Why is September 5th International Day of Indigenous Women?

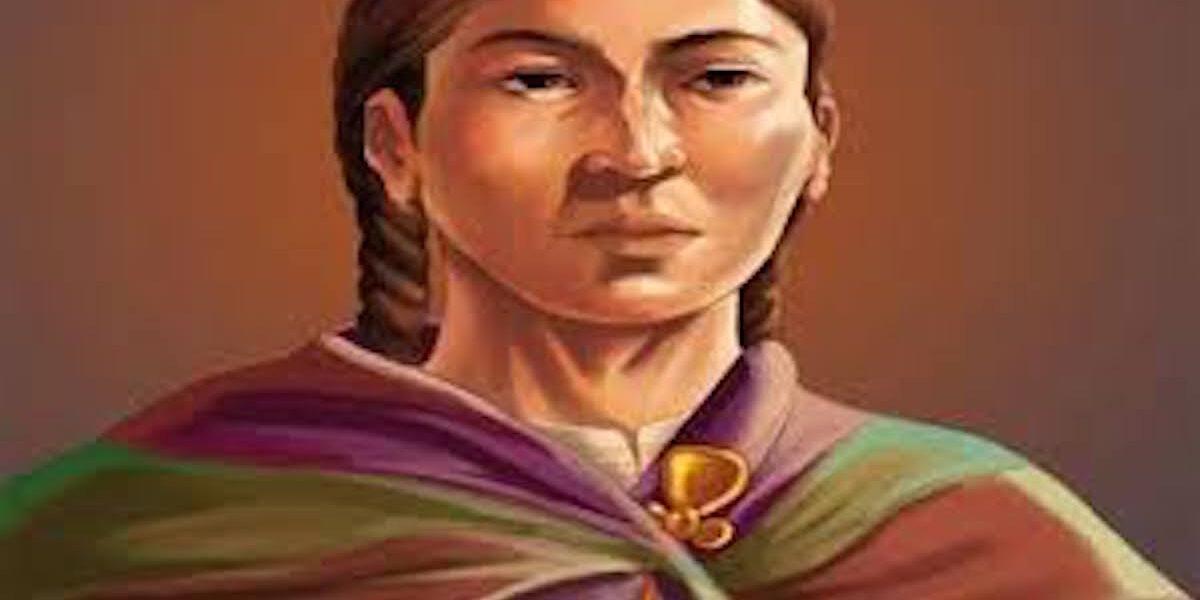

September 5th is commemorated as Indigenous Women's Day in honor of Bartolina Sisa, an Aymara woman who fought against the Spanish empire.

Share

September 5th is commemorated as Indigenous Women's Day in honor of Bartolina Sisa, an Aymara woman who fought against the Spanish Empire and was tried in 1782 and subjected to a cruel public execution. The date was established at the Second Meeting of Organizations for the Legitimate Rights of Indigenous Nations to remember one of the great indigenous uprisings against Spanish exploitation.

On the nights of March 1781, the hilltops surrounding La Paz were illuminated by bonfires, and the loud, hoarse sound of the "potutos"—ox horn trumpets—of the Aymara troops filled the air. On March 13 of that year began what would become the most significant military event among the indigenous uprisings of the late 18th century against Spanish colonialism: the siege of La Paz, led by Bartolina Sisa and Tupac Katari.

The awakening to the struggle

With a childhood steeped in trade, Bartolina Sisa, along with her family, was able to escape the servitude imposed on the indigenous population by feudal lords. Furthermore, through the numerous journeys her family made transporting coca and textiles, Bartolina witnessed the subjugation and harassment endured by many indigenous people in the Yungas, Sicasica, and La Paz regions. In 1769, at the age of 19, Sisa established her own trading company and became independent from her parents.

A similar fate befell Julián Apaza, whose nom de guerre was Tupac Katari. Born in Ayoayo and orphaned at a young age, the young man was soon called to serve in his village church and lived for a few years in the rectory. This allowed him to witness the exploitation of the farmworkers and the plundering of their meager produce. At 17, he was drafted into the mita labor system for the mines of Oruro, where he remained for two years. There he witnessed the "inhumane treatment meted out by overseers, stewards, and soldiers, with whips, beatings, and arquebuses," as described by Alipio Valencia Vega in his book Bartolina Sisa (1978). Upon returning to his community, he learned of the burgeoning trade in coca and local textiles and decided to enter the business himself.

Sharing a common purpose, Sisa and Apaza met at one of the way stations along the trade route and married in 1770. During their trading journeys, the couple came into contact from the early 1770s with Gabriel Condarkanki ( Tupac Amaru ), a descendant of the Incas born in Tinta; his wife, Micaela Bastidas Puyucahua ; and Tomás Katari and his brothers, from Chayanta. In this way, ten years in advance, they began planning the indigenous uprisings of 1780 and 1781 against Spanish rule, beginning in Chayanta, followed by Tinta, and finally, the siege of La Paz.

Women in the Aymara uprisings

The 'Other' Women of the Sisa-Katarist Rebellion (1781-1782)," journalist Mariana Ari women were not only commanders, generals, and soldiers but also creators of ideology, both through their actions and discourse ." While this surprised the Spanish, women's participation in the insurrection was consistent with the foundations of the pre-colonial indigenous family, where men and women were equal in working the land.

In the Aymara uprisings of the early 1780s, Bartolina Sisa commanded and secured the obedience of her troops alongside her husband, Tupac Katari. She was appointed viceroy of the Inca and contributed ideas and advice to the development of the insurrection. When La Paz was besieged in March 1781, to avoid neglecting the two main camps, Katari took charge of El Alto and Sisa of Pamjasi, in a complementary fashion.

Although the Spanish possessed firearms and superior warfare technology, the troops of Katari and Sisa inspired fear not only because they numbered up to 80,000 fighters, but also because of their remarkable offensive. For this reason, the royalist army resorted to inciting treason within the indigenous ranks. Thus, Bartolina Sisa was captured on July 2, 1781.

In prison, the Spanish tried to get Sisa to confess, but instead received one of her most famous statements. When they questioned her about her motivations for the rebellion, she replied: “So that with the white face extinguished, only the Indians would reign.”

On November 10, 1781, Tupac Katari was surprised and captured by Captain Mariano Ibáñez of the Savoy Infantry, the result of yet another betrayal within his own ranks. Two days later, he was sentenced to a brutal death in the Plaza de Peñas. This news reached Bartolina Sisa, and her own death sentence was pronounced a year later, on September 5, 1782, by Judge Francisco Tadeo Díez de Medina.

“When the Spanish invaders realized that Indigenous women were fighting alongside their male counterparts on equal terms ,” writes journalist Mariana Ari , “ the violence against them intensified in ‘exemplary’ exterminations carried out in the communities.” The execution of Bartolina Sisa was one of these. In his notebook, Díez de Medina detailed the sentence: “Her head and hands shall be impaled on stakes with the corresponding inscription, and displayed as a public warning in the places of Cruz Pata, Alto de San Pedro, and Pampajasi, where she was encamped and presided over her seditious meetings.”

In 1983, at the Second Meeting of Organizations and Movements of the Americas, it was decided that September 5th would be celebrated as the International Day of Indigenous Women in their honor . Bartolina Sisa was perhaps the most celebrated name among the women who fought in the indigenous uprisings, but she was certainly not the only one. Other prominent figures include Tomasa Titu Condemayta, Micaela Bastidas Puyucagua , Manuela Condori , Gregoria Apaza , and many other renowned heroines, as well as countless others who remain anonymous. September 5th commemorates them and invites us to reflect on the current situation of indigenous women worldwide.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.