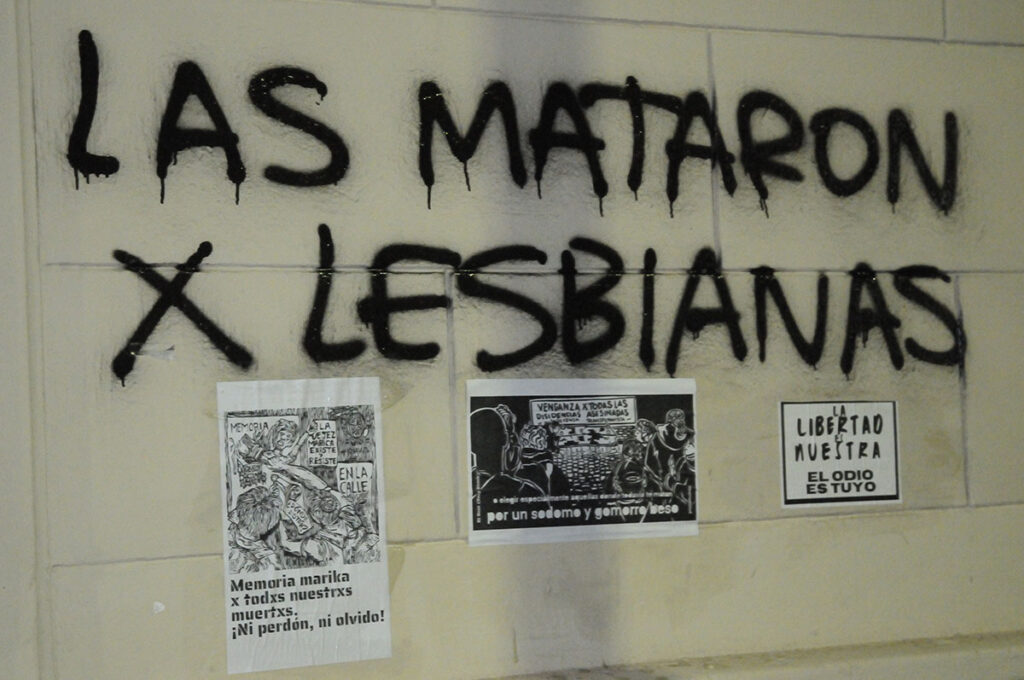

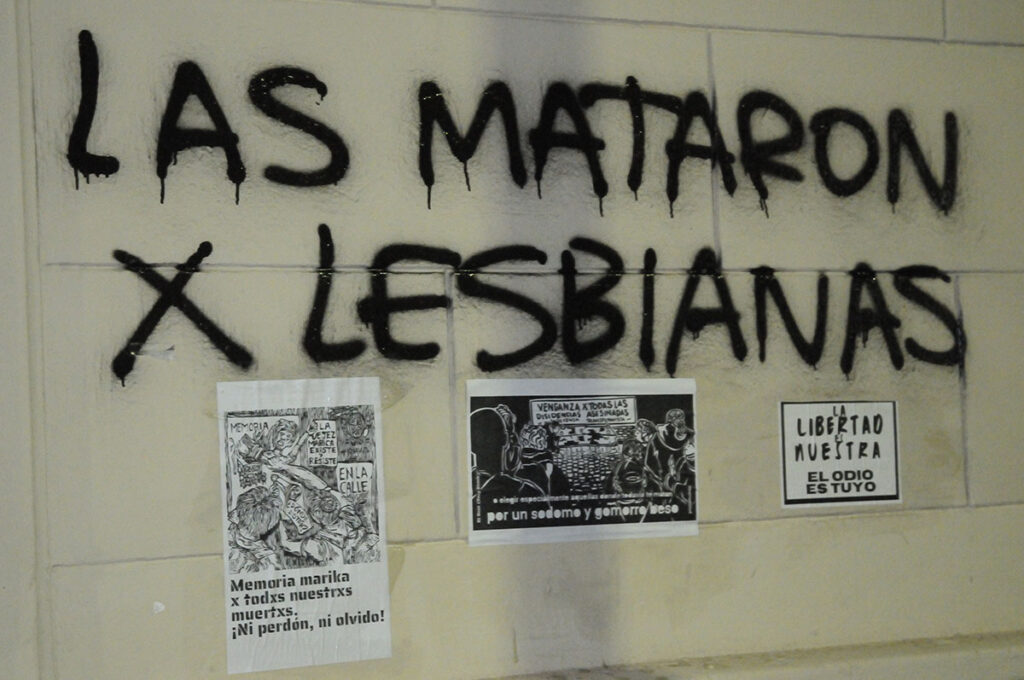

In recent years, she had been in a relationship with Andrea Amarante and lived with her and two friends, Pamela Cobbas and Roxana Mercedes Figueroa, in a room at the Hotel Canarias in the Barracas neighborhood of Buenos Aires. On the night of May 5th of this year, one of their neighbors, Justo Fernando Barrientos, threw a homemade explosive device into the room. Following the hate crime, Andrea, Pamela, and Roxana died, leaving Sofía as the sole survivor.

She spent a month hospitalized at the Burn Institute in the City and received visits from the team at the Laura Bonaparte National Hospital - which suffered an attempted closure last October - to treat the mental health problems she is experiencing due to what she went through.

She is accompanied by organizations such as the Self-Convened Lesbian Assembly for the Barracas Massacre , YoNoFui, and No tan distintes . The Assembly held a fundraiser that covered Sofía's expenses until October.

Given her vulnerable situation, Sofía had filed a legal action against the City Government. She requested a permanent housing solution that would guarantee her dignified, safe, and adequate living conditions.

Following the ruling, the Buenos Aires city government enrolled her in a program to provide housing assistance, enabling her to cover her household expenses. She lives in Casa Andrea, a collective and communal housing unit, with seven other women.

This ruling acknowledges that they were attacked for being lesbians.

Ferrer's ruling further highlights the problems Sofía faces. It acknowledges that the attack she suffered was due to her sexual orientation (being a lesbian), something the court handling the hate crime investigation failed to consider. This ruling also underscores the vulnerable social and housing situation in which Sofía found herself.

“We celebrate the court’s recognition of Sofía’s right to reparations, which includes guaranteeing her right to housing, ” reflected activist María Rachid, a member of FALGBT and head of the Institute Against Discrimination at the Ombudsman’s Office of the City of Buenos Aires. “In cases like these, whether femicides or hate crimes, the State must provide reparations to the victims and guarantee their human rights, just like everyone else, but even more so in cases where their physical integrity has been violated.”

Right to decent housing

Regarding the right to housing, the judge specifies that this right is detailed in both the National Constitution in Article 14 bis and the City Constitution in Article 31, which states that the district “progressively resolves the housing, infrastructure, and services deficit, giving priority to people in sectors of critical poverty and those with special needs and limited resources.” International legislation, such as the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (Article XI), also addresses this right.

Furthermore, the judge cites the local law on comprehensive protection and guarantee of the rights of people experiencing homelessness and those at risk of homelessness (Law No. 3706) of 2011, and Law 2957, which created the Framework Plan for Sexual Rights and Diversity Policies within the scope of the Undersecretariat of Human Rights of the Buenos Aires City Government. These are two city regulations that should have an impact on Sofía.

The ruling observes, from an intersectional perspective—though it doesn't explicitly state it as such—the structural violence experienced by the LGBTIQ+ community. That is, it recognizes that various factors contribute to conditions of inequality (poverty, sexual orientation, lack of housing).

“LGBT people can be victims of discrimination in accessing housing as a result of unfair treatment by public and private landlords. Among other problems, LGBT people and same-sex couples are denied rentals or evicted from public housing, or are harassed by neighbors and forced to leave their homes. Many adolescents and young adults who identify as LGBT are expelled from their homes due to parental disapproval and end up on the streets, making the number of homeless people in this group disproportionately high,” says UNHCR in the report “Discrimination and Violence Against Persons on the Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity” (2023), cited in the ruling.

It also details that “according to a recent study of 354 homeless support agencies in the United States, around 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBT people, with family rejection being the main reason why people belonging to this group lack a home.”

In parallel, the IACHR report “Violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Persons in the Americas” (2025)—also cited in the ruling—recognizes that homelessness increases the risk of violence for LGBT+ people. “According to research, homeless LGBTQ youth experience higher rates of physical and sexual assaults and a greater incidence of mental health problems and risky sexual behaviors than homeless heterosexual youth. For example, it has been reported that homeless lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are twice as likely to attempt suicide as their homeless heterosexual peers,” the research states.

Throughout his argument, Judge Ferrer explains what heteronormativity is—a set of legal, social, and cultural rules that compel people to act in accordance with dominant and prevailing heterosexual patterns—and why it affects Sofía's life. “Sexual stereotypes operate to demarcate acceptable forms of male and female sexuality, frequently privileging heterosexuality over homosexuality through the stigmatization of lesbian relationships and the prohibition of lesbians marrying or forming a family,” the ruling states, citing the IACHR.

The ruling cites the American philosopher Judith Butler and the French lesbian feminist philosopher and activist Monique Wittig. On the one hand, it points out that there is a way of differentiating lives, whereby some are “deserving of living, of protection, and of being mourned” and others are not. And this is because “power shapes the field in which subjects become possible or how they become impossible” ( Frames of War: Mourned Lives , by Butler, 2010).

On the other hand, she argues that the heterocisnormative system in which Sofia's situation is situated is built upon a social construction of difference, and from this construction a mechanism of oppression is built. “Masculine/feminine, male/female are categories that serve to disguise the fact that social differences always imply an economic, political, and ideological order. Every system of domination creates divisions on the material and economic planes,” Wittig emphasizes in *The Heterosexual Mind and Other Essays* (2006), cited in the ruling.

In a 35-page ruling, the judge concludes that Sofia's case, "far from portraying an individual situation, is part of a much broader system characterized by exclusion, stigmatization, and physical, cultural, and structural violence that impact her life, rendering it unintelligible."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

1 Comment