The trial begins for the femicide of indigenous woman Nancy Fernández

The woman was murdered in 2014, a year after her 14-year-old daughter Micaela was found dead, while demanding justice and denouncing trafficking networks in the Buenos Aires municipality of Tigre.

Share

The trial for the "indigenous femicide" of Nancy Fernández, a member of the Qom Yecthakay community, begins today before the Oral Criminal Court No. 7 of San Isidro. Fernández was murdered in 2014, a year after her 14-year-old daughter, Micaela, was found dead while demanding justice and denouncing human trafficking networks in the Buenos Aires municipality of Tigre.

Judge María Cohelo and Judges Marcelo Gaig and Alejandro Lago, of the 7th Oral Criminal Court of San Isidro , will preside over the trial of Juan Carlos Corvalán, the sole defendant. Corvalán was a fugitive until his capture last June. He faces charges of aggravated homicide due to the familial relationship and the presence of gender-based violence (femicide), as well as theft.

The trial will run from September 3rd to 6th. Hearings will begin at 10:00 AM at the courthouse, located at 460 Centenario Avenue. Indigenous, feminist, social, and political organizations, along with family members of victims of femicide, transfemicide, and human trafficking from the northern suburbs of Greater Buenos Aires, such as the families of Luna Ortiz, Viviana Altamirano, and Sofía Fernández ,

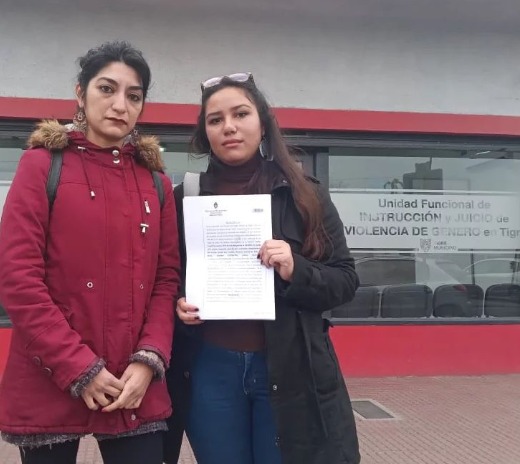

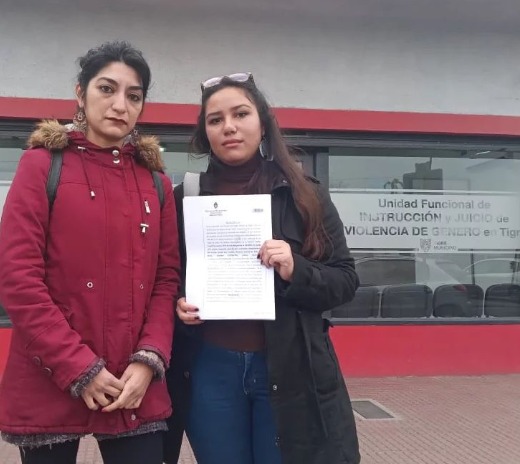

“For what I have been fighting for so long, and for what my grandfather and my mother fought for, I hope for justice,” Lisette Fernández, 23, daughter and sister of Nancy and Micaela, told Presentes as she prepared to go to the first hearing.

“ I’m very afraid because I know how the justice system works. I’m afraid of being mistreated, of being revictimized, of people speaking ill of my sister or my mother, of reliving things. It’s hard for me to talk about it, to see photos of them. These things break you. It’s very difficult to go on after so much,” she shared. Following the events she experienced, Lisette was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. People close to her manage the Instagram account @la_loz_de_mica, where they share updates on both cases.

In February 2013, Micaela Fernández, Nancy's daughter, was found dead with a gunshot wound to the head at Dante "Pato" Cenizo's house. "The last time I saw Mica was for my birthday; I was turning 12. We had a lovely day together, and then late in the evening, a car came to pick her up. That's when she said she had to leave. I asked her to stay a little longer. She told me she would be back during the week. I never saw her again," Lisette told Presentes .

The tests

For her and her lawyer, Paula Alvarado Mamani, both cases—Micaela's, classified as "suicide," and her mother's, classified as "homicide"—should be consolidated. "There is ample evidence," she believes, "to establish that both deaths were murders linked to a human trafficking network.".

“My sister was kidnapped in 2013. I heard from her that he (Dante Cenizo) was prostituting her, that he was forcing her to sell drugs. I saw my mother beaten when she went to report the kidnapping. They locked her up and beat her. I also witnessed the injustice, the complicity of the police. Out of fear that something would happen to me, my mother sent me to live with an aunt,” Lisette recounted.

When Micaela disappeared in 2013, her mother, Nancy, went to the Sixth Police Station in El Talar to report her disappearance. They treated her like she was "crazy" and refused to take her report, Lisette recalled. Days later, Micaela reappeared, beaten, with injuries to her face, her hair brutally cut. She said she had been taken to a house where she was abused by several men. At that point, Nancy again tried to file a report, but ended up being arrested. In February of that year, Micaela was found dead in Cenizo's house. A year after her death, on May 2, 2014, Nancy was found dead in her own home. A homicide case was opened to investigate this crime, and it has now gone to trial.

Nancy's father, Eugenio Fernández, founder of the Qom Yecthakay community in Tigre, spearheaded the fight for justice for the deaths of Nancy and Micaela. “Sometimes we are abandoned because, being Indigenous, it's as if we are second-class citizens. I want this to come to light and for those responsible to be arrested,” Eugenio had stated during an interview . After his death, Lisette took up his mantle and, upon reaching adulthood, gained access to the case files.

To talk about what happened to her mother and sister, Lisette uses the term “Indigenous femicide” because she believes it is also linked to racism. “We are more vulnerable. The traffickers know who they target: the most vulnerable girls. They know that when we go to ask for justice, they don't listen to us, they discriminate against us,” she explained. She knows this, among other things, from her mother's experience. “'Shut your mouth, you fucking Indian,' they told me. 'You're not going to talk,'” Nancy recounted in an interview with Public TV . She also publicly denounced police abuse when she went to file a report.

“All I hope for is justice. I know it doesn’t end here because I know they want to close my mother’s case as if it were isolated from my sister’s, and that’s not the case. They are ignoring the entire context in which my mother’s murder occurred, a context of human trafficking, drug trafficking, and racism,” Lisette concluded.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.