Lesbian Memory: With my memory I lit the fire, the biography of Mónica Briones Puccio

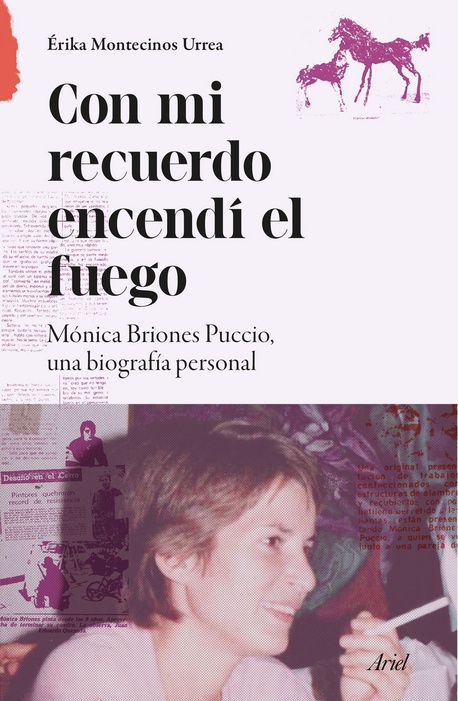

A preview of *With My Memory I Lit the Fire*, the biography of artist Mónica Briones Puccio, murdered on July 9, 1984, in Santiago. The book commemorates Lesbian Visibility Day in Chile in her honor. It weaves together memory, art, lesbian feminism, testimonies, case files, and a play of mirrors through which the author, activist Erika Montecinos, journeyed.

Share

In 2006, journalist, writer, and activist Erika Montecinos (Santiago, Chile, 1972) began investigating the story of Mónica Briones Puccio, an emblematic lesbian artist. Her *With My Memory I Lit the Fire *, recently published by Planeta , reconstructs much more than just the life of Mónica, who was beaten to death on July 9, 1984, in the heart of Santiago during the dictatorship, while waiting for a bus with a friend after celebrating her 34th birthday. The crime was perpetrated under circumstances about which very little is known and remains unpunished. It was not just another violent death. It is recorded as the first documented case of lesbicide in Chile, , July 9 is commemorated every year Lesbian Visibility Day .

Lesbian visibility from Chile to the world

Erika, the book's author, is also a crucial activist for lesbian visibility . In 2002, at the height of the internet boom, she founded the digital magazine Rompiendo el Silencio (Breaking the Silence). It takes its name from a radio program she hosted in 1998. The publication later transitioned to print, crossed Chile's borders, and reached several Latin American countries (it ceased publication in 2010). In this publication, Erika published the first part of her research on the painter and sculptor Mónica Briones Puccio. In 2014, Erika relaunched the magazine as an organization, working alongside other activists to focus on political advocacy and to bring the needs and demands of lesbians and bisexuals to the forefront of the public agenda. In Chile, the right to legal parentage—enclosed in the Equal Marriage Law—owes much to the lesbian feminist struggle and the work of Rompiendo el Silencio.

Erika has an international career as a journalist, communicator, and activist. In 2020, Equality Now selected her as one of the six LGBTQIA+ activists in the world to know. She was a columnist for The Washington Post, completed a creative writing diploma at Diego Portales University, and has participated in international LGBTQIA+ leadership conferences such as Rainbow Leaders in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2014; Cape Town, South Africa, in 2015; and the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) World Conference in Los Angeles, USA, in 2022.

Today she works in the Sub-Directorate of Gender Equality, Sexual Diversity and Inclusion of the Municipality of Santiago, as a member of Chile's first feminist government. “Breaking the Silence marked a before and after in my life. It was the path I took not only thinking about a personal milestone, but also about helping many lives,” she told Presentes in an interview .

Biography and labyrinth of mirrors

She was finishing university when she heard about the case that deeply affected her, sparking surprise, fear, questions, and curiosity. She embarked on a laborious journey: tracing the path of a life story and a violent death, visiting the places Mónica frequented and lived, tracking down files, and listening to friends and acquaintances. She approached Mónica's work from new angles and with new questions. She recounted an era and a way of defying it. She learned the details of Mónica's life as an artist who also lived her sexuality openly and freely amidst the military dictatorship that ruled Chile in the 70s and 80s.

The investigation she undertook also ended up intertwining with the author's life, in a kind of hall of mirrors. "With My Memory I Lighted the Fire," published by Planeta, has just been presented at the Museum of Memory in Chile. You can read an excerpt here.

With my memory I lit the fire

Living is a kind of madness that death commits.

A breath of life

Clarice Lispector

To the first ones, to the many invisible stories.

*All subtitles in this book are excerpts from the songs "No me arrepiento de nada" and "La vie en rose" by Edith Piaf, in their Spanish versions..

Part One

Life [almost] in pink

1

We were sitting in a circle in a large room on the top floor of a downtown building. It was the last month of the year, in the late nineties. We were sharing stories of our lives with a lesbian women's organization. In the middle of the conversation, one of them mentioned a crime against a woman, saying it would be good for the new members to know what happened. She was a sculptor, a lesbian sculptor who was thirty-four years old when she was murdered in 1984. Her name was Mónica Briones, and she had been beaten to death in the street. I opened my eyes, surprised and uneasy, as if I were just now understanding that my safe haven was fragile, that this terrible possibility existed. The impression the story made on me made it impossible to forget her name or that small part of the story, which seemed to be the only piece of information available.

Many things were said about her. That she possessed a singular beauty, that she was a unique artist, but without opportunities, with erratic passions, defiant of the established order, that she openly embraced her sexuality, that she was part of the underground during the dictatorship, and that the writer Pedro Lemebel had dedicated a chronicle to her. I understood that she wasn't just any woman who had been murdered, not just another militant on the long list of victims of the regime we had emerged from barely a decade before; she was someone with a mystique, so to speak, someone who lived each day intensely, as if she knew her time was short. Everything those activists said at that meeting, where I was a university student, fueled my curiosity to investigate the reasons for her death. In those years, I was graduating with a degree in Journalism and beginning a new phase in my life where the job market seemed broad and everything looked promising, fresh, almost rosy.

Over time, I kept hearing about her, and each time it came up, I insisted on the possibility that she might have surviving family members, friends, or lovers who could bear witness to her life. It was always the same answer: the family didn't want to investigate; they covered everything up. I was told it was so traumatic for those who knew her that it was understandable they didn't want to know more. I couldn't imagine what it must have meant for her loved ones to have a friend murdered. Remaining silent in the face of horror is a way of protecting ourselves. That's why, when I remembered it, trying to find some way to delve deeper into those evasive answers, or when events in my fledgling activism led me back to the same story time and again, the question remained, like a flickering light, sometimes annoying, sometimes uncomfortable.

Mónica lived her lesbianism openly, without hesitation or shame, and that came at a price in Chile in the mid-eighties. It's difficult to discern the reasons for what happened to her: that she had gone out to celebrate at a bar somewhere along the Alameda, had a drink, and upon leaving, someone confronted her and beat her to death. All of this shrouded in contradictions. When we went to university parties, almost fifteen years after her murder, we felt no fear; we were no longer under a dictatorship, and we could, supposedly, wander about without fear of being arrested.

I remember drinking a can of beer at a soda fountain across from a plaza, a young woman without too many worries, and sitting there with that bittersweet taste in my mouth, thinking about everything the activists had told me: the danger we face in any space, on the street, even among family members, how fragile our lives become when we come out. I imagined myself in a somewhat cheerful, perhaps even seductive, environment, where glances are exchanged, feeling beautiful, sensual, and then suddenly going out into the street, getting into an argument with a stranger, and being beaten unconscious. Other theories circulated, as if the oral version allowed for adding or subtracting elements in the vast human imagination. One was that I had been run over and left in the street. Another was that I started looking at a man's girlfriend, and that man, jealous, had "overreacted." Local television recreated the scene based on this hypothesis in a report on the program Informe Especial about “Lesbians in Chile” in 1998. Deep down, nobody knew anything. What had really happened to Mónica?

Apparently, in 1984, there was nothing that connected her and me—no relatives, no friends. At the time of her murder, I was around twelve years old, and she was twenty years older. At twelve, I was beginning to question my own identity. Hers was truncated by living that very same identity within a repressive context. At twelve, I was slowly saying goodbye to childhood; she, to life. From the very moment I heard her name in that organization, I decided I would investigate her life. And it wouldn't be just any investigation, not one that simply gathers documents, recordings, photographs, evidence, but one that would evolve toward a discovery—I didn't yet know what it was, but something much deeper than her end.

I wasn't sure, though, that I was capable of undertaking a task of that magnitude. As the years went by, and through my activism, I met people who had known her, and I was certain they knew a great deal about Mónica. I insisted that there must have been some prior investigation, some date, something to hold onto to unravel the mystery. I wasn't satisfied with those laconic and categorical answers: "the family covered everything up," "they didn't want to know." I wanted to know about Mónica, and not having known her when she was alive wasn't an impediment to wanting to delve deeper than her violent end. Nor did I know how far I could go if the entire narrative surrounding her, her whole world, was based on what others told me; ultimately, on secondary sources.

In July 2006, I sat down at my computer and felt the moment had arrived. Those same people who claimed to have known her might be able to guide me with some background information on where to turn. I began to locate them, made a list of their names, and took every opportunity to tell them about my project. They looked at me with suspicion, I must admit. Because up until that moment, they had doubts about my true commitment: either I was a human rights activist for lesbian women, or I was driven by journalistic morbidity.

I wasn't the one who had that answer.

** *

6:40 am, Monday, July 9, 1984

Dawn breaks over the city. A trail of clouds is visible across much of it. Finally, the rainstorm begins to subside for a while; it has been eleven days of uninterrupted rainfall, one of the deadliest storms on record, surpassed only by the one in 1982. "The storm hit Chile!" headlined the newspapers that morning. Photographs from that day show flooded streets, two people standing in the middle of a river as buses speed by, drenching them. There are rocks rolling downhill on Los Libertadores and numerous abandoned vehicles at the international border crossing, and mud in the neighborhoods. "350 millimeters of rain so far this year, exceeding the average," they commented on the radio.

At the First Police Station, the telephone rings—another call, perhaps a false alarm, a prankster, another drunk hit by a hit-and-run driver. The order from superiors is to inform the newspapers that it has been a deadly weekend for traffic accidents. Santiago experienced a wave of these incidents. The number of traffic victims has risen to thirteen, according to the official information provided to the press by the Traffic Accident Investigation Unit (CIAT). The officer picks up the receiver, his mind racing as he obeys his lieutenant's order, repeating what they have been accustomed to doing generation after generation: "[...] Irene Morales Street and Merced Street," the officer jots down on a lined sheet of paper. "Do you have any further information about the deceased?" "Yes, I heard that. The body is lying in the middle of the street." "Okay, a unit will be dispatched there."

6:55 am

Almost instinctively, the corporal radioed CIAT's Team Eight to report another hit-and-run. Lieutenant Miguel Yevener was in charge of the unit that morning, but he assigned Second Lieutenant Antonio Campos Cortesi to the intersection of Irene Morales and Merced streets. For Campos Cortesi, it was a routine call, just another one on his third shift; he would have many more in his life, like confronting university students and becoming involved in a case of unlawful coercion against one of them. But that morning, he boarded the patrol car with Corporal Exequiel Hernández and, along with the unit's photographer, they headed to their assigned location.

7:15 am

Campos Cortesi gets out of the patrol car; it's cold. After the rains, a polar cold is forecast. The thick coat issued by the institution weighs him down; he adjusts his cap, and the corporal accompanying him does the same. He's taller than him, broad-shouldered, a big man. He notices colorful minibuses lined up on Merced Street, their headlights twinkling through the dew. A few raindrops are still falling, but they're spaced out. The old vehicles pass slowly by, as if afraid of hitting something lying there in the middle of the wet pavement, its petrichor scent permeating everything. They order the entire perimeter to be secured while they examine the bundle discarded a little further from where they've parked; it's a body, the body of a woman, face down. Together with Corporal Hernández, they begin the inspection. Campos Cortesi asks the second corporal to cover the body with a beige the woman was wearing. The officer notices that there are several bloodstains on its lapels. They don't wear surgical gloves, they handle the clothing carelessly. They place a sign next to the body that says "ciat". The flash illuminates the entire street; the people getting off the buses at that hour are frozen in the snapshot, some staring at the bundle with wide eyes, paralyzed. There are others nearby, saying they were in the Jaque Mate bar when they heard screams and ran to see, but there was no one else on that corner, only that lifeless body in the street.

The police agree that it must be a hit-and-run accident; it's common on stormy days, there's no other explanation. They note it down in their notebooks.

7:30 am

Ambulance number 66 from the Central Post Office arrives quickly. There's not much to do, they say; the order is to take the body directly to the morgue. Corporal Hernández rummages through the clothes of the deceased woman, who lies face down on the pavement. He will later note that the pool of blood surrounding the body is running down the pavement due to the intensity of the rain, which falls like a red river illuminated by the dawn. He looks for any identification and manages to find a piece of paper in the purse the deceased apparently carried. The paper is a photocopy of an identity card and says "María Briones…" but he can't make out the second surname or the card number; it's blurry. "Purgio," he writes in illegible handwriting, "María Briones Purgio," "Chilean, no identification," and on the next line he writes "body in a state of indecency." One of the patrons of Jaque Mate, who is watching the

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.