Militarization in Mexico: how it impacts the lives of women, LGBT+ people, and human rights defenders

What do we mean when we talk about militarization in Mexico? How does it affect the lives of women, LGBT people, and human rights defenders? Clues to understanding how the presence of the armed forces and the National Guard has changed social dynamics. Social perceptions, resistance, and proposals.

Share

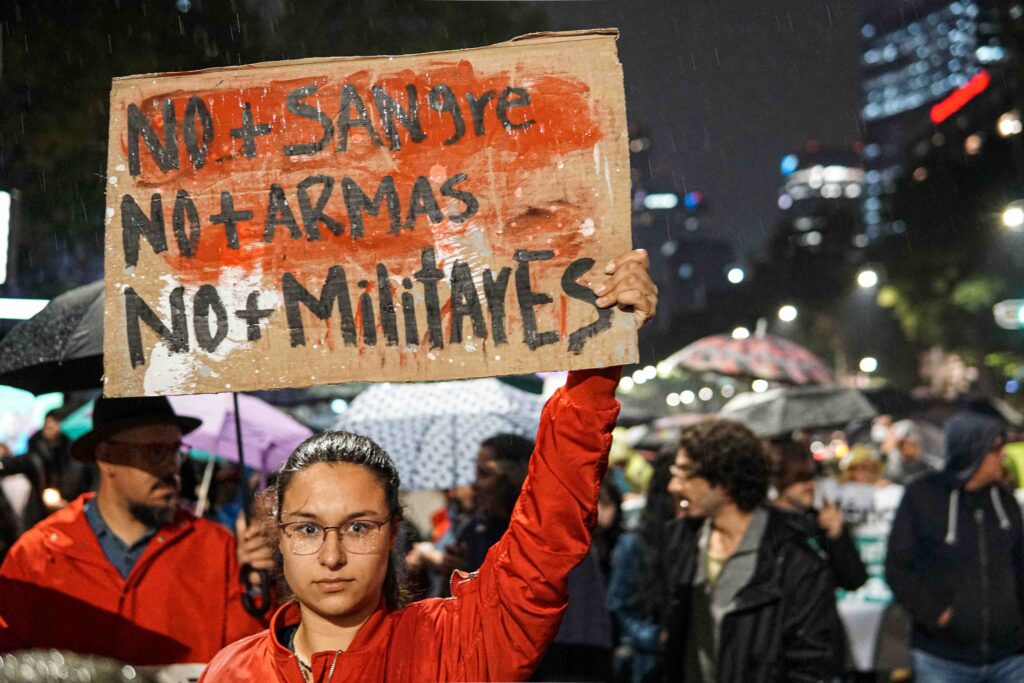

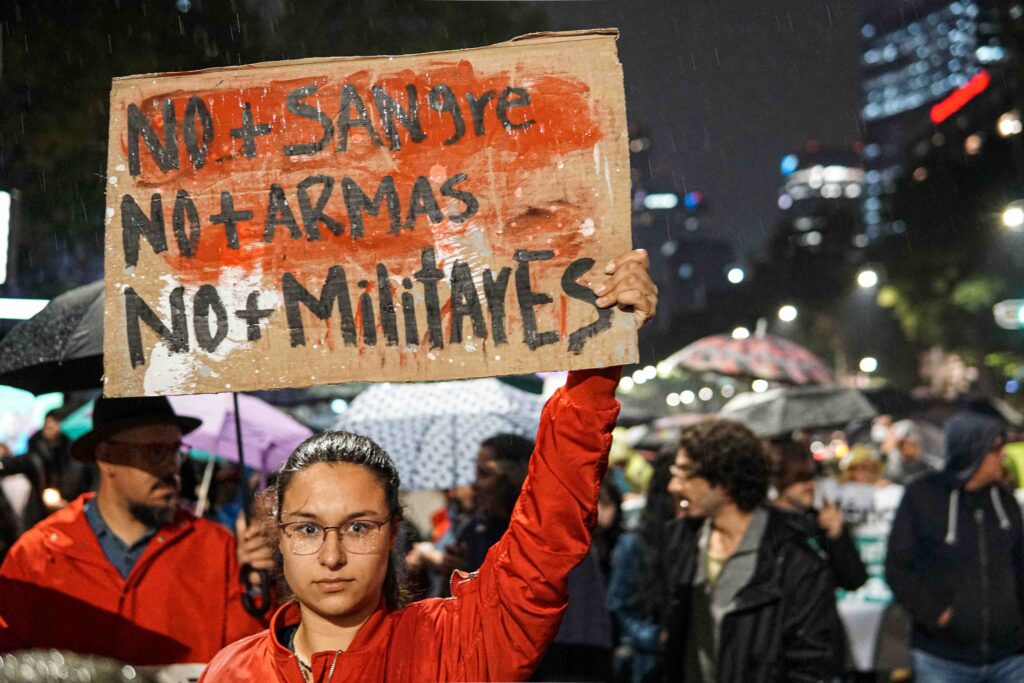

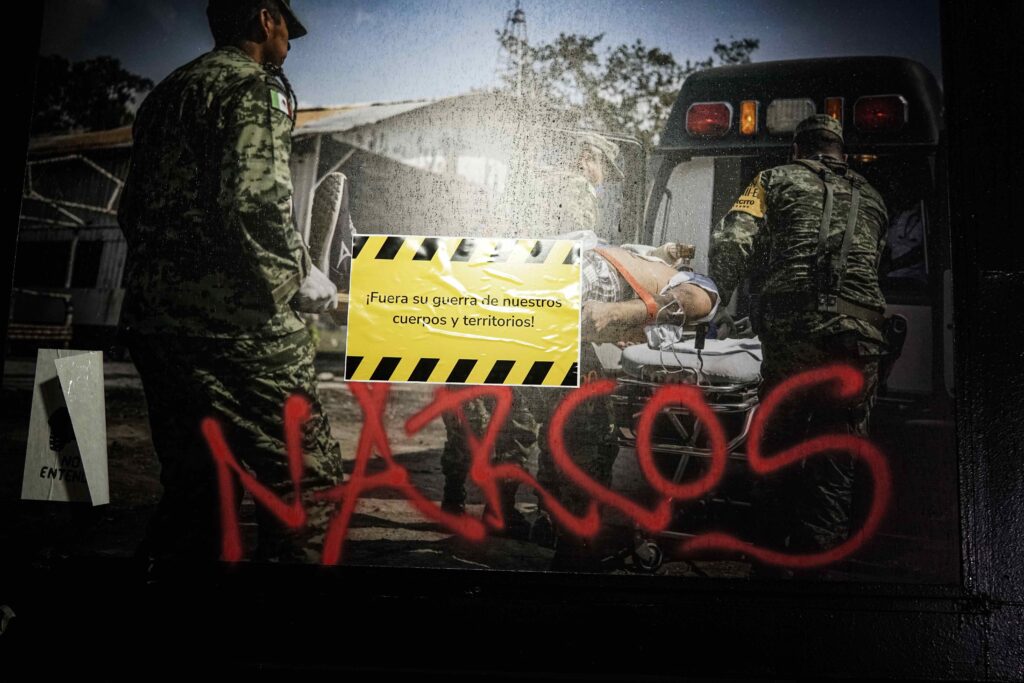

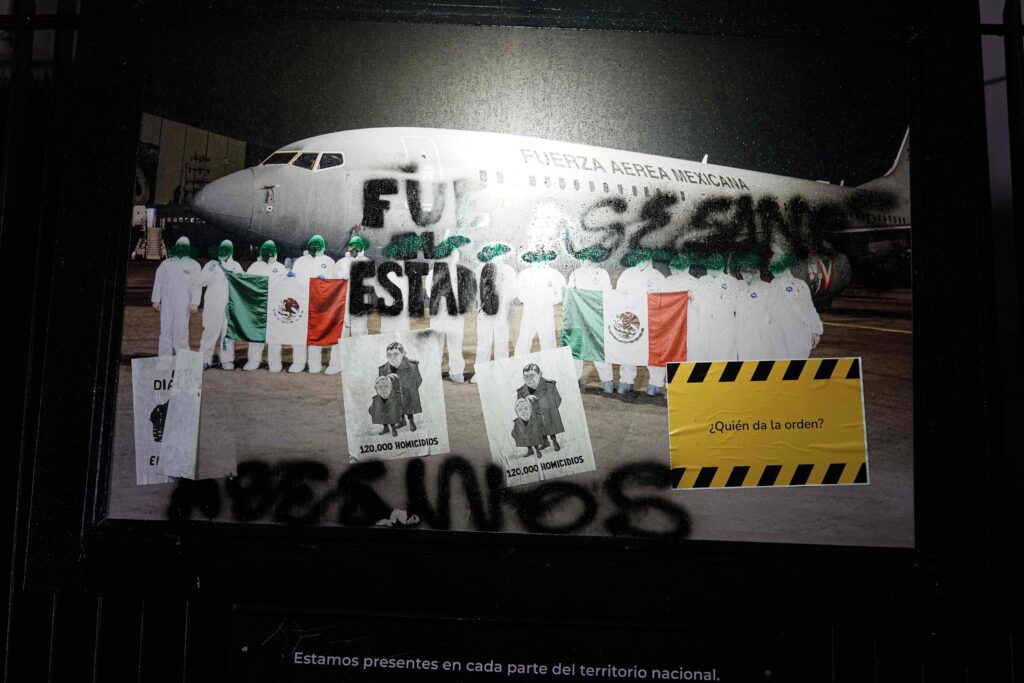

Militarization has been a constant theme and concern on Mexico's public agenda since 2007. That year, when the "war on drugs" was declared, a failed security strategy to combat organized crime began, encouraged by former President Felipe Calderón. The military left its barracks for public security tasks, but also for other duties such as border control, construction of megaprojects, and vaccine distribution.

Subsequent administrations did not change the security strategy. In her inaugural address, President Claudia Sheinbaum stated that “there is no militarization in this country.” However, organizations such as the UN and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) have expressed concern about the increasing role of the armed forces in public security tasks in Mexico and their connection to human rights violations .

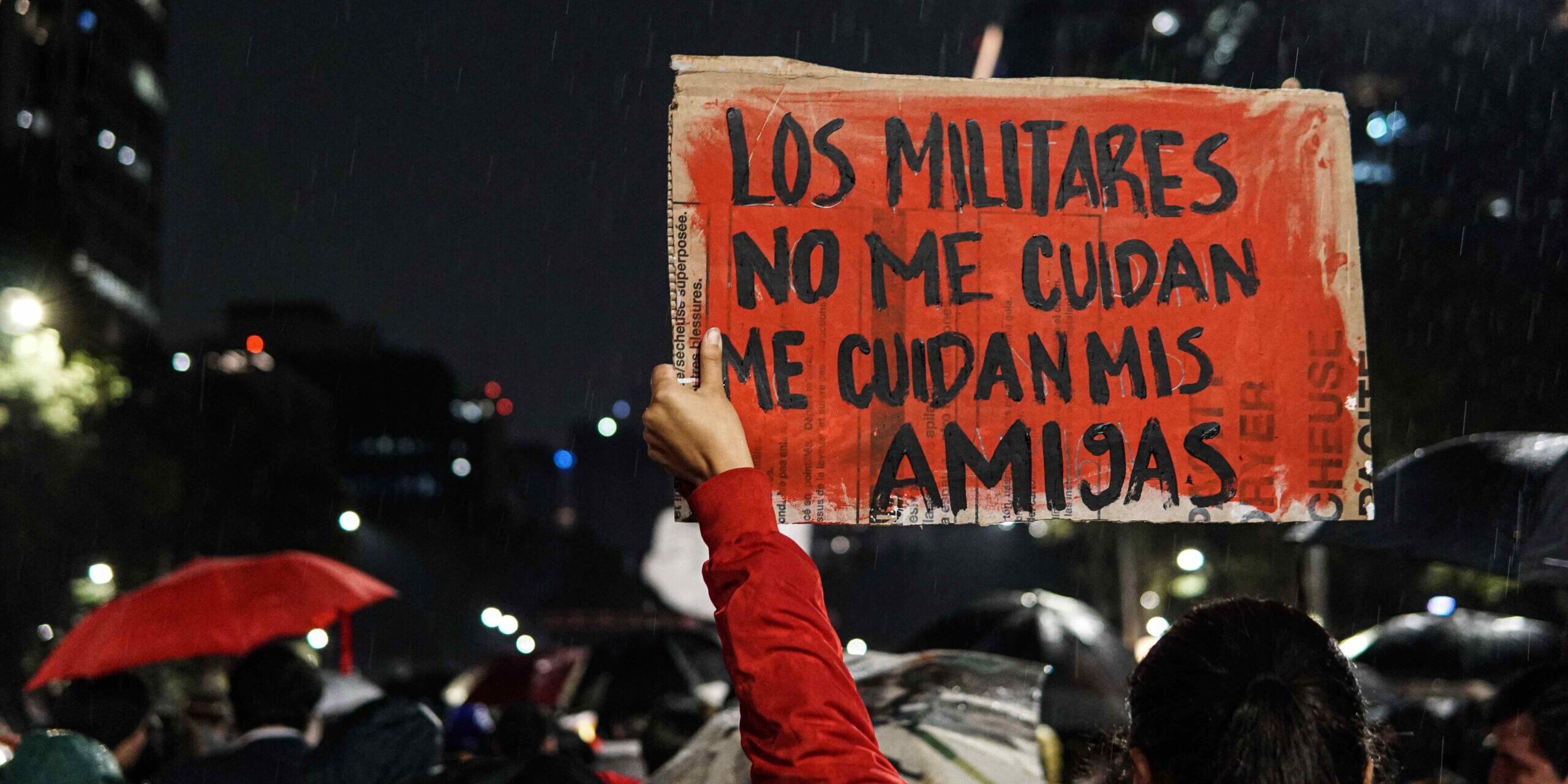

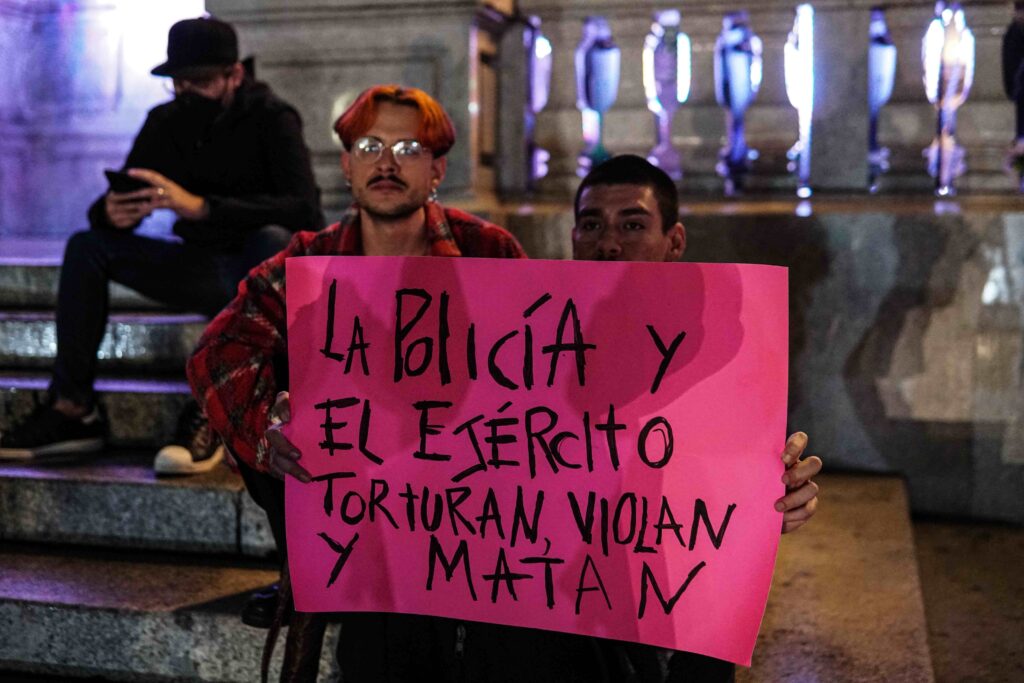

“The military presence in the streets has not brought peace.”

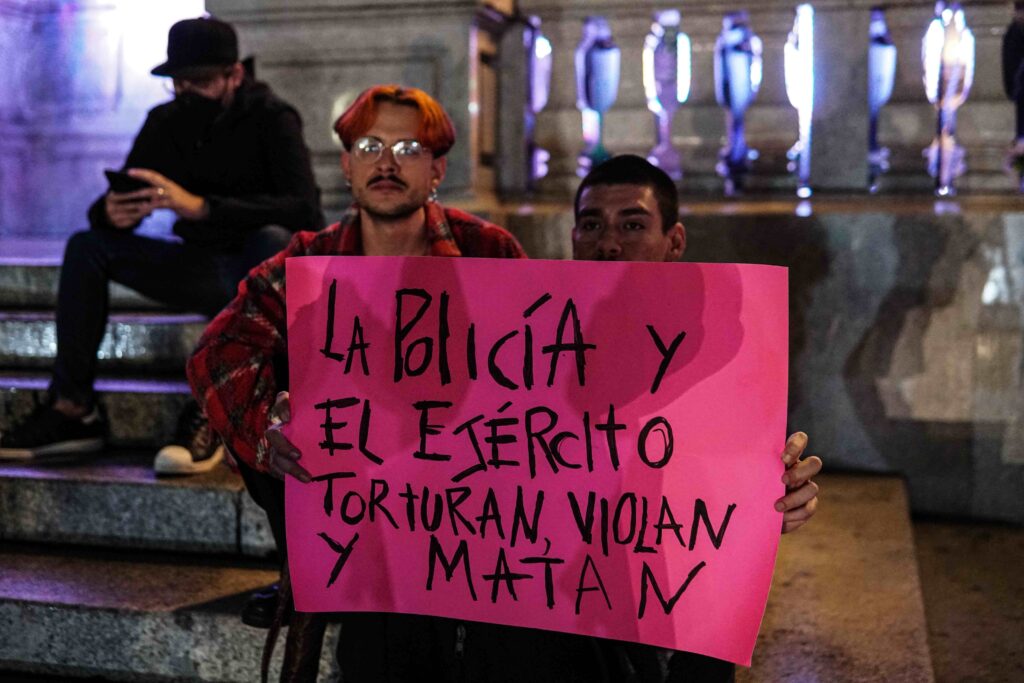

The presence of the military in daily life dates back to earlier times. But in the last three presidential terms—from 2007 to the present—the lethality of the armed forces in public security tasks has increased. Complaints to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) have also risen regarding human rights violations such as torture, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detentions, and extrajudicial killings perpetrated by the Army and the National Guard. This force was created by the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as part of its security strategy. The investigative journalism "Permission to Kill" details how the armed forces commit human rights violations with impunity.

“ Politicians who deny, and have denied, the existence of militarization have come from all political parties. This isn't a recent phenomenon. Today, we see soldiers walking the streets without any additional or different training beyond what they were trained for. This has impacted our way of life and our work. Historically, the military presence in the streets hasn't brought peace; on the contrary, it has increased human rights violations ,” says Ximena, a non-binary trans woman and defender of a territory in the Sierra Madre Occidental in Culiacán, Sinaloa, in an interview with X. This northern Mexican state has been one of the areas with the highest levels of widespread violence in the country due to the presence of the armed forces and drug cartels.

So, what are we talking about when we talk about militarization in Mexico? How does it affect the lives of women, LGBT people, and human rights defenders?

Militarization and social perception

Alicia Franco, Data Analysis Coordinator at Data Cívica (an organization dedicated to human rights through data analysis and construction), finds it difficult to believe that militarization doesn't exist in Mexico. She proposes discussing social perception , why the military presence is "justified," and how it's presented as " the only solution to public problems, with little evidence and little consideration of the alternatives ."

Alicia says, “ We live our lives with military logic in our language . There is an enemy, a good guy and a bad guy, and we have to attack. We have to conquer the territory of the bad guys . That's the logic behind the violence in many of our public problems—seeing it as the only solution.” She believes it's no coincidence that the military is viewed with affection . The military, she explains, invests in social perception to “maintain a sense of national identity. It's something inherited, learned, and linked to our idea of nation, of the revolution. And this is constantly being reinforced.”

For her, this positive perception of the military legitimizes the logic of war as the logic of solutions to the country's problems. Furthermore, the armed forces carry out public life tasks without accountability or providing information about their participation and decisions because it is an opaque institution . And that, from Data Cívica's perspective, puts democracy at risk.

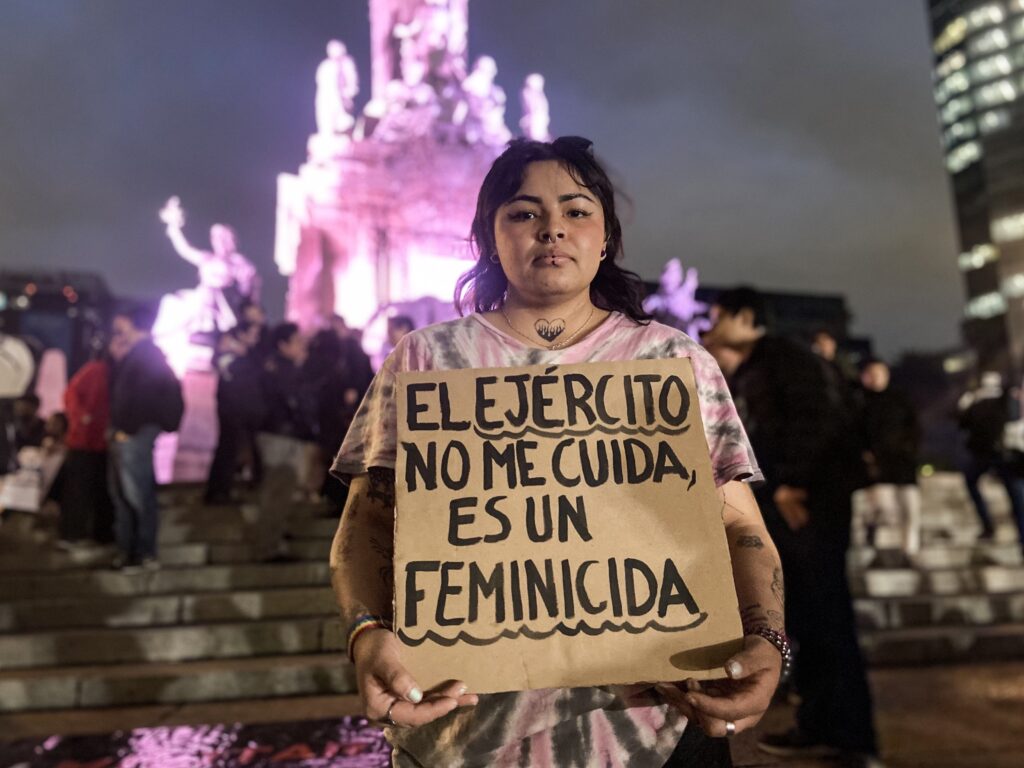

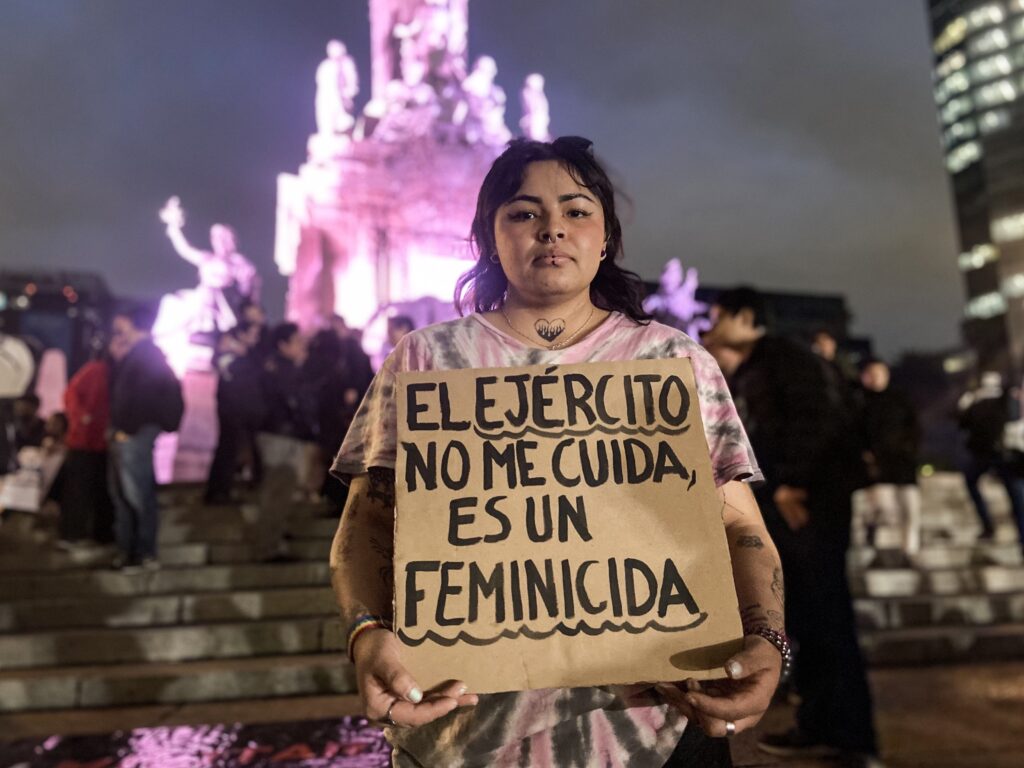

How militarization impacts women and LGBT people

The geographic presence of the armed forces has increased year after year since 2007, especially at the municipal level. This is the analysis of a study by the organization México Evalúa. How does this presence impact the lives of women and LGBT people?

“Since the surge in violence during the war on drugs, there has been an increase in armed violence and street violence, where women are disproportionately affected sexual violence, especially at the hands of the military, and this violence is perpetrated more frequently by the armed forces than by civilian forces (police),” Alicia explains.

Regarding the impact on LGBT people, given the opacity of military institutions, there is no hard data that would allow us to know and understand how it affects these populations.

Few recent statistical efforts consider LGBTQ+ populations. And in general, mortality data or reports of human rights violations, such as missing persons , are not disaggregated by gender identity and sexual orientation. When these information fields do exist , they are not always completed, either due to family decisions or institutional omissions on the forms.

However, a relevant finding analyzed by the organization Intersecta in their research on Gender Violence with Firearms in Mexico revealed that 5 out of 10 cases of violent deaths of trans women involved firearms as part of armed violence related to the war on drugs . In these contexts, security forces and criminal organizations are vying for territory, and trans women are being murdered not only due to prejudice-based violence.

“As a trans person, I honestly don’t see how to address the issue of militarization and advocate for change because of the fear it generates in me. I believe that as a trans community we cannot remain indifferent to what is happening; this is a first step, and it is necessary because there are trans people and people from diverse backgrounds who are experiencing this,” says Ximena con X, a trans woman and human rights defender, from Culiacán.

The fear Ximena speaks of is also experienced by other trans activists in other regions. At Presentes, we have been reporting on this perceived fear since 2023, especially in cases of transfemicide where the victims, most of whom were sex workers, were operating in contexts controlled and threatened by drug traffickers and the police, making it impossible to seek justice.

Peace has to come from the community

“Peace has to come from the community ,” Wilma points out in an interview with Presentes. “ I understand that some people believe it’s built through militarization, but that’s not the case,” says this defender of the Mayan territory of Noj Kaaj Santa Cruz, now known as Felipe Carrillo Puerto in Quintana Roo. Wilma is a member of the U Kúuchil K Ch'i'ibalo'on Community Center and has spent years denouncing racism and sexism in the militarization of the country.

“Now, with the construction of roads and megaprojects, the military is establishing a presence in the area. That's when we saw the escalation; the National Guard, the Army (Secretariat of National Defense), and the Navy are taking control. That's when we started hearing that Carrillo Puerto is a military zone,” Wilma adds.

Regarding how they understand security in this territory and how to take care of themselves, Wilma says that they are forging security through dialogue with anti-militarist networks, creating and maintaining "dialogue among ourselves, and having niches of life."

“It seems like a huge monster is coming. And it is. But we can’t think that nothing can be done. We continue working with other groups to build and think, even amidst the hostility. Comrades in other states have even taken up arms to defend themselves because they had no other choice, because they’ve been attacked with drones and weapons to kill. We wouldn’t want that to happen,” Wilma concludes.

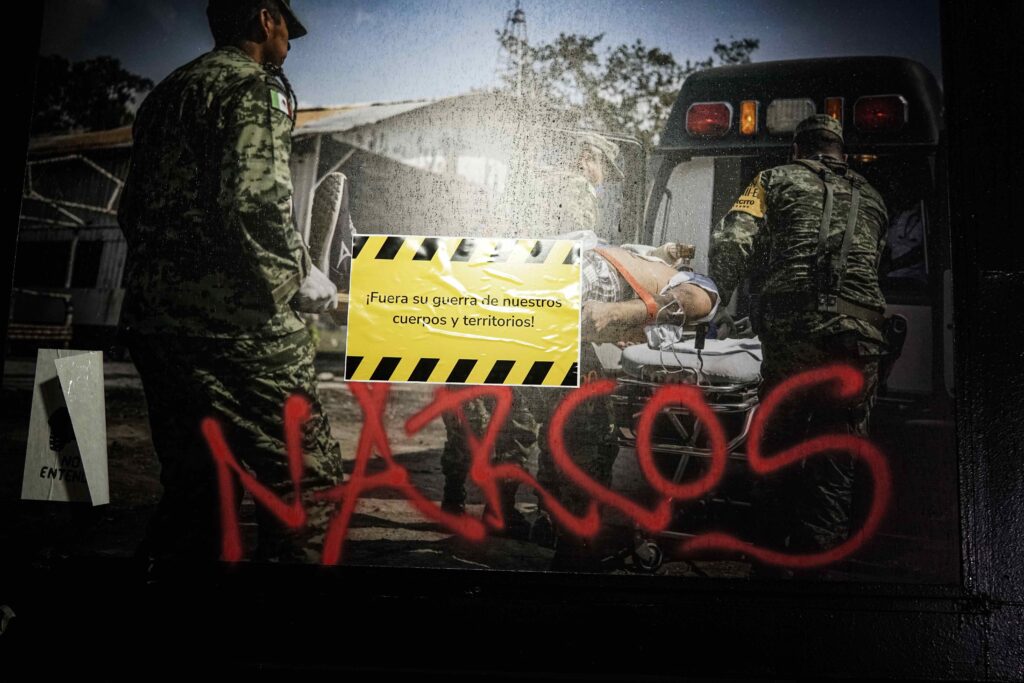

The horrific scene Wilma describes is happening and has happened in other parts of the country. In 2015, members of a drug cartel shot down a Mexican army helicopter in Michoacán. Another tactic is the use of drones. The media outlet Connectas documented this and how it has led to the forced displacement of communities in Guerrero . According to official data , more than 600 drone attacks have been recorded in the last four years. Furthermore, this Wired report indicates that these attacks “have resulted in dozens of deaths, injuries, and the displacement of entire communities.”

The use of force and technology has also been employed by the military, resulting in killings, injuries, and cities paralyzed by fear . In 2017 in Tepic, the army flew over a town and fired 500 rounds per second from a .50 caliber machine gun from a helicopter. This was done to take down a cartel leader, and it led to serious human rights violations due to the excessive use of force, including raids on homes without warrants, arrests, interrogations, and intimidation by police and military personnel.

More disappearances, murders and femicides

In the municipality of Carrillo Puerto, Wilma says, the murders and disappearances of women and young people have increased in the last six years.

In 2023, the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System registered 848 femicide victims and 2,591 intentional homicides. In total, 3,439 women were victims of femicide and intentional homicide. Of these, only 25% are being investigated as femicides.

According to the Intersecta investigation "The Two Wars ," militarization and clashes with organized crime groups are contributing factors to the increase in femicides in the country. In this context of widespread violence, firearms are the most commonly used weapon in these crimes.

Furthermore, according to data from the Network for Children's Rights in Mexico (REDIM), intentional homicides and femicides against children and young people have increased with each presidential term. Firearms are also the most frequently used weapon in these crimes.

During Andrés Manuel López Obrador's six-year term (2018-2024), an average of eight girls and young women were victims of femicide and 14 victims of manslaughter per month; in the case of boys and young men, the average per month was 73 victims. Firearms were used in 61.2% of femicides and manslaughter cases against girls and young women. For boys and young men, the figure was 73.7%. These figures represent an increase compared to the previous six-year term (2012-2018).

“Militarizing to pacify doesn’t work”

Wilma also believes that militarization didn't begin with former President Felipe Calderón's declaration of war on drugs. But it has intensified with the federal government's megaprojects, such as the Maya Train and the Puerta al Mar (Gateway to the Sea). The military controls a sacbé, a road built by the ancient Maya, which now allows businesses to enter and profit from the reserve.

Another high-profile instance of militarization has been mislabeled by the press as the “Culiacanazo.” It occurred on October 17, 2019 , when organized crime seized control of the city of Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa, a state in northern Mexico. Ximena, the land defender, is from Sinaloa.

The control exerted by organized crime prompted the withdrawal of the armed forces in response to the failed attempt to capture the son of drug lord Chapo Guzmán.

The presence of the military and drug cartels paralyzed the Sinaloa capital. Ordinary people were caught in the crossfire, resulting in more victims of human rights violations. But this is nothing new, Ximena points out. These are symptoms of an all-out war, marked by constant roadblocks, arbitrary arrests, disappearances, and executions in this and other parts of the country where municipal and state police are absent .

“It’s not just the noticeable presence of members of the Armed Forces, it’s the Mexican State’s permissiveness and the impunity that allows it to happen. We’re talking about the occupation of rural villages in the mountains by soldiers, how they beat us, how women were raped, how people were tortured with the complicity of the Mexican State. We’re talking about the Army’s presence in locating and destroying marijuana plantations, but also in dispensing justice, in grabbing someone, making them disappear, or beating them to a pulp,” explains Ximena con X, a land defender.

The military presence reshapes the daily lives of citizens, their schedules and activities.

“At what point did the armed forces and national guard become part of the landscape? At what point are there tanks in the city streets? At what point did their presence change social dynamics? Nightlife after seven is unknown. But we do something as a community because life also has to find a place. Organizing is dangerous in this context. But talking about it, sharing what we have experienced, and stating clearly that militarizing to pacify doesn't work , is a first step,” Ximena concludes.

On September 9th of this year, Culiacán experienced another peak in violence. Revista Espejo, a local news outlet, reported that the number of forced disappearances has surpassed 500, mostly of teenagers and young adults, in addition to more than 420 homicides. Furthermore, the military is abusing its power; a video shows them shouting “kill him, kill him” at a man they had shot and arbitrarily detained in the city.

In the first month of President Claudia Sheinbaum's administration, several incidents were recorded in which the armed forces participated in extrajudicial killings, resulting in at least 30 victims . In one incident, six migrants including an 8-year-old girl were killed by the army and the National Guard .

Following these initial incidents, Sheinbaum stated in a press conference that "when the armed forces are attacked within the framework of the law, they have the right to respond in self-defense." She added that they will continue their security policy "with investigations and by addressing the root causes."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.