Interview with Yobaín Vázquez Bailón: Does LGBT literature exist?

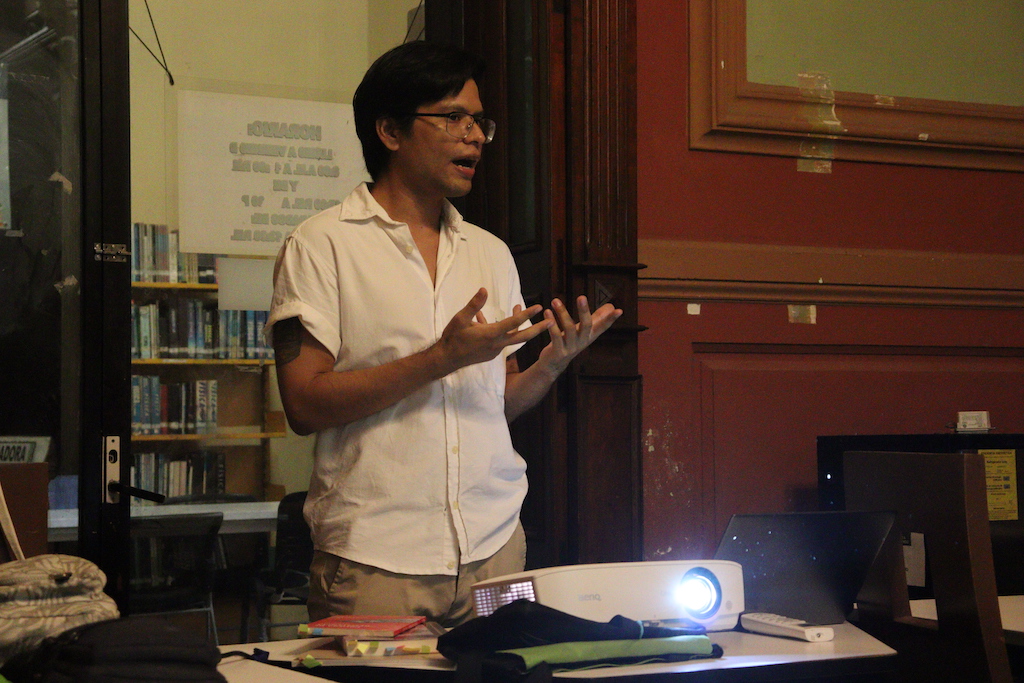

Interview with writer Yobaín Vázquez Bailón, winner of the José Revueltas National Young Novel Prize (Mexico). LGBT+ literature, uncomfortable categories, characters, and meanings of fiction.

Share

MEXICO. Does “LGBT+ literature” exist? Yobaín Vázquez Bailón, winner of the 2023 José Revueltas National Young Novel Prize in Mexico for his work * La Travestiada* , a historical novel about the Dance of the 41 , affirms that it does. He has been writing short stories with gay, lesbian, and trans protagonists since 2020. That same year, he received an honorable mention in the Beatriz Espejo National Short Story Prize, and during the awards ceremony, he held up a sign that read, “The state that is awarding me this prize is homophobic, misogynistic, and repressive,” because a few days earlier, the authorities of Yucatán, Mexico, where he is from, had repressed a demonstration and voted against same-sex marriage. On that occasion, Vázquez won with his work * Cuidados paliativos *, which features a trans woman as its protagonist.

An awkward category

“Not many are comfortable with this category because writers interested in these topics (of the LGBT population) tended to be labeled as “niche writers,” who only wrote for certain readers and about sexual or gender issues. But I think that in recent years it has been shown that LGBT literature is something broader. That it speaks of a human experience that is as valuable as any other,” he says. Yobaín is a writer, market vendor, and anthropologist. He has just published his first book of short stories, Cristo es otra forma de hacer drag (Christ is Another Way of Doing Drag ).

From their perspective, labeling this type of literature as LGBT is a way of making visible a series of experiences of lesbian, gay, trans, non-binary, bisexual people that, with some exceptions, had not been very well represented in literature .

Yobaín recently conducted an LGBT storytelling workshop in Mérida, Yucatán, in southern Mexico. This workshop was specifically designed because these stories are not easy to find and are mostly found within the LGBT diaspora. “You’ll never find these stories in school textbooks, and if they are studied, it would be at universities. From what I’ve read in LGBT literature, I began to see certain connections between the works, even stereotypes and clichés, which I felt were important to share for critical analysis.”

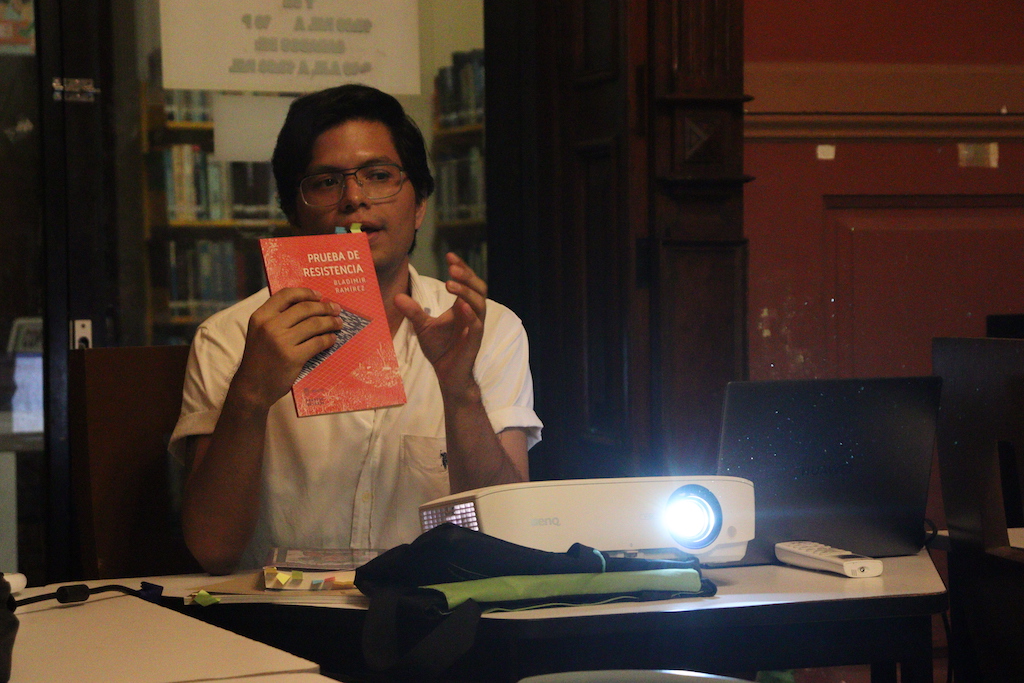

In the workshop, the participants (students, historians, reading enthusiasts, teachers, restorers, and theater professionals) read works by Bladimir Ramírez, Elena Madrigal, Virginia Hernández Reta, Aura Saina, Criseida Santos Guevara, Camila Sosa Villada , Silvia L. Cuesy, Gilda Salinas, Brissia Yeber, Joaquín Hurtado, Luis González Alba, Sergio Loo, and others. After each reading, they discussed it and asked questions such as: How has the LGBT population been represented? What stories have been told? What stories remain to be told?

They discussed the clichés and narratives that have persisted throughout the history of LGBT literature (even before it was recognized as a category), particularly the tragic narrative. Regarding this, Vázquez opined: “It’s a reflection of what existed (and continues to exist today), but if we only focus on the story of the gay man who suffers, the lesbian who dies, the trans woman who is violated, the story is incomplete. It’s not that literature’s mission is to show us a happy world, but rather glimpses of different perspectives, not just tragedy .”

One example is the case of the Dance of the 41, since the story of the clandestine parties only became known after the raid and the arrests. But before that, there were 40 years of parties that went unreported. “That makes us feel as if we’ve always lived in the shadows,” says the writer.

Historian Sergio Ceballos, who participated in the workshop, shared that much of what has been documented about the LGBT population stems from criminalization, from sensationalist crime reports and police records. He shared that while it's possible that LGBTQ+ individuals have been accepted into their communities for various reasons, this hasn't been widely publicized because it was something that wasn't discussed.

Perhaps one of the most significant changes in literature featuring LGBTQ+ characters and stories is who writes them. Yobaín Vázquez says that initially, it was generally cisgender heterosexual writers who created LGBTQ+ characters from a cisgender heterosexual perspective. “However much they wanted to embody the vision of an LGBTQ+ character, if you're a discerning reader, you realize that their heterosexuality permeates the narrative. These days, there are more LGBTQ+ writers telling stories with their own voices. Right here in Yucatán, there's the novel * La casita de muñecas* by Naná de la Fontaine, a non-binary person. I think it's the first novel with a non-binary perspective in Mexico.”

"The future of literature is LGBT literature"

The contributions of LGBT writers about their experiences have also transformed the way diverse characters are portrayed in works that may not have LGBT experiences as their main focus. Or consider cases like the novel by Xochitl Lagunes, a cisgender writer who wrote about an unequal relationship between a young man and an older man, without romanticizing it and by exploring the complexities of experiences that she herself may not have.

The interviewee confesses that this happened to him when he began planning the short story workshop, as he realized he hadn't read any lesbian fiction. He found the anthology * Until It Begins to Shine* by Artemisa Téllez. When he shared it with workshop participants, he realized he knew nothing about the lesbian perspective. He was surprised by things that are very obvious to most lesbians: “It was like discovering a completely different world. I found that very valuable, establishing those connections and dialogues with other people who, although we recognize ourselves as part of the same community, have no idea what others go through in their daily lives.”

When asked about the future of LGBT+ literature, the writer answers without hesitation: “The future of literature is LGBT literature, that’s how I put it. It’s already happening: a novel by Camila Sosa Villada ( Las malas , winner of the 2020 Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Literature Prize) was incredibly refreshing when it was published precisely because it offers a different perspective from the many stories about (heterosexual) romances that have already been read. And in Mexico, the possibility is opening up for these perspectives to be more widely read.”

Another example is Kim de l'Horizon, a non-binary writer from Switzerland who won the 2022 German Book Prize for their work *Blutbuch* ( ). According to Vázquez, in * Blood Book* , they "dynamite what we know as a novel," mixing time periods and structures, employing fragmented narratives, and lacking a traditional storyline. "It's no coincidence that LGBT people are venturing down uncharted paths in literature and sharing perspectives that were previously unseen."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.