Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) with Mapuche identity: between pleasure and territory

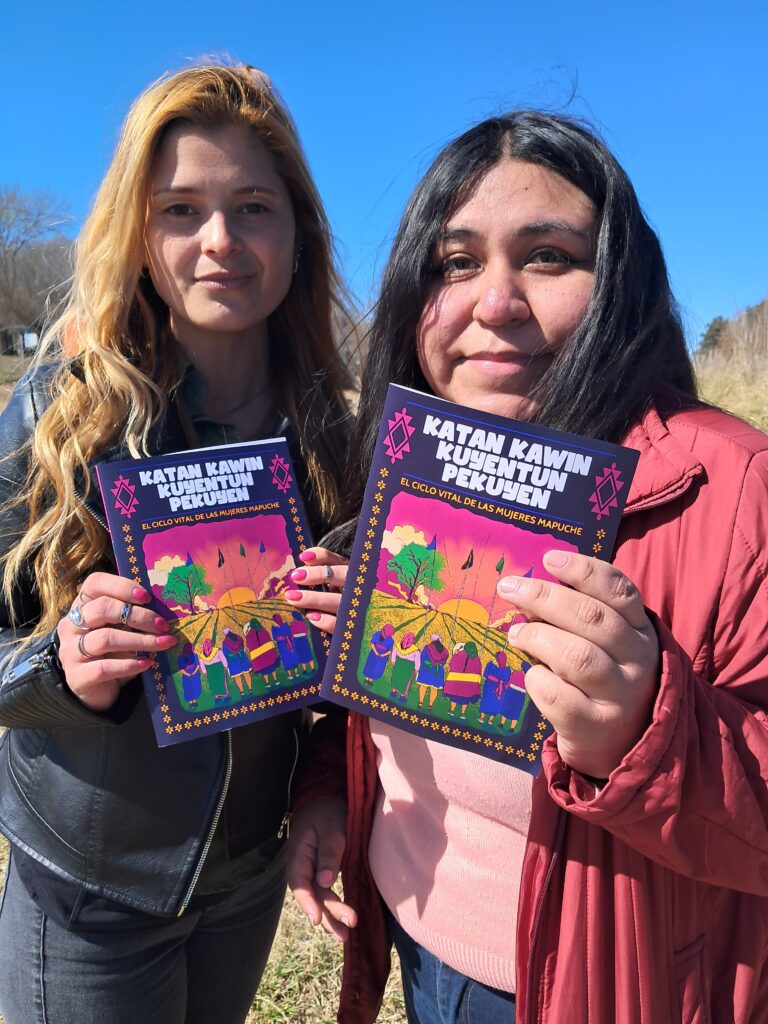

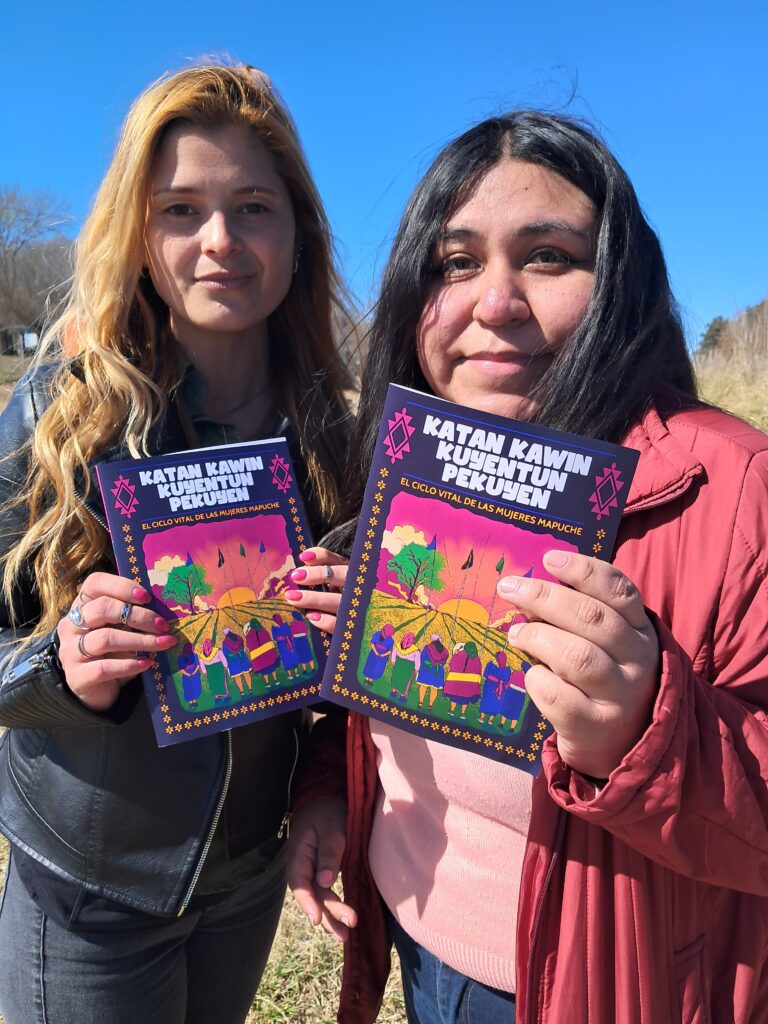

“Katan kawin kuyentun pekuyen. The life cycle of Mapuche women” is a collective work on sexuality and ancestral practices that are being rescued today.

Share

The first menstruation, the pleasure of sexual relations, the decision to conceive or not, menopause. Different moments in the life cycle that are hidden, disguised, whispered about, spoken of with shame, with ellipses. “I got my period,” “I got my period,” “I have hot flashes.” While in many cultures there are topics that seem to be exclusive to the intimate and private sphere, the Mapuche worldview maintains that what happens to us in our bodies also happens in the territory . Thus, the individual is assumed communally as a public and collective matter.

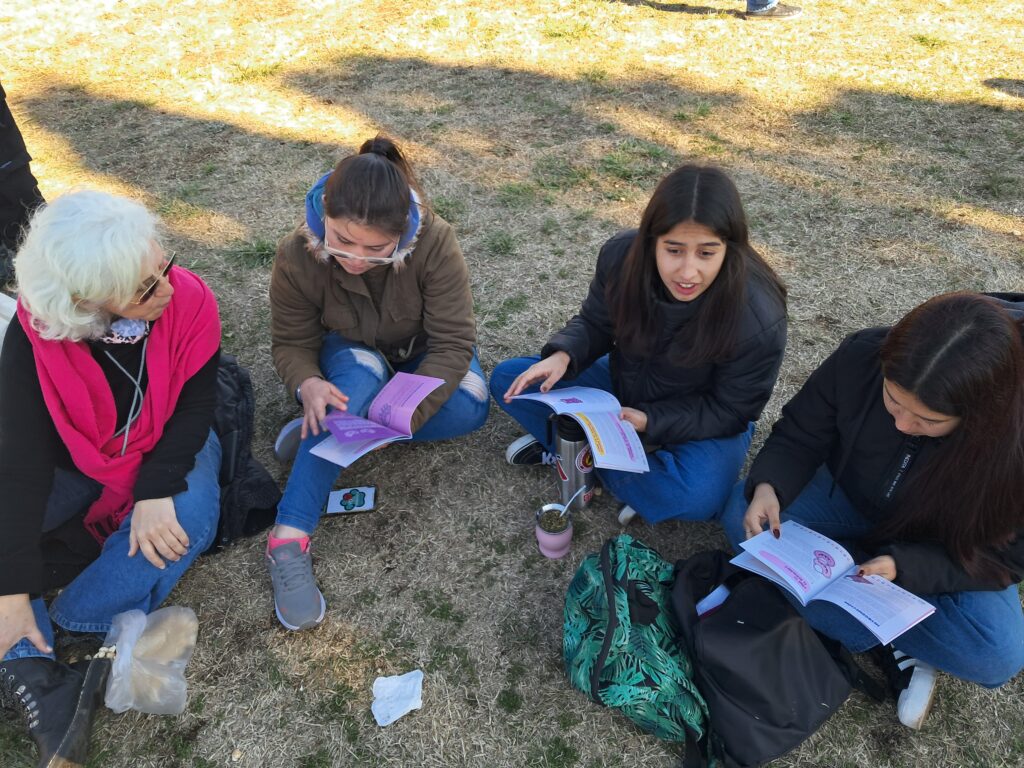

All these reflections and debates took place at the “First Day of Comprehensive Sexual Education with Mapuche Identity” organized by the Mapuche Community Epu Lafken of Los Toldos, in the northwest of the province of Buenos Aires, within the framework of the International Day of Indigenous Women .

Students from various high schools and the nursing program participated in a large bicycle ride to Casa Azul, the rural headquarters of the Mapuche community. There, they presented the booklet “ Katan kawin kuyentun pekuyen . The Life Cycle of Mapuche Women .” It is a collaborative work written by Mapuche political scientist Verónica Azpiroz Cleñan with the guidance of pillan kushe (spiritual guide) María Elena Tripailaf from the Lanín volcano in Neuquén.

Neither virginity nor monogamy

The material recovers ancestral knowledge, dismantles taboos, and challenges the impositions of Christian beliefs that associated the female body with sin. It analyzes the horror and/or fascination with which various Spanish authors documented the sexual freedom of Mapuche women during the colonial era.

For example, the booklet emphasizes that virginity held no weight when forming a couple. It even recounts that a pregnancy prior to marriage was not a cause for conflict. If "the newlywed is already pregnant by another man, then the husband almost always decides to adopt the unborn child," they said.

They also explored the theoretical work of several lamngen (sisters) who researched sexuality and pleasure, and identified what could now be defined as a sex toy specific to Mapuche culture. The weskel was a type of cloth made of horsehair that was tied to the penis to stimulate the clitoris and induce orgasms. “This means that sexual pleasure was not hidden or concealed, but rather that there were instruments to enhance women's enjoyment.”

It can be observed that the consequences of the genocide extended to sexuality and relationships: polygamous affective structures were abruptly transformed by the conquest. The booklet notes that both longkos (community political authorities) and weychafe (warriors) engaged in polygamous practices, as described by historians of the time. And while they mention polyandry, the state of a woman in a simultaneous affective relationship with two or more people, they acknowledge that it is the least historically documented practice. “Polygamy or polyandry gradually died out or was hidden due to the Catholic moralistic prejudice that overvalues monogamy,” they maintain.

Without territory, enjoyment becomes a distant prospect

What is happening today regarding the sexual freedom of Mapuche women? “Mapuche sexuality and pleasure is not a topic that is being discussed publicly in community spaces,” responds Verónica Azpiroz Cleñán, adding: “Disputes over territory, violent evictions, and the criminalization of indigenous identities make enjoyment a very distant reality.”.

For the Mapuche political scientist and doctoral candidate in public health, today “the priority is survival. Surviving if you don't have water, surviving if it snows, surviving if they come to fumigate, surviving if they try to evict you, surviving if they file criminal charges against you. There is a fragility of the rule of law in Argentina that means that issues strictly related to sexual health and pleasure, and the way the body is perceived, are relegated to the background. Even though women, especially women, are bringing these issues to the forefront.”.

“ Katan kawin kuyentun pekuyen. The Life Cycle of Mapuche Women” is precisely one of the forms of advocacy, a resource created collectively with the drive of Mapuche women from the province of Buenos Aires, which was self-published and is already circulating in schools in Los Toldos. In addition, a series of five videos in which Mapuche women from different territories narrate their experiences in the first person; these materials were produced with the support of the Southern Women's Fund (FMS) and the Indigenous Professionals Network.

White feminism and a purely discursive intersectionality

For many years, Indigenous, Afro-descendant, grassroots, and migrant feminist and anti-patriarchal movements have been criticizing "white" or hegemonic feminism, which they accuse of perpetuating a racist, Eurocentric, and classist logic. The discussion centers on the idea of intersectionality : gender oppressions are not separate from those of class and ethnicity.

However, according to the author of the material, “intersectionality is a concept used within academia, but it doesn't translate concretely into public policy.” In that sense, Azpiroz Cleñan proposes an exercise: “If you look at the working groups of feminist organizations, there isn't a single Black or Indigenous woman on the main staff. So there's a discourse, but there's no real implementation of that intersection.”.

The booklet values the Comprehensive Sexual Education Law 26.150 but points out that “there are no materials produced by the state apparatus from our Mapuche worldview on sexualities. A lot of discourse on intersectionality and little concrete action.”.

The Mapuche political scientist asserts that “feminism never addresses linguistic rights in its daily practice, and even less so does the State enforce these rights in access to healthcare. No one asks, for example, how to address the inequality in access to public health services when a woman is monolingual in Wichí, Qom, or Pilagá.”.

The material argues that the imposition of Christianity forced the concealment of menstruation, desire, pleasure, and the enjoyment of the body. “For this very reason, we are committed to reversing coloniality (even within white feminism) and bringing to light our cultural ways of experiencing bodies, words, advice, clothing, and joy, and sharing them so that the processes of re-Mapucheization multiply,” they say.

The menarche festival

The Epu Lafken Mapuche Community set out to recover various Indigenous practices that were suppressed by the genocide upon which this country was built. Ceremonies are key because they provide a common space for women who have managed to preserve the language to share Mapuche kimün : Mapuche knowledge that encapsulates the language and its memories. One of the rituals that had been lost and is now being revived is Katan Kawin , the women's fertility festival.

The material explains that “the celebration of menarche (first menstruation) is experienced communally because what is celebrated, at the same time, is the fertility of the land, the possibility of fertilizing new seeds, of generating food, of nourishing other lives. Human life is associated with the life of the territory, which is why the fertility festival belongs to the entire land.”.

María Elena Tripailaf, a traditional Mapuche authority, explains that in the Katan Kawin “the adolescent is prepared for life. We call her maiden. The chaway (silver earrings) are placed on her, and she is given ngülam (advice) so that she has clarity on her path and knows the values she has as a Mapuche woman.”

It's a joyful celebration. Adult women bring flowers, gifts, and silverware. They share all sorts of advice, including tips for healthy sexuality. "The women have the task of preparing this young woman and giving her advice and gifts she can use for protection throughout her life," says the pillan kushe (spiritual guide) of the Mapuche people.

And what about the men of the Epu Lafken Community regarding the revival of this ceremonial rite? “They are happy,” says Azpiroz Cleñan, “because they are the fathers of the girls who have had their first period. For two years we have been supporting this process, trying not only to revive the Katan Kawin , but also to support the daughters’ friends, to give them other tools that will sustain and strengthen them.”

Plenopause and political leadership

To talk about menopause, the Epu Lafken Community joins various feminist spaces that rename the end of the menstrual period as "plenopause": a perspective that encourages thinking of this life cycle as a moment of fullness.

“In this phase we have more time for community or collective activities, to transmit knowledge, experiences and to live sexuality focusing on pleasure, on relaxing non-reproductive sexual health care. Many of us have more time to lead political processes,” they say.

Furthermore, they warn that this is a time in life where the hegemonic medical system proposes medicalization with hormonal supplements with prescriptions that they consider "not universal nor have arisen from the specific needs of Mapuche or indigenous women on this continent.".

The booklet lists some precautions to take “when the moon comes” (menstruation) and reviews the use of various plants to alleviate pain, mood swings, or increase sexual desire during peküyen (menopause/plenopause). These are tips, experiences, and reflections that were silenced for years but remained in collective memory and today, thanks to the work of many Mapuche women, are resurfacing in their territories.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.